Three weeks before her eighty-fifth birthday, Jane Fonda was in Washington D.C for Fire Drill Friday, her event addressing our climate catastrophe. Looking fierce in her protest uniform—a red wool coat and matching fedora—the famous actor, political activist and eco warrior was her vigilant self. “Together we organised, like hell, to block the red wave [the Republicans] that the experts were predicting,” she began, thrusting her signature fist in the air. Although Ms. Fonda was then in her third month of chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, she defined ‘resistant’. Grateful that it was “a very treatable cancer,” that she had excellent doctors and then turning it around to remind, “far too many don’t have access to the quality health care I am receiving, and this is not right.”

The latter is pure Jane Fonda and her point is valid. Admire or dismiss Ms. Fonda but for half-a-century, she has fought for the underdog and loomed on the frontline of American culture as a Hollywood star, anti-Vietnam protestor, fitness guru, early feminist, bulimic survivor, bestselling authoress and twice-Oscar winner. Mistakes were made. The Hanoi Jane photo of her laughing and clapping behind the enemy anti-aircraft gun in North Vietnam, is carved in her country’s history (1972) “That two-minute lapse of sanity will haunt me until I die,” she admits in My Life So Far, her autobiography. But if she were a man, surely there would be a cutoff period?

Alan Pakula once remarked that “Jane is the kind of the lady who might have gone across the prairie in a covered wagon, one hundred years ago.” You understand what Klute’s director means. The ever-liberal Ms. Fonda is a pioneer whose startling blue eyes are set on the present. Sure, she’s guilty of being naive. Fellow activist Marlon Brando had to tell her to stop funding the Black Panthers. (The movement managed to lose both the car and credit card she’d given them.) And Fonda can forget old friends—the inevitable fallout of living several lives, as well as having moments of being dogmatic—that can happen in a rally—while her detractors like Donald Trump accuse her of using her campaigns as publicity stunts. “She’s always got the handcuffs on, oh, man. She’s waving to everybody with the handcuffs,” Trump tweeted when Fonda was arrested five times for civil obedience in 2019. But surely the arrest of Fonda and her famous friends such as Gloria Steinem, Rosanna Arquette and Catherine Keener draws media attention to the terrifying climate situation and is preferable to precious works of arts being attacked. And as demonstrated by What Can I Do? My Path from Climate Despair to Action (2020), Fonda’s book on the climate crisis, all the sales were donated to Greenpeace.

The campaigns may change but Jane Fonda is committed, even obsessively so. During the sixties and seventies, I was raised by activist parents who gathered with like-minds and spoke at demos held for Biafra, Bangladesh, Israel, author’s rights and imprisoned writers but they wisely returned to the warmth of their Notting Hill home. Not so with Ms. Fonda who wonders how best to pitch her tent and where she can “poop and pee.” She reasons in My Life So Far, her fascinating, albeit too lengthy memoir: “I didn’t want to be someone who lives on the top of a mountain and gives out money for people who live below…Mountaintops were about charity. I was about change.”

As is apparent in her autobiography and her documentary, Jane Fonda in Five Acts (2018)—set around the four key men in her life: her father Henry Fonda and three husbands, Roger Vadim, Tom Hayden, Ted Turner—she is chameleon-like. But that’s Fonda’s secret to remaining relevant every decade. A fan of the millennials, Fonda accepts that most recognise her due to Monster-in-Law (2005), her film with J Lo, while she treads softly, politely asking which pronoun she should use. As for all the media criticism of living her life out in public—her brother Peter Fonda felt betrayed by her description of their mother’s suicide—Fonda admits that she’s “still trying to totally understand the private core.” The octogenarian recently told The New Yorker. “I’m a seeker…Who am I? Like, I don’t know if I’m a narcissist or not,” wryly revealing that her granddaughter (Viva Vadim) thinks she might be. Emotionally, it’s pretty brave. Clearly, Ms. Fonda has taken Katherine Hepburn’s words to heart who warned, “Don’t get soggy; confront your fears.”

With her astonishing body of film work—Barefoot in the Park, Barbarella, They Shoot Horses Don’t They, Fun With Dick and Jane, Klute, Coming Home, The China Syndrome, 9 to 5 and On Golden Pond—Ms. Fonda could have sat back, joined the film festival circuit and rested on her laurels. Having worked with directors Sydney Pollack, Alan Parker and actors such as Brando, George Segal, Robert Redford and Meryl Streep, there would be extended interest. Instead, Fonda has done seven seasons of Gracie and Frankie—a Netflix hit—and still wants to make a difference in society. Her activism has spoken to millions, particularly women, throughout the world for equal pay and teenage pregnancy.

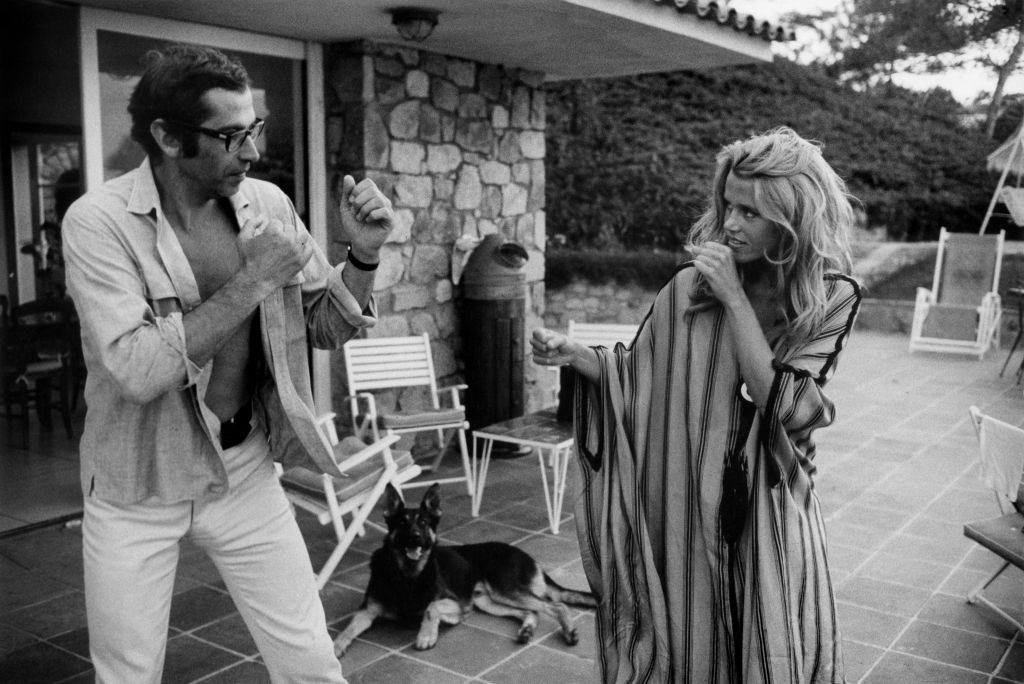

From the word go, Jane Fonda shot from the hip. Roger Vadim, her first husband, may have dubbed her Jane of Arc. The director of Barbarella was being his sarcastic, cynical French self. Still, having been a memorable intergalactic sexpot—her physique was Barbie-like—Ms. Fonda morphed into a political campaigner. When promoting They Shoot Horses Don’t They (1969), Joan Cook from the New York Times described her as “bright and articulate” viewing her “as unpretentious as a Nebraska schoolmarm and just as opinionated.” Fonda’s boundless energy and no-nonsense attitude proved to be winning qualities. In the seventies, with her shag haircut, flared jeans, maxi-leather coat, she was described as sporting a barrier chic. There she was alongside Angela Davis, the equally attractive activist and Black Panther associate. Henry ‘Hank’ Fonda was furious. “If I ever find out you’re a communist, Jane, I’ll be the first person to turn you in,” he warned.

Behind closed doors, Hank Fonda, the exceptional actor and Hollywood hero of Young Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath and The Ox-Bow Incident is portrayed as a humourless jerk. There is a heartbreaking scene in My Life So Far where he takes Jane and Peter to the circus. Instantly recognisable, they resemble a Norman Rockwell-type family except the uptight star does not address a single word to his kids. Not one slim finger pointing out the elephants or the tigers. Fonda then tortured his athletic daughter into thinking she had heavy legs. Small wonder that Katherine Hepburn—Ms. ‘Tough-as-Old-Boots’, who suffered Spencer Tracy’s macho indignities, described Hank Fonda as “cold, cold, cold” after making On Golden Pond (1981).

Watching Jane Fonda in Klute (1971) became a life-changing moment. It was her intelligence, her voice and her searing honesty. To my mind and others of my generation, there were men, women and Jane Fonda. As well as being radical and rebellious, she was Miss America with her thick hair, white teeth, neat features and perfectly proportioned figure. So imagine my excitement when Harold Pinter—my future stepfather—was commissioned to write the screenplay for Julia (1977) based on Lillian Hellman’s Pentimento, A Book of Portraits (1973) But Harold couldn’t crack it. Columbia Studios tried to sue. Fortunately, Harold fell on a sympathetic British judge who said, “Mr. Pinter tried, Mr. Pinter failed. Now get out.” And Harold’s loss became Alvin Sargent’s gain. Julia also paired Ms. Fonda with Vanessa Redgrave, her lifelong heroine and fellow activist.

To give an idea of the further dramas that Richard Roth, Julia’s producer, went through, Lillian Hellman stood up and screamed after watching the first cut. This was eclipsed by Redgrave’s Oscar acceptance speech. Unlike Ms. Fonda who said, “I have a lot to say but not here,” when receiving her first Oscar for Klute (1972), Ms Redgrave went for it at the fiftieth Academy Awards in 1978.

A pre-Raphaelite vision in her shoulder exposing dress and soft pageboy haircut, Redgrave took her time. “I think Jane Fonda and I have done the best work of our lives and I think this was in part due to our director Fred Zinnemann,” the British actress began. Pro-PLO feelings then took over [Redgrave was the voiceover for the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s recent documentary.] “You’ve stood firm,” she continued. “You’ve refused to be intimidated by the threats of a small bunch of Zionist hoodlums whose behaviour—there was an audible gasp from the audience—is an insult to the stature of Jews all over the world and to their great and heroic record of struggle against fascism and oppression.”

Redgrave was rumoured to have lost major Hollywood roles, due to her outburst. The ever-vocal Fonda has been relatively silent on her friend’s anti-Israel behaviour, keener to stress that Redgrave, like Marlon Brando, threw her off-kilter when acting; both being brilliant and unpredictable performers.

Everyone has their favourite Jane Fonda period, mine is the seventies and early eighties. Some found her presence to be too ‘Steady Eddie’ and earnest. As an audience-paying member of the public, I have to disagree. Her star-power rarely disappointed, and her films were melodramatic, entertaining, and watchable; three adjectives that now appall certain film critics.

Films like fashion catch the period. Perhaps Coming Home (1978)—leading to Fonda’s second Oscar—offered a mildly sanitised version of America’s veterans, paralysed and or traumatised by Vietnam. But the question remains whether the audience could have coped with something stronger from Hanoi Jane, the film’s producer. Coming Home still boasts excellent performances from Jon Voight and Bruce Dern.

As for The China Syndrome (1979), it was the first of its kind and remains a well-paced thriller. Jack Lemmon is credible as Jack Godell, the supervising engineer—I can still envision him watching his shaking cup of coffee—as is Michael Douglas, the fearless cameraman. Fonda’s Brenda Starr-coloured mane does date her look, but the motion picture forged its mark. The China Syndrome also exploded at the box office due to being released twelve days before the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania.

As a producer, Fonda possessed both a nose for commercial story and timing as further enforced by 9 to 5 (1980) that focuses on an abusive male boss, sexual harassment and wage inequality. After #MeToo and other movements, the upbeat comedy co-starring Lily Tomlin and Dolly Parton might seem tame. But the well-researched 9 to 5 was important for the period, helping a lot of American women who faced the patriarchal glass ceiling, professionally.

Meanwhile, it was Jane Fonda’s belief in the political ambitions of Tom Hayden—her second husband—that led to leotards, legwarmers and Jane Fonda’s Workout (1982) Exemplifying her finger on the pulse innovativeness, the book was the New York Times number one bestseller for two years as well jumpstarting the exercise video business. Making over $17 million, the JFW more than financed Hayden’s campaign. But far from being grateful, Hayden, the hero of the Chicago Seven, dismissed his wife’s exercise empire as a vanity project (“Fuck off but thanks for the check,” to quote André Previn about entitled behavior).

The marriage would end in tears. Hayden chose Fonda’s fifty-first birthday to announce his hot and heavy extra-marital affair. Fortunately, she bounced back and managed to land in the arms of Ted Turner. “I have friends who are communists,” the billionaire announced on their first date. Though their chemistry “crackled” and they shared “a common interest in the environment and peace,” his unfaithfulness ended their marriage.

Being Jane Fonda, she has forgiven all her three husbands, adamant that Roger Vadim and Hayden were terrific fathers. As for romance, she claims that part of her life is over though her ‘onward Jane Fonda’ pilgrim-like spirit continues. “When you get older, what have you got to lose?” Fonda recently told the American National Press Club. “I’m not on the market for some guy who’s scared of strong women. I’ve been married three times to one of those.”