In the opening scene of The Iron Claw, Sean Durkin’s new film about the Von Erichs, a family of wrestlers from Dallas, Texas, we see Fritz Von Erich repeatedly kick another man in the face. Sweat flies off his body like rain; the scene is slowed down to linger on his rage. We then cut to the dressing room: Fritz now sits in silence as a man showers naked in the background. Greeting his wife and two young boys outside, Fritz announces that he’s bought a new Cadillac, with neither his wife’s knowledge nor the means to pay for it. He tells his sons in the backseat that they have to be “the toughest, the strongest” and that they can rely on nobody but themselves. In this world, you’ve got to put yourself first.

The film doesn’t focus on Fritz but rather his grown-up sons, who live in the shadow of their father’s failed ambition to win the NWA World Heavyweight Championship. The Iron Claw the title refers to is Fritz’s signature wrestling move, one that gets passed down to his sons. Based on the real life Von Erich family, The Iron Claw deals with the tragedies that befell them in the late seventies and early eighties as they strive for the most prestigious prize in pro wrestling. These are no von Trapps. Over the course of two hours, we see death, injury, and broken dreams. What we don’t see, however, is communication. This is a film that examines the toll – both physical and emotional – that is paid when men are taught to equate strength with dignity and to valorise silence as virtue.

Sport has been used throughout film history both as an expression of masculinity and a concealer of vulnerability. (In this way, art surely imitates life.) Sometimes this has been done for laughs. Going back to the silent era, both Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd pursued sporting prowess to impress their leading ladies, in College and The Freshman respectively. Befitting the best silent film stars, more often than not they fell flat on their faces.

Falling on one’s face for a laugh is one thing. Falling on one’s face until it’s bloody and broken and getting up to ask for more is to prescribe to a dangerous masculinity, one that mistakes self-harm for discipline. So often in films, it’s the characters with the most to say that resort to physicality to make up for their lack of emotional vocabulary.

In Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, a sort of sister film to The Iron Claw, Mickey Rourke plays Randy “the Ram” Robinson, a washed-up wrestler who tries to connect with his estranged daughter, Stephanie, whom he abandoned in his heyday. Now, wrestling in the small leagues and working at a deli counter for extra cash, Randy injects his ageing body with steroids to try to preserve his former glory. But he knows how far he’s fallen. By his own reckoning, he’s become “an old, broken-down piece of meat.” He’s losing his body, but he lost his soul a long time ago. “I deserve to be alone,” he admits.

He eventually opens himself up to his daughter and tries to make up for the time they didn’t spend together, all the words he never said. “I just don’t want you to hate me,” he says, through tears. It’s a poignant moment, but Randy’s words are many years too late. In the end, he returns to the ring, their relationship unhealed. That he does so against his doctor’s wishes – Randy’s body is on the verge of a deadly heart attack – only emphasises the point: for Randy, wrestling is validation. It’s the only language he speaks. When he realises he lacks the emotional maturity necessary to repair the relationship with his daughter, it’s natural he resorts to the language of theatrical violence, even though it may kill him.

Throughout The Iron Claw, Kevin Von Erich, played by Zac Efron, has been trained to not rely on other people. In one particularly heartbreaking moment Kevin asks his mother if he can talk to her about his father’s behaviour, but is immediately shut down. “That’s what your brothers are for,” she responds. When Kevin reaches an emotional breaking point towards the end of the film, rather than confiding in his wife or friends, he pounds himself repeatedly against the floor of the wrestling ring. In many ways, Efron’s Kevin is like a twentieth century Corialanus (only with a bowl cut, Texan accent and Speedos). He doesn’t have the words to admit his frailties, only has his body.

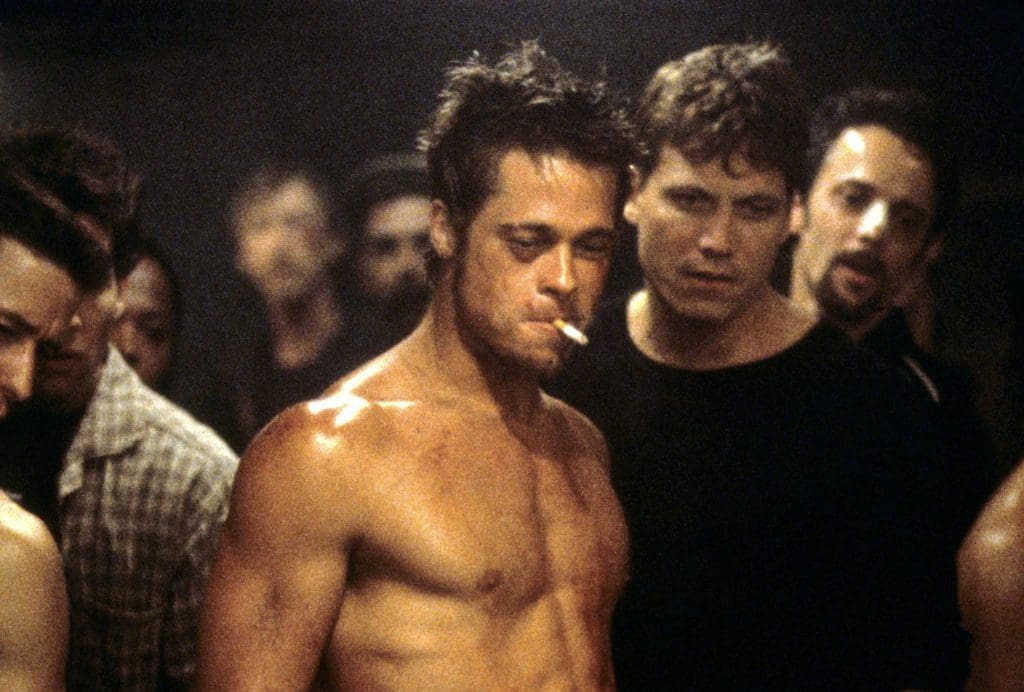

The image of a man beating himself up is familiar to anyone who has seen Fight Club, David Fincher’s much misunderstood film that helped define nineties cinema and the modern day incel. Once again, fighting is a form of therapy. Edward Norton, the nameless narrator, punches himself repeatedly in an attempt to assert his dominance over his boss. In another scene that takes place in fight club, he beats Jared Leto’s face to a bloody pulp, well beyond the point he needs to in order to win the match. As with The Iron Claw, violence, whether inflicted on oneself or someone else, is communication: it’s an expression of anguish mistaken for liberation.

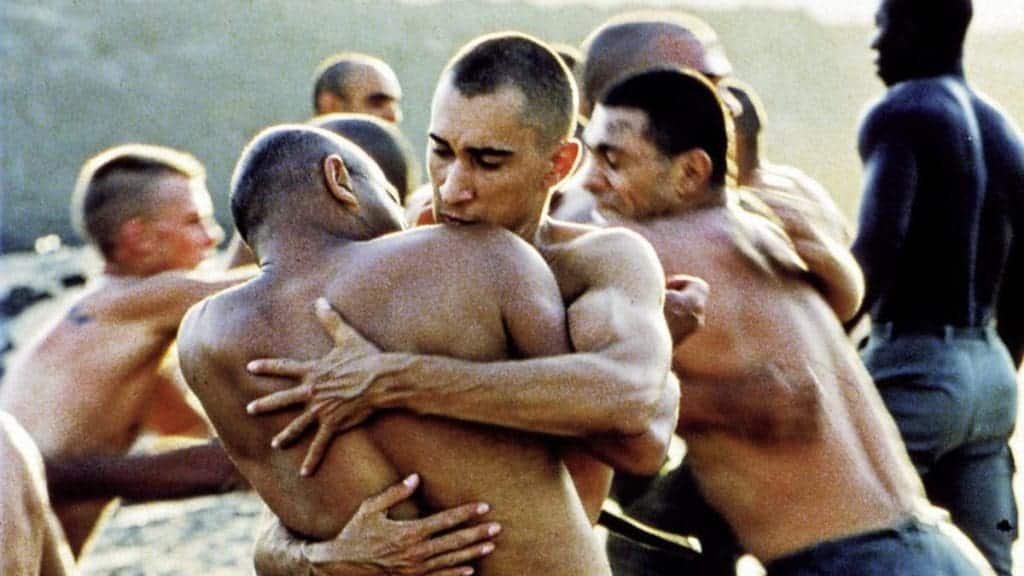

It’s perhaps no surprise that the best film about masculinity and the male body should come from a woman. Claire Denis’ Beau Travail, released the same year as Fight Club, follows the domineering Sergeant Galoup as he leads a group of French Foreign Legion soldiers in Djibouti. Hers is a film is about unspoken desire as much as it’s about militarisation of the self. Visually, Beau Travail feels more akin to ballet; Denis hired dancer Bernardo Montet to choreograph the film’s movements: scenes of soldiers training, stretching, and exercising have a flagrantly sensual quality. Homoeroticism is an unspoken theme in films like The Iron Claw, but in Beau Travail it sits on the film’s surface like sweat.. As with many other films, Beau Travail explores the trauma that precedes repression and how unspoken desire turns outwardly into rage. What separates Denis’ film, and makes it the best of its kind, is its subversion of these themes through a female gaze: in the male body, Denis finds tenderness where others see meat. The famous dance sequence at the end is a vision of liberation. Not only of the body but of desire itself. What makes it tragic is that it comes, in narrative time, after the central character’s suicide. Is it a memory or a vision of heaven?

In all of these films, physicality – through sport, endurance and plain violence – is used to convey emotion when characters cannot speak the language of vulnerability. The Iron Claw is ostensibly a film about Kevin’s journey to win the heavyweight championship. Really, it’s about his journey to cry. Though not always as subtle, The Iron Claw joins a long-list of films where sport is a metaphor for the shortcomings of masculinity. Some argue that masculinity today is in crisis, but masculinity has always been in crisis. There are ways to express emotion physically in a healthy way – through exercise, through dance. The danger comes when physicality comes at the expense of language, and when the body is pushed to unhealthy extremes. The Iron Claw does not condemn wrestling. In many ways, it’s a love letter to the sport. But it’s also a declaration of why violence is not an antidote to fear. Sadly, that’s a lesson many men are still reluctant to learn. Until they do, the cycle of pain and repression will continue. Men should confide in their mothers and dance outside of their dreams.