It wasn’t always about pussy. When Geoff Duke, the British world racing champion, walked into his tailor’s room in 1951, the stoney faced motorist had a simple request: a custom one-piece leather outfit that would save his knees and arms from being crushed if he fell from his bike. It wasn’t a catsuit, but was dubbed, simply, a bodysuit. Practical, protective, and easy to move in, Duke received “ribald”—old-fashioned English for pervy—jokes from his teammates. Despite the sex appeal, as the outfit became associated with women, it never lost its practical touch.

The second person to popularise the look in the early 1950s, Anke-Eve Goldmann’s new shearling-lined leather suit allowed her to combat the extreme cold during her annual trips to the mid-winter Elephant Rally. The tailored outfit also had a second innovation: a diagonal zipper that could let women easily take on and take off the suit. Images of Anke barrelling down highways in a BMW R69 and leather outfit quickly became iconic—but in the conservative post-war culture of Germany, the talented racer was never allowed to compete at higher calibre racing events due to her gender.

It’s a frustrating pattern. Beyond being a rider, Goldmann was a writer, often contributing articles about racing, especially women’s racing, and maintaining close ties to fellow novelists. Her friend André Pieyre de Mandiargues would use the catsuit-riding rebel for the central character Rebecca, telling the story of sexual liberation in the erotic fiction The Motorcycle. Working under a very male gaze, Goldmann not only broke gender stereotypes in the macho motorcycle racing world, she even founded the Women’s International Motorcycle Association (WIMA).

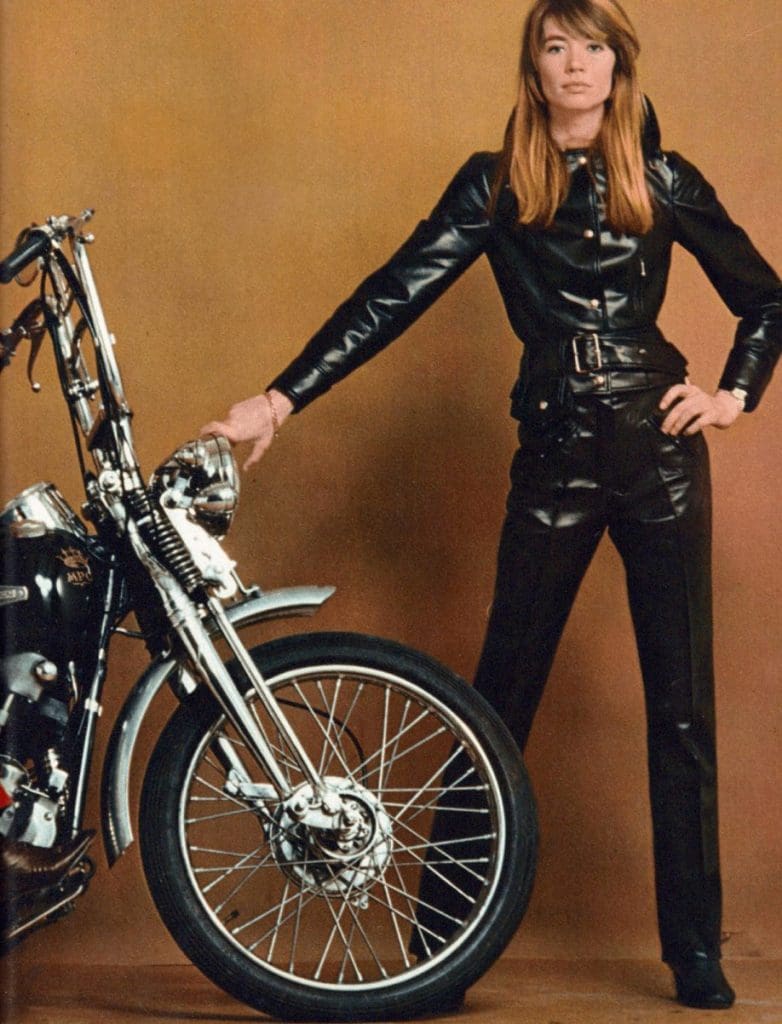

Nevertheless, the motorcycle culture continued to objectify women (Mandiargues’ book certainly didn’t help). Take one look from any poster or media from the 1960s or 1970s and you’ll find a female rider, draped provocatively across a bike (all too often safely parked). It’s showing, not doing. In tandem, with more females mirroring Goldmann’s new look, the bodysuit with its slinky feline form shifted to being called a catsuit; a trend influenced by Catwoman’s popularisation of the look as a leather-bound femme fatale.

Still—despite being wrapped up as an object of desire, there’s a rebelliousness to the catsuit that’s alluring today. It’s not about being a woman, but a rider. It’s true, the style can be flattering: cool, but never dainty. Built to protect a rider from high-speed collisions, freezing winds, hot tarmac and death, even if it came from a comic book or a male tailor, it’s the outfit of an action hero.

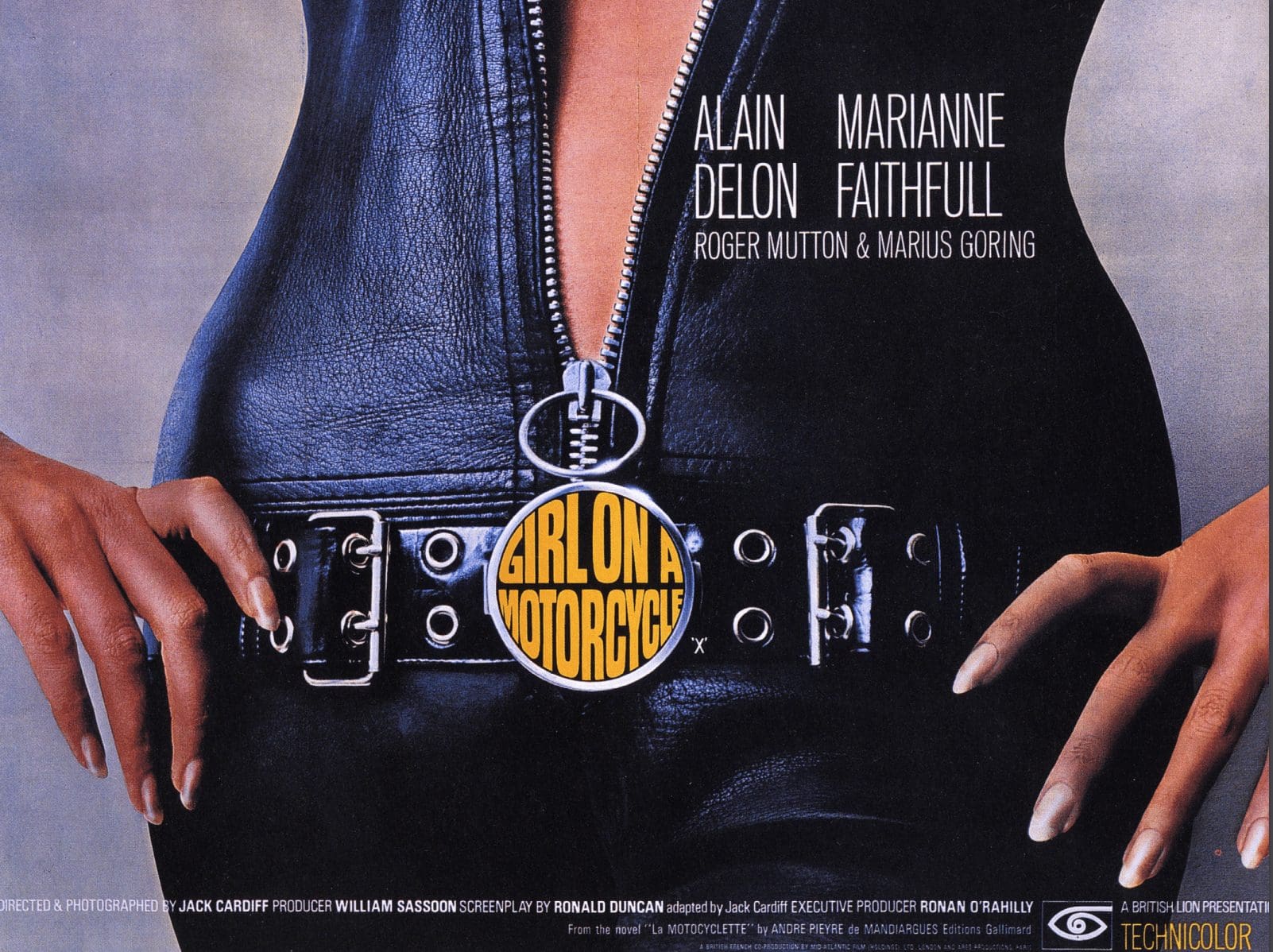

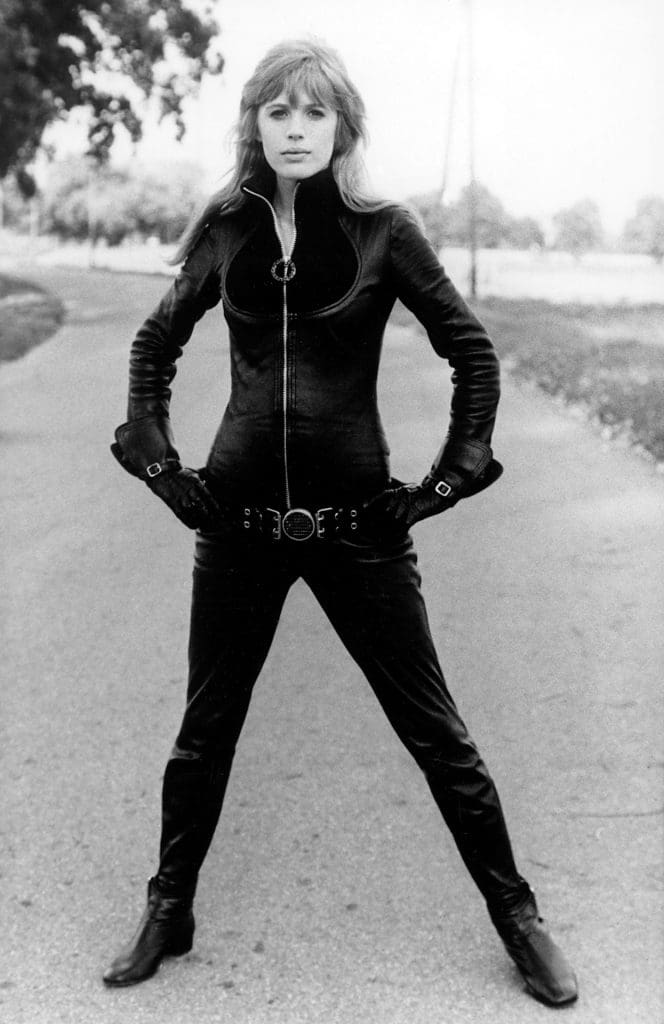

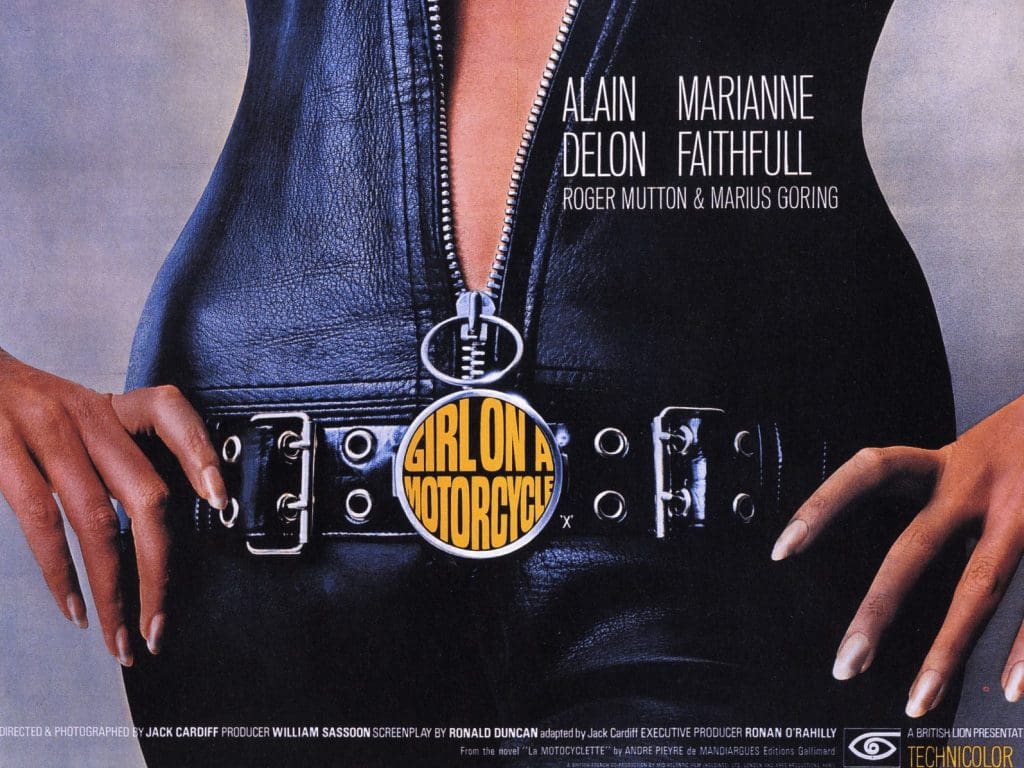

When Mandiargues’ racy erotica was adapted for the film Girl on a Motorcycle in 1968, the pop musician Marianne Faithfull’s take on Rebecca and the iconic leather outfit would only further the uniform’s difficult relationship between sex and power. Faithfull was a prominent figure in the Swinging London scene, and the film—dubbed Naked Under Leather in the US—was the first to receive an X-rating in America for graphic sexual content.

To its credit, the catsuit’s sleek leather silhouette not only accentuated Faithfull’s slimline figure, but the counter-cultural momentum of the time. A woman free to explore her life both on and off the road, Rebecca rides away from her husband to visit another lover in Heidelberg. With all the heady psychedelia of huffing gasoline, the movie falls into a bleached mishmash of drugs, affairs, and petrolheaded racing. It’s a piece that’s sexually liberating, rebellious, and defiant to gender norms, but when it all comes crashing down, the movie’s titillating poster, title, and marketing make its heroine little different to Goldmann: another biker turned into an object of desire.

Despite feeling aged, Girl on a Motorcycle still helped give some agency to women across film, fashion, and sex. Inspired by Roger Corman’s early outlaw biker film The Wild Angels and directed by Yasuhar Hasebe, the Japanese exploitation movie Stray Cat Rock: Delinquent Girl Boss moves the outfit less from sex into action; telling the zany story of a roughneck biker Ako, also leather bound, but happier knife-fighting an all-female gang of women. It’s crazy, yes, but there’s power in keeping that catsuit firmly zipped up.

Akira’s female lead Kei is another example of the suit’s progress: a hardened rebel who glides across a futuristic Tokyo with psychic precision. During the 1980s, Japan’s unique bōsōzoku biking culture (a topic touched at the end of this issue) didn’t only inspire Akira or Stray Cat, but would also see all-female biker groups exist parallel to its male gangs. For these female delinquents, the fashion options weren’t always leather, but samurai garbs and—yes—sometimes schoolgirl outfits. Tastefully, Otomo and Hasebe opt for the former, and the catsuit look becomes polished, practical, and fits a deadly persona—true to the spirit of the outfit.

The catsuit’s associations with confident, fast-moving women would become much more prominent in movies the decades after Girl on a Motorcycle first turned it into a sex symbol. In the West, the Wachowskis would ensure the outfit kept its edge with Trinity in the Matrix (we’ll ignore the regrettable alien shades). Released on the eve of a new millennium, Trinity is miles ahead of Rebecca: a sexless leather killer swerving between obstacles with such grace you’d swear someone’s plugging in the Konami code.

Never failing to be original (except for when he’s paying homage to the plot and soundtrack of Lady Snowblood), Tarantino’s Kill Bill substitutes black with yellow—and continues the look of a confident, deadly killer as The Bride tracks her first kill atop a Yamaha FZS600. Draped in a bumblebee catsuit racing down Tokyo, the look is also a clever fusion of samurai homage to the Asian cult movie that led the charge for female empowerment and a modern dose of high-speed vehicular homicide. As iconic as the updated opening outfit is, it’s worth noting that, if it wasn’t for a surprise pregnancy by Thurman, the one-suit would have been a constant look rather than the later tracksuit.

Ahead of the curve for the early 2000s, this all-business attitude was the seed of costume designer Catherine Marie Thomas. She’d remark with pride that she’d set a fashion standard for a female hero not reliant on sexuality but killer prowess: “Borrowing from the boys can be really powerful because you’re taking something as a woman, and you’re switching it around.” Today, however, she admits, androgyny is the norm—but back then, the energy felt revolutionary.

For figures like Goldmann, it wasn’t possible to navigate a male world without wanting to crash headfirst into it. Perhaps that’s why the catsuit today, in films, art, and literature, has lost a bit of its punch. We’re not as curious about what’s underneath. As Kill Bill shows, gender has become fluid, harder to define or neatly zip up. Still, if we’re barely at the end of this long trip, if the catsuit closes in on only one of its nine lives, the relative lack of provocation now only shows that the needle has shifted, and there are fresh horizons ahead.

In this issue, and, in fact, A RABBIT’S FOOT as a whole, we often look backwards and forwards through time. Ahead is a photoshoot from Maria Pawlikowska, owning the catsuit as undeniably stylish. Taking more cues from the French, her short film A Little Death is the story of a femme fatale who subsists on draining energy during male orgasm. And beyond Japanese punks, anomie, and anime, we also have Danny Lyon speaking on his cult photographic journal The Bikeriders (alongside his time with Nan Goldin and the Hells Angels hammering a nail into his ear.) Jeff Nichols discusses adapting that cherished book in his upcoming film of the same name, featuring Tom Hardy and Austin Butler. In that interview, he greets Lyon’s tatty copy like an old friend. It’s a macho, catsuit-free world in both pieces—but, with the authentic, hard-boiled 1970s setting, it’s also a sign of how far things have come.