The Fire Inside director weighs in on the film vs digital debate, pinpoints the through-line of her incredibly-varied filmography, and discusses making one of the best sports films in recent memory.

You’ve never seen a sports film quite like The Fire Inside. Though the movie—penned by Barry Jenkins and following the story of Flint native Claressa Shields (played by Ryan Destiny with an astonishing balance of grace and grit), who rose from poverty to become the first woman in American history to win an Olympic gold medal for boxing—joyfully celebrates the iconic staples of the genre, it’s unusual second-half pivot portrait of what happens after the underdog wins the big fight is what really captures the heart. “It was that exact challenge that excited me so much about the script” says DP-turned-director Rachel Morrison, whose fingerprints you’ll find all over modern classics like Black Panther, Fruitvale Station and more. “The chance to upend the sports construct, which I don’t think has ever really been done that way. It scared the hell out of the studio.”

Speaking over Zoom call, I ask Morrison about her transition from cinematographer to director. Was it a daunting experience? “The leadership on set I had in spades from my two decades as a cinematographer, I felt very comfortable working with actors,” she says, though she confesses is was the public speaking that took some getting used to. Despite this, sitting across from the filmmaker, a cool confidence emanates through each word spoken, and it’s the same level-headedness and assurance in her own voice that ensures that The Fire Inside‘s structurally-subversive ambitions remain steady, intentional, and utterly effective.

Below, Morrison weighs in on the film vs digital debate, pinpoints the through-line of her incredibly-varied style, and talks making one of the best sports films in recent memory.

Luke Georgiades: Barry Jenkins wrote and produced the film—what was the process like in terms of being chosen to direct it and I wonder if it was daunting at first going from cinematographer to director for the first time?

Rachel Morrison: When Barry wrote the script I think he always wanted a female director to helm it, there’s so much around gender in women’s sports and all these themes that a female director could lend their experiences to. I had been looking for things to potentially direct. Other directors I had worked with had encouraged me—to them it seemed clear that I had stories to tell and that I should be out there. But I love being the supporting role. I love lifting my directors up as a cinematographer. I had never set out to be the frontwoman of the band, so I had to overcome some initial fears around fronting the thing. The leadership on set I had in spades from all of my two decades as a cinematographer. I felt very comfortable working with actors, but I had a bit of a fear of public speaking, which I’ve been working on.

This project felt right for a number of reasons. I really believed Claressa’s story should be out there in the world, I was shocked I didn’t know it already. I think because of my experience as female DP—being an anomaly, having to jump through a lot of extra hoops—there were a lot of ways I could relate to the story. It felt like the right story to take a chance on.

LGs: You’re not the first DP I’ve spoken to who has said that they’ve developed a strong connection to actors.

RM: I operate too, so I’m on set with the talent hundreds of days a year. We do more set time, most directors are in and out. For me, it was by osmosis that I started to pick up on what works and what doesn’t, what inspires trust in actors and what doesn’t. I had never gone to school to study directing, or specifically studied the art of working with an actor, I had twenty years of on-set schooling.

LG: Tell me about your collaboration with Rina Yang and what you were hoping for her to bring from her toolkit on a visual level.

RM: The first thing when I decided to hire a DP was do I hire somebody who’s going to shoot something exactly the way that I would, so that I don’t have to think about it, or do I hire someone who’s going to bring something unique to the table? What I’ve learned from my years as DP is that when you allow yourself to be surrounded by different voices and ideas then the art you’re making suddenly comes to life. I don’t want to be complacent and do what I know. I knew Rina could elevate things. This is a studio film but I wanted it to have an arthouse core. I didn’t want it to feel glossy and artificial like so many studios’ movies do. I have an aversion to schmaltz and sentimentality. So I didn’t want it to be lit in a way that forces sentimentality. But I have a sensibility that tends to be really dark and grounded, which wouldn’t quite work for this film either. What Rina has is an ability to bring the elevated and the commercial together in a really effective way. It worked out really well that Rina isn’t married to operating, she likes to do a lot of live demo board operating, so the lights changing colours, dimming and brightening, and that allowed me to operate, and operating is so instinctual and integral to what I do that I now realise I probably never could have let that go. I didn’t operate every scene in the movie, but for a lot of the handheld and really emotional moments it could just be me and my actors, and I appreciate Rina for giving me that space. It was a lovely collaboration.

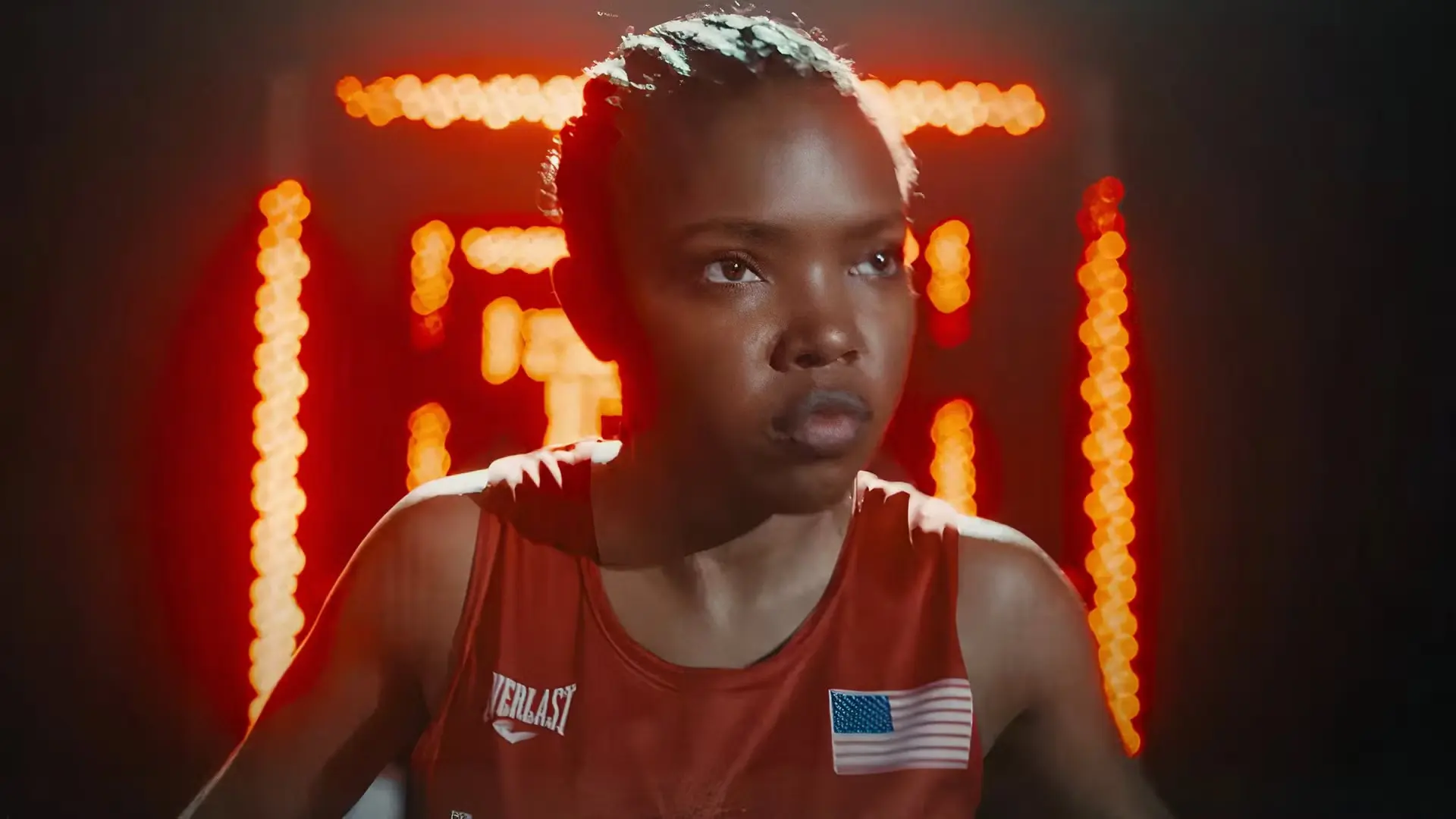

A still from The Fire Inside (dir. Rachel Morrison)

LG: I like what you said about you having this aversion to shmaltz. Sports movies can easily trip up over how sentimental they can be.

RM: Even with the score. It’s not just visuals, it’s the sounds too, and the score can so easily become something that is telling the audience how to feel, as opposed to simply amplifying the visuals.That was something I was trying to tackle with my composer [Tamer-kali], to make sure we’re giving people the space to emote without forcing it on them. Hopefully, when audiences cry watching this movie, it’s because they’re looking at the Flint community, and how much hope and pride is riding on this historic win. I wanted the music to support it, as opposed to the violins coming in, telling you that you must cry now. Audiences deserve to have their own singular experience with the movie.

LG: Was it a challenge to structure the movie with a flash forward halfway through the film? Normally, pacing-wise, the movie would be building up to the big fight as the climax, but you didn’t have the luxury of that here. How did you tackle that?

RM: It was that exact challenge that excited me so much about the script, the chance to upend the sports construct, which I don’t think has ever really been done that way. It scared the hell out of the studio. It’s been really validating to see that that flash forward is the part of the movie that audiences are really gravitating to. What happens after the win is the real heart of the movie.

LG: Something I noticed about the visuals here is that there was so often a light staring and glaring directly at the camera lens, be it sunlight, arena lights, car lights, streetlights, I wonder if that was a deliberate choice for you and Rina?

RM: It wasn’t intentional, but I think if you put two DP’s in a room together, you end up pointing the camera at lights quite often [laughs]. But if I had to reverse-engineer an answer: it was super international and represents the hope and resilience of-[laughs] no, it was totally happenstance. A friend of mine recently referenced the opening shot where she cuts across the grass, and her determination, and I said “yes, that was absolutely what I was trying to say”. People bring so much life to the intentionality of the film, which I count as a positive.

LG: Did Barry Jenkins give you any advice on how you might want to tackle this as your first feature?

RM: The biggest piece of advice from Barry was to make it my own. It was a trust. Breathe your own originality. Allow the actors too as well. To have a writer as talented and distinguished as Barry not be married to the words, and allowed us to chase authenticity, that’s what I appreciated. Authenticity is what I’m ultimately in service to. You need to believe every moment.

A still from The Fire Inside (dir. Rachel Morrison)

LG: You mentioned that you don’t necessarily have a defined style as a cinematographer, and actually you perceive that as a strength. I wonder if that perspective applies to directing now that you’ve released your debut feature?

RM: Since then I’ve looked back on what I would call a wide body of work and would say that the consistent thing throughout all the variables of genre, budget, whatever, is a real commitment to subjectivity and the experiential nature of film. You might call it heightened realism. This idea of taking the audience on a journey with a character, whether that’s through keeping a single camera feel, being very intentional with eyelines, walking into the space of characters, and that’s a style that can be applied to any genre. I needed the audience to feel like they were boxing a mile in Claressa’s shoes. They needed to be in the ring with her.

LG: What’s the key to filming a boxing fight?

RM: Part of what works about boxing films is the dynamic experience of two people fighting hand in hand in a small space. But you have boxing films that are shot with a long lens, through crowds and ropes, the spectator’s perspective, and then you have other films which are intended to be closer and wider. And we have dabbled with a few different styles, because we had so many fights in such a short period of time. Because we made the sports movie in the first two-thirds of the movie we had to frontload all of the fights, so it was important not to give people fight fatigue. We tried to film each fight differently. How do we show what it’s like to fight without your coach, who’s become this father-figure to you, by your side? That specific fight became more about capturing the abandonment she felt more than anything. My favourite boxing films were much more about the characters than how well the boxing was shot.

LG: As someone who’s worked with both, what’s your stance on the debate between digital and film?

RM: I think the biggest thing is wanting to have both options forever. They both do different things well. I’m not Nolan, who just shoots on film. I’m not Deakins, where now i’ve moved to digital and never looking back. If you can afford it, I think most movies would benefit from being shot on film, but there are disadvantages. Deakins pivoted to digital because it helped him sleep better at night. He thought: “I will be a better DP with a good night’s sleep.” I’ve experienced that. I had a commercial I worked on where our dailies got scratched. It was something that was ultimately fixed, but it put the fear of God in me. I was in the middle of directing a very well known celebrity when I got the word that actually my negatives might be ruined. That sunk me. It gives me pause everytime I think about shooting a film now. On the other hand, you can shoot a white wall on film and it will somehow still be cinematic. The hope is that we’ll always have both.

The Fire Inside is out now in UK cinemas.