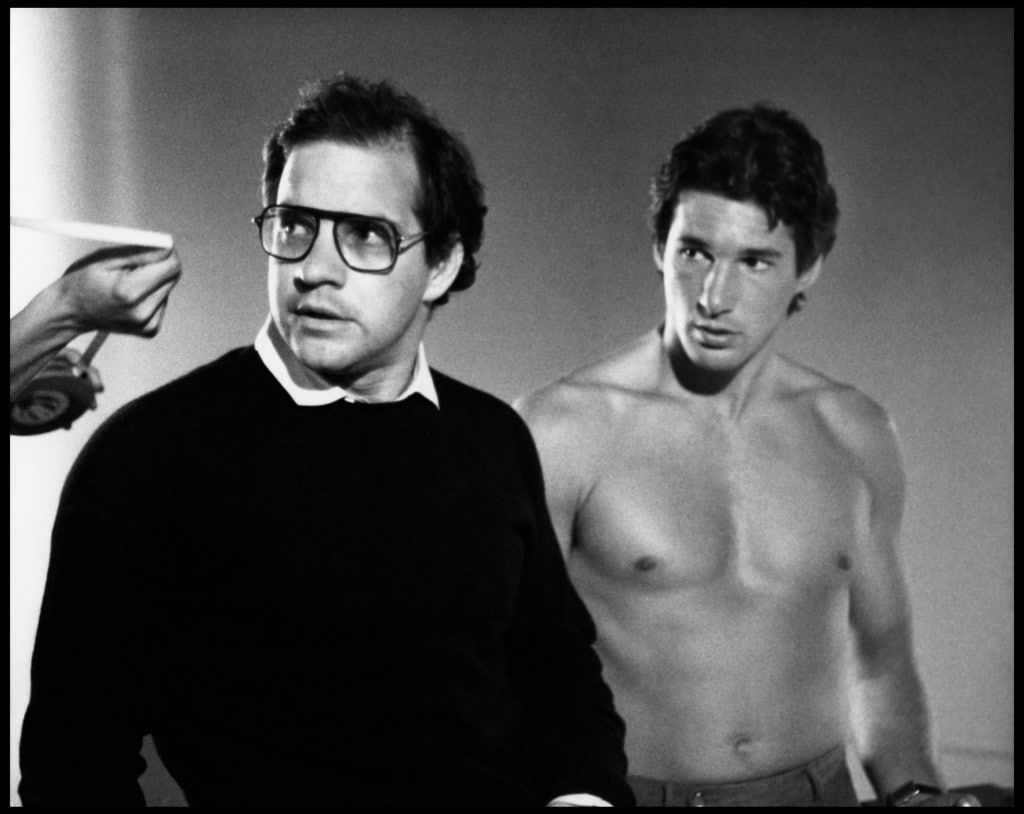

The writer-director Paul Schrader’s new film Oh, Canada is a departure from his recent, unofficial Man in a Room Trilogy, which was based on a broader theme that Schrader has depicted since he became famous for writing Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. Starring Richard Gere and Jacob Elordi, Oh, Canada is a powerhouse of trans-generational male acting talent and rather than exploring sin (as so many of Schrader’s works do) it focuses on redemption, death, and freedom. Of all the great filmmakers that emerged from New Hollywood, Schrader is foremost a storyteller, and he uncovers the dark truths of manhood—isolation, wrangling with faith or obsession—with a pragmatism that he credits to his serious religious upbringing, film education, and previous career as a critic (encouraged by the formidable Pauline Kael, no less). Even if he hasn’t directed it, there’s something singular about a Schrader script that makes the film as much his as anyone else involved. That includes Taxi Driver.

It is a career that has spanned dozens of movies. Some are masterpieces. Others, as Schrader himself is quick to point out (a credit to his reputation for strong opinions, which I can attest to being true) are interesting at best. But at least he has always found something to say, even if he is saying it through a unique voice, and anticipating a Paul Schrader film means going into the unexpected. From Blue Collar to American Gigolo, his depiction of the life of writer Yukio Mishima (Schrader has always had a connection with Japan) and more recently Master Gardener, the writer-director’s oeuvre is anything but unoriginal. As Oh, Canada premieres at Cannes Film Festival, Paul Schrader spoke with me from his home in New York about his upbringing, his writing process, and the meaning of legacy.

Kitty Grady: You’ve once said that, thanks to your Calvinist upbringing, you have an intellectual approach to film that is not emotional. Has this changed over the years?

Paul Schrader: It’s no longer exclusive. I saw myself as a theorist at a young age. As a Calvinist, the earliest breakthrough was the cinema of Ingmar Bergman and the way he deals with religious metaphors. I would see these films and think, “there are the same themes we’re learning”. Then there was the European cinema in the 1960s— one of the glorious moments—and from then, I decided to become a film critic. A film intellectual.

KG: After leaving Calvinism, you renewed your faith as a Christian later in life.

PS: The word “faith” isn’t right. I like to go to church. It allows me quiet time and meditation. I don’t know if I am a believer but I see the religious tradition as a good grounding and I would not turn my back on it. As a kid, I was quite serious. The Calvinist community I grew up in was very intellectual, and it is not an emotional religion. That’s how I was raised. So my original inclination was to become a serious film scholar until it became necessary to go into fiction.

KG: Your “Man in the Room” stories—like Taxi Driver, American Gigolo, First Reformed and the Card Counter—focus on solitary characters grappling with sin and redemption. Where did these themes come from?

PS: This is a character I’ve returned to many times, but not recently. It came from [Robert] Bresson’s existential question. It isn’t “should I die?” but “should I live?” What I started to realise in the 60s and 70s was that there was a rich tradition of this character in literature but he somehow hadn’t transitioned into film. So I decided that it was about time, and that was when I wrote Taxi Driver. When I write a “Man in the Room” story, I am not searching for anything within myself. Maybe I was at the beginning, when I was sleeping in my car, but I’m interested in the symbolic. The closer I get to my own personal story, the weaker it is. Symbolism holds more truth.

KG: And yet your first feature Hardcore featured a character based on your father, whose wish was for you to become a minister.

PS: Indeed. We filmed at my church and at my community in Grand Rapids, Michigan. I also directed Light of Day, which has a character based on my mother. And I’m disappointed with both of them. They’re not very good films, so I learned to stick with metaphors. For example, I continue to write these stories about me and my brother and then they morph into something more different, thankfully. One of them became this story of three black kids in the LA ghettos. Next, I’m making a film noir about two brothers who are in love with the same woman. It’s called Non Compos Mentis. Know what that is?

KG: No.

PS: It’s a Latin phrase for someone who is declared out of their mind. They’re crazy. It’s a story about how love can make us crazy. I find that intriguing.

CC: It’s interesting you should make a film noir today when the genre feels very associated with a certain time.

PS: Well yes, it’s essentially like German Expressionism or the French Nouvelle Vague. It means a time and a place: the US between 1945 to 1958. There were social themes introduced in the 60s. But why can’t you make a film noir today? I can do anything I want, whether it’s a comedy or a German Expressionist film.

KG: Taxi Driver feels like such a New York film. Do you feel it needs to be that time and place?

PS: I wrote Taxi Driver in Los Angeles. The only reason I set it in New York is because there is a higher volume of taxis. With American Gigolo, however, I really anticipated the zeitgeist at the time. It’s a film about superficiality. It isn’t a noir. It depicts this Neo-Edwardianism that was coming into fashion during the 80s. Richard Gere’s character around then was the Neo-Travolta from Saturday Night Fever, and I was right about that all from the start. I hit a bullseye. But one of the biggest mistakes I made was to stick to the ending of Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959) [Pickpocket also topped Schrader’s Sight and Sound list in 2022] for that film. Later, when I made Light Sleeper, I saw a better opportunity to use that ending. I was hesitant at first to do the same thing, but I said, “Fuck it! I’m going to use it again.”

KG: Many film releases have been inspired by Taxi Driver, in particular Todd Phillips’s Joker. I wonder what you made of it.

Yes, I wasn’t impressed by it, what he wanted to say, or what he did with it. There’s a much better interpretation of Taxi Driver showing in New York right now at the Gladstone Gallery. The artist Arthur Jafa remade the film’s ending scene and recast it with black actors, and I liked it a lot. People should go see that instead. Joker felt derivative.

KG: You’re obviously a masterful storyteller. Has your writing routine changed over the years?

PS: Well firstly, I’m not a real writer.

KG: A lot of audiences would consider you a real writer.

PS: Right, but I don’t write every day. That’s what real writers do. Is it completing 500 words a day? I can’t remember. I’m a binge writer. I won’t actually write until I know everything, the full story, the characters and their endings. It will be planned out in my mind before I sit down, and I’ll be able to tell you what will happen on page 75 without writing it. I’ll have all the acts outlined and then I’ll finally set to work. The writing part happens very quickly, but it can take almost a year to arrive at that point. That’s my process.

KG: One of your most transcendental films was Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, about the real- life writer Yukio Mishima.

PS: I’m looking forward to its first public screening in Tokyo this November. There was a lot of resistance to it when the film was first made. We even got death threats from the Yakuza. The production studio Toho and the Japanese right wing at the time agreed that it wouldn’t be screened in Japan, which was a huge disappointment. Tom Luddy, a producer of the film, ended up resigning his spot with the Tokyo Film Festival.

KG: Do you think it’s easier or more difficult to be a filmmaker today?

PS: Easier and harder. I would say they’re less constricted now than before. Everyone has a smartphone with a camera. People also forget that there were a lot of rules when we [Schrader and his peers] started out. But I would say that cinema has become much more prudish. It’s because the internet has bypassed the movies for sexual gratification. Back in the day, certain people would visit a cinema if they heard movies had sex scenes because that was the only easy place to find it. It was exciting. Now there’s not a market for it. That’s fine. Nobody goes to the cinema to see naked people anymore.

KG: Can you tell me about Oh! Canada, your latest feature? Why adapt the late Russell Banks’s novel?

PS: Russell [Banks] was a good friend. I was emotionally attached to him. He had written this book about dying when he was healthy, and then he was dying in the same way he’d researched for his book. I realised that I had to make a film about dying, as it was on my mind. I’m not getting any younger. The name is related to the Canadian anthem but it’s another metaphor. It represents possibility, freedom, and death. It was a reflection of Russell.

KG: I wonder if it’s also a reflection of yourself. As you enter another phase of your life, do you think about things like legacies?

PS: Of course. I ask myself, “How many films do I have left in me?” and “Is there something I must say?” With each film, I consider how it might seem as the final film. First Reform was a good “last film” for me, but then so was Master Gardener, and I’m sure Oh! Canada is the same. Regardless of which one will be the “last film”, I will continue telling serious stories. All of my life I’ve lived as a serious person; serious about books, plays, ideas… I was raised that way. It’s an obligation of mine. You don’t want to live your life compromising on a piece of junk.

Main image: Paul Schrader standing in front of the Japanese poster for his film Mishisma: A Life in Four Chapters (1985).