When asked about contributing to this first edition of A Rabbit’s Foot on French cinema, it was already clear in my mind that the subject would be François Truffaut.

Not only because the French director has been at the centre of my ongoing project as a director, but also because he is the man who made me understand that films are not just mass entertainment, but also an inherent part of our culture.

Truffaut is the most famous French director in the world, and I am quite certain that everybody has seen at least one Truffaut film in his life: most reasonably The 400 Blows.

Still, as a Truffaut and New Wave admirer, I would call myself a “late bloomer.” Like many young cinephiles of my generation growing up in the 80’s, the film was an escapist adventure, a source of bewilderment and awe. My heroes were John Carpenter and Steven Spielberg. I wrongly thought Truffaut and his peers belonged to an “old school” of French filmmaking.

But one film by Truffaut changed my opinion completely: Fahrenheit 451. Fahrenheit 451 is a science fiction film, a genre that I had always revered. And the film became a cult favourite of mine until I realised later it was directed by the same man who had made Day for Night. I recently discovered an interview with Nicolas Roeg, director, and former director of photography, who shared his experience as a cinematographer on Fahrenheit 451:

“I’ve always felt that, although Truffaut was greatly revered and admired, at the same time, in terms of film and how much he loved film, he was underestimated. Because he was known to be a literary man, someone who was enormously fond of literature, he was adopted by a very literary set. But in fact, his love of literature was separate from his love of film. I think that’s why, many times, he has been underestimated as an essentially visual person. I enjoyed working with him tremendously on Fahrenheit 451, which was a film very much to be ‘read’ in terms of images. I suppose he was the first director, the first film person, with whom I’d enjoyed having a conversation about film, or the hope of film. There weren’t many in those days.”

Nicholas Roeg has a point: Truffaut is one of the few artists whose passion for his medium constantly inspired his creative work. Today, film culture seems to be delegated to what people call “Classroom stuff”. We live in a material world where box office numbers and zeitgeist have overthrown the idea that a visual and film culture are at the core of any director’s work.

Of course, I know many directors who still value the idea of film culture, of what French have called “cinephilia”. But what seemed to be an essential tool for filmmakers has now turned into eccentricity.

My love for films, as a form of escapist entertainment, came to an end when I discovered as a teenager Truffaut’s book of interviews with Alfred Hitchcock, Le cinema selon Hitchcock. Reading these 250 pages of conversations about filmmaking was not only a revelation but a personal turning point. It made me understand that there was a logic behind images, and a science in how to create them. Filmmaking became something I could suddenly grasp and make mine. I felt the need to become a filmmaker.

Truffaut’s position in this classic interview as Hitchcock’s interviewer is not that of a journalist. When he meets Hitchcock, he is no longer a critic, but a director with a solid reputation, who still wants to know more about his craft. One of the reasons I decided to join the ranks of Cahiers du Cinéma in the late 80’s was the sole ambition of becoming a “director amongst directors” as well.

There have been many clichés written about the French New Wave, as well as misunderstandings about the importance of its contribution to film. French New Wave is to cinema what Impressionism was to painting: a defining moment when technique allowed artists to take a new path, invent new forms and change the shape of their discipline.

Today, I meet young filmmakers or cinephiles, who champion action films or celebrate “1970’s New Hollywood cinema” by Martin Scorsese, Brian De Palma, or Bob Rafelson. They often regard New Wave films with a sort of disdain, and even contempt. But they should know that the films they worship would never exist without the groundbreaking efforts of Eric Rohmer, Jean-Luc Godard, and Truffaut.

People tend to forget that Bonnie and Clyde, the 1967 Arthur Penn classic which triggered “The new Hollywood” was originally written for Truffaut. He passed the project but suggested it to Godard, who also passed. But I am sure that Godard’s Pierrot le Fou, released two years before Bonnie and Clyde, was inspired by the script, and then inspired the Arthur Penn film. John Woo’s favourite film is Jules and Jim while most of Wes Anderson’s work pays regular homage to Truffaut.

Truffaut’s films may look charming and romantic on their surface, but he was as much of a rebel as Godard. His rebellion took a different form. He was the producer of his movies, maintaining an independence within the French film industry. I call him a “saboteur”: he was pretending to please the industry’s demands while going for rather radical films. Here are a few examples: Day for Night, which won an Academy Award for best Foreign film in 1973, has the shape of a documentary, and nevertheless feels totally “scripted’. The structure of Shoot the Piano Player, which has an almost 20 minute flashback at the core of its story, is perhaps even more extreme than Breathless. His 1969 black and white Wild Child is closer to Robert Bresson and Werner Herzog than any other French films made that year.

Nicolas Roeg seems to concur, in his interview from the Winter 1984/85 issue of Sight & Sound:“François thought the stranglehold of the written word was going to be equalled, if not superseded, by the idea of images. I guess it takes a long time; he thought it was coming quicker. (…) For instance, he wanted no written signs, and in the fire station there was nothing written. It was very difficult to work those signs out. But think about how road signs have changed. Once when you drove down the road you’d have to read dozens of things – road bears to the left, school ahead – but now they’re just children with a stripe through them, so we can drive anywhere in Europe.

I’d hate it to be forgotten just how much of that kind of a filmmaker he was. Not just charming stories and enchanting acting. All these things were missed by the very people who had revered him as a literary filmmaker.”

Truffaut was a maverick with an education, a rebel with a cause. His background, his disarray as a child, his loneliness and longing for love and affection, are part of his work as a director. But it also should be mentioned that his terrific knowledge of cinema, his passion for films was not that of a “film freak”. Films nurtured his work and even brought solutions to his directing style. It’s clear that the Hitchcock style was a definite influence on one of his best films, Soft Skin, where every frame is composed and edited with extreme precision.

What I admired the most about Truffaut, something that moves me beyond words is his need to watch and discover movies related to his need to build a family. Making movies allowed him to establish personal, friendly relationships with other directors around the world, no matter if his endeavours were not always commercial successes.

Truffaut taught us not only to love films, but to entertain a sort of constant relationship with them. I often refer to the films I admire as “friends”: they help me; they listen to me, and I interact with them when I feel discouraged or uninspired.

But after all, isn’t it why we all want to “make” things, so that they allow us to build a sort of community, a shared world of works we love and cherish? This last sentence is, I know, both naïve and very remote from the realities of the contemporary film industry. “Business is a ruthless business my dear” says Charles Chaplin in one of Truffaut’s favourite films, Monsieur Verdoux.

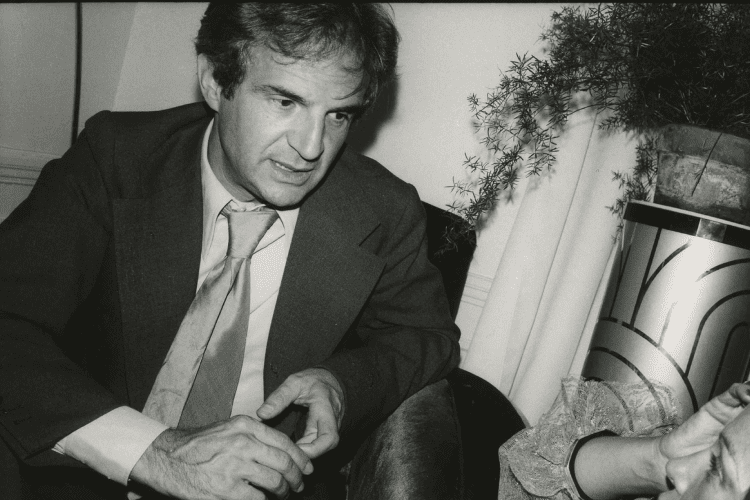

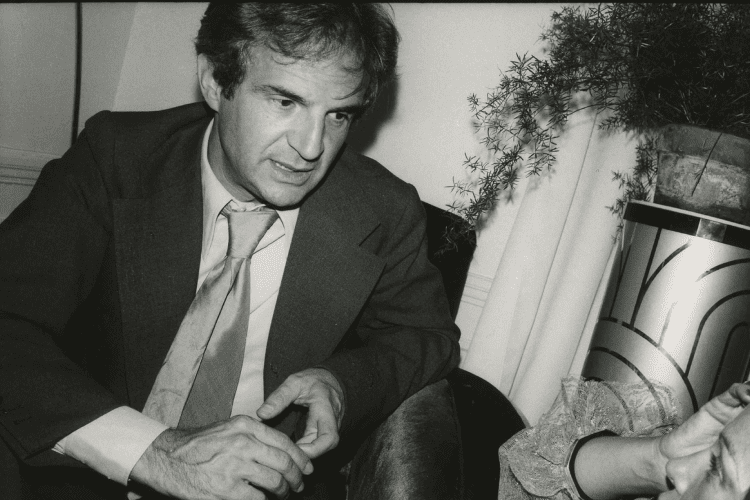

I met Truffaut only once, when I was a teenager, accidentally in a shopping mall, in Paris. I was so impressed when I recognized his face, that the only word I managed to utter was: “Are you François Truffaut?” To which he replied “I am.”

I did not want to bother him, thinking that there would be one day another occasion to meet him, and perhaps talk with him. It never happened, and since that brief encounter, I have maintained an imaginary conversation with him.

Godard once wrote about Truffaut:

“Our grief would speak, speak, and speak, but our suffering remained cinematic, that is, muted. François may be dead. I may be alive. There is no difference, is there?”

There is a difference; of course. Truffaut’s loss to cinema is immense and nothing will comfort us from this sorrow. But his films remain, as well as his work as a writer.

Let’s give him the last word, while listening to Georges Delerue’s soundtrack for Day for Night: “Throughout our lives we become different and successive people, and that is what makes our personal recollections so uncanny. The final person struggles to bring all these previous characters together. The worst thing is the rereading of emotional letters. You find that you spend your life beating yourself up, out of proportion, instead of doing yourself good.”

– François Truffaut