Kitty Grady pens her second dispatch from the Italian festival. Read part 1 here.

Sunday and Monday pass by in a blur. On Sunday afternoon, I head to the Lido. A 10 minute boat shuttle away from the city, the Lido is a long peninsula of land, 1km wide and 14km long, and far more modern than Venice proper. The festival itself was founded by Mussolini in the 1930s, and all the key buildings are in the white, neoclassical style typical of his regime. The ‘Golden Lion’, the festival’s key prize, used to be called the Coppa Mussolini. I meet Chris and Luke from my team at the Albergo Quattro Fontane, a sort of chalet-style restaurant and hotel near the shuttle drop-off which is filled with industry people and often hosts parties and junkets. There, we bump into Lina Soualem, who is on the jury of this year’s Critic’s Week—her own film Bye Bye Tiberias, explores the story of her mother, the actress Hiam Abbas (you might recognize her as Logan’s third wife in Succession) who is Palestinian. Soualem herself wears a Keffiyeh over her shoulders. She has rented a bike with which she can nip up and down the Lido with (I noticed it’s a hack shared by many more seasoned Venice festival goers).

After only a couple of spritz, it’s time for one of my most anticipated films of the festival, The Testament of Ann Lee. It is directed by Mona Fastvold, who co-wrote The Brutalist (she also happens to be married to its director, Brady Corbet). The Brutalist, which is 215 minutes-long, premiered at Venice the year before, and I remember reports of his having difficulties in shipping over his film rolls to make the festival on time. The film of course went on to a highly successful awards campaign, bagging its lead Adrien Brody the Academy Award for best actor. I had met Mona earlier on at the festival—at our Cartier dinner at the Gritti Palace. When we asked her, as one of our video questions, who she would most like to share a gondola ride, she simply replied: my husband, so she can see him (the couple are both extremely busy with projects). She also revealed that her young daughter had already at her young age been to many Venice Film Festivals in her lifetime (2 of them to see her parents’ films). The film itself is a wild ride. Amanda Seyfried plays Ann Lee, the woman who founded the Shaker religious movement which also is associated with a style of furniture and architecture. It has commonalities with The Brutalist in that it focuses on an individual who makes an epic voyage to America to found a design movement. It is a musical, but Seyfried is a long way from her Mamma Mia-image (although her voice is still as sweet). Her performance is frenetic and lustful as an ecstatically devout female messiah and I think it’s worthy of an Oscar-nomination. In one of my favourite red carpet moments at the festival, the day before she had been pictured wearing the same Versace look at Julia Roberts a couple of days prior. It’s a genius PR stunt. But I’m not sure what the evangelical Ann Lee would have made of Seyfried’s oversized tailoring.

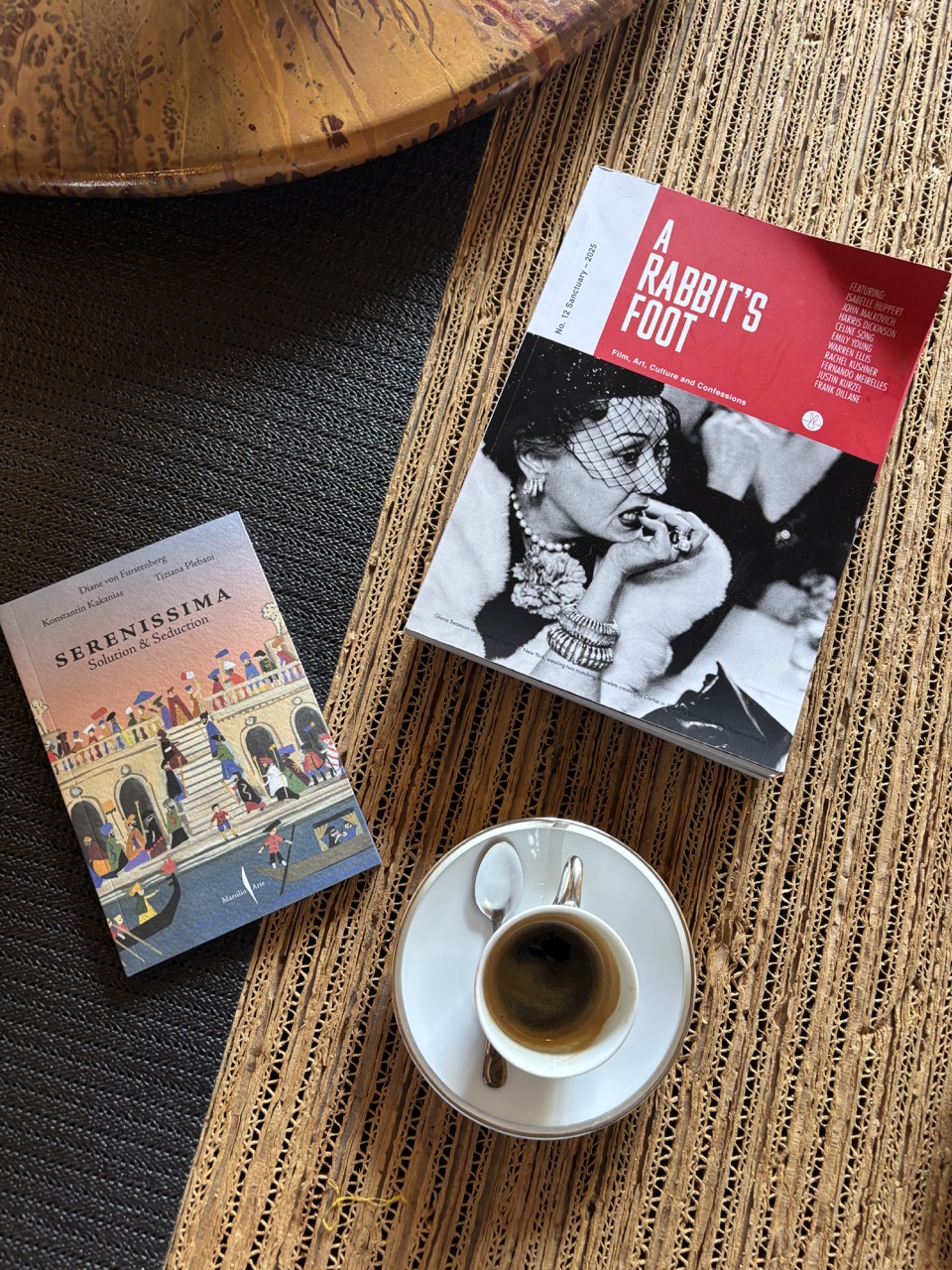

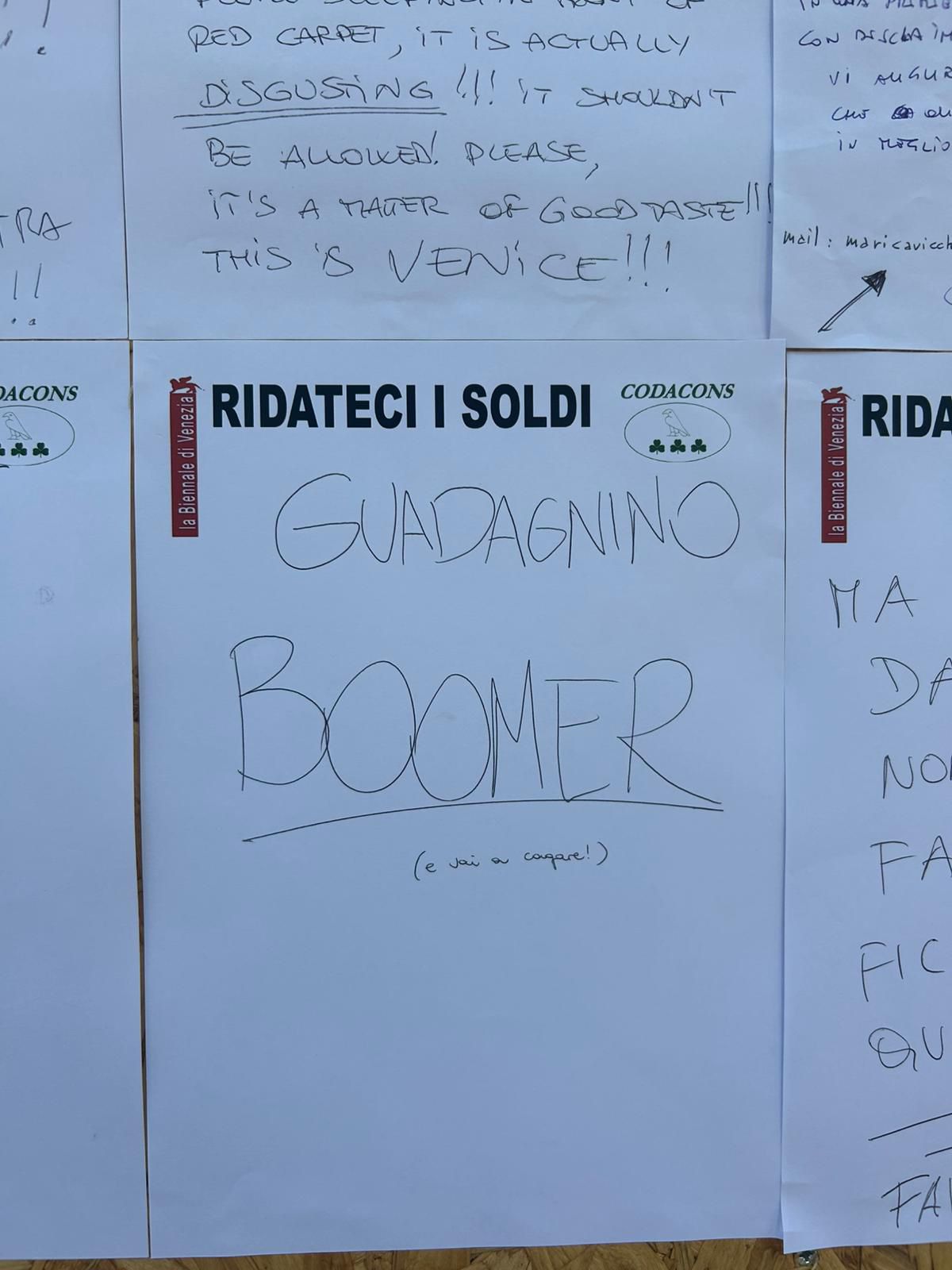

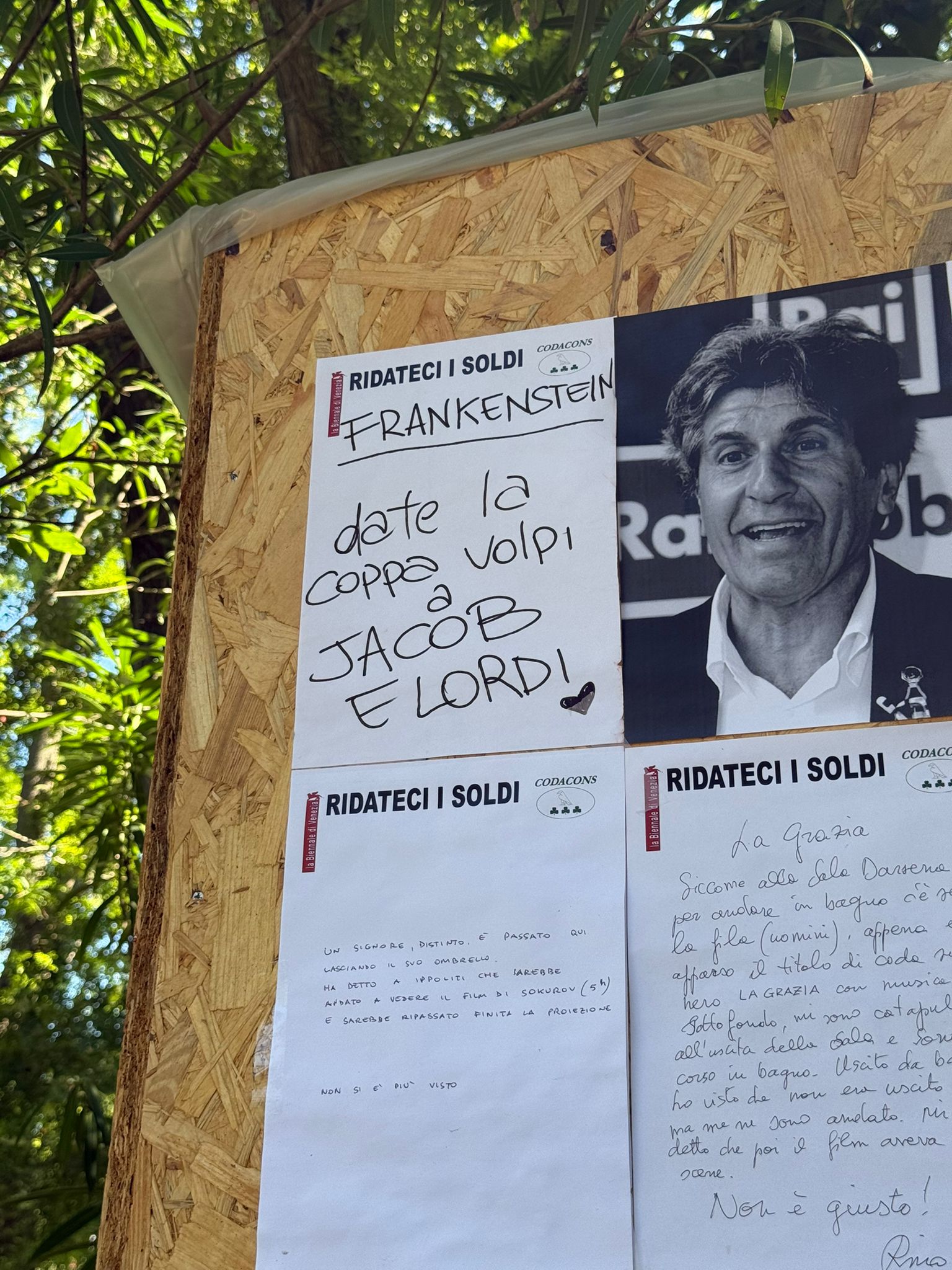

On Monday (after another trip to the Cipriani, where I spot Dior boats mooring), I meet the Magic Farm director Amalia Ulman on the steps in front of the Casino Lido. I walk past a wall of audience-made posters near the festival entrance and I chuckle at a sign that says ‘Guadagnino Boomer’ (his #MeToo drama After The Hunt, has received a mixed reception). I first came across Ulman for her work as an artist, in particular her series Excellences & Perfections, a performance piece, where, on Instagram, she played a proto-influencer who had a mental breakdown. She tells me she calls it her “first film” for the way she scripted and staged it. I am surprised when Ulman, who is Argentinian, tells me that she treats Venice Film Festival like a holiday, and the Lido, modern and on the beach, reminds her of home. She has just been to see Sofia by Marc, the Coppola documentary, which I am also about to see. It’s pure catnip for fashion lovers, going inside the office at the Marc Jacobs office in the lead up to a show. Amalia tells me she loves it because Chloë—who also stars in her film Magic Farm—makes many appearances. I get back home on an overcrowded shuttle, slightly wishing I was staying on the Lido, and could join Amalia on her holiday.

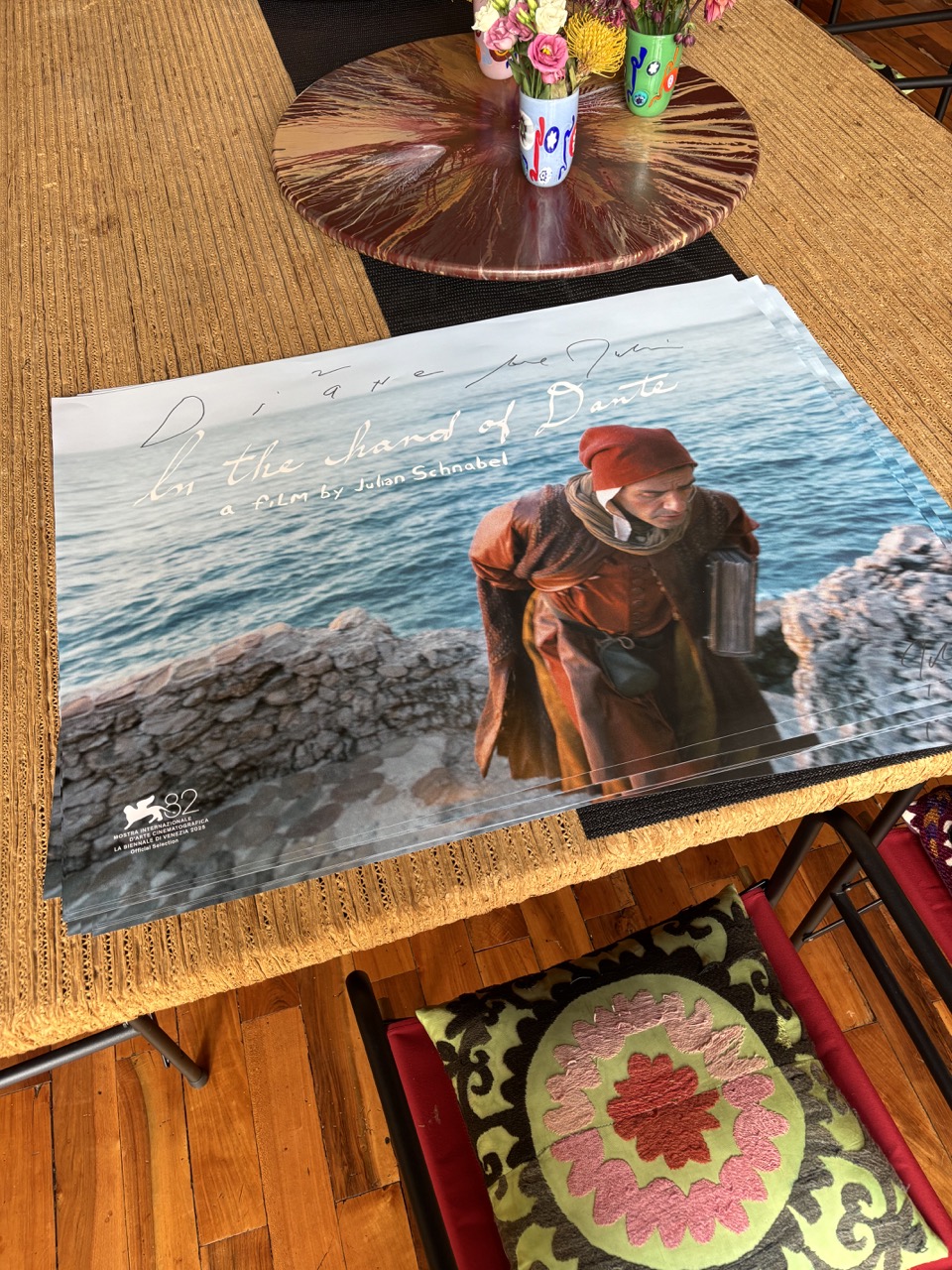

On Tuesday, I meet Fatima at Harry’s Bar (it’s my first time through the saloon-style doors). We are invited to a reception to celebrate Julian Schnabel’s film In The Hand of Dante. The film has an intriguing premise. What if a mob boss found a handwritten manuscript of Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy? Schnabel—a larger-than-life character—started his career in painting before making his first film about Basquiat. He later won the award for best film director at Cannes in 2007 for his adaptation of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. The reception takes place in an area of Venice I am yet to go to, a few minutes up the river towards the Università Ca’ Foscari in Dorsoduro. The event, co-hosted by fashion designer Diane Von Frustenberg, also happens to take place at her Venice home which occupies one floor of a palazzo. It is, to put it simply, one of the most beautiful places I have ever been to, every surface of it a testament to her taste, with clashing patterns and a mouth-watering collection of art. (I spot a diptych by Warhol and a table made by the sculptor Saint Clair Cemin). I bump into Vicky Krieps, who is in town for the première of Father Mother Sister Brother, the latest offering from indie American auteur Jim Jarmusch (and goes on to take home the Golden Lion. It’s a triptych about the guilt and awkwardness and uncanny closeness that comes with being family, and Krieps who is wonderful as the rock n’ roll sister of a bookish Cate Blanchett and the daughter of a Rampling-esque Charlotte Rampling. She dyed her hair bubblegum pink for the roll, and in Venice she has reprised the colour for the red carpet. Also at the event is her co-star Lukka Sabbat, Julian’s son Vito Schabel, Francis Ford Coppola and DVF herself, of course. We leave, walking through quieter streets of Venice, filled with shops selling masks and murano glass. In the evening I have a Hugo spritz and a plate of ciccheti with film PR Charlotte followed by a bad pizza off St Mark’s Square. She tells me she has been looking after Willem Dafoe, who is starring in Gaston Solnicki’s The Souffleur, while he is in town. Dafoe lives in Rome and is beloved by the Italian public. She recounts an anecdote. A carabinieri asked for a selfie. “Well I can’t say no,” replied Willem Dafoe. “You are literally holding a machine gun.”

I am officially sick of cappuccino and croissants. In the morning, through narrow passageways and canals I walk to a square nearby for a coffee. It’s the Don’t Look Now area of Venice, and when I spot a man walking a few metres behind me, I can’t help but feel a little spooked. I then head to the Lido for a screening of The Voice of Hind Rajab, a film by Kaouther Ben Hania. I loved her previous film Four Daughters, which tells the story of two sisters in Tunisia who are radicalised and leave their family to go to Libya. With that, Kaouther established a hybrid genre, mixing drama with documentary. In The Voice of Hind Rajab, she keeps the documentary element to a powerful minimum– the recordings of 6 year-old Hind Rajab as she called the Palestine Red Crescent after the car she was in was attacked by the Israeli military as she was fleeing Gaza City with her family. The night before, at the premiere, the film received a 23-minute standing ovation (a record for Venice), with cries of ‘Free Palestine’ resounding in the Sala Grande. It’s about as powerful as filmmaking gets, and in my own screening I find myself devastated by the story, and in particular the ending, which allows the little Hind to finish her cinematic life at the beach, a place she loved to go. The applause goes on for 10 minutes after the film screening ends, and I feel deeply stirred by the possibilities of film.

After this I go to see another devastating film by Ross McElwee called Remake. A documentarian, McElwee delves into his archives to tell the story of his son, a troubled child and sort of muse who ultimately becomes an addict and tragically dies in his young adulthood. An essayistic elegy, it is deeply moving and unflinchingly exploring his feelings of paternal culpability. There are also extremely meta moments where he remembers his films that premiered at Venice, which he came to with his son. Sat in the Sala Grande, at one point I watch the Sala Grande on screen simultaneously. The feeling is quite dizzying. In the late afternoon (after a tentative exploration of the Biennale’s palatial press area), I go and do something I normally wouldn’t do at a film festival, which is to go and see some short films. A Wave in the Ocean is the great filmmaker Jane Campion’s film school in New Zealand. The film school is sponsored by Netflix, and 7 of the short films are playing in a special strand at the festival. Taking place at the Sala Giardini, I spot Campion with her striking silvery hair on the red carpet. Most of the films seem to have been shot in New Zealand, and whilst all are different in scope—with subject matter ranging from sexual assault to queer awakening’s as a result of Jehovah’s witnesses—they all have a dreamlike, mnemonic quality in common, and I am interested to learn that Campion gets her students to work with a Jungian dream coach.

It’s my final day in Venice and there is a quietness on the Lido that I haven’t experienced yet. Most of the big glitzy premieres have already happened, and there is a refreshing peace and quiet. I still see the detritus of people camping in front of the red carpet, perhaps holding out for one last celeb spot. I start the morning with Julia Jackman’s 100 Nights of Hero. It’s not playing in competition but is an anticipated title, largely due to its buzzy cast: Emma Corrin, Nicholas Galitzine and… Charli xcx, in one of her much anticipated slew of film roles. (While waiting for the vaporetto, I overhear a French film producer refer to ‘le truc Charli xcx’). It’s a Wes Anderson-meets-Poor Things-meets–Saltburn-esque film based on a graphic novel by Isabel Greenberg, which itself borrows the story of the Arabian Nights. Emma Corirn’s character Hero tells stories so as to delay her mistress’s seduction. Charli plays a character, Rosa, in one of her stories. Her love interest is played by Tom Stourton, and I can’t quite believe I am seeing the ‘brat’ singer necking with the High Renaissance man.

After the screening—which receives woops when the beloved film critic Sophie Monks Kaufman appears on screen in a cameo—I meet Luke again at the Quattro Fontane. (He is there to interview Thai director Nawapol Thamrongrattanarit on Human Resources, one of his festival favourites.) Then I head to the Casa I Wonder, where I interview Kaouther Ben Hania about The Voice of Hind Rajab which I had seen the day before. The hotel is on the beach, and I realise it’s the first time during the festival I have actually seen sand. Ben Hania is extremely charming and speaks passionately about her film (you can read my interview here), jokingly telling one of her cast members off when they make too much noise during our junket. I also spot James Wilson, who, best known as Jonathan Glazer’s producer, is a producer on the film along with Odessa Rae and Mime Films & Tanit Films. He is with his wife, a costume designer who has styled the director and her cast for the Biennale. After this I head—extremely sweaty—to 1 Via Istria, and a more suspect location called something like Hollywood Celebrity Villas (Women in ballgowns hopefully mill around the foyer area.) I interview Jackman about 100 Nights (my interview is coming soon!). I make the mad dash back to the city, sweltering and swarming with tourists. News of Giorgio Armani’s breaks while I am on the vaporetto, but no one seems to react. I get the water bus to the airport. The journey is long, and I start to feel a bit seasick. I am glad to get back onto dry land.