Since becoming friends in the 1980s, John Malkovich has played a Scarlet Pimpernel-like presence in Natasha A Fraser’s life. To quote Baroness Orczy’s 1905 novel, “They seek him here. They seek him there. Those Frenchies seek him everywhere.”

PARIS—Imagine wearing a pink 18th-century wig when interviewing John Malkovich. “It looks great,” the American actor assures me, followed by a signature feline smile. I can explain. Malkovich is in Santiago, Chile, filming Wild Horse Nine for the Irish director Martin McDonagh. But due to the time difference, we need to Zoom before I delve into the French countryside for a 50th birthday party.

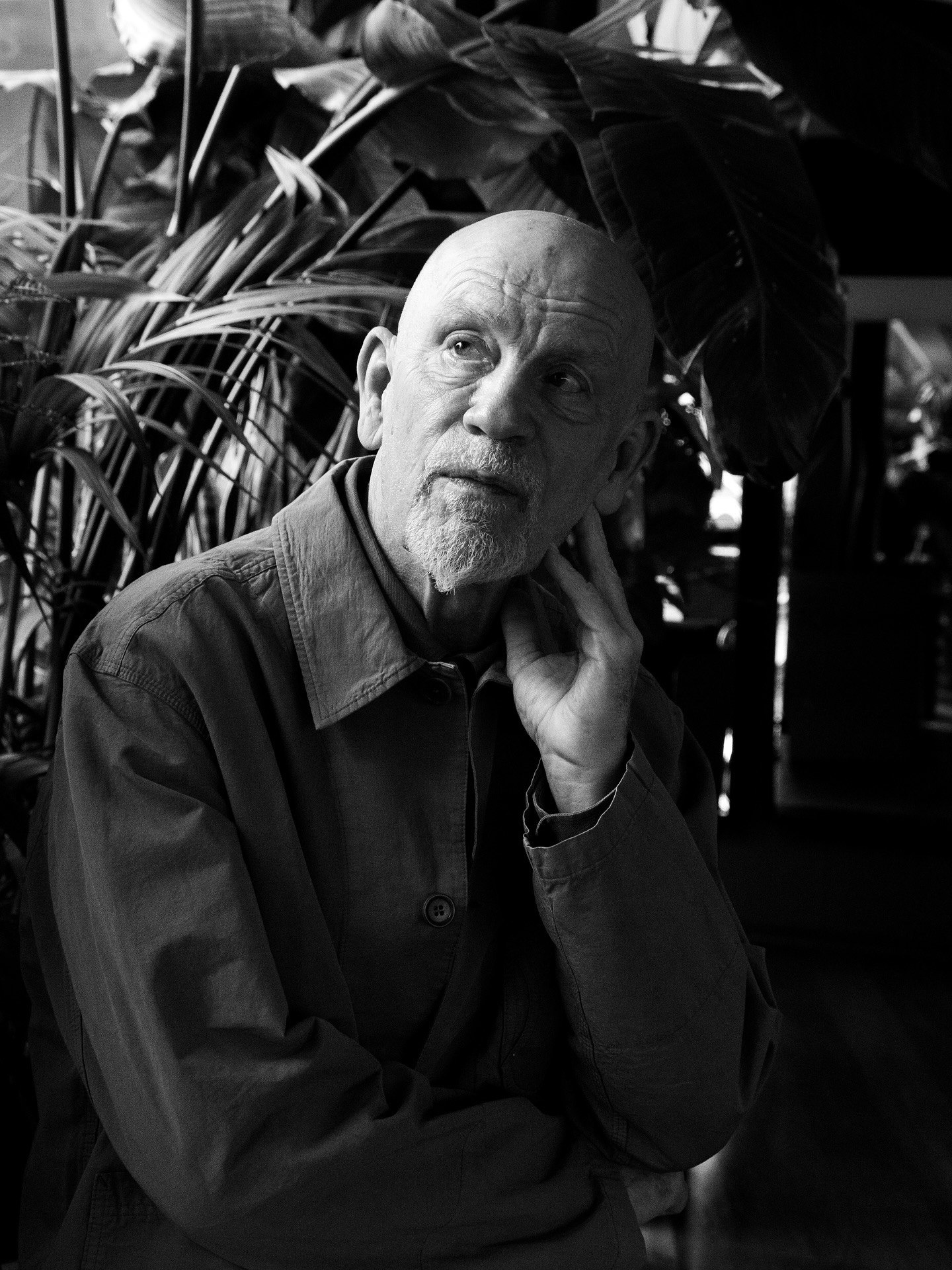

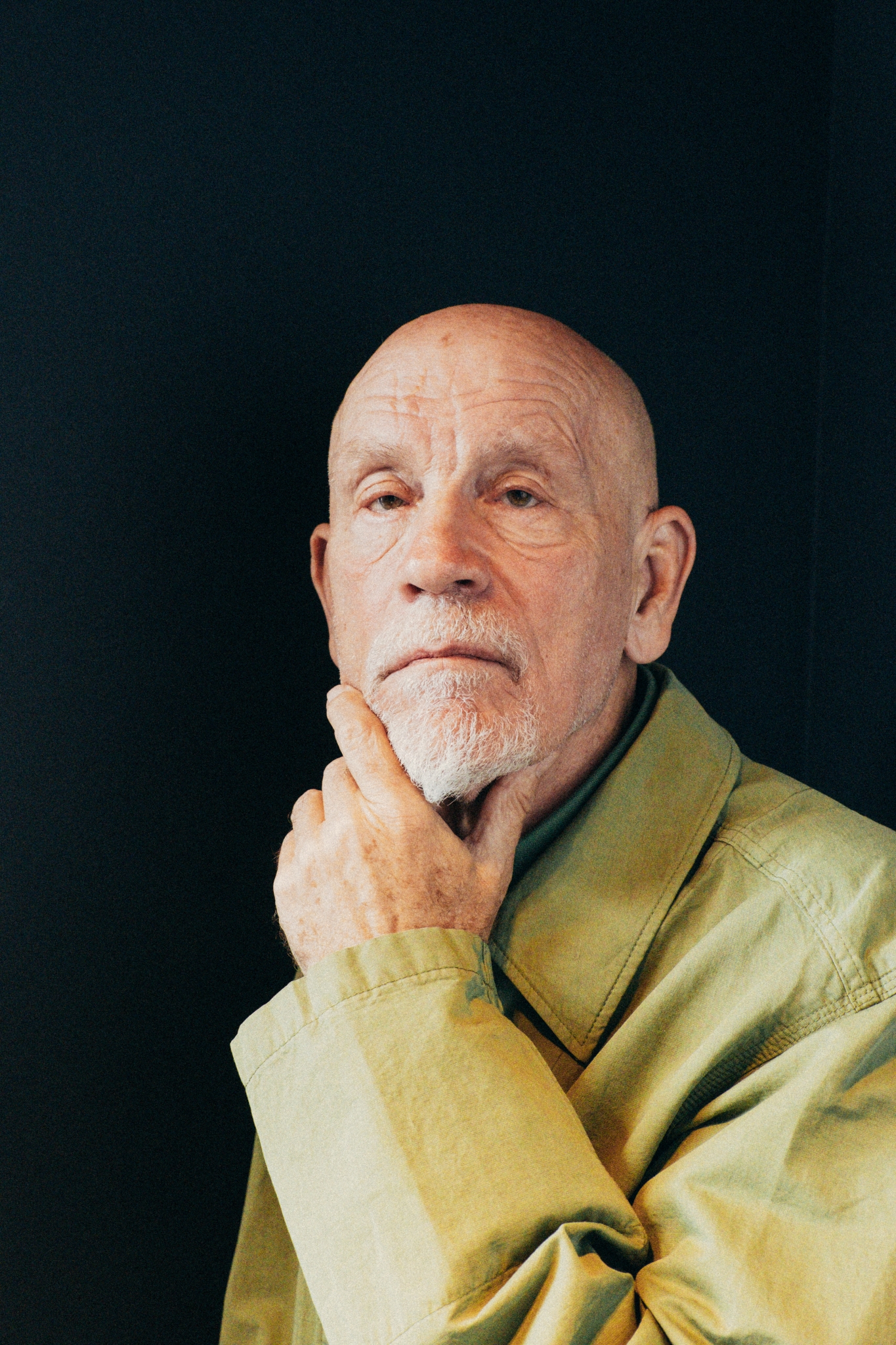

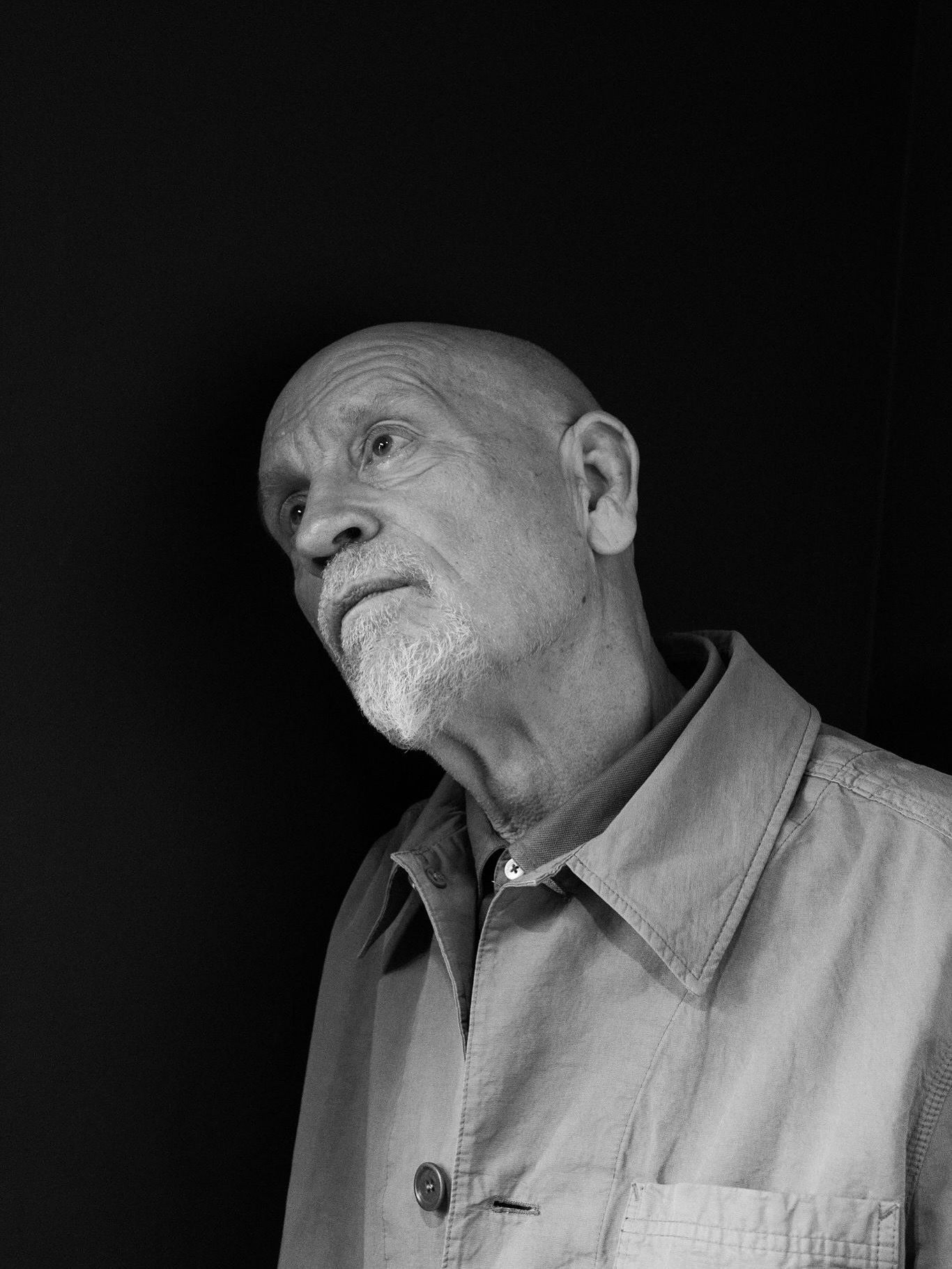

Thankfully, Malkovich’s response to my question makes me forget my itchy wig. I wrongly assume that he would have taken a childhood trip to France, like most midwest Americans. “No, we were five children in the family and never went anywhere,” he replies. “We were all pretty feral. I doubt we would have been allowed into another country. Or perhaps if allowed in, not allowed out.” It’s hard not to laugh. I’ve known Malkovich since 1987, and he is a performer whose humour and imagination have allowed him to seamlessly range from a chillingly droll convict (Con Air, 1997) to a camp sendup of himself (Being John Malkovich 1999) to royal usurper (Johnny English, 2003) to cuckolded CIA analyst (Burn After Reading, 2008) to perverse pontiff (The New Pope, 2020) to a vindictive pop star (Opus, 2025.) The pink wig is also a light nod to his dastardly Vicomte de Valmont in Dangerous Liaisons (1988) and suits our conversation around his home: Les Quelles de La Coste, a 25-acre estate near the Luberon in Provence, next to the former château of the notorious Marquis de Sade (1740-1814.) A case of love at first sight: “It was spring, all the cherry blossoms were out and I had a coup de foudre,” he admits. And from 1993-2002, Malkovich and his second wife, Nicole Peyran, resided in the farmhouse full time, choosing to put their then young children—Amandine and Loewy—through the “terrific” French school system. “A little strictness can help with chaos and disarray,” he reasons. Indeed, Le Malko became a firm Francophile. “Living there opened up my life and gave me a host of opportunities,” the 72-year-old says. “A needed break from the American system, it really became a dream come true.”

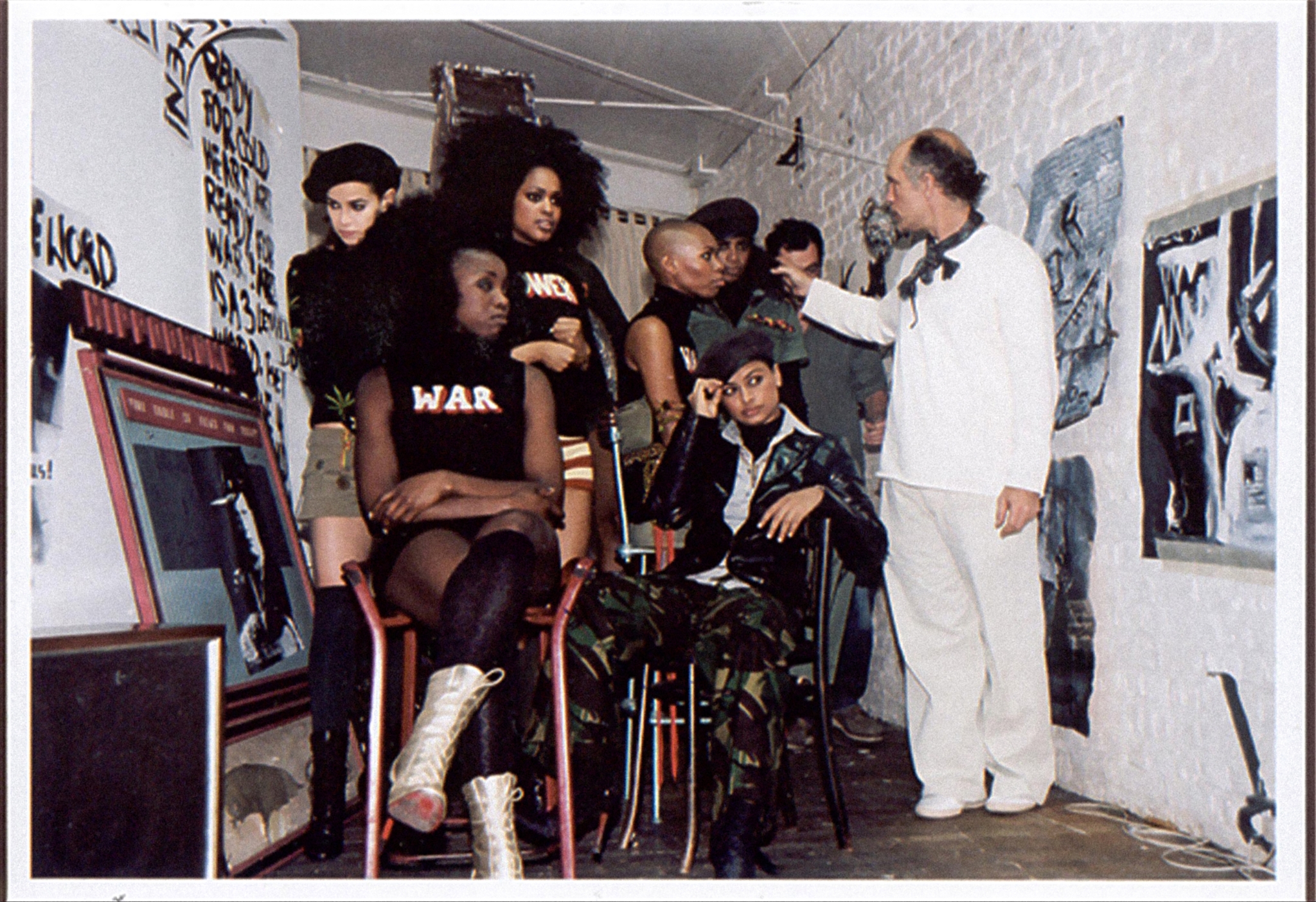

Designer Bella Freud—who often stayed at Les Quelles when they were doing their three short fashion films, Strap-Hanging (1999), Lady Behave (2000), and Hideous Man (2003, which Malkovich co-wrote and directed)—recalled “something quite Proustian about John and his life in France.” Freud appreciated the house’s nuance and depth. “He had this lovely garden with rose trees,” she continues. “My room had a Japanese bath that went all the way up to your neck. The mosaic around the bathroom’s mirror was incredible and when I mentioned it, John said, ‘Oh yeah, that’s beading.’ A real artisan, he did it all himself.” But when Malkovich drove her to the local bistro in his open-top Mazda sports car she remembers thinking, “Oh my god, this IS it!’”

Tom Stoppard, however, witnessed another side. “His house was just below mine,” the British playwright says. “From my window, I could see his basketball hoop. He would amuse himself, playing alone.” It’s a reminder of Malkovich’s roots. How his Croatian American father coached him in basketball and told him, “You’d be a better player if you weren’t so vain.” I wish I had met Malkovich’s parents. Daniel Malkovich was a director of conservation in Illinois—the type to battle an army corps of engineers, instructed to build a dam—while his brilliant mother Joe Anne (née Choisser) owned The Benton Evening News daily newspaper. Due to her voice, she was nicknamed “the frog” and though she was “agoraphobic with antisocial tendencies”, to quote her son, she was also outspoken and hilarious. When Malkovich was the subject of an Omnibus BBC documentary, featuring her prominently, directors Bernardo Bertolucci, Stephen Frears, and Peter Yates all called him up and said, “Now THAT is a star.”

Initially, Stoppard and Malkovich met in Los Angeles when the thespian co-starred in Spielberg’s Empire of the Sun (1987), with a screenplay written by Stoppard. “I like the way John acts from the inside, not from the outside,” he says. “It’s a compliment to your work.” Stoppard savoured long talks into the night about Dancer Upstairs (2002), Malkovich’s directorial film début, a political thriller that starred Javier Bardem. And he felt “very flattered” when Malkovich chose to direct Leopoldstadt, his most recent play, in Riga, Latvia (2023-2025). “Due to Covid, I didn’t see it in New York or London but I liked the subject matter,” Malkovich says, referring to the play’s Viennese Jewish history. “Since Riga was one of the places where the Nazis were, it became emotional for the audience. They were reminded of the absolute beauty and the absolute horror.”

Just as Malkovich’s move to France allowed him to direct three plays in French including Les Liaisons Dangereuses—“I felt so honoured,” he says—and star as French literary characters such as Javert in the Les Misérables TV series (2000), he worked with European directors such as Wim Wenders, Manoel de Oliveira, Volker Schlöndorff, Luc Besson, and the Franco-Chilean director Raoul Ruiz (1941–2011) who cast him in several films including his Proust project, Le Temps Retrouvé (Time Regained, 1998). The latter’s role as Baron de Charlus required speaking in French. “It was like being a baby again,” Malkovich recalls. “I had no idea and no facility with the language. And Ruiz would never reply to a direct question.” All the French actors were unbelievably helpful. “They understood how hard it was,” he says. No doubt, there was deep-seated respect for Malkovich’s bravery and steely discipline. “There’s a beauty in learning that cannot be estimated.”

“Living [in France] opened up my life and gave me a host of opportunities. A needed break from the American system—it really became a dream come true.”

John Malkovich

Having been in France for 35 years, I can now recognize those who will thrive or won’t survive in this bureaucratic yet emotionally charged country where a furious non, non, non means maybe, the next day, and other idiosyncrasies. As well as acting alongside legends such as Catherine Deneuve and Fanny Ardant, Malkovich has countless French friends. “He’s a monumental actor with such finesse,” opines the actress Arielle Dombasle, whom Malkovich has both directed and acted with. “A man filled with contradictions who has true artistic values.” Physically, he’s appreciated too. “He resembles a French gentleman farmer who just happened to get lost in the film world,” offers the Louvre Museum’s Olivier Gabet. To his added credit, Malkovich speaks softly—le must in this country—has expressed his horror of baseball caps worn backwards, and learned the language properly. A beloved village friend he still misses is Marie-Claire Eustache, a retired schoolteacher. “She had a lot of depth and was probably living on a state pension,” he says. “Her brother-in-law became one of my many coaches. He spoke such beautiful French.”

“Wine is a lot of work.”

John Malkovich

Malkovich and I either met through the musician Tom Waits, the director Damian Harris, who inspired his wig in Lanford Wilson’s award-winning play Burn This (1987), or my New York roommate Zara Metcalfe, the assistant of Susan Seidelman, who directed Malkovich in Making Mr Right (1987). Even though the film tanked—and film stars tend to flee from failure—Metcalfe and Malkovich’s friendship blossomed. She persuaded him to trade in his Concorde ticket for a pair of Air India ones, allowing a curry-a-thon in Delhi, and with characteristic irreverence mocked Malkovich’s idea of investing in Pret A Manger, her little brother’s company: an empire that eventually sold for £1.5 billion. What’s 100% certain is that Malkovich hasn’t changed. All those mesmerising performances on stage and screen and all those accolades yet Malkovich remains the same, thoughtful person, possessing a mild edge (“There are no flies on the Malkovich,” the Sex Pistol’s manager Malcom McLaren once told me). When he says, “Hi, Natasha,” in that distinctive voice, memories flood back. I think of his film production company Mr Mudd, named after the driver in his first film, The Killing Fields (1984), who confided, “Sometime Mr Mudd kill, sometime Mr Mudd not kill.” I remember Malkovich taming Metcalfe’s parrot, Oscar, a screeching harpy of the green feather variety. With hindsight, Oscar was either insanely possessive or wisely protective because whenever a male entered our apartment, he went nuts. Malkovich, on the other hand, became the Oscar whisperer. In Metcalfe’s bathroom, I would find a transformed, Jolly Roger-like Oscar cooing flirtatiously by the crouched-over actor.

There was the incident in the Connecticut supermarket, when the moral, upstanding Malkovich was introduced to the then British posh-totty custom of grazing. Shocked and appalled, he was running after Metcalfe, the actress Annabel Brooks, and myself exclaiming, “What, are you EATING? You haven’t PAID for that!” while we calmly munched through biscuits and crisps, and shoved the opened packets back in the aisles. And then there’s Malkovich’s expertise when wrapping gifts, a technique acquired when he was a young actor, moonlighting as a professional gift wrapper for Chandler’s department store. Choosing glue over sellotape says it all, as do his precise instructions on how to wrap and cross a winter scarf that bars the biting cold; reminders of his years spent at Steppenwolf, the theatrical company based in ‘windy city’ Chicago. And of course Malkovich’s imitations of fellow actors. His Dustin Hoffman made my stepfather, Harold Pinter, wheeze.

It is hard not to agree with Stoppard that Malkovich remains “rare”.

“There are interesting people who turn out to be cookie-cutter and bland, but Malkovich is a standout,” notes the playwright. “You’re in the presence of an eccentric, in a good way.” I’m actually reminded of Karl Lagerfeld (1933–2019)—another genius in his field—who happened to be my first boss in Paris. The erudite and well-read Lagerfeld constantly surprised with his patience, culture, and his ease of mixing with Hollywood, rock ‘n’ roll, and other different worlds—as Malkovich does. (Question to casting directors: why has Malkovich never played Lagerfeld?) Like other famous actors, he has directed films, designed clothes, produced wine, and owned nightclubs but, as Stoppard points out, “He’s remarkably responsible…You sense that John has to experience everything. Choose the buttons for the jackets. And go through all the emotions. He’s committed and not the type to hand over. He’s the opposite of the celebrity who gives his name but nothing else.”

Certainly, Malkovich’s decision to start a wine-growing business in 2011 was serious and considered. “It was Nicole’s idea to plant vines,” he says. “The two farmers who had cultivated and planted our land had retired, and it seemed a pity to let the land lie fallow.” Since the first harvest in 2011, Les Quelles de La Coste (LQLC) has become a quietly successful boutique vineyard, managed by Ralf Hogger who used to run Sting’s Tenuta Il Palagio vineyard in Tuscany. True-to-form, Malkovich designed the wine’s stylised label that appears unusually minimalist: the LQLC letters are more visible than the name of the estate. However, the Wine Spectator’s discerning Robert Camuto approved. He referred to Malkovich as “an actor-vintner, a late blooming enophile,” while he described his visit as turning up “a surprising cast of wines”. Whereas the vineyard’s bordeaux, Cabernet Sauvignon 2015, and rosé, Cabernet Sauvignon Rosé 2018, won a thumb’s up from the wine expert Peter Dean. “Wine is a lot of work,” Malkovich says, sounding slightly weary. Nevertheless, it did not stop him from daring to mix a Pinot Noir with a Cabernet Sauvignon; considered heresy by winegrowers in the Southern Rhône. “The original suggestion was to blend the two and call it Dangerous Liaisons,” deadpans Malkovich. “An idea that lasted two seconds.” Instead, it’s either called Les 7 Quelles or 14 Quelles 2017. “At first, the winegrowing was very exciting and surprising,” Malkovich explains. “We got good scores and also did well in the pandemic. But people now drink more cocktails and business is not what it was.” He describes the wine business as “tricky and massively competitive.” Of course, the same could be said for the film world that Malkovich has essentially mastered. Again to quote Stoppard, “John has achieved a professional coup because he always feels ageless,” he says. “You don’t remember the young John Malkovich do you?” Meanwhile, the wine world does not distract from Malkovich’s love for Les Quelles. “It’s such a personal and individual place,” he says “I’ve never had a bad day there.”