“Even if I have a home in Paris and sometimes in New York, whenever I was saying I have to go home, it was going to my mother. “

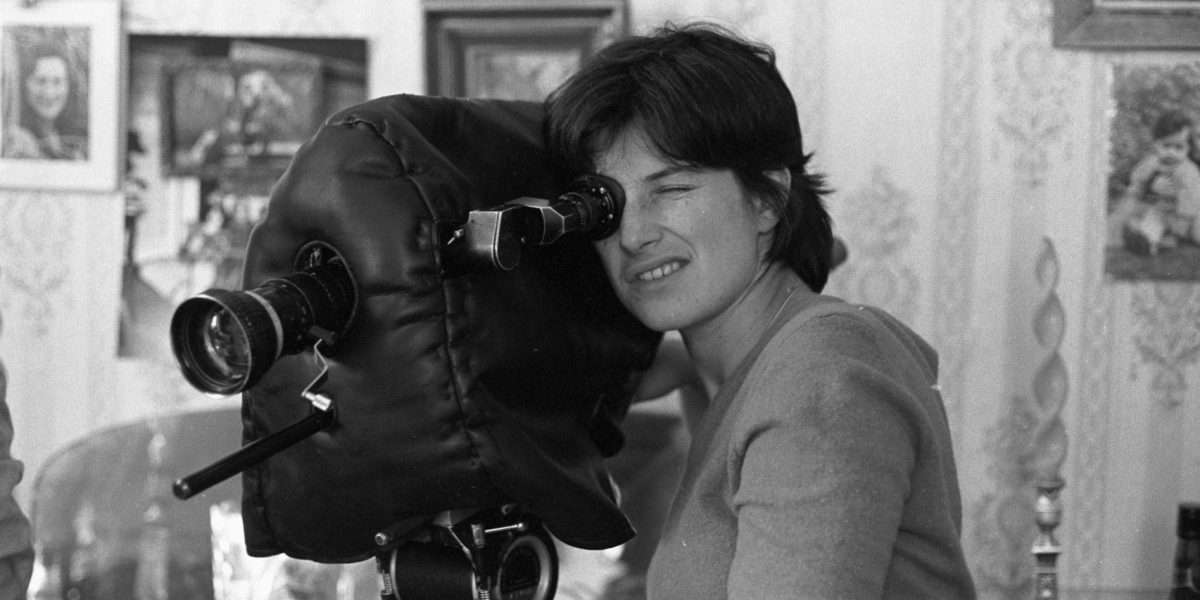

In order for someone to understand the work of Chantal Akerman, they need to understand her life trajectory.

Born in 1950 in Brussels to a family of Holocaust survivors from Poland, immigration and displacement, along with her Jewish identity, are the prominent subjects – or can be identified in multiple ways – of all of her films.

In 1971, having dropped out of film school in Brussels, she moved to New York, with her only contact being her mentor and future long time cinematographer, Babette Mangolte. It was there, where she discovered the avant-garde of contemporary filmmaking and was heavily influenced by the work of the structuralist artists.

On the 5th of October of 2015, Chantal Akerman died in Paris. Her death was reported as a suicide. She was struggling with depression for a long time, and people close to her said that the passing of her mother one year before left Chantal devastated.

Chantal Akerman was not a feminist filmmaker. As a matter of fact, she found the term very restrictive. One could say that she created a women’s cinema. She showed the way that women are experiencing and envisioning the world and by doing that, she turned cinema upside down. Through her films she kept demonstrating a motivating interest regarding the representation of women. By visualizing their stories she kept asking questions about their desires, their self-image but also the image that others create of and for them.

Presented by Le Monde in January 1976 as “the first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of cinema”, Chantal Akerman’s hypnotic and mesmerizing film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles follows a middle-aged widowed woman and her meticulous daily routine over the course of three days.

In this shockingly innovative film, where we watch the most ordinary life of a petite-bourgeoise Belgian housewife, Akerman celebrates the domestic work of a woman as a culture to almost as an art. Gestures of women that have been happening forever without being valued are elevated to an almost religious level. Because in Akerman’s cinema, we don’t discover but we look at already existing things from another angle.

The main character’s ritual, along with her attention to detail and that repetition which leads to mundanity, provoke a certain understanding and sympathy that eventually and by the end of the film will reach an absolute empathy. Her defeats are our defeats. When she cares, we care. When she struggles, we struggle. When she’s finally liberated, we, too, are liberated. And this is the first time in the history of cinema that this happens with a female character.

The influence of Akerman’s jewish family and culture are evident. In the mind of the director, the jewish ritual is replaced by the household ritual. As a matter of fact, every activity of the day is ritualized. The ritual brings peace and it keeps anxiety away. Chantal was surrounded by this kind of ritual all of her life and she was transcribing situations that were very familiar to her.

Jeanne Dielman is not really like any other film you’ve watched before. However it does remind us of the early films of Jean-Luc Godard, as well as some of the work of the structuralist filmmakers of the 70’s. Chantal Akerman produced a film that was radical both from a feminist point of view and from a cinematic point of view. Her unquestionable commitment to a female perspective – not essentially through the main character but through the director’s vision – and the groundbreaking extended shots and real time depiction, lead to a courageous and uncompromising film. Acting as a catalyst, Babette Mangolte’s perfectly aligned photographic framing changes the spectator experience, making us look at the screen in a different way. We are not following the action but we are following the image per se. Instead of point of view shots she uses a steady camera, which instantly turns the spectator to an observer.

“ I decided to make movies the same night”. That’s what Akerman said after walking out of the cinema in Brussels, having just watched Pierrot le fou, at age fifteen. But her creative birth took place in New York City, where she lived from 1971 to 1972, being around the experimental New York film scene. It was in this period that she was exposed to the work of avant-garde artists and filmmakers such as Michael Snow, Yvonne Rainer and Jonas Mekas. This was the most determining factor on her cinematography, as she would later describe. While watching films at the East Village’s Anthology Film Archives, Akerman discovered that she could break the form of the conventional cinema narrative and storytelling. The structural films were often shot in real time, with minimal setup and long takes, trying to interact with the deep inward feelings of the viewers. According to Akerman, her interest in structural cinema and its play with repetition and rhythm may originate from her jewish upbringing and her full of rituals everyday life.

In 1977, two years following the release of her masterpiece and her rise to the pantheon of the cinema d’auteur, Chantal Akerman releases the avant-garde documentary News From Home, consisting of contained, episodic long takes of Manhattan streets, parking lots and train platforms. These impersonal, beautiful, yet alienating images of Akerman’s life in New York are combined with letters that her mother was sending her at the time, read by Chantal herself. This way she created the perfect combination of the personal and the formal. This formal strictness is strikingly obvious in News From Home, which through its idiosyncratic depiction of exile could be her own version of a diaspora tale. By combining her mother’s loving but manipulating words, with images of old diners, storefronts, public transportation but never any interiors of houses or apartments, Akerman creates a sense of alienation that feels almost tangible.

But this is not the first time that Akerman uses the letter as an element in one of her films. Postal codes, failed correspondence and an almost heartbreaking urge to stay in touch, are often present in her work. Letters that are usually full of banalities and highlight the disconnection and the alienation between the correspondents, rather than their effort to communicate. And if you know that her parents are Holocaust survivors, her mother’s desperation to keep in contact becomes all the more poignant.

The way she uses space and time is almost orchestra-like. She creates tension through more subtle visual alterations, encouraging a close character study from the spectator, who grows very aware of their own physical presence. “I want people to lose themselves in the frame and at the same time to be truly confronting the space” says Akerman and the result is minimalist and rich at the same time. Amplified sounds and high definition images would become a trademark of her strictly presentational mise-en-scène.

Some months ago, Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles took the number one spot on the Sight and Sound magazine’s highly anticipated and world renowned Greatest Films of All Time Critics’ poll. She is the first female filmmaker to achieve this, since the poll’s inaugural appearance back in 1952.

Its unconventional style – the frontally centered images and the elliptical and disjunctive editing- along with its unconventional subject – a woman’s alienation from her daily routine as a housewife and its extents- made the film a powerful symbol of a period when feminism emerged both in politics and film.

Jeanne Dielman, has been analyzed and argued over for decades and whether you see it as a painstaking character study or as one of the most hypnotic and complete depictions of space and time, it definitely makes for an one of a kind captivating film experience. Akerman made this film in 1975, when she was only twenty five years old. Her real time factual presentation of a housewife’s everyday routine seemed to mock the timidity of the neorealist demand for a ninety minute film showing the life of a man to whom nothing happens.

“Often when people come out of a good film, they would say that time flew without them noticing. What I want is to make people feel the passing of time. So I don’t take two hours from their lives, they experience them. “

And to be perfectly honest, judging by her films’ ability to sell out movie theater screenings all around the world, almost 50 years after their original release, it would be only fair to say that she achieved her goal.