The south of France has long been a muse for many directors, from Pagnol to Godard. Chris Cotonou looks at the latter’s madcap classic Pierrot Le Fou (1969) in the second of three essays investigating the enduring cinematic appeal of the sun-drenched Riviera.

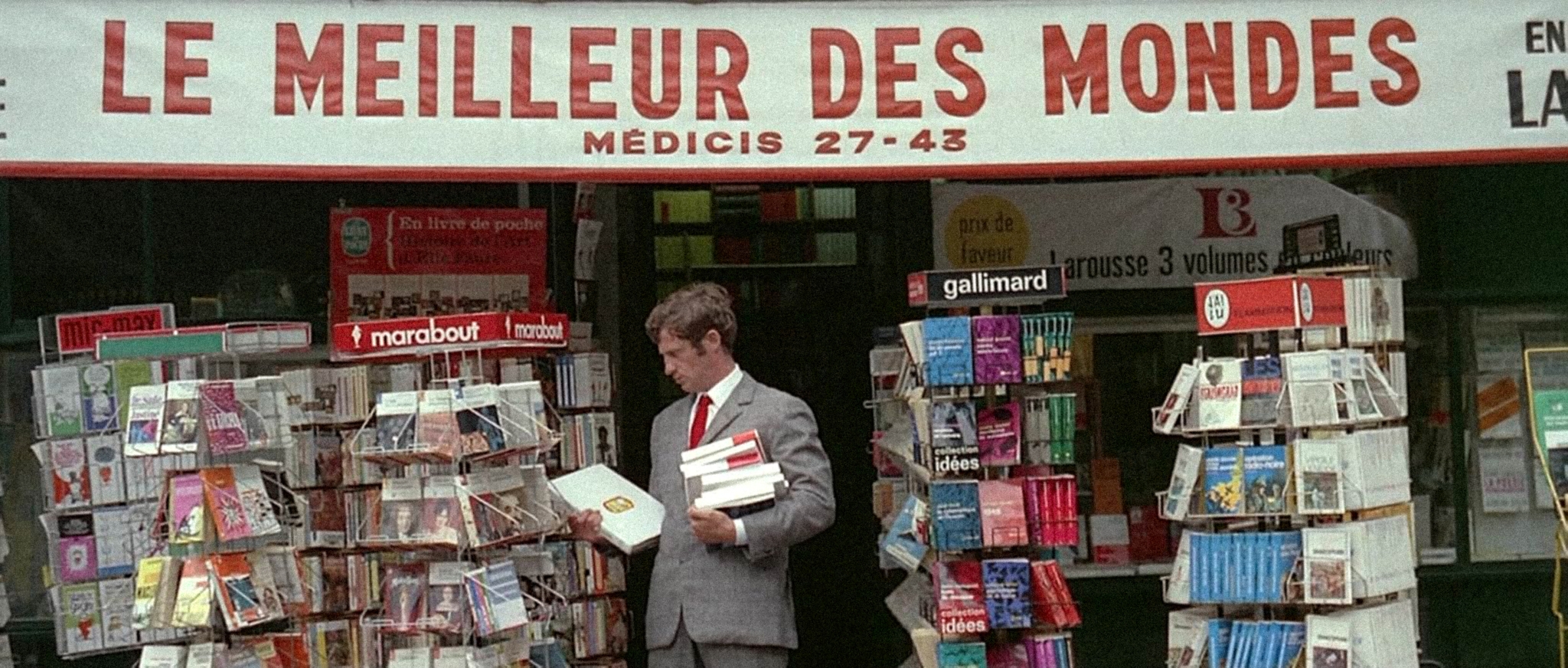

Ah, the French Riviera. That escape to the south, away from your job and middling ambitions. Away from your life. Away from your wife, even, as Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Ferdinand (or Pierrot) flees Paris to elope with his children’s teenage babysitter, the pretty Marianne (Anna Karina), on a sudden trip au Sud in Pierrot le Fou (1965). What beckons? Gun runners, musical numbers, explosions, double-crossing, and the philosophical virtues of Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954). Jean-Luc Godard’s classic, considered by many to be his best, is an experimental, fun movie with visual treats (a blue-faced Belmondo one of them; the screen endlessly awash with the beauty of the glittering sunlight on the skin of the sea, another). It is also absolutely mad.

Like Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960), Pierrot le Fou puts us in cahoots with a man whose failed literary and philosophical ambitions have driven him to the edge. Ferdinand’s dialogue is heavy with Godard’s own sentiment and cynicism, written the day before production. It is also full of cryptic lines of dialogue that likely reference his failed marriage and divorce to Karina. He is Pierrot le Fou. He is searching for something through his young muse. In the end— both in life and cinema (should the two have ever been separated with Godard)—she eludes him.

In one famous conversation, Ferdinand asks why Marianne seems so sad. “Because you speak to me with words and I look at you with feelings,” she replies. Not long after, we get a glimpse into his pseudo-intellectual narcissism when he recites his writing. “That’s the problem. You’re waiting for me. I enter the room… that’s when I start to exist for you. But I existed before… I had thoughts.” For all the violent chaos and wacky fourth-wall-breaking dialogue, Ferdinand is often read as a regretful (or otherwise) conduit for Godard’s own sentiments toward his relationship with Karina. Pierrot le fou translates to Peter the idiot—anything but smart and intellectual. And where better to enact his personal story than by the sea on the stunning Côte d’Azur?

Then there’s the film’s art style. A surprising counterpoint to Godard’s noirish Paris flicks, or his previous sci-fi work Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le Fou is remembered most vividly for its use of colour—a delightful pairing with the natural abundance of colour in the French Riviera. In the 1960s, Pop Art was a defining artistic movement and its influence is felt in the movie. In various scenes, Ferdinand’s Yves Klein Blue face paint, large pieces of text foreshadowing the plot, and the use of cartoonish dynamite sticks might well be found in a work by Roy Lichtenstein. It is a reference to the 1960s element of mass culture that Godard famously sneered at and satirised. But then, in Pierrot le Fou, there is as much beauty as there is vulgarity in the French Riviera—and perhaps a glimmer of hope. As Godard’s Ferdinand says: “Ten minutes ago, I saw death everywhere. Now it’s just the opposite. Look at the sea, the waves, the sky. Life may be sad, but it’s always beautiful.”