Exclusively with A Rabbit’s Foot, the shapeshifting artist discusses her latest trilogy of Halloween films.

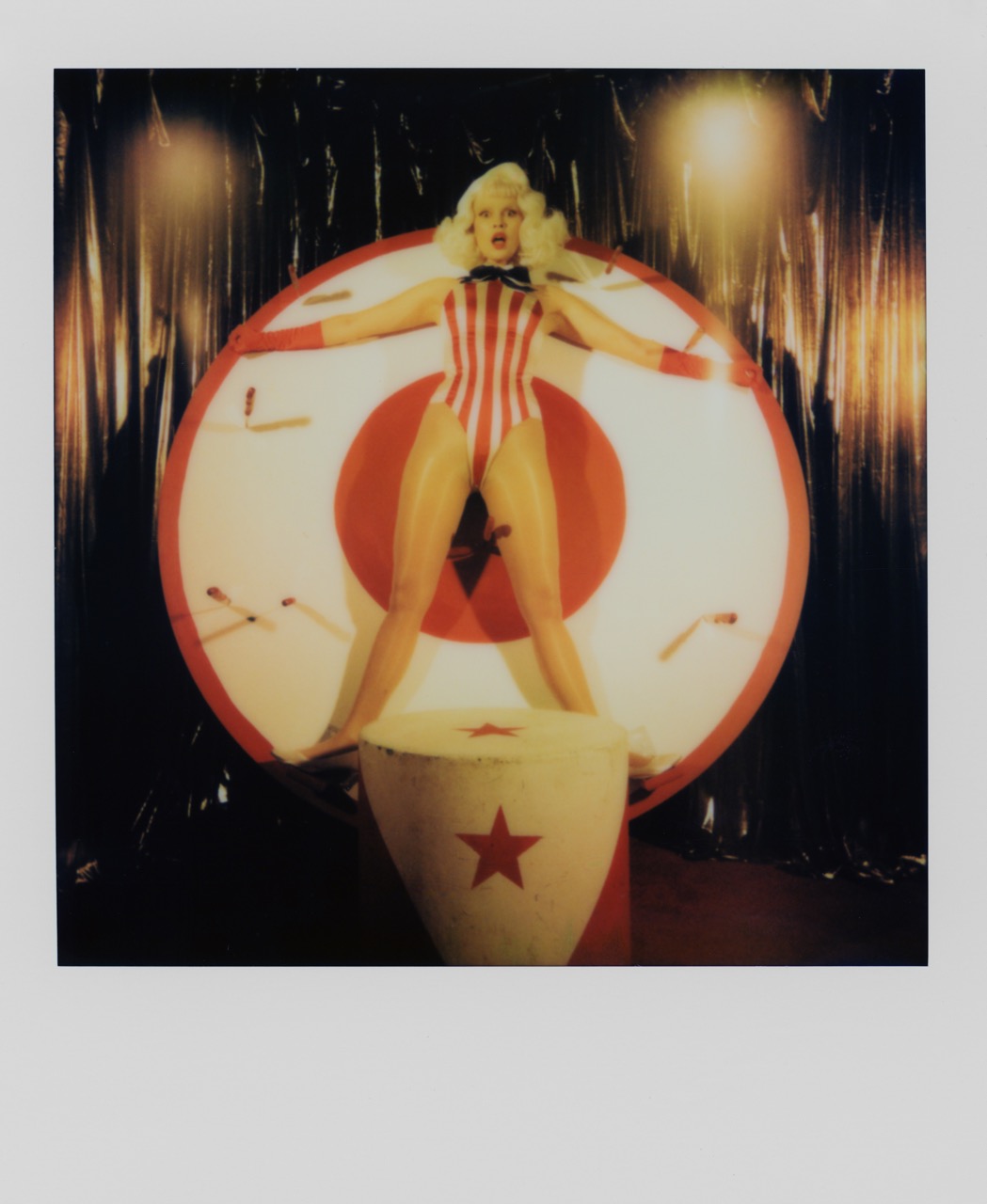

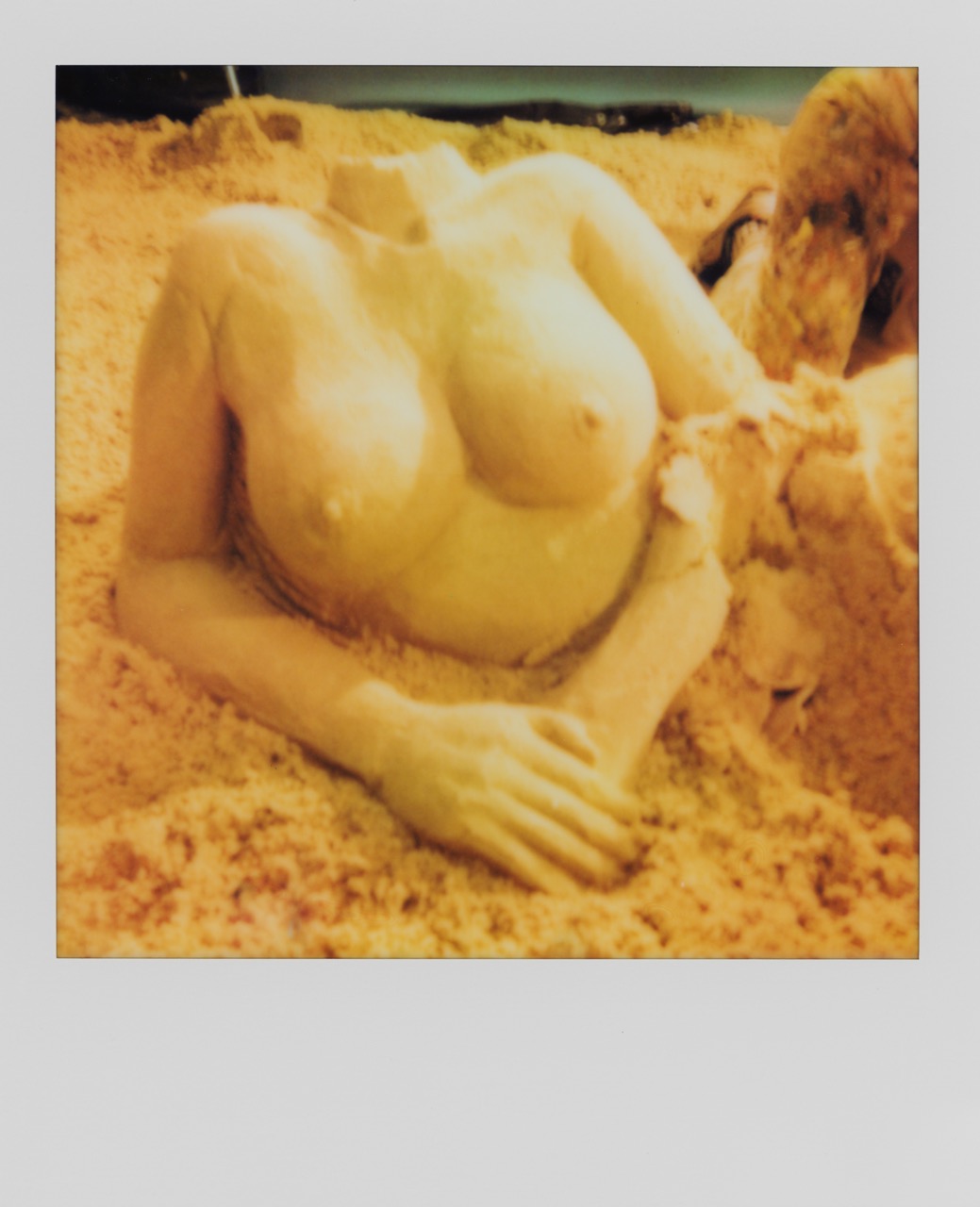

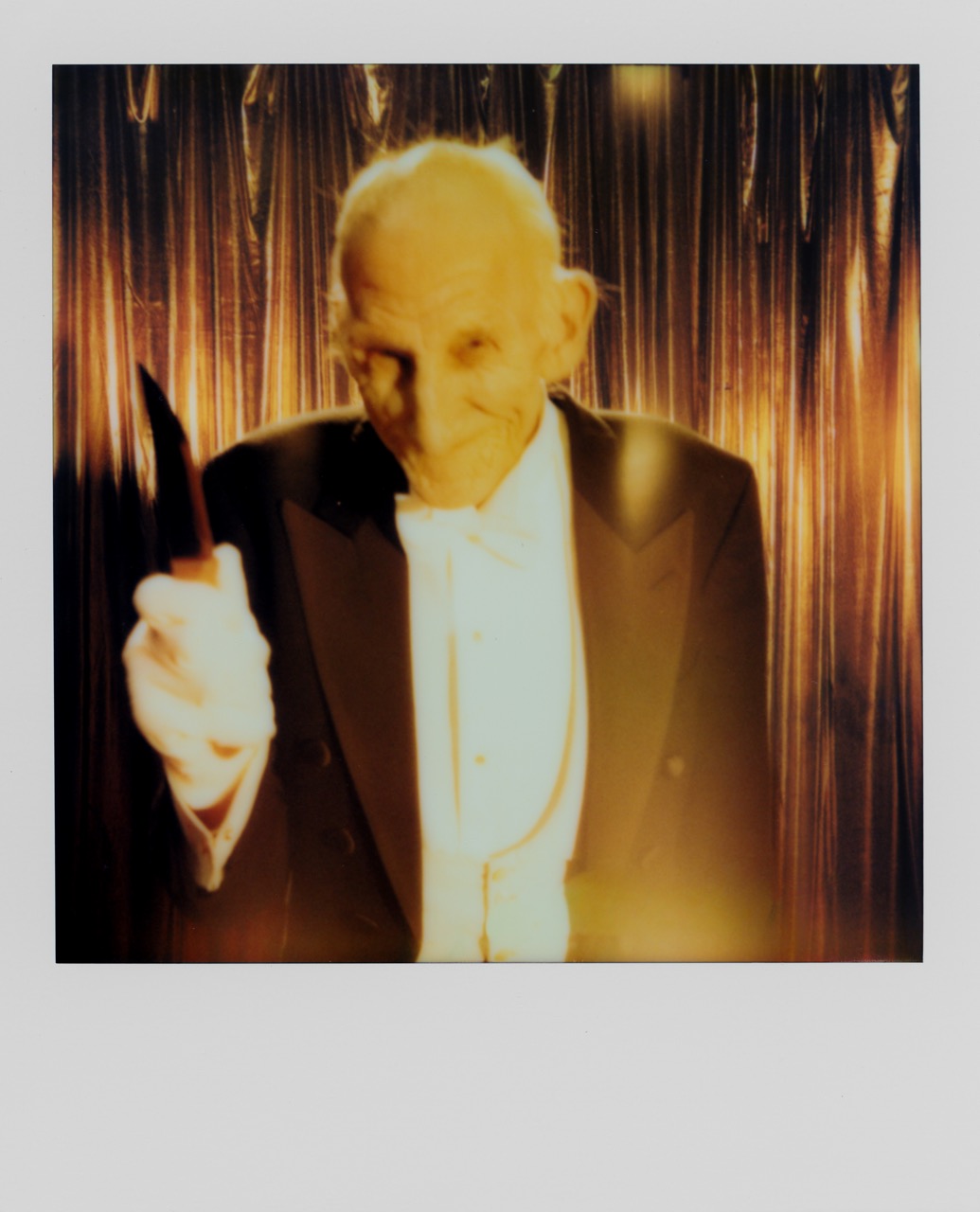

A living female nude, made from sand. A magician’s assistant pinned up on a wheel, having knives thrown towards her (a splash of blood landing on a nearby bunny rabbit). An actress in a screen test, who, scrutinized by male studio heads, slowly turns into a fly. These three vignettes describe a trilogy of new short films from Frances O’Sullivan, who, as is quickly becoming a Halloween tradition for the artist, has once again launched a series of special works in honour of spooky season.

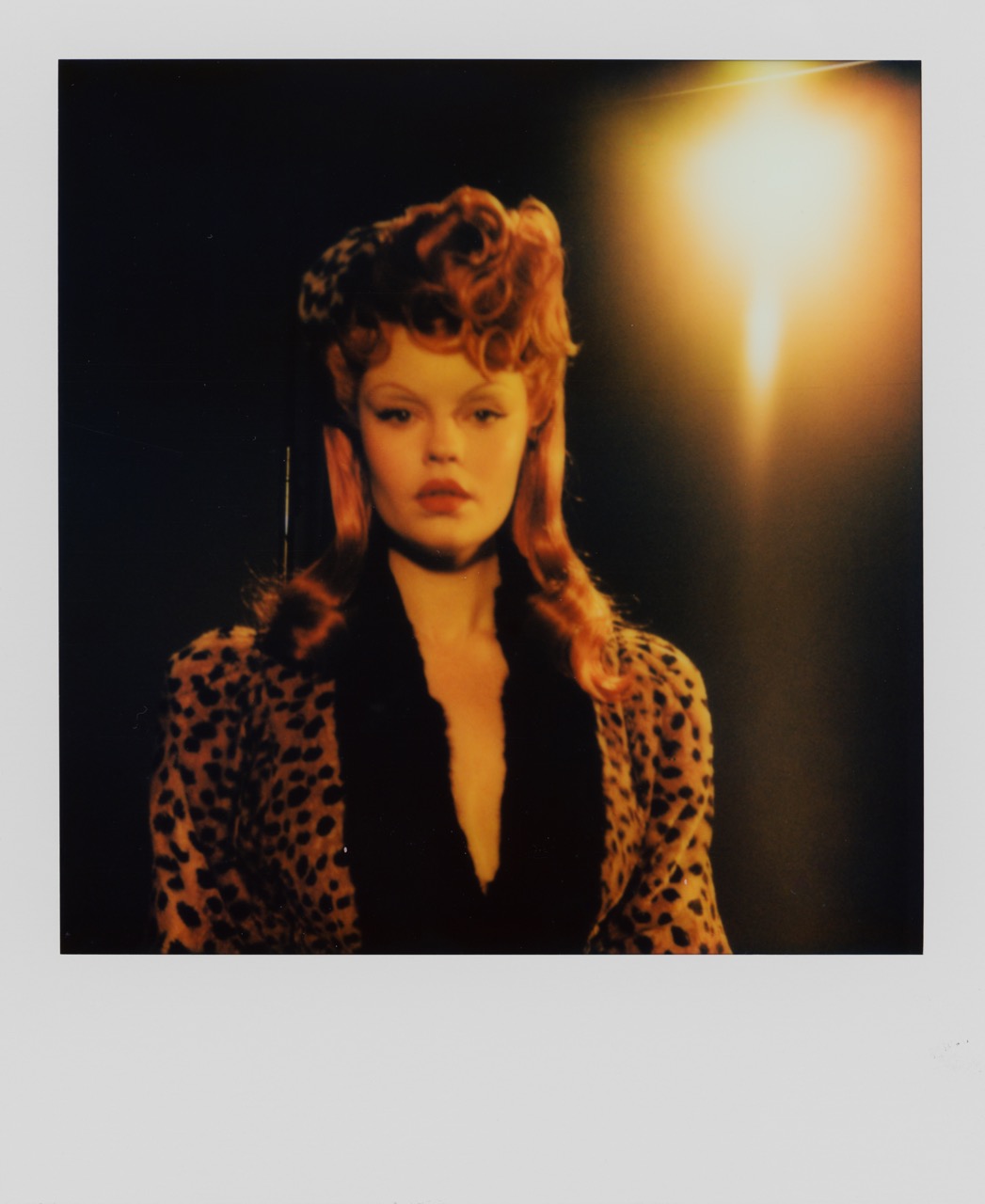

Known for her transformative self-portraiture (you may recognize her from the Instagram account @beautyspock), O’Sullivan’s films blur the lines between glamour and grotesque, creating vivid, stylised worlds that, whilst evidencing a truly cinephilic sensibility—with references from David Cronenberg and David Lynch to 1940s and 50s movies—emerge as something of their own entirely. “Screen Test felt like the result of the The Red Shoes and The Fly going through the telepod together and emerging as a mutation of the two,” says O’Sullivan.

Below, O’Sullivan speaks with A Rabbit’s Foot about her inspirations for this year’s films.

How did you come up with the three stories in this year’s trio of Halloween films? Can you tell us a little about them and how they sit together? What did you want to explore which you haven’t in previous years?

Each year’s project seems to spill out as a reflection of whatever’s been rattling around in my brain whether that be films, books, people, paintings, and the odd personal experience that’s left its mark. Usually, I like each film in the series to live within its own individual world and genre, but this time I wanted more connective tissue. I wanted to explore more of a narrative whereas in the past the absence of narrative had been the entire point.

What were the inspirations—or what was on your moodboard when putting these together?

Earlier this year, I fell down a bit of a rabbit hole with late 1940s to early ’50s cinema that all have those gloriously artificial, hand built sets. From the scenery, staging, colour palette and aspect ratio, these were all on my mind while creating the concepts. In terms of specific inspirations for this year’s films, Screen Test felt like the result of the The Red Shoes and The Fly going through the telepod together and emerging as a mutation of the two.

Across both this annual series and my work as a whole, the queer artistry of the film and entertainment world over the 20th century has been a permanent undercurrent of inspiration and a foundation we all build upon, often without realising it. Without that lineage, we wouldn’t have the same language or tools to make art the way we do. Leigh Bowery, Divine, Grace Jones, Amanda Lepore, John Waters, David Bowie just to name a few all played a part in re-wiring how I understand performance, identity, and the act of turning the self into art.

These are hyper-short short films that have a high production value—what are the attractions, but also challenges of this form as an artist and filmmaker?

The kind of film and photography I’m drawn to usually demands a high level of production, which in the past has meant having to learn how to create big worlds with whatever resources are at hand. The eras I love to work within are tricky to recreate without certain essentials, one being hair, which is the centre of gravity in almost every project I do and the unsung hero of my work. Early in my career, I met my good friend and “hairy godmother,” Sarah Wood, a master of wigs and styling, who I have worked with ever since and has adorned the head of every character I’ve gone on to make. In tackling the challenges of this year’s series, I had the pleasure of working with some incredible creatives including our amazing sand sculptor, Nicola Wood, who spent 5+ hours constructing an exact replica of my body out of 2 tonnes of sand. Working with a team like this not only makes it physically possible but is one of the most enjoyable elements.

All the films explore objectification in some way, and the third film in particular is a satire of the misogynistic cinema industry—do you see horror as a way to subvert the male gaze?

Absolutely. Art has long catered to men as an outlet for their fantasies, particularly in the horror genre. It gives the freedom to distort and exaggerate reality without restraint which is often misused. However, I’ve found the same tools can reclaim power through provocative parody.

The tension between attraction and revulsion is where the real appeal of horror lives for me. When my body of sand crumbles in half, is it disturbing or arousing to people? I imagine probably both.

Frances O'Sullivan

There is such a merging of the grotesque and visual pleasure in your work—how do you think about the aesthetics of horror?

I’ve always thought our fascination with the macabre and beauty run in parallel. As animals, we’re naturally drawn to and somewhat seduced by both in morbid curiosity, even when it makes us uncomfortable. David Cronenberg has been a huge influence on how I see this brought to film with the way he weaves sexual desire and body horror together. That tension between attraction and revulsion is where the real appeal of horror lives for me. When my body of sand crumbles in half, is it disturbing or arousing to people? I imagine probably both.

Has horror always been a genre you have been drawn to—what was the earliest horror film you remember seeing and made an impact on you?

As a kid, I was obsessed with the idea of horror more than the actual films themselves, purely due to the fact that I was too young to watch them. I remember going into the horror section at Blockbuster to look at the covers before I was allowed to rent them out and then drawing them at home. One night I snuck downstairs to watch a late night showing of The Exorcist on TV when I was far too young, and that was that. It made me feel sick and I loved it. Later on, learning about the mechanics behind it all: the practical effects and craftsmanship made me love it even more. It’s a genre that’s historically underfunded and overlooked by critics yet built on creativity and resourcefulness.

You are the star of these films—are you your own muse? And how was the process of casting other actors? The old magician is amazing.

Using myself in my work really started out of pure convenience. In the early days, I was creating characters and scenes for them to inhabit but didn’t have the budget to hire models or actors, so I just threw myself in front of the camera. Over time, it has formed more of a significance after having grown a fascination with the craft of self portraiture. However, for this project, I cast myself pretty quickly, then got to set and thought, shit, now I have to act. Casting the rest of the project was much more fun. For the magician, the criteria was that he should resemble a hybrid of Lurch and the Giant from Twin Peaks and he did, spectacularly.

What has been your greatest Halloween outfit of all time—and more importantly, who will you be going as this year?

For me, the first half of October is for the polished looks, the 31st is for whatever I can cobble together an hour before leaving the house. One of my favourite past efforts was a mermaid for which I was sealed into a 20-kilogram silicone tail after being slathered in conditioner while laying in a bathtub. A truly horrific experience, and therefore perfectly seasonal. This year’s costume will, as usual, be a last minute decision, but whatever it is, I’m certain I’ll have the wig for it somewhere.