As a mode of entertainment and engagement, cinema has escaped the usual confines of a movie theatre and become medium agnostic. To use a broader term, moving images— once showcased in slot machines and at fairground sideshows— have become integral residents of a theatrical release and television series, and are invariably deemed “cinematic”. Content released on streaming platforms like Netflix and Amazon, though, recently fought for cinematic legitimacy. When Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma (2018) bagged three Oscars from ten nominations, Steven Spielberg proposed a change in Academy rules to bar Netflix from competing. Quentin Tarantino has remarked that films made for streaming “don’t exist”. Yet, streaming has also seen champions like Criterion, which has released Netflix and Amazon titles like Roma, The Irishman (2019) and Sound Of Metal (2019) in their physical media catalogue. Tamil film legend Kamal Haasan, who faced opposition in 2013 for proposing a direct-to-home (DTH) release for his magnum opus Viswaroopam, recently declared, “I’ll perform even if you release films on a wristwatch!”

So, a fair question to pose now is- What else can be cinema? Instagram reels? YouTube videos? Vlogs? How about news broadcasts? Hot-button movies with journalistic themes like All The Presidents Men (1976) and Network (1976) are well regarded in the cinematic canon. But what about telecasts— the set of moving images dedicated to conveying a piece of information? The history of the news is not devoid of cinematic theatricality. Before immortalising himself in the world of film, Orson Welles gained notoriety in 1938 with his War Of The Worlds radio broadcast, which sent panic through the populace over false reports of an alien invasion. The moment of a visibly emotional Walter Cronkite, confirming the death of US President John F Kennedy following his shooting in 1963, has passed into journalistic legend. Christine Chubbuck’s suicide by gunshot during a 1974 live news telecast was a tragedy straight out of a movie screenplay. But what about telecasts that play with the form of a conventional news show, and go beyond the usual bells and whistles of tickers, graphics and anchors holding shouting matches with panellists?

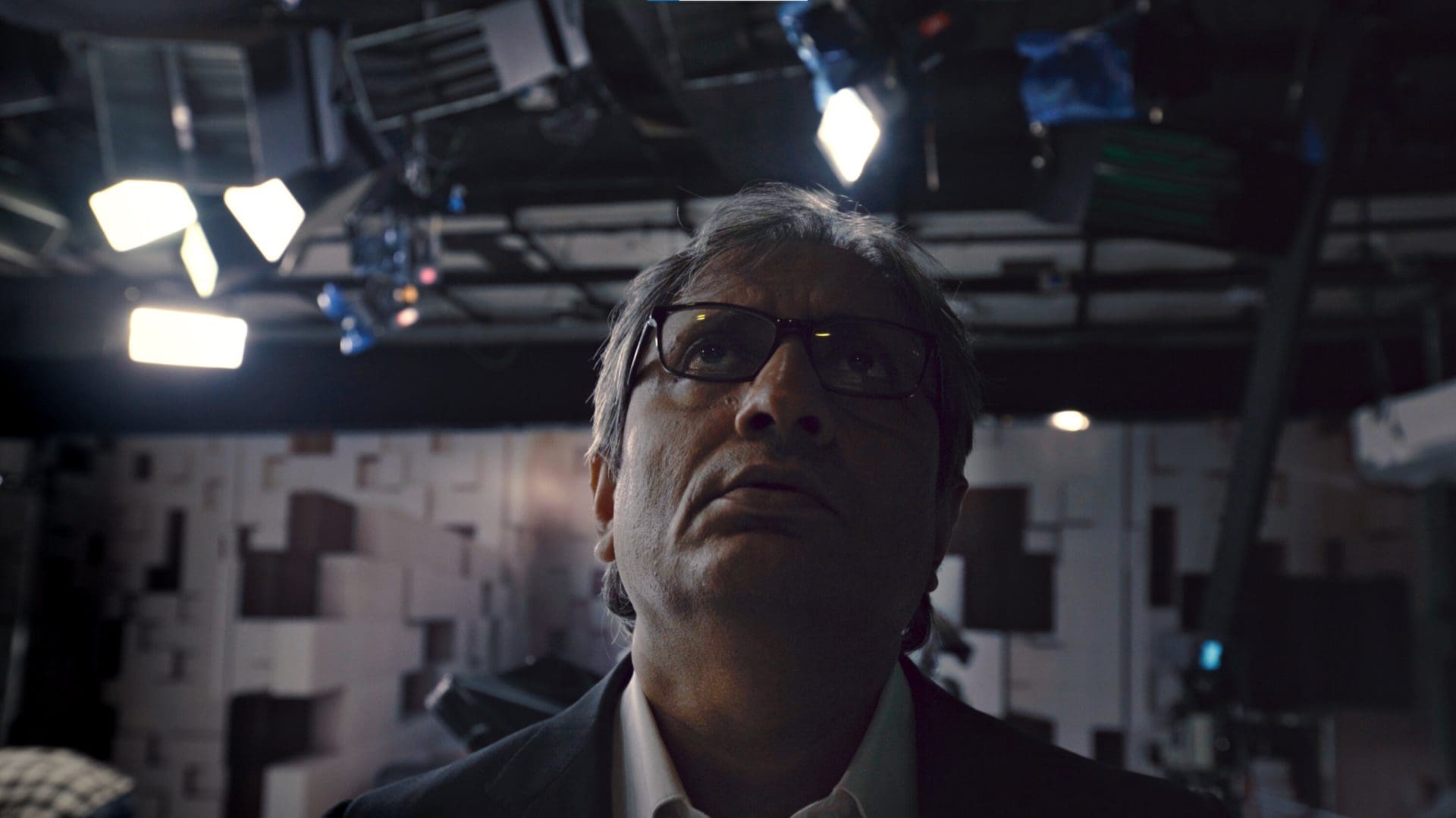

A journalist who has experimented with the said form is Ravish Kumar, the subject of the new documentary While We Watched, which opened in 40 screens across the UK. Directed by Vinay Shukla, the film follows Ravish, the editor-in-chief of NDTV India, navigating through a communally charged India— braving death threats, falling ratings, sponsorship losses and emotional hardship—to speak truth to power and bring forth core issues affecting India’s life and livelihood before the masses. With his wit, directness and lucidity in the Hindi language, Ravish has cultivated an appeal that cuts across social boundaries, while making foes for his anti-establishment stances in Narendra Modi’s India. The film also offers a glaring portrait of India’s media ecosystem, which has contributed to the increasing polarisation of opinion along communal and jingoistic lines, leaving Ravish as the lone voice of reason in a sea of propaganda-peddling media outlets.

At the film’s premiere hosted by the Docsociety in Curzon Bloomsbury, director Shukla explained why he chose Ravish as his subject: “The news would make me and my friends very anxious. It is a major system of public information and if people are cutting themselves off from it, there’s something wrong. When we started filming in 2018, many news anchors would tell their audiences they are number one and are here to serve the audience. Ravish would tell his audience that they are the problem and they need to stop watching TV!” The solitary nature of Ravish’s predicament intrigued Shukla: “I saw a protagonist who was being very vulnerable. As journalists and artists, you’re often afraid you have a lot to say, but nobody wants to listen anymore. Your art is ready, but the audience just doesn’t care. I felt Ravish was going through a moment like that. It felt like a slow-melting glacier…I wondered what drives you forward in moments when nothing changes? It is a hopeful film which helps you understand what it means to have that resilience within you to continue doing what you want to do.” On his optimism to carry on despite threats, Ravish said, “I find hope when I deliver a video or report to millions of viewers. That’s the only way you can save this profession. In India, you have many beautiful things, but there is no media. Journalism has gone for a toss. The mainstream media is to communalising innocent masses with a vengeance.” Ravish resigned from NDTV (New Delhi Television) in November 2022, following the company’s takeover by billionaire Gautam Adani, who has close links with Prime Minister Modi. He has since been running his own YouTube channel.

“Showman” is a sobriquet accorded to figures like P.T. Barnum and Raj Kapoor. Ravish lacks the pomp and pageantry of those two, but fits the description of the term in his own humble way, for he has distinguished himself in an environment noisier than a circus. While most news anchors address the audience from the comfort of their air-conditioned studios, Ravish has remained a journalist, doing exhaustive leg-work to present corners of India untouched by mainstream media. Unburdened by the pressure to become number one, he has presented unvarnished images of people, places and situations in all their grey complexities. On the eve of the 2014 general elections, Ravish toured Katara, a village within the famed city of Varanasi, which was also Prime Minister Modi’s political bastion for the polls. His report presented a village still ravaged by untouchability, a discriminatory practice of denying certain castes access to public facilities— a far cry from the romantic images of Varanasi as the colourful cradle of Hindu civilisation and culture. Rather than resorting to hard, black-and-white journalism like his contemporaries, Ravish relinquishes his pulpit to the village residents. He presents a nuanced picture of the area by interviewing its residents and gleaning from their experiences. The coverage flits between conversations with reluctant villagers, long shots of the village’s yellow-grassed vista and postcard shots of thatched huts. Bare-chested men and saree-clad women carry hefty loads of leaves and go about their business. Almost in the manner of an Italian neo-realist classic like Luchino Visconti’s La Terra Trema (1948), Ravish offers viewers in metros like Delhi a sociological portrait of areas untouched by urbanisation but infected by a social evil like untouchability.

Conversely, Ravish brings equal panache to his YouTube coverage of international cities like Bruges, Paris and London. He serves as a medium to these cities for his audience, who often hail from a spectrum of the populace that cannot afford international travel. He brings the same clarity of thought from his NDTV monologues and transposes them to voiceovers framing the shots of city streets during his early morning walks, akin to Chantal Akerman’s News From Home (1976). Poignantly, he uses the visuals of an arising London to comment on the status quo of Indian cities, emphasising on how far India is yet to travel. Near Piccadilly Circus, Ravish laments, “The streets and buses are well-maintained, as people all over the world visit here. Traffic lights here are strategically placed so that people notice them and there is no chance of jumping them. The number of people obeying traffic lights in our cities is increasing. However, we are busy renaming our roads in Delhi and claim independence from a colonial mindset. However, it does not change our actual history… We must read and understand it.” This is in reference to the establishment’s drive to rename cities and roads from their colonial origins.

Ravish had two memorable moments in 2016 while anchoring the Prime Time show at NDTV India. They persist in memory as he played with the form of the news telecast to defend the right of the media to question. In February that year, the news of leftist university students allegedly raising seditious slogans sparked an outrage in the pro-establishment media, which resorted to hyperbole in reporting the facts. To counter the toxicity of their debates on the issue—replete with bombastic graphics and screaming panellists cramping the screen— Ravish faded his screen to black and addressed his viewers on the dangers of debate television. His words appearing against the black screen, Ravish poetically indicted his contemporaries for their hyperbole: “This darkness is the state of television. Debate shows are destroying the variety of opinions in our democracy. Our job is to not challenge, intimidate, incite or threaten, but to ask tough questions. However, the questions are getting left behind and no one cares for the answers. News anchors and spokespersons are politicising the deaths of soldiers in the name of nationalism.” Metaphorically, the screen remains dark. Seven years on, debate television in India continues to languish in the dumps. It perhaps saw its lowest ebb during the pandemic, when it became a sinister breeding ground for conspiracy theories surrounding the suicide of Indian actor Sushant Singh Rajput in June 2020.

In November 2016, the government imposed a day-long ban on NDTV India for allegedly violating broadcast norms in its coverage of the Pathankot terrorist attacks. Responding to the ban, Ravish—ever the showman— brought two mimes in full makeup to the studio, positioning one as the “authority” and the other as his lackey troll. In an absurd yet brilliant piece of journalistic theatre, he poses questions to the authority figure, only to be shot down by his muscle, both of whom speak in an indiscernible tongue. The piece conveys a journalist’s frustration in attempting to reach out and question the establishment. Both positions speak in different tongues and live in different realities. It also highlights the establishment’s use of muscle over reason to engage with citizens raising questions. The mimes use pantomime to warn Ravish of his fate if he wouldn’t stop his incessant questioning—he would be eaten like a banana, diced like a kebab, or get decapitated. This innocuous skit anticipates the real-life, behind-the-scenes drama in Ravish’s life, as documented in While We Watched, where he is subject to numerous death threats. At one point, the signals of his channel mysteriously jam when they carry an expose of a murderer admitting to lynching a Muslim man on the suspicion of transporting beef.

Despite such obstacles, Ravish shows no signs of slowing down. Under constant fear of having his YouTube channel shut down, and with no publication offering him column space for his views (even as he offers “to write for free”), he powers through. “It is my job and my life. I can do nothing else,” Ravish tells me, adding, “I observe very keenly and get thousands of ideas. I see patterns and take photographs, which I upload on Instagram. My aim is to challenge the audience through my work, so that they can question and see things more clearly”.