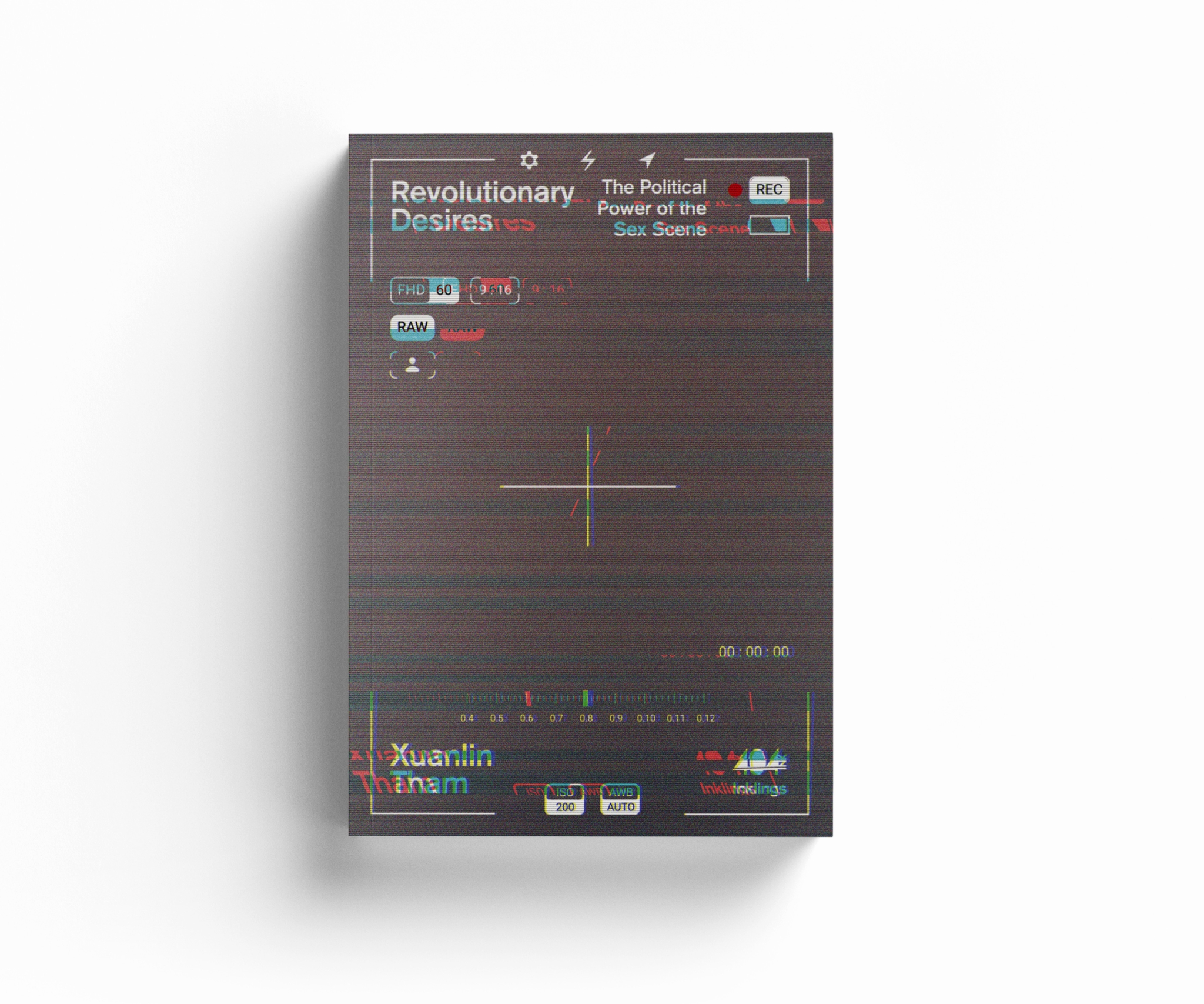

Writer and film critic Xuanlin Tham shares an excerpt from their new book exploring the political power of the sex scene. Available to order here.

I love thinking about sex. I think about it all the time. Contrary to many but in joyous company with some, I love when a movie has sex in it. I am happy to accept the label of pervert. I embrace it in a deliberate fashion. I often muse on the dictionary definition of the word ‘pervert’: to “distort or corrupt the original course, meaning, or state of (something)”; to “lead (someone) away from what is considered natural or acceptable”. I look at the path we are on now, marching to the beat of a death-driven empire’s drums; I think we urgently need to chart a new one.

This framing of perversity – as a refusal to be imaginatively shackled to paths of abjection – is what animates my interest in the sex scene as a cultural and artistic form. My book Revolutionary Desires: The Political Power of the Sex Scene emerged out of a wish to explore the sex scene as a political artefact, and discover what its shocks, transgressions, and intimacies could resource us with in our movements for liberation. It was never quite enough for me to accept the argument that the sex scene should continue to exist in the name of artistic freedom. Yes, of course, but there’s something else that needs to be named, something that felt almost spiritually important about it: an excess of feeling; a rush of pleasure, no matter how simple or complicated; the sense that we are momentarily lifted out of time. The sex scene reveals itself as a sensual, energetic phenomenon that beckons us towards something else beyond the here and now. It is also a mirror: our (often emotionally and morally charged) response to its existence is a lens through which we can interrogate what we as publics are allowed to feel, experience, and desire today.

In the book, I trace the various interventions the sex scene might be able to pose in a time of widespread immiseration and desensitisation. I explore the forces behind the disappearance of the sex scene; the sex scene and capitalism; the sex scene and patriarchy, and finally, the queer sex scene against representation. Below is an excerpt from the chapter on capitalism.

Revolutionary Desires: The Political Power of the Sex Scene. By Xuanlin Tham.

If culture is essential in shaping our imaginations, what lies in its immense pool of images and discourses that could be harnessed to catalyse [a] break in capitalism’s looping continuity? […] One of the most visceral ways an art form can instantaneously bring us back to sensing in our bodies (just think about the blood rush it instigates, maybe the held breath; the heightened awareness of other people in the room, the way you might begin to feel your clothes against your skin), the sex scene is, by nature, an interruption: a moment of pause in the otherwise smooth automatism of our disembodied media consumption. Where the experience of watching a film is often understood as a passive absorption, [film theorist] Linda Williams writes that “the shock of eros” decisively transforms this encounter into a “two-way street: our bodies both take in sensation and then reverse the energy of that reception”, becoming activated as what film historian Miriam Hansen describes as a “porous interface between the organism and the world.”

Many of us know that capitalism is hellish; in fact, being able to express this very sentiment has become a way of allowing ourselves to be reassimilated, frictionless, into its continued existence. [Mark] Fisher suggests this is why a moral critique of capitalism has failed to generate any significant opposition, and instead reinforced the conviction that no alternative exists. “Poverty, famine and war can be presented as an inevitable part of reality, while the hope that these forms of suffering could be eliminated easily painted as naive utopianism,” he writes. What is needed is a glitch in the surface: for the porous interface of our bodies to become receptive to the fact that ‘reality’ under capitalism remains contingent, up for grabs.

Writer and film critic Xuanlin Tham.

Recall the common refrain that sex scenes are “unnecessary”. Unnecessary for what? Does sex need to have a purpose? This idea that the sex scene should be instrumental, productive somehow, is internalised capitalism par excellence. Pleasure for pleasure’s sake has become unthinkable. Everything must have a narrowly defined purpose: it must be legible and contained within the marketable, commodifiable mechanism of plot; it must bolster capital exchange in some form, if only by permitting consumers to digest it with ease. The anxious need to disavow the pornographic seems to haunt this sentiment, too: sex for its own sake is not only valueless, but terrifying somehow, which speaks of a learned suspicion of bodily pleasure that serves capital accumulation.

During a test screening for David Cronenberg’s 1996 film Crash, an audience member fed back to the director that “a series of sex scenes is not a plot”. Cronenberg recalls in an interview: “I said, ‘Why not? Who says?’ And the answer is that it can be, but not when the sex scenes are the normal kind of sex scenes: lyrical little interludes and then on with the real movie.” A chrome-cold, erotic odyssey, Crash follows a married couple who fall in with a group of car crash fetishists seeking ever-greater sexual thrills from reenacting famous car crashes, fucking in moving or wrecked cars, colliding with each other on the roads, watching crash test footage, and ruminating on the violent fusion between flesh and metal as they pursue every possible little death – petite mort – on the precipice of the final one. Released to great controversy with a NC-17 rating, and the subject of a moral panic that led to a (mostly unsuccessful) campaign to ban its theatrical release in the UK, Crash is a visceral literalisation of the violences of late-stage capitalism and its derealising impact on our bodies and psyches. Harnessing the initial, concussive dissonance of the idea that a car crash could ignite sexual arousal, Crash pierces through the dazed automatism of mundane life, forcing the fetish object of consumerism, the automobile, to become foreign and dangerous to us once more.

“A car is not the highest of high tech,” Cronenberg says. “But it has affected us and changed us more than anything else in the last hundred years. We have incorporated it. The weird privacy in public that it gives us.” The archetypal product of industrialised capitalism, the car represents our grand retreat into privatisation: a way of life socioeconomically structured around the atomised individual. Brutally warping capital’s promise of safety, ease, happiness, and fulfilment like a sheet of metal, Crash confronts us with the distorted reflection of capitalist realism: suppressed knowledge of widespread alienation and disillusion; libido sublimated into inanimate objects, as if taking the logic of consumerism to its final, perverse extreme; an omnipresent violence waiting to puncture the surface.

Revolutionary Desires: The Political Power of the Sex Scene is available to order here.