Long after his assassination, Malcolm X’s historical legacy is still alive and relevant to us today, and so is Spike Lee’s 1992 biopic. The film was added to the Criterion collection this November, with a close-up of Denzel Washington emblazoned on the cover. He dons Malcolm’s iconic horn-rimmed glasses, gazing intently into the distance, with a blurry backdrop consisting of the Harlem Apollo and an American flag. This image from his stellar performance is taken from a scene re-enacting an electrifying speech to a captive audience.

Last month, Lee appeared at the film’s first ever Saudi Arabian screening. At the Red Sea Film Festival in Jeddah, he told the audience how he’d made the first film that was ever allowed to bring a camera into the holy city of Mecca during Hajj. “Of course, I hired a full Muslim camera crew,” he added. “The highest Islamic court didn’t agree to this because of me, but because they realised how important Malcolm X was for Islam. We were blessed. Yesterday we came full circle.”

The three-hour epic was a significant moment in Black filmmaking, and is still mentioned throughout contemporary conversations on civil rights, cinematic representation and Islam. It traces Malcolm’s personal evolution, from his early days and tumultuous journey into political consciousness, to his activism and death. Lee’s eminent role in depicting visions of Black experiences on the big screen warrants a reflection on his career’s social and political impact.

Seventies and eighties Hollywood saw a notable lack of Black figures in the industry, as investors and directors feared losing money on projects which were not deemed commercially viable. Lee, an NYU student at this time, was undeterred by this, nevertheless determined to produce and distribute his own films. Although he was preceded by a rich legacy of African-American filmmaking, his unique contributions helped galvanise a renaissance in Black cinema just before the turn of the century. Spike Lee emerged along with his contemporaries as part of a new wave, described by scholars George Hill and Spencer Moon as the “favourable years” which saw the growth of filmmakers like Julie Dash, Charles Burnett and John Singleton. This wave rippled across the pond to Black British cinema, with the likes of Menelik Shabazz, John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien simultaneously emerging. Lee and his contemporaries heightened expectations for Black films by creating well-produced and well-acted features, and he was particularly successful in employing marketing techniques, proving his commercial viability. His aptitude in navigating the industry propelled him to the top of the game; as did his ability to translate experiences onto the screen and remain profitable.

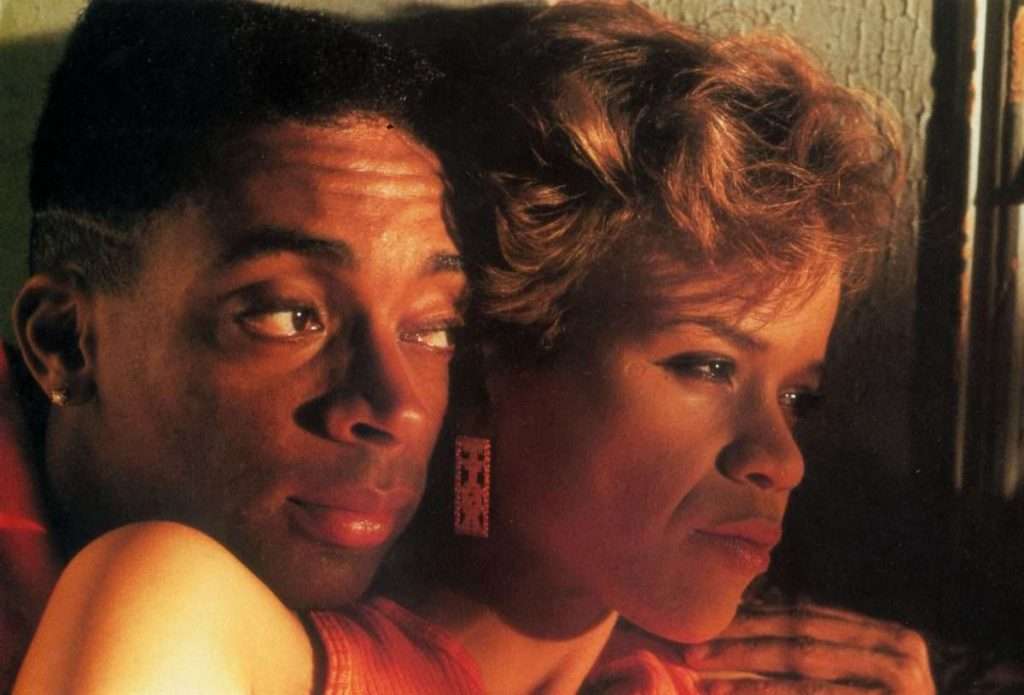

These directors burst onto the forefront of the film industry and provided nuanced perspectives of Black life on film, in opposition to the industry’s homogenising and reductive tendencies. Situated within an era of social and political conservatism, Lee’s bold rhetoric enabled his films to spark socio-political conversations. From HBCUs and interracial relationships to police brutality and Hollywood’s institutional racism, he explored a myriad of relevant topics while remaining visually alluring and sonically dynamic. His 1986 debut She’s Gotta Have It boldly explored the life of a Black woman in a polyamorous relationship, and Bamboozled (2000) saw Lee air his grievances with the industry through unashamedly satirising its legacy of minstrelsy. He’d arguably achieved the dreams of one of his predecessors, Oscar Micheaux, by becoming a nationally pre-eminent director.

His three-hour-and-twenty-one-minute biopic on Malcolm X stands as his most impressive achievement. The project itself was daunting from the outset, and not solely because of the responsibility to accurately cover X’s legacy. It had been repressed for twenty-five-years and saw people like James Baldwin temporarily sign on. But Lee took this in his stride, even acquiring a further $200,000 from Black investors—a show of black unity in line with the project’s ethos. This encouraged the studio to increase the funding by $5 million, which allowed for on-location shooting in Cairo and Mecca.

Some investors wanted to cut the final product down to two hours and neutralise its radicalism, in attempts to make it adhere to industry’s finance-driven incentives. Critics such as Amiri Baraka also feared the neutralisation of Malcolm’s life, a valid concern given the power of cinema in influencing wider perspectives. Lee recognised the enormity of the task at hand.

It is clear from the outset of the film what his meticulously considered vision was. Bursting forth with images of Rodney King’s murder and an American flag burning into a bold ‘X,’ the film immediately positions itself symbolically against all assumptions of political neutrality. In his book Framing Blackness, film scholar Ed Guerrero argues that “the ever-resourceful Lee demonstrated that, among other talents, directors of feature films must be able to organise and market their vision against opposition from all sides. In this instance, Lee managed to preserve his vision against considerable industry pressures.”

Two months after his 1964 Oxford Union debate, Malcolm said, “Islam not only makes all the scattered pieces of my life fit, it glues them together. So even though sparks still fly inside my head, I can control them before they start fires.” This poetic description is characteristic of the biography’s tone, which Lee’s film faithfully captures. Reading it is a vibrant experience, adding necessary depths and perspectives into how we understand Malcolm’s life. His relentless quest for faith and knowledge provided new avenues of making sense of the world and his place in it. The biography emulates this process, converting his shrewd recollections and candid tone into a visual form.

As a whole, the masterful epic covers the transformations and transitions which led to the burgeoning of his Black radical ethics. Washington’s voice-over narration carries the same self-assured vision espoused in the biography, especially after his introduction to the Nation of Islam, and his awakening political consciousness in prison. It is a revelatory and forceful film, an immersive odyssey into one man’s spiritual metamorphosis. The film’s poignancy peaks just before his final speech in Harlem, with Sam Cooke’s ‘A Change is Gonna Come’ accompanying the use of a dolly shot. Denzel is quietly potent in this scene, aware of his imminent demise. The audience has no choice but to agonisingly await the inevitable.

As a whole, Malcolm X remains a strong, heartfelt and empowering depiction, which contemporary movements against structural anti-Black racism highlight the importance of remembering histories of civil rights. During his career, Lee has produced films on other moments of national significance, such as the church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama and the experiences of African-American veterans of the Vietnam war and World War II.

His remarkable use of the artform to also depict Black Joy also explains his popularity and success with audiences. Whether it’s the smooth sounds of Prince complementing the bold colours in Girl 6, or the emphasis on familial joy and communion in Crooklyn, Lee uses sound and colours to dynamically depict quotidian aspects of black life with care and consideration.

Do the Right Thing is a great example of this. The work of long-time collaborator Ernest Dickerson’s cinematography was crucial to its visual palette, imbuing each frame with the serene feel of a hot summer’s day. Rife with comedic exaggerations, vibrant vignettes of black life and charming eccentricities, a Bed-Stuy neighbourhood becomes a microcosm for a myriad of African-American experiences. Employing coming-of-age narrative devices, the move from harmony to escalating chaos warns of the dangers of ignoring racial tensions. It maintains its naturalistic and life-affirming ethos, and reminds audiences of the individual agency they possess despite existing within unequal power structures.

The film was misunderstood by the press at Cannes, some of whom audaciously claimed it would spark riots. It was also overlooked by the Oscars—as was Malcolm X. But audiences are free to reach their own conclusions, as he synthesises both Malcolm X and Martin Luther King’s quotes and emphasises the necessary use of both love and radicalism in achieving equal rights. Lee’s cinematic legacy is a testament to this dualism. A monumental trailblazer who calls out the industry for its problems, whilst pragmatically exercising his agency within its pre-existing structures. Since the eighties, the industry has witnessed a growth in Black filmmaking and the emergence of other talented storytellers, culminating into Moonlight’s monumental Best Picture win at the 2017 Oscars.

At the Saudi press conference, Lee spoke of wanting to accurately depict Hajj, as the communal experience inherent to this religious practice couldn’t be recreated elsewhere. Whether it’s the scene in the film or the chapter of the book, it remains abundantly clear what a transformative experience this was for Malcolm. Thousands of miles away from his American life, Hajj provided him the spiritual vision necessary to envision a better future and reiterated his inherent dignity as a human being.