Art & Photography, Culture, Film

François Truffaut called Jean Renoir “the greatest film-maker in the world”, a reputation based especially on the string of wonderful films he made in the second half of the 1930s, among them La Grande illusion (1937), La Bête humaine (1938) and La Règle du jeu (1939). But whereas the first two were more popular – in part because of the star Jean Gabin – it is La Règle du jeu that has, since the Second World War, regularly triumphed in film polls such as those conducted by Sight and Sound and been seen as the summit of Renoir’s status as a great auteur. While such exercises are inevitably subjective – and, as often pointed out – geared to older and often Eurocentric cinephile tastes, they are nevertheless indicative of the exceptional critical respect for the film. We might, however, ask why is it this film which is regularly singled out, given that Renoir’s oeuvre is not short of masterpieces and considering the film has no major stars as well as a sprawling, dense and complex plot.

Inspired by the theatre of Beaumarchais and Alfred de Musset, La Règle du jeu is a light-hearted drama, a ‘dramatic fantaisie’. The film is set in the Parisian upper-class milieu of the immediate pre-second world war period. The marquis Robert de La Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) invites a group of friends to stay with him and his wife Christine (Nora Grégor) in their château in Sologne for the weekend, among other things to hunt. Guests include his mistress Geneviève (Mila Parély), the couple’s friend Octave (Renoir) and a famous aviator, André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), who is in love with Christine, as is Octave. This motley crew interacts with each other and the family’s servants, especially the maid Lisette (Paulette Dubost), her husband the game-keeper Schumacher (Gaston Modot) and the poacher Marceau (Carette) in a series of comic carry-ons, until the dramatic ending in which Jurieux is accidentally killed, his death passed off by the marquis as a ‘regrettable’ incident.

*

Jean Renoir was the second son of the revered Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He initially lived in the shadow of his father, even marrying the artist’s last model, Catherine Hessling, whom he attempted, in vain, to turn into a star. First, he tried ceramics but then (wisely) abandoned art to go into film. The Renoirs in this respect are a rare example of a father-son pair in which both were equally successful, artistically and commercially, albeit in different disciplines. His famous patronym undoubtedly helped Renoir launch his career in the cinema. He first made avant-garde silent films (sometimes selling his father’s paintings to raise money) and later, more mainstream sound productions. He hit his stride in the mid-1930s when his left-wing beliefs and work aligned with the political context. While he was never a member of the Communist party, he was strongly anti-fascist and close to the left-alliance of the Popular Front, as shown in Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (1935) about a worker’s cooperative and Les Bas-Fonds (1936), an adaptation of Maxim Gorky. La Marseillaise (1938) is Renoir’s version of the French Revolution and he worked for the filmmaker’s cooperative Ciné-Liberté. La Grande illusion (1937) illustrates his pacifism and La Bête humaine (1938) the sense of disillusion that followed the short-lived hopes of the post-Popular Front era. All demonstrate the filmmaker’s fascination with social milieux, including the aristocracy in La Règle du jeu. Renoir’s wide-ranging filmic panorama of 20th century French society is unique, on a par with the ambitious 19th century literary sagas of Honoré de Balzac and Emile Zola – indeed La Bête humaine is a Zola adaptation.

In La Règle du jeu, Renoir observes the foibles, pretensions and decadence of a frivolous world dancing on the edge of a volcano, clinging to its privileges before the impending catastrophe of war. The marquis is obsessed with his mechanical toys; an old colonel repeatedly laments the disappearance of ‘class’. The ‘upstairs-downstairs’ relations between masters, guests and servants are as comic as they are revealing of class prejudice, while the celebrated hunting scene is an eloquent exposé of the class struggle, as is the cover-up of Jurieux’s accidental death – all are mercilessly dissected by the filmmaker. Yet the genius of Renoir is his ability to imbue his characters with warmth and humour, helped by a fabulous cast, enabling the spectator to connect with them whatever their faults. The most famous phrase in the film, that in this world, “everyone has their reasons”, pronounced by Renoir as Octave, encapsulates the filmmaker’s ability to view the world he depicts with critical distance while retaining compassion and empathy.

*

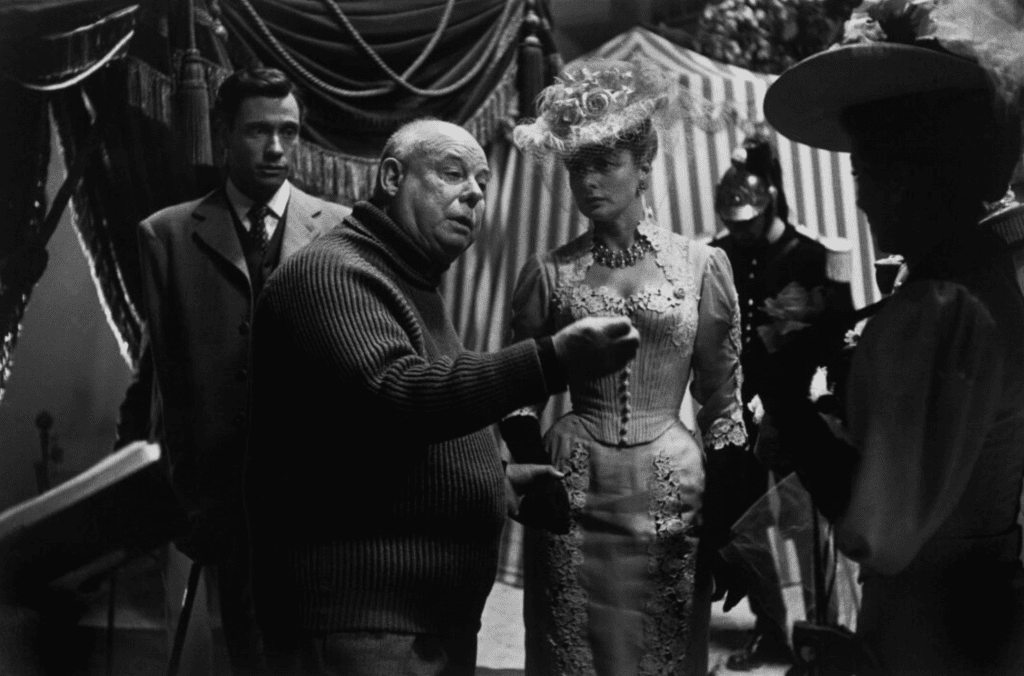

Renoir’s cinematography, particularly his long mobile takes and staging in depth, underpins his all-encompassing approach to both human and social representation. His other films include virtuoso camerawork – for example the famous quasi-360º shot towards the end of Le Crime de Monsieur Lange and the scenes among railway workers in La Bête humaine. Renoir’s visual signature, however, finds its apotheosis in La Règle du jeu, as displayed in the scenes of the arrival of the guests at the château or of their antics in its corridors at night. Long and mobile takes were quite common in 1930s French cinema. This was a style developed partly because of financial constraints and partly in response to the theatrical tradition, which Renoir was familiar with, enabling the display of ensemble acting. Renoir’s specificity was to put this visual style to the service of a politicised cinematic realism. In La Règle du jeu, he makes particularly striking use of staging in depth, deploying several layers of corridors, doorways and windows, constantly opening and shutting spaces, with characters weaving in and out of them, notably during the long, wild party that leads to the final drama.

Apart from a brilliant social commentary and the pinnacle of his visual style, La Règle du jeu is also a very personal film for Renoir. Playing Octave enables him to comment on his own social position as a bohemian artist, in the marginal space between the aristocrats and the workers, and the film makes clear his sympathy for other liminal figures such as the mischievous poacher Marceau, rather than the severe working-class game-keeper. But Octave, in a more sombre mood, also embodies the figure of the ‘failed artist’, as he demonstrates towards the end of the film, when he explains to Christine that he can never reach the level of her father, a musician who had been his mentor. While this is a fictional characterisation, it is possible to see it as a reflection on Renoir’s feelings of inadequacy as an artist unable to inflect dramatic political events or, arguably, of the difficulties in measuring up to an all-powerful father figure.

*

La Règle du jeu came out on 8 July 1939 to mixed reviews. With the declaration of war on 2nd September, its provincial and international exhibitions were cut short. Out of these circumstances, a much-repeated myth (including by Renoir) arose that the film had met with a violent cabal of hostile criticism, followed by political censorship. In actual fact, if some reviewers disliked the hybridity of the film (the ‘dramatic fantaisie’ aspect) and the acting of Nora Grégor as Christine, many reviews were positive and the film essentially suffered from bad timing. It was banned by the authorities for a few months, as were many other French films. At that point, Renoir emigrated to America and a new phase in his life and career began, but the legend of La Règle du jeu as a film maudit (cursed film) endured.

After the war, La Règle du jeu began its second, long and illustrious career. Compared to the relative simplicity of La Grande illusion and La Bête humaine, La Règle du jeu can appear difficult, yet this multi-facetted film rewards repeated viewings and yields many interpretations. Some see it as a “document of French everyday life” (Chris Faulkner), some as the epitome of the figure of the artist in Renoir’s cinema (Charles Musser); others, too numerous to list here, have looked at its theatricality, its realism, its humanism, its sardonic view of human relations, and more. A film clearly ahead of its time stylistically, La Règle du jeu perfectly conveys the specificities of French society in 1939. Yet it also rises above them, offering a profound commentary on human nature. Like all great classics, it is both of his time and timeless.