Do we need to talk about the carpets in Priscilla? In the movie directed by Sofia Coppola, we follow Priscilla Presley around her home in Graceland—Elvis’ mansion in Memphis—as she spends her days alone in delicately decorated rooms, with soft, carpeted floors. Creme, quiet and inoffensive, the living room floors resemble a 1960s version of those white, fluffy influencer sofas of recent years. The hallway carpet depicts a large guitar and musical notes dancing across the floor. The carpets in their bedroom are completely black, matching Elvis’ state of mind and heavy doses of sleeping pills as he returns from his life as a star. Rather than grandiose, Coppola’s Graceland feels haunted by Elvis’ absent presence, always away touring, making noises, moving, elsewhere. In Priscilla, the carpets are everywhere. Soft and plush, they give off the feeling that you wouldn’t notice if something—someone—fell.

If there is a moral to the carpets in Priscilla, it has to be how they softly and innocently pad the sharp edges of their relationship, and cover the dark holes inside the main character, making everything seem calm and perfect when it isn’t. Just like the carpets, Priscilla’s character is soft and gentle because her marriage forces her to be, waiting patiently for Elvis to return from a tour and love her. Coppola dresses up Priscilla’s feelings in the textures of their time.

Yet the movie’s use of interiors as a narrative device doesn’t feel exclusive to Priscilla. Instead, following characters as they show us around their homes, is so present on the screen today that the characters’ lives almost feel like the backdrop. We are allowed to peak inside Priscilla’s makeup bag and wardrobe in a way that says just as much about her life than her infrequent interactions with her husband, in an almost Jeanne Dielman-like way, Chantal Akerman’s masterpiece from 1976 where we follow the eponymous character over three long hours, as she quietly does the bed, the dishes, turns the light on and off, and on again, with a storm simmering invisibly underneath the surface of her home. In movies and series from the past years, from Priscilla to the White Lotus, a heightened awareness of personal belongings has almost made it to its own genre, a costume drama of the home.

Before I had the chance to see Saltburn, I knew about the film through the set design. Whereas I was presented the plot with a spoiler alert (‘you have to see it first’,) I knew about the carefully curated set design, with its articles of both symbolic and aesthetic value. A friend of mine told me about her obsession with watching interviews and behind-the-scenes videos with the director Emerald Fennell explaining how the props were all meticulously chosen and curated to describe the characters and their lives. A cheap IKEA lamp and empty Diet Coke cans in front of a Flemish tapestry placed in the background of Felix’s (played by Jacob Elordi) room doesn’t just say something about the character but speaks a language of references of its own.

“This is a film about obsession with beauty – a sort of fetishisation with stuff”, Fennell explains in a video for Vanity Fair. Every little detail in the big, extravagant house becomes descriptive of the characters’ lives in a way which otherwise would disappear from the script.

The way my friend spoke about Saltburn reminded me of the consciousness of displays of Instagram’s bathroom shelves and coffee tables; the cheesy celeb visits on Architectural Digest, or ‘what’s in my bag’ of homes. It reminded me of how we access certain markers of taste and style through stalking the people we follow. While staying at the Saltburn castle, the main character Oliver, played by Barry Keoghan, does his secret research about a piece of Dutch pottery at the house, impressing everyone with his seeming knowledge in antiques. Not only does he surprise the wealthy family he’s visiting, but he brings us inside the rooms and life of the house, too. Just like we dig around to find the designer or manufacturer of some lamp of someone we follow, in order to impress someone with our knowledge—of the same lamp—later.

There is another scene where Jacob Elordi’s character Felix gives Oliver a tour around the house, pointing out everything from the corner where he accidentally fingered his cousin to windows, a broken piano, and some ‘hideous Reubens’, all of them with the same, anecdotal tone. It is a fast-paced summary of the family’s insane wealth, but also a list that easily could have been saved for some interior design magazine.. Instead of looking behind the scenes (which we tend to see on social mediathese days, anyway), what we want to see are all the curious details lurking in the linings of the film.

But stylish film sets are nothing new. From the red velvet restaurant in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo to the intellectual Parisian apartments of Jean-Luc Godard and Éric Rohmer, which long has circulated on the moodboards of stylish people. Yet the specific knowledge about carpet designs and Flemish tapestries – is that a prop of our time? Does it invite an object-obsessed culture under the skin of the screen, or is it simply a perfect marketing structure, where movies imitate our real life needs to copy our heroes—or at least their homes?

In Priscilla, the perfume Chanel N°5 appears on screen several times. First as the character’s ‘grown up scent’ as she moves in at Graceland—later on the neck of a breezy blond girl in 1970s LA who Elvis hits on in front of Priscilla. He asks her which perfume she’s wearing, when he should recognise it as the scent of his wife. Most of us know about Chanel N°5, and the symbolism of that scent, and many of us know that the director, Sofia Coppola has a long-standing relationship with the French fashion house Chanel. She started off there as an intern, and today she directs their commercials and wears their clothes. She is a Chanel woman, and so it was only natural Priscilla was, too.

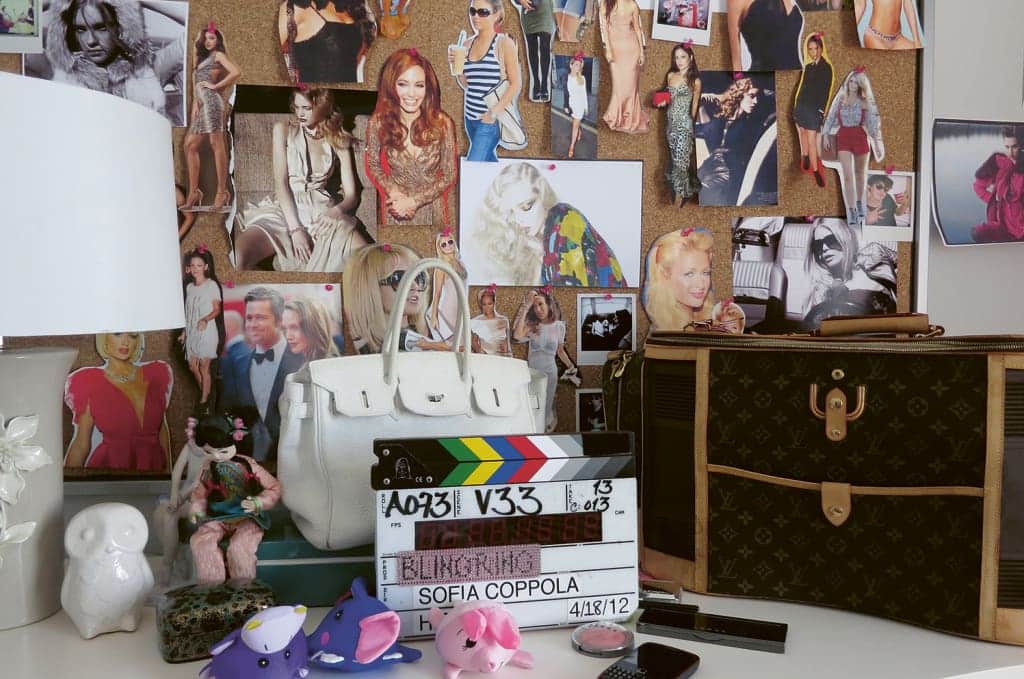

Sofia Coppola’s big pink book release has been one of the biggest publishing buzzes of the winter. The book consists of behind the scenes photos taken by Coppola herself; notebooks and mood boards and messy bathrooms and Kirsten Dunst out of focus. The book holds the stuff and the mess that existed on set but maybe only made it into the movie for a quarter of a second. From textile samples for dresses to Elvis’ pills on a silver tray, or a sketchbook illustration of how Dakota Fanning moves around the skating rink during a shot; One would think in our dark times, we would want to escape reality through movies. It seems instead we want to meet the films at their surface, see all the objects that make up their spaces, and eventually make them our own.

Featured image: Sofia Coppola, from Archive (MACK, 2023). Courtesy of the artist and MACK.