The south of France has long been a muse for many directors, from Pagnol to Godard. In one of three essays exploring the endless appeal of sun-drenched Riviera classics, Luke Georgiades delves into the heady world of La Piscine (1969).

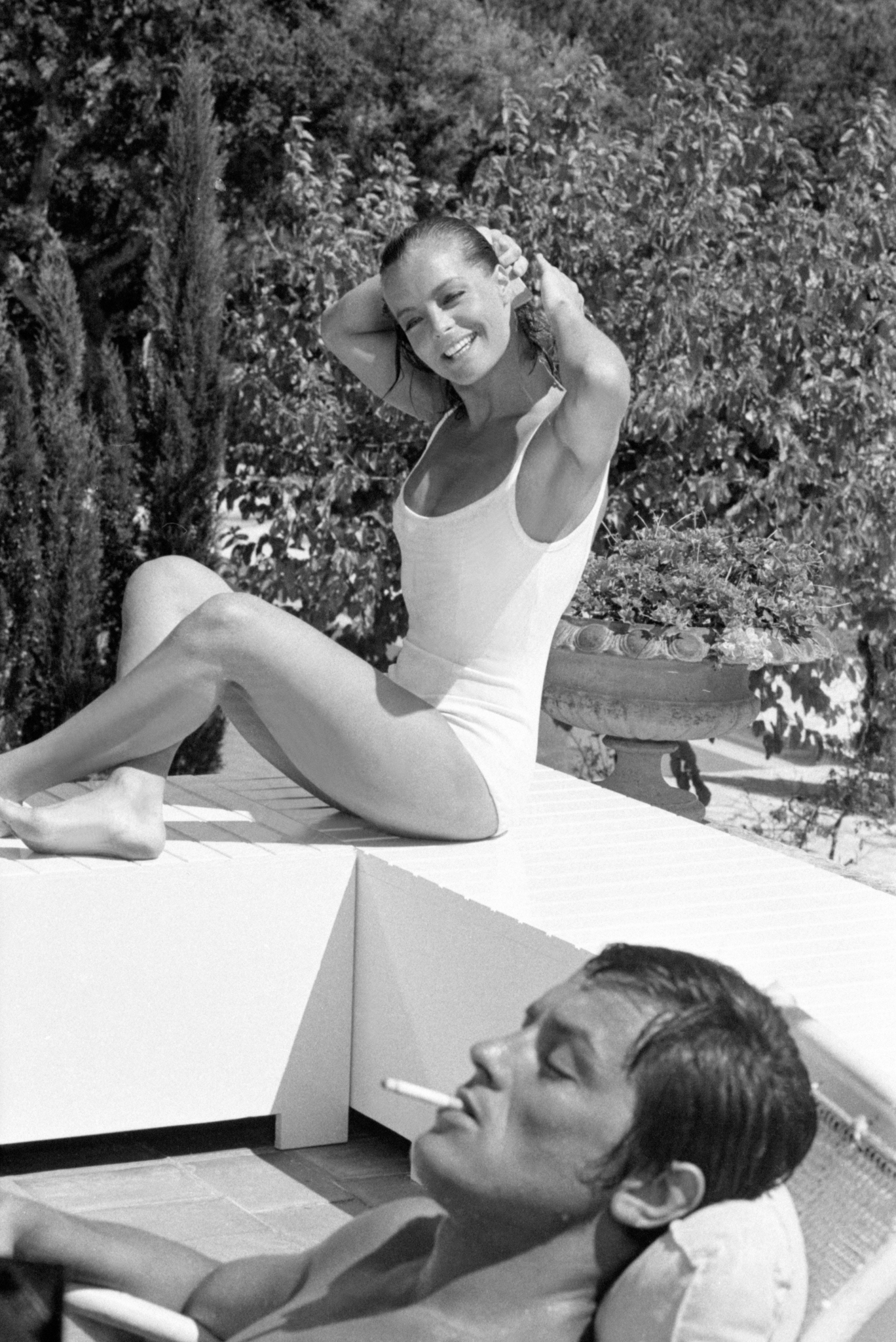

Sex is a game best played under the beating sun in Jacques Deray’s erotic thriller La Piscine (1969), following Alain Delon and Romy Schneider as Jean-Paul and Marianne, two lovers whose sensual summer at a south of France holiday home is upended by the arrival of their friend Harry (Maurice Ronet) and his daughter Penelope (Jane Birkin). Together, they unconsciously enter a sweaty, psychological contest of jealousy, desire, and deadly consequences.

An adaptation of an unpublished manuscript by Alain Page—who had penned the novella after a Saint-Tropez getaway inspired him to write something that would “show the dark side of that luxurious dream spot”—the film not only conjures a scenario in which four of some of the most attractive screen performers of their time seduce each other poolside for two hours, but also artfully interrogates what such a contest says about the dark roots of desire and our tendency to destroy ourselves, and each other, in the pursuit of sexual possession.

“It’s a claustrophobic setting, but without walls,” said screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, reflecting on the film’s sun-drenched setting. “They’re locked inside, but not in the physical sense. They’re locked inside themselves.”

It’s hard to imagine a world where Delon and Schneider—engaged in a hot-blooded affair at the time and whose sexual tension in La Piscine all but burns a hole through the screen—weren’t cast as the film’s leading lovers. “There was an atmosphere you could carve with a knife,” Birkin said of the chemistry between the two, “charged with sensuality.” According to Delon, the producers were initially sour on Schneider, fearing the Sissi (1955) actress too proper for such a seductive part and hellbent on casting Italian star Monica Vitti instead. In response to this, Delon had given the filmmakers an ultimatum: either Schneider was in or he was out. She was cast, and the film became one of the biggest hits of both her and Delon’s careers.

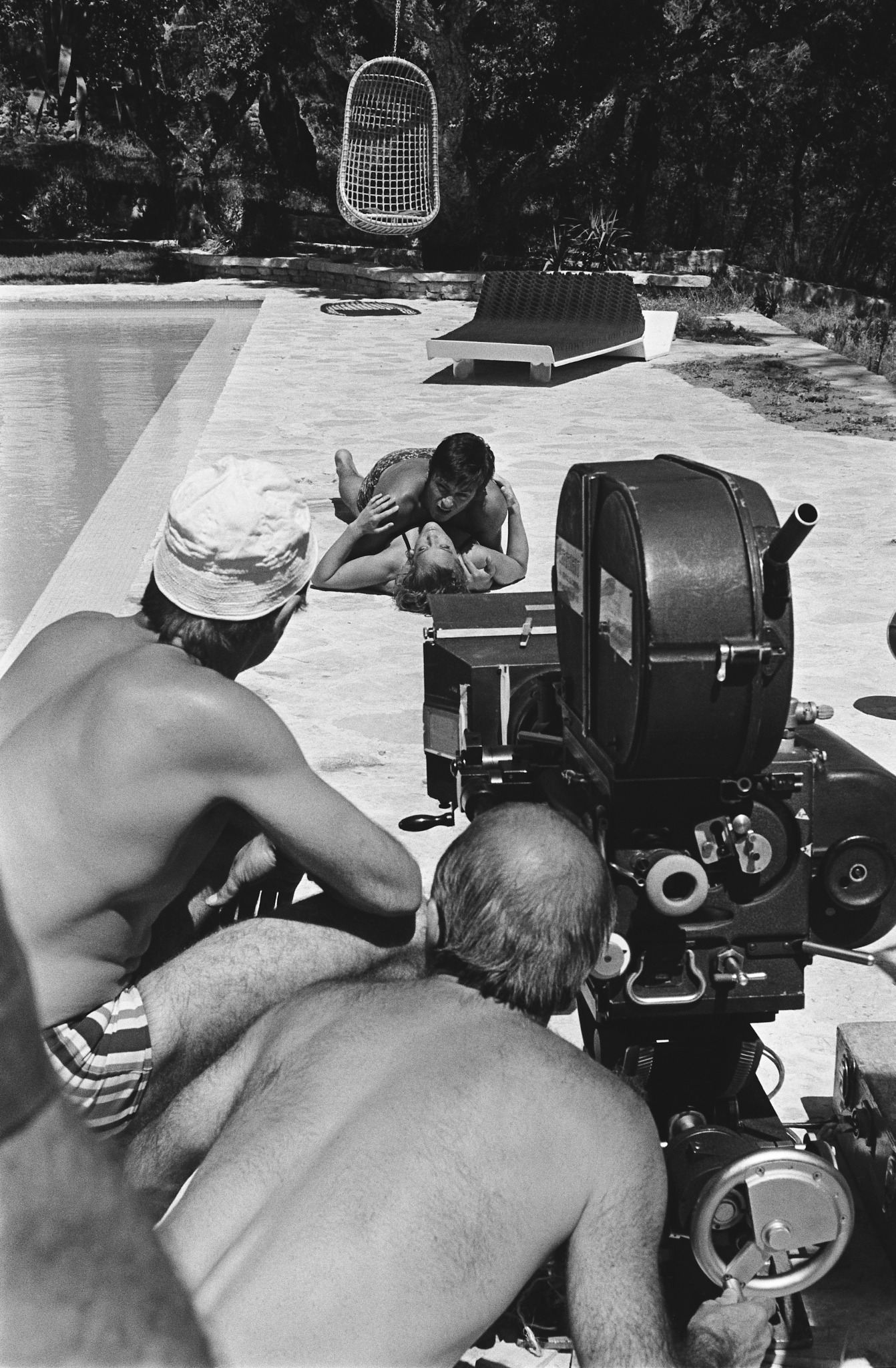

Famously shot twice, in both French and English, La Piscine only uses nine pages of dialogue. “The less dialogue you write” Deray had told Carrière, “the more you force me to use my imagination as a director.” As such, every sunkissed shot is coded with subtext. The camera doesn’t so much observe, but stalks the characters in frame, with Deray fawning over his actor’s perspiring bodies in the same way that they fawn over each other. It’s a movie teetering on the knife-edge of foreplay: between the characters on screen, for whom to feel and inflict jealousy is to experience both suffering and arousal, and between the audience and Deray, who structures his film with the intention of leading us slowly and tantalisingly to the narrative’s violent climax. In the film, a single glance contains multitudes, and what few lines of dialogue there are at once harmless and loaded with ulterior motives.

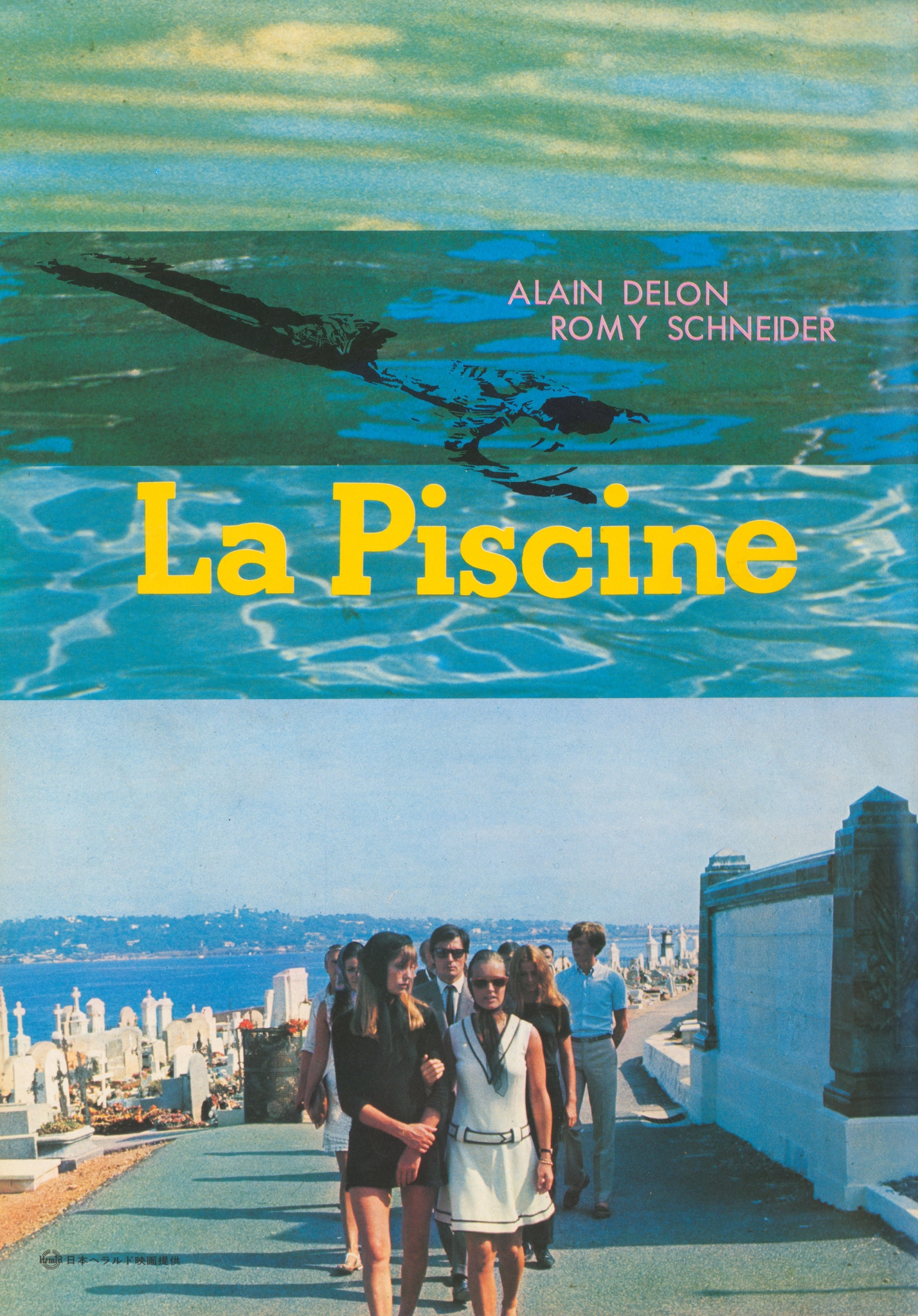

Program for La Piscine (1969).

But La Piscine’s greatest trick is never revealing the true extent of our protagonist’s deception. Though Deray hints that Marianne has betrayed Jean-Paul by sleeping with ex-lover Harry, and that Jean-Paul has done the same by seducing Harry’s daughter Penelope, he limits the audience’s own voyeurism to brief moments of forbidden touch and barbed flirtation, forcing us to become the very paranoia driving these characters to madness.

By the end of the film, Schneider and Delon’s characters are left in emotional purgatory, unable to rewind time nor move forward with their relationship, victims of their own game of love. All that’s left for them is to gaze out the window of their holiday home into the swimming pool: their secret-keeper, glowing unchanged and artificial under the ever-beating sun.