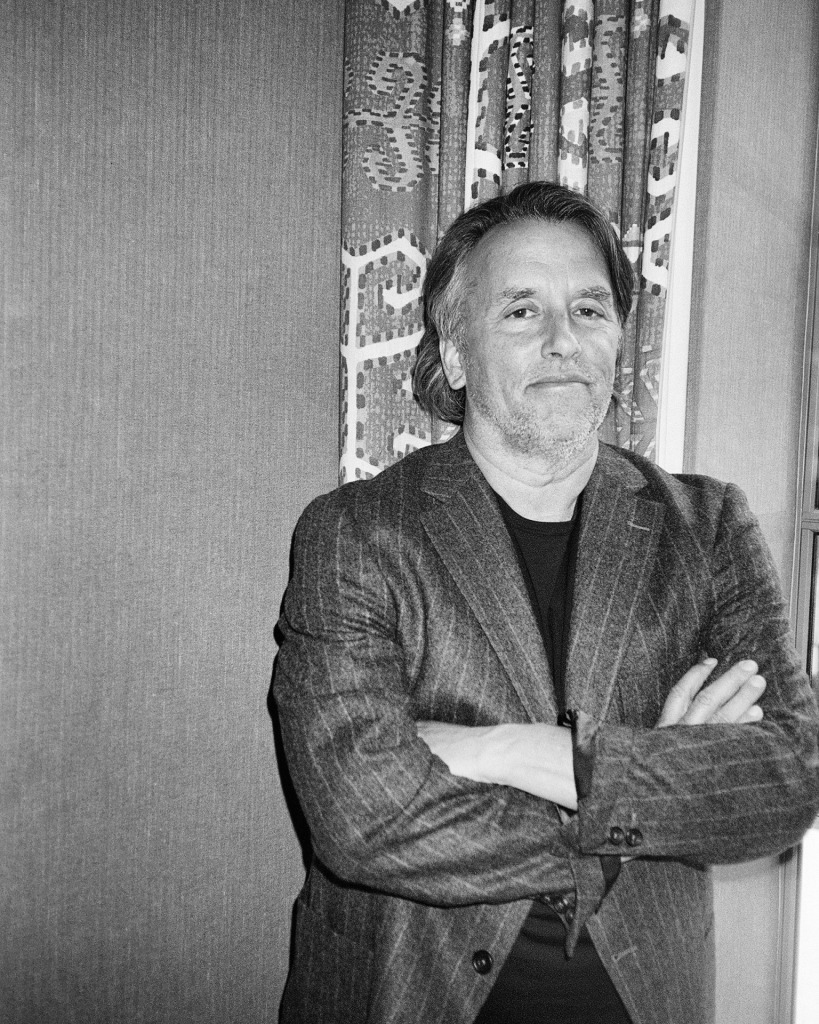

Richard Linklater is making himself comfortable, sliding so far down the back cushion of the hotel sofa where I am interviewing him that his chin is virtually resting on his chest. Allowing himself a satisfying lion’s yawn, he settles his hands just above his stomach and begins steepling his fingers, playfully, like a Bond villain. “I flew into London yesterday and it’s all starting to hit me, so I’m assuming a more relaxed posture” he explains with a Cheshire cat-like grin, before adding, “but I assure you my brain’s working fine.”

None of this strikes me as the slightest bit impolite or off-putting. If anything, the multi-award winning director’s nonchalance puts me at total ease, so much so that I start to feel like I’m talking, not to one of America’s great living filmmakers (which he is), but instead a character from one of his movies, like SubUrbia (1996), Everybody Wants Some (2016) or Dazed and Confused (his 1993 breakthrough sophomore feature)—all classic “hangout movies”, a sub-genre that Linklater more or less pioneered and has since become intrinsically tied to his cinema.

Tied to, but not defined by: One of the shining characteristics of Linklater’s auteurism is that his work is malleable. In other words: there’s not just one kind of Richard Linklater film, but you can be damn sure that every film of his is going to feel like it was made by Richard Linklater, be it a studio comedy (School of Rock), an arthouse experiment (The Before Trilogy (1995-2013), Slacker (1990), Boyhood (2014)), or a rotoscoped dreamscape (Waking Life (2001), A Scanner Darkly (2006).

Malleability is at the core of Hit Man, an ingenious fusion of noir and screwball comedy that treats identity as something to be continuously moulded like playdough rather than something determined at birth. It’s also the sexiest film of the year, tied perhaps with Rose Glass’ thriller Love Lies Bleeding. Based on a true story, Hit Man follows Gary Johnson (Glen Powell, also co-writer), a mild-mannered philosophy professor whose passion for life is long lost to the mundanity of his daily routine. On the side, Gary hustles as a tech guy for the New Orleans Police, assisting in sting operations, but is promoted to undercover hitman after accidentally discovering he has a talent for character creation. His new role, though providing newfound confidence, takes a complicated turn when he gets involved with the beautiful Maddy (Adria Arjona), who had previously attempted to hire him to murder her abusive husband.

To celebrate the film’s release in cinemas and on streaming, Richard Linklater joined A Rabbit’s Foot to discuss the sex-appeal of Hit Man, identity as a fluid concept, his perception of failure and legacy, and how to make films that last.

Luke Georgiades: Seeing Hit Man at LFF last year was probably the most I’ve laughed in a cinema since the pandemic.

Richard Linklater: Oh, good! That happened at the Venice Film Festival, and I had never had that before. They showed it about halfway through the festival, which is pretty smart, because the films up until then had been important and heavy and sometimes … .you know….bummer subjects, the world’s falling apart, stuff like that. But after we premiered everyone came up to me like “hey, thank you, that was fun!” and I was like “oh, okay, you’re welcome!” It was all “thank you, I actually had a good time at the theatre.”

LG: But it also has this philosophical backbone to it too.

RL: Yeah, it’s definitely musing about other things. But shouldn’t all films be doing that? Shouldn’t they all have some kind of layer of adult-themed complexity?

LG: Can you tell me about some of the conversations you and Glen were having while you were writing the film in terms of the philosophical themes you were trying to explore?

RL: The film explores this optimistic notion of identity: that there’s always an opportunity to become a different person, or at the very least there’s an opportunity to choose. That determinism thing of where you’re born, and here are your set points, and here’s who you are…as if you’re cast as yourself in your life, and then you play the role of “the self” for the rest of your life. And it’s like, well, wait a second, if you break down why you do everything you do, it becomes a bit more complex. I was encouraged to do this thing because I got approval to do it when I was 10 years old. Is it that simple? It’s one of those eternal questions that always fascinates me.

LG: It makes me curious about how your own perception of the idea of growth and identity has changed over the years. Because there’s nuggets of those themes in your movies from the very beginning.

RL: I see it in myself over the years. I’ve definitely changed. I was a set point guy, like, ok, I guess I’m just stuck with myself. But later I realised you can change. And that’s something the younger generation has picked up on which is kind of cool. Even the whole concept of fluid gender identity—what a great road to freedom. They believe that you can be whoever you want, and that’s pretty radical. Screw it. Don’t tell me who I am, or who I have to be. Don’t tell me I’m determined. Fuck you. I’ll be whatever I want. If you look at that in an empowering way, I just think that’s wonderful. I don’t know why people are threatened by it. I don’t know. It’s that thing again: we’re encouraged to be unique on a fundamental level then are subsequently discouraged.

LG: You released Apollo 10 ½ only a few years ago which is one of your most autobiographical, nostalgic films. Why make that film at this stage of your life?

RL: I started working on that at the time in the hopes of being ready for the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, as a kind of motivator, and of course we blew past that day, so I had it in my head for a while. It’s hard to say what motivates why you want to tell a particular story. Something just gets in you and you feel like there’s something wanting to be birthed out of you. It’s as simple as that.

LG: I was surprised at how steamy Hit Man is. Is that a quality you were trying to push because it’s something you feel has been missing from cinema as of late?

RL: I wasn’t so much trying to compensate for trends we’re seeing in cinema right now. But I knew that if this story was going to work, then sex would have to be a big part of Gary’s trajectory. It can get you killed. For Gary, It’s like “be careful what you wish for.” But that’s the growth of his character. He’s putting himself out there in a vulnerable position by declaring himself through passion, instead of sitting at home on his own where he knows nothing bad can ever happen to him. It’s like the Tin Man—he gets a heart, but then his heart gets broken. That’s the trade-off.

I knew that if this story was going to work, then sex would have to be a big part of Gary’s trajectory. He’s putting himself out there in a vulnerable position by declaring himself through passion, instead of sitting at home on his own where he knows nothing bad can ever happen to him. It’s like the Tin Man—he gets a heart, but then his heart gets broken. That’s the trade-off.

Richard Linklater

LG: What do you think of the recent debate around Gen-Z supposedly wanting to see less sex on screen in movies? Where do you think that’s coming from in youth consciousness?

RL: I can’t even believe that, that’s the only reason I went to see films as a kid, to hopefully see some sex. I don’t know. I’ve heard that too, but I can’t even fathom it. Not that we’re oversexualised or anything, it’s just…unless you’re at a kid-level, which I don’t believe either…but the only time you remove sex is when you remove the adult. Anything prepubescent shouldn’t include sex. But anything after that, anything exploring the complexity of adult life should often include sex. Maybe there’s a plot to make the world prepubescent. Keep the subject matter simple. There’s no genitalia in superhero movies. That’s not the motivator for any human behaviour in those films.

LG: This film is set in New Orleans but it’s originally a Houston set-story. I know Bernie was adapted from a story in Texas Monthly, just as Hit Man was. What do you think you continuously find interesting about the kinds of stories and people you may find in the South, because you’ve really kept your connection to those roots in a way.

RL: I guess I just have access to it, I wholly understand it. The people in Bernie or Hit Man…I know those people. But I’m interested in stories from other places for sure. We all kind of know each other, there’s just that extra layer of confidence in the South, maybe. But I never considered myself a Southern artist. I consider myself a citizen of the world.

LG: I read somewhere that you hadn’t seen any of Glen’s disguises until he would show up on set, so did you really just leave that in his court to come up with these other characters?

RL: I hadn’t seen them fully realised, but we had names for all the characters, we had wigs. We had these facsimiles of Glen’s face with the different wigs on, and there were glasses on this guy etcetera. But the final dial in was on the day, it was Glen’s little reveal moment. He definitely went off on the deep end.

LG: Which was your favourite of those characters?

RL: When Tara [Cooper], our hair and makeup person, added the freckles to the face of the orange-haired guy, that was the beautiful final step. I thought that was brilliant, getting those details.

LG: What kind of movies are you giving as homework to your cast or crew while making a movie like Hit Man?

RL: So few.The film is such a mashup of different genres. I talked a lot about film noir and screwball. But I more just assumed that the cast had seen Double Indemnity (1944). God, I hope they’ve seen Body Heat (1981). Body Heat is such a good reimagining of Double Indemnity, 40 years later, and I guess now we’re 40 years on from that.. Then you get Screwball, one of the great timeless genres, even though they can be a little embarrassing in their immediacy, because they depict a world that’s so contained in a certain moment. Like Preston Sturges films are timeless in one way but also really dated in how he depicts his world. But the dialogue, the relationships, the humour are all very sophisticated.

LG: Is there a single film whose traces could be found in any of your films?

RL: Isn’t everything post-1939 based a little bit on Wizard of Oz (1939)? Isn’t that someone’s theory? Which I would agree with. I just referenced Tin Man, so…

LG: You’re constantly taking big swings with the kinds of movies you make. Have you ever made a film that you’ve looked back on and considered a miss? Tell me a bit about how that idea of failure, or the possibility of it, fits within your approach to filmmaking.

RL: As a former baseball player, who really did take swings and misses… There’s a game where you didn’t get a home run but you hit the ball hard three times and you figured out the pitcher, and you come away going “nah, I got a little better”, even though the official record says you lost.

Something that looks like a success can sometimes make you feel like you did less good than how people are telling you you did. That’s what it is to have a high standard for yourself. You stop buying into other people’s notion of success or failure. No film was still-born to me, no matter what anyone said. Every film that I’ve made worked the way I wanted it to work. What the athlete in me wouldn’t be able to live with is “I didn’t try hard enough during that game.”

LG: Yeah, and then again, what does a film “doing well” really mean?

RL: Our industry’s not set up for consistency in that way. Even when you do have a film that’s “doing well” you have people around who are just unsatisfied. It’s almost even worse. Success only agitates people. “Well, maybe it’s not that good….” Even from a business standpoint, in the indie world it’s not the failures that depress you, it’s the successes. If you wanna get disgruntled, make a big success.

LG: Do you look back at the body of work you’re going to leave behind, the way a filmmaker like Tarantino does, or are you always looking forward to the next one?

RL: You can’t not be aware of it, you put your life into it, but I don’t really care how it’s perceived. I don’t think you can sum it up or make sense of it the way other filmmakers will try to do. You look back on other bodies of work, from writers, musicians, and even with someone you like a lot, there’s that one album or book or film you haven’t jumped into yet because you haven’t heard great things about it. But maybe that’s their best work. Maybe it’s their personal favourite. You just don’t know. The world can have a very different view from you. That’s the beauty of it. This work is sitting there for all time. You can go back and check it out whenever you want. Or not—let it fall into complete obscurity. What’s that thing? You jump ahead somewhere between a minute ago and a hundred years and “there’ll be a day you’ll have your last reader” [laughs]. Think of a graveyard. Yeah, people gather round, but at some point there’s going to be no one alive who ever knew this person. Time will certainly humble everyone. So what does it fucking matter? We’re all in some little continuum here.

Even from a business standpoint, in the indie world it’s not the failures that depress you, it’s the successes. If you wanna get disgruntled, make a big success.

Richard Linklater

LG: Merrily We Roll Along is going to be filmed over 20 years. In Boyhood there was a very practical reason for the method, because you can’t just use prosthetics to make a 7 year old an 18 year old. But with Paul Mescal, you could probably get away with using prosthetics to age him. So where has that itch come from this time to stretch out that filming process over many years?

RL: I just don’t think you could get away with it. Sure, you could do the hair and the makeup, but it wouldn’t be true, because the actor hasn’t lived that life. We’ve started on this train together and for it to work by the end they would need to have lived a life. It’s character based. You can fake the surface, but even then, the special effects show themselves pretty quickly, within a few years sometimes, because it just gets better, and so it gets worse in a way. I don’t really trust it because of that. But that’s the story I’m interested in telling. I want to work with Paul Mescal in his 40s, whatever that looks like. Neither of us can conceive of that now. I have some idea, but until we get there, we won’t know.

LG: So many of your films have found longevity in the cultural consciousness, especially with young people. School of Rock is the perfect example of that. Have you been surprised over the years to see how well that movie, and the Before trilogy for that matter, has continued to find new life generation after generation?

RL: It’s satisfying. I never wanted the Before Trilogy to be topical or fancy, I was always thinking in the eternal. Like there’s a certain level of a concept being so clever that it only works once, and that ages it and stops it from resonating. With some art, you’re making it from the future. You’re seeing it with longevity even at the moment of conception, as if it’s not something that belongs to any specific moment at all, and therefore every moment. Then at that point, you’re just reaching out to people, not only everywhere, but across time too. It’s not arrogant to think that way, you’re trying to deepen the work in a way that works beyond the superficial culture of the moment. You forgive School of Rock for its age because it’s really about these people, the personality, the situation. It is wild to meet people who weren’t born when that film was made who now love it. It’s always a surprise, and it’s always cool.