With over 500 film scores and sales of over 70 million records, Ennio Morricone was a giant of music. Ae documentary which premiered at Venice last year had glowing testimonies from scores of contributors, including Bruce Springsteen and Clint Eastwood, The Mission director Roland Joffe, Asian auteur Wong Kar Wai, Metallica guitarist James Hetfield and, of course, Quentin Tarantino. They all agreed that Morricone was a genius. Everyone agreed except Ennio Morricone, who appeared to have despised his own art.

It’s rather painful to watch. Two and half hours of sublime music, thrilling clips and venerable talking heads, all punctuated by an elderly composer looking back with something less-than-fondness on what is surely one of the great artistic careers.

Morricone died in July 2020 at the age of 91, plunging Italy into a state of national mourning, a grief deepened by the continued grip of the pandemic. It was somewhat remarkable, therefore, that just a few weeks later, the Venice Film Festival managed to be the only major arts event to take place, almost in the whole world. That extraordinary edition opened with Morricone’s son Andrea conducting an intimate yet socially-distanced Roma Sinfonietta orchestra, reprising Deborah’s Theme from Once Upon a Time in America and bringing the entire, masked audience in the Sala Grande to tears, as well as the TV audience watching live. “Arrivederci Maestro” was the headline on the front page of all the Italian papers the next day.

One of the reasons for that edition of the festival going ahead, against all the odds and with a huge effort—its artistic director Alberto Barbara confessed to me—was so that they could pay special tribute to Morricone. Ennio, the son of a jobbing trumpeter, actually wanted to be a doctor but his father made him study the trumpet “so he would always be able to eat,” as family legend has it. But as soon as he began playing, it’s as if music awakened something in the young Ennio and it was clear he had a gift beyond that of his father. The brassy influence of the trumpet remains clear throughout his work, part of that distinctive mix of sounds that typify his most recognisable film scores. However, perhaps because of his father’s gigging career of weddings and dance-halls, the family insisted Ennio became a classical musician and he was sent to study under the strict tutelage of composer Goffredo Petrassi, a relationship which would have great influence on him, and not always a positive one. While Morricone’s career seems to have flourished in what one would traditionally call a non-classical realm, it appears he struggled all his life to prove himself to his peers and draconian tutor at the conservatory—and to himself. Perhaps it’s Italian guilt, but there’s something very sad in watching the elderly Morricone look back on his career and say things such as: “I’m a traitor to the purity of the composer.”

In this documentary, simply called Ennio—like he’s a one-person name now, like Prince or Madonna—and directed by Giuseppe Tornatore, there’s a clip from a TV interview in black and white in which the venerable Petrassi himself is asked for his thoughts on music written for the cinema. He calls it “prostitution.” Petrassi had one miserable experience of working for films, being hired (and then fired) from composing the score for John Huston’s Rome-shot production of The Bible. The man who replaced him? Ennio Morricone, who felt terrible about replacing his teacher and could not even bring himself to complete the job.

So, no, Ennio never felt he was up there with Chopin or Mozart or Bach. Yet his melodies have entered the lexicon of both music and movie, creating themes and melodies that are soaring, familiar, hummable, whistleable. Metallica, for example, have opened all their gigs since 1983 with The Ecstasy of Gold from The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

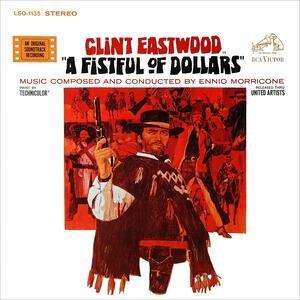

While Morricone’s early career boomed in the early 1960s, he was working for RCA Italy and arranging pop hits such as enduring classic Il Mondo for Jimmy Fontana and Gianni Morandi successes, including In Ginocchio Da Te and Non Sonno Digno di Te. He also worked with Italian legend Mina on many of her most florid hits. Most Italians can still sing every word of these songs, hum every note. But it was pop music, not classical, and nothing to do with movies. Ultimately it was an old school friend who lured him to the screen, a kid called Sergio Leone who wanted to find new ways to shoot his favourite genre, the Western. Leone allowed Morricone to use his whole head of sounds, to open up his full creativity on A Fistful of Dollars in 1964. For the classically-trained arranger in Morricone it was a chance to experiment, with bold use of sound and instrumentation, employing layers of whips, anvils, bells and, of course, that famous whistle by Alessandro Alessandroni.

Audiences experienced something akin to ‘culture shock’ on hearing these sounds applied to the Western landscape, giving the American mythology of the genre an alien, other-worldly aura. As Clint Eastwood has fondly recalled with wry humour: “That music helped dramatise me. Which is hard to do…”

The collaborations between Leone and Morricone remain among the most distinctive in all cinema, the twang of guitar strings, the mariachi trumpet trills, the coyote howl of The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, flourishing to full beauty in the score of Once Upon A Time in the West (1968), in which the music practically tells the story during an almost dialogue free, 20-minute prologue. Their skills combined again, years later in the brilliant Once Upon A Time in America (1984).

One of Morricone’s grandest successes came with the 1987 Cannes-winning film The Mission, directed by Roland Joffe and starring Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons. Morricone’s amazing score, combining ethnic South American sounds, ecclesiastical arrangements and incantations, was clear favourite at the Academy Awards the following year, but he lost out to Herbie Hancock (for one of my own favourite films, Round Midnight) in which the music is wonderful but much of it consisted of existing jazz standards. The shock of defeat made Morricone vow never to compose for movies again.

“Round Midnight shouldn’t have even been in that category,” Joffe remarks to me now. “It really was a shock and I think Ennio was mortally offended. Although, it must be said, Ennio was quite easily offended.” There’s an example that Oliver Stone tells about his 1997 film U-Turn. When the maestro delivered his first score to the director, Stone asked him “for something more along the lines of” the Spaghetti Western sounds of his early successes. Horrified at being asked to go over old ground, Morricone u-turned out of LA and flew straight back to Italy.

As Joffe tells me: “Oh you had to know how to work with Ennio. He didn’t want to write The Mission. When he first saw the film, we showed it to him without music and I found him slumped in his seat, crying. He told me it didn’t need any music, that he couldn’t add anything to it and anything he would write would ruin the film. And he just got in a car and left.”

It would be years before Morricone received Academy recognition, championed by Quentin Tarantino who persuaded him to compose the score for his own Western, The Hateful Eight in 2016. Let’s be honest, that film is neither of these artists’ best work. But who would begrudge Ennio his limelight? Curiously, the Oscar recognition was hugely important to him, as if giving him some affirmation, some pat-on-the-back that, even if he wasn’t Bach, he may have done all right after all.

Tornatore’s documentary is long and very thorough. It’s hardly a great cinematic piece of doc-making in itself, but it doesn’t need to be: the hundreds of clips set to this wonderful music lift you out your seat with emotion, with excitement, and to make a note of a film you’d forgotten or didn’t know was an Ennio score, or which you never even knew about: The Sicilian Clan, with Jean Gabin and Alain Delon, Sergio Corbucci’s The Great Silence and an amazing-looking film called Queimada, from Gill0 Pontecorvo, best-known for The Battle of Algiers, on which Morricone also worked.

He scored 21 films in 1969 alone—these are figures more comparable to the Capocannoniere (the leading goal scorer in Serie A) than any composer. “He could come up with a score so fast it was like he was writing a letter,” Leone said. In Tornatore’s film, Morricone sighs wistfully about his gift for melody, as if it was some kind of a curse. The late Bernardo Bertolucci, for whose film 1900 Morricone scored, says that: “Ennio moves inside the music and his talent gushes out. He can’t help it,” while composer Hans Zimmer claims it’s impossible to understand or study how Morricone achieves his emotional impact. “You have to abandon critical, analytical thought and just let go,” he says.

So maybe it’s this mystical element that so endures, the impossible to identify element that lifts Morricone’s music into a realm of its own, at once classical yet so modern as to be entwined with the very grammar of cinema. For example, one can’t imagine Tornatore’s own collaboration with Ennio, Cinema Paradiso, without that wonderful theme music, a melody which of course accompanies a montage of screen kisses. Morricone’s music becomes part of the fabric of film, as vital and expressive as light, as image, as dialogue—indeed, quite often more so than dialogue.

You may have been lucky enough to see Morricone in action, as I was once, at Taormina, when he conducted an orchestra through many of his best-known scores while Mount Etna sparked in the background. It’s one of the most amazing moments in my film-watching career, but Ennio became an industry himself, conducting with huge orchestras in spectacular venues around the world for big crowds. These large productions became staples of the European summer, Morricone working as hard and as dedicated as ever, touring and playing his music, sometimes with the film clips playing on big screens. sometimes with large choirs. Modest he might seem, and diminutive and unassuming, but he had a real flair for grand spectacle.

Roland Joffe has a good theory. “I think his generation of Italians was imbued with suffering from the War and they saw great poverty and if you combine that with religious upbringing, these things stay in the soul,” he says. “Ennio had a firm understanding of hard work and peasant life so whenever he could identify with a human’s struggle on the screen, and work in themes of redemption, that’s when I think he was moved to be at this best.”

And I think this need to be accepted and recognised by his classical peers haunted Morricone as much as it inspired a prolific work ethic in composing and conducting. “He would always tell me his film work was secondary to his classical work,” says Joffe. “Time and again I would try to protest and I still can’t say I agree with him, but it obviously was his firm belief and I do sort of understand what he meant when he said it.”

One of Morricone’s most popular hits was Se Telefonando, written for Mina in 1966, a rhythmically dazzling piece of pop, with complicated brass arrangements and tonal progressions throughout, yet instantly catchy. The tune, again recognised today by almost every Italian, famously came to him while he was in a queue at the post office, waiting to pay the gas bill. I don’t suppose that ever happened to Bach.

Cinema, however, is the 20th century’s defining art form. And no other composer, perhaps no other single artist, even director, has quite captured and explored that artistic tension between modernism and classicism, between the trivial and the sublime, in the way that Morricone discovered as he explored and expressed this relationship between the music inside him and the movies in front of him. Bravo, Maestro.