“They don’t make them like they used to”. We’ve all said it. We live in a time of disposable “content” where every movie pitch is followed by the question, “have you thought about doing it as a series”. The absence of few directors can be held responsible for that feeling more than Mike Nichols. His films provided audiences with iconic performances, thoughtful scripts and impeccable taste. Candice Bergen described Nichols: “He always lived like a prince. I don’t know where that came from. But he was more princely than anyone I ever knew.”

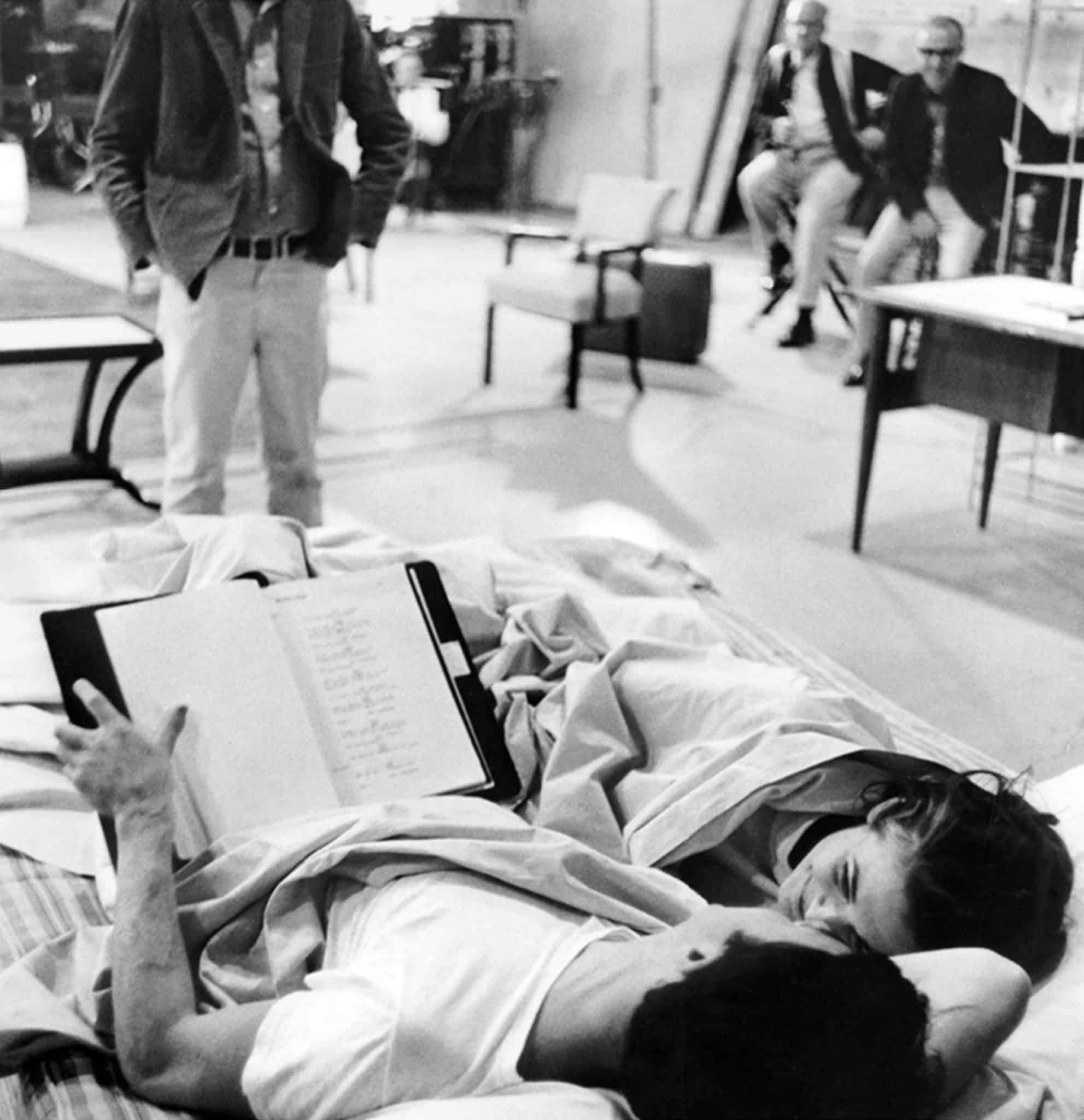

In taking a look at the career of this inspiring filmmaker, it is particularly striking how certain repetitive themes and ideas resonate throughout. In a 1986 interview with the Washington Post, the director said, “I’m interested in things that happen to men and women, centred around a bed. That seems to be a theme. But I don’t know how to narrow it down any more”. So it is that his films often dealt with the emotional and physical relationships between people, personal and epic.

Particularly interesting to compare and contrast are Nichols’s first and penultimate films. The first was an adaptation of Edward Albee’s iconic stage play Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, and his penultimate film, Closer, was based on Patrick Marber’s hit play. Nichols’s biographer, Mark Harris, described the decision to do Closer as “an elegantly symmetrical conclusion to Nichols’s filmmaking career”. As stated above, both are based on hugely successful stage plays; both were four-handers and, according to Harris, “focused on gamesmanship and jealousy”. One announced Nichols to film audiences and the other reminded them that he was still a force to be reckoned with, at 73.

By the time of the opportunity for Nichols to direct Edward Albee’s play for the screen, he was already a name on Broadway. An Evening with Nichols and May, a kind of sketch show alongside Elaine May, was a hit and they appeared on television for some time. They got to a point of needing time apart and once that decision was made Nichols turned to directing theatre. This initially led to a very successful collaboration with Neil Simon and a young Robert Redford, Barefoot in the Park. Nichols quickly gained a reputation as a generous collaborator with great taste and a good sense for what audiences wanted.

Taylor and Burton by this time had become a much greater tabloid prospect than the success of any film could really overcome. It didn’t help that while frequently collaborating they were mostly making stone cold flops. Burton knew Nichols but it was Taylor that was most keen to get the young director on board. The studio was reluctant at first to put a rookie director in with the fiery duo. Eventually they decided that Taylor would be much easier to handle if she were the man. The actress would go on to win an Academy Award for her performance.

One particular issue repeated again and again throughout Nichols’ filmography is the revelations of infidelity and dishonesty. In Virginia Woolf, as Martha and Nick reveal their attempted infidelity to the audience, Nick’s wife, Honey, is left half asleep on the bathroom floor. She is hiding from everyone, not least George who has just told her a tragic story about his son. A story that is completely untrue but represents an attack on his wife. In Closer, Clive Owen’s Larry suspects his partner, Anna, is leaving him because she has dressed after having a bath. Why isn’t she in pyjamas or a dressing gown? As his fear lingers in the air, Larry prepares himself to have a shower, all the while telling her about his business trip. As the sequence progresses we realise they have both been unfaithful and are both trying to wash away their guilt. Nichols described watching this scene on stage for the first time: “I actually got physically sick; it was so shocking and involving”.

Virginia Woolf and Closer also sit apart from the rest of Nichols’s filmography as perhaps his nastiest films. (Nichols followed Closer with the light hearted Spamalot, the hugely popular Monty Python stage musical. Similarly Virginia Woolf was followed by a Neil Simon comedy.) Both films are about people falling in love, or having fallen in love, dealing with their lowest moments but both films do offer some sense of optimism. As further disturbing elements of George and Martha’s fantasies become clear, so too does their love for each other, their need to be with each other. This was something Nichols felt was particularly important at the centre of the film and something he fought for after reading the studio’s first draft of the adaptation. For Closer, Nichols was actually thought to be relieved that he was forced into reshooting the ending from something very bleak to only mildly depressing and it did include an optimistic conclusion for Larry and Anna at least.

The cold, edgy, Britishness of Closer was rather outside much of Nichols’s filmography but maybe not if we look to the stage and a film he never made a film adaptation of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal. Betrayal and Closer both “explored infidelity as a shatteringly destructive force”. The genius of Pinter’s play is in the telling, from the end to the beginning. Having collaborated on the Broadway premiere of Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing, Jeremy Irons was going to star but Nichols’ version was never made. There was a happy ending though. Irons did eventually star in the film version directed by Hugh Jones in 1983 and Nichols did eventually direct a stage version of Pinter’s masterpiece. His version starring Daniel Craig and Rachel Weisz was a divisive production but did show he still had a certain taste for the flair of big stars and great writing.

Similar domestic scenes to those in these films appear in many of Nichols’s films. In The Graduate, when Benjamin first goes into the hotel room in which he will begin his affair with Mrs Robinson the first thing he does is turn on the light in the bathroom to create ambience. The pivotal moment of relationship breakdown in Carnal Knowledge between Jack Nicholson and Ann Margaret takes place in the bedroom, Nicholson comes and goes in and out of the bathroom. Most illustrative of all, Charlie Wilson’s War, rather than a traditional post coital bed scene between Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts, Nichols does something familiar but wholly original. It’s tough to imagine another filmmaker mounting such an intimate scene that has such epic, and tragic, consequences. Hanks lounges in the tub while Roberts fixes her eyelashes as they discuss getting anti tank weapons for Afghan rebels to fight the Russians. Typical Nichols.

Nichols’s second film, The Graduate, was recognised as a brilliant film on release, it encapsulated what it felt like to be part of a generation that had new feelings of isolation and confusion. It was, as Tom Hanks once described, a “seminal event in the history of our country”. Dustin Hoffman gave an extraordinary performance as Benjamin Braddock, a suburban wasp with no direction and no clue what life had in store. The film made Hoffman a star and Nichols was cemented as a top director in Hollywood, he won his one and only Oscar for directing the film.

It was really in The Graduate that we can find all the best of Mike Nichols, most obviously with the Casting. Hoffman, speaking at Nichols’s AFI Celebration, told the story of his own reservations about playing Braddock, who was a “track star, head of debating club, he’s from Boston, he’s a wasp”. Essentially Hoffman felt his Jewishness would get in the way to which Nichols responded, “maybe he’s Jewish inside”. He saw in Hoffman a future star with all the qualities he needed to reflect a generation. Nichols could always see through such obstacles and almost always found exactly the right, often surprising, actor. Nichols saw a vulnerability that was missing from his contemporaries, including Robert Redford and Harrison Ford who both read for the part. (Another major piece of casting that people found strange at the time was Melanie Griffith in Working Girl, Nichols threatened to drop out if she wasn’t given the role. In the end he needed Harrison Ford and Sigourney Weaver to come on board to allay studio fears.)

Perhaps an even better example of Nichols’ conviction to get the cast right comes from the story of how journeyman Murray Hamilton ended up being cast. Originally Nichols cast a relatively unknown stage actor, who happened to be a close friend of Hoffman, his name was Gene Hackman. It became abundantly clear early in rehearsals that Hackman and Hoffman were just too close in age. Actually, Anne Bancroft, as Mrs Robinson, was one year younger than Hackman. On this question Nichols simply stated, “that’s acting”, implying perhaps there was more to the story of Hackman on The Graduate. Hoffman thought that Nichols didn’t think Hackman could do comedy, something he’d clearly later go back on. They would later work together on The Birdcage years later. Co Star Elizabeth Wilson observed that Hackman was the only person at the initial table read to not already know his lines. Ah and what did Hackman do instead? He went to star as Warren Beatty’s brother in Bonnie and Clyde, for which he was nominated for an Academy Award.

After The Graduate, it was a few years before Nichols had another success on film: 1983’s Silkwood. In an interview with Vanity Fair, actor and producer Bob Balaban said that for his “first 14 years everything he touched turned to gold. Then nothing he touched turned to gold for a while. It’s like, what happened? He could do no wrong, and for a while he could do no right”.

No one is perfect and Nichols did make some odd decisions. Leading up to the release of Postcards from the Edge (1990), he became worried how the film would do, so he rushed rather impractically into saying yes to directing both The Remains of the Day and Regarding Henry. Knowing that the former would take time and substantial work while the latter could be done fairly quickly. In fact, Postcards opened number one at the Box Office; Henry was a critical flop; and he would never get around to directing Remains, which became a Merchant Ivory classic.

Nichols made everyone feel comfortable, his actors revealed themselves in ways that they couldn’t with other directors. Neil Simon said that “he never demanded respect, he just gets it. You’re lucky to be in the same room as him”. It’s clear that he liked the finer things in life and enjoyed the world he created for himself. Mark Harris later observed that even by the time he did The Graduate, and the reason it became the film it did, Nichols “was acutely aware of how much his own life had become about buying whatever he wanted, and of how little pleasure it gave him”. Frequent collaborator Emma Thompson told Vanity Fair, “Mike was always offering me, as a guest, just the best of everything. And sometimes I’d say to him: ‘For God’s sake, let’s just have baked beans!’”

I’ve barely mentioned his hugely successful years with Elaine May and I haven’t found space to explain escaping Nazi Germany as a young Jewish boy or that his cousin was Albert Einstein! Instead, at Nichols’s AFI Life Achievement presentation in 2010, Harrison Ford described Nichols’ approach: “It wasn’t really like work. It was one of the most fun and rewarding and important experiences of my life as a person and as an actor”. Meryl Streep explained how she responded to directors that asked her what made Nichols so great: “I always get this little hollow feeling in my stomach which is a lack of anecdote because all I really really remember is being happy.”