When you see them cheering on screen, that’s when the dread will start sinking to the pit of your stomach. It’s around a few hours into Christopher Nolan’s monumental biopic on the life of Robert J. Oppenheimer, and the scientist’s newly created atomic bomb has just successfully blown a crater in the middle of the New Mexico desert. The people are celebrating, but we, and Nolan, and, in a sense, even Oppenheimer himself, know better.

From its very first shot, Oppenheimer is haunted by the myth of Prometheus—a mortal who stole fire from the Gods to give to his fellow man, and received an eternity of torture as his reward. Ironically, it’s in this moment of earnest celebration, as the titular physicist and his peers revel in the knowledge that they have managed to weaponise a power that was never meant to be theirs, that the tragedy of Prometheus feels most apt for comparison. They’ve succeeded in playing God—but for their blasphemy, there’ll be consequences.

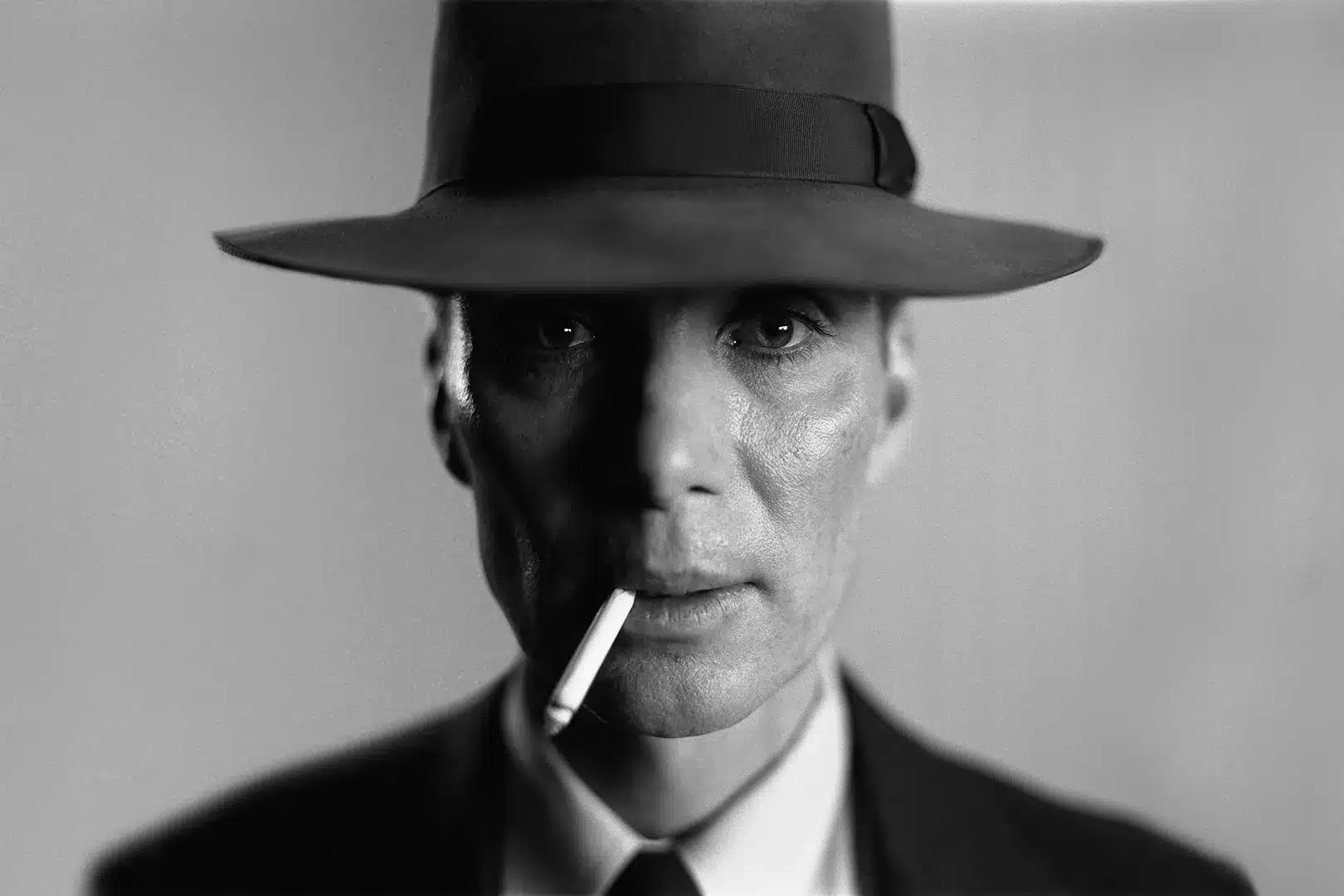

This is where Oppenheimer kicks into another gear, and brings a cathartic moment of scientific revelation back to ground zero with a devastating tremor. As he watches the terrifying miracle unfold, Cillian Murphy’s titular physicist utters eight of the most infamous words ever to escape a person’s tongue: “I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” It’s a chilling line with delivery powerful enough to silence the bomb itself, if just for a moment. Up until this point Nolan has kept any extravagant displays of filmmaking close to his chest, the first half of the film being much more concerned with charting Oppenheimer’s journey from charismatic young professor to destruction incarnate, following the prodigy as he’s enlisted to help build a nuclear bomb for the US government in an effort to beat Germany and then Russia in the arms race.

It admittedly takes some mental gymnastics to keep up with Oppenheimer’s busy first half, which throws a daunting amount of names, characters and science jargon at you at dizzying speeds, but by the time you reach the whirlwind final act you’ll be glad Nolan took the time to pad you out with the essentials. We meet US Lieutenant Leslie Groves (Matt Damon), a gruff but intelligent Army engineer overseeing The Manhattan Project; Communist party member Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), who would for a time be Oppenheimer’s mistress; Oppenheimer’s devoted wife Kitty (Emily Blunt), and physicist and eventual father of the Hydrogen bomb Edward Teller, played with a thick Hungarian accent by none other than Benny Safdie. It’s a star-studded cast, for better or worse, with some of them looking right at home in Nolan’s portrait of 40s/50s America (Tom Conti, Gary Oldman, James Clarke), and others clumsily shoe-horned in for the sake of an eye-grabbing ensemble (Rami Malik, Josh Peck). It’s a joy, however, to watch Robert Downey Jr. as slippery Atomic Energy committee chairman Lewis Strauss. After running around in an Iron suit for over a decade, Downey Jr. just seems happy to have a meaty new role to tuck into.

The spoils, though, were always going to belong to Cillian Murphy, whose turn as Oppenheimer makes you wonder why he isn’t cast as the leading man more often. Between his understated but intense performance and Nolan’s writing, they touch on faucets of the theoretical physicist’s persona that often get lost under the weight of his complicated legacy; his charm, his rebelliousness, not to mention his reputation as a notorious womaniser. Nolan has never been one to deliver great romances to the screen, but Cillian does a fine job carrying the slack with a few wry smiles and a flicker of his piercing blue eyes. As it turns out, Oppenheimer got game! And Murphy makes it look effortless.

Of greater importance is how Nolan and Murphy communicate the political and moral tug of war raging inside Oppenheimer throughout the film, from his early brushes with the Communist party—whom his association with makes up the formative third act, seeing him brought to trial on the accusation of being a Soviet spy—to the guilt he feels at the hundreds of thousands of deaths on his hands post-Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Nolan and Murphy put multitudes into Oppenheimer, and as you navigate his cavern of conflict and contradiction with them, multitudes will emerge from you in response.

After sci-fi puzzle-box Tenet failed to leave much of a mark, it’s refreshing to see Nolan once again injecting his otherworldly sensibilities into Historical events, and the story of the scientist who became death and the complex legacy he left behind seems ideal for the themes Nolan has been obsessed with since Memento: time, space, memory, obsession, the destructive ego of men. What’s beginning to feel stale, though, is the predictable framework that the filmmaker seems to return to again and again. The non-linear structure; how blatantly he prepares his audience in the first two acts for the grand unravelling in the final third. You can’t blame him—these are marks of his authorship, and he’s found a winning formula, after all. He’s the wizard of his own carefully constructed cinematic worlds, but even as he dazzles you with big reveals, and dazzles he does, there’s a festering desire for the filmmaker to learn a few new tricks and really surprise us with his next feature.

On the other hand, we might be better off not trying to fix what simply isn’t broken, and as monotonous as Nolan’s approach feels at times, there’s no denying that it works a charm on a fresh audience. Oppenheimer is at its strongest in its second half, when the director begins laying his cards on the table one by one, unveiling a royal flush of narrative twists and turns. These sequences are helped along by a sensational score by Ludwig Görranson, who makes a Greek Epic out of a courtroom full of suits. Görranson’s work in the film is essential to the sheer scale that Nolan wants to communicate with this story, and the score supports the film with a thunderous power in a way not dissimilar to Phillip Glass’ iconic work on Koyaanisqatsi. It’s a credit to Nolan that he knows when to let the pounding score settle into silence and allow the equally accomplished sound design team to work some magic of their own—their phenomenal communication of the destructive power of the bomb may well make for your most memorable experience in the cinema this year.

Is Oppenheimer Christopher Nolan’s best film ever? Despite the growing consensus, I don’t think so. Perhaps it’s missing the re-watchability of Interstellar, Inception, The Dark Knight, and The Prestige; films that you can tune in to at any point in their runtime and be swept up in the big ideas and thrills of their worlds. But this harrowing portrait of one of the most important men to ever live does slide into his oeuvre comfortably. Maybe too comfortably, but it does so with the balance of flair and depth that we’ve come to expect from the auteur, and is exactly the kind of film we’ve been sorely missing over the last handful of years: a big budget blockbuster that dares to asks its audience to challenge themselves and engage if they want to keep up. Oppenheimer may or may not end up being Nolan’s magnum opus, but, at the very least, we can all thank him for that.