Sensual cinema—the sort that undulates, quivers, throbs with passion—is extraterrestrial.

Or, as it washes over you, lures you into thinking that you are one. Flung off to outer space, you look down to see the mundane, the everyday, cold objective reality recede into oblivion. The air pressure plummets the higher up you go. You can’t breathe. You enter an altered state, a heightened consciousness. There’s not only one permutation of this alien state, but a whole spectrum, varying in severity.

Here’s my brash attempt at organizing this spectrum by order of reality-bending escalation: Hallucinatory trip. Hypnotic episode. Reverie. Fever dream. Sorcery (the state of being spellbound). Spiritual possession. At the peak would be Nirvana—a state of utter exaltation or transcendence, yes, in the Buddhist sense—or its opposite extreme: Schizophrenia.

In any case the series of aesthetic calculations that define sensual cinema are designed to fracture objective reality in ways both subtle and violent. In its place is subjectivity or, if a work is more extreme, abstraction. It stirs up a feeling that’s idiosyncratic. You’re disoriented, you try to grapple with it rationally, intellectually, but come up short. That’s when you get it: the only way in is surrender. Sensual cinema, at its most transportive, is a purely emotional experience.

The impressionistic and elliptical back half of Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild, seen in the passages after Yuddy (Leslie Cheung) has arrived in the Philippines, can best be described as a kaleidoscope. Wong plays reality (or what tenuous hold Days has on it) not as a melange of wishes, regrets, memories, but mere wisps of them. In vain pursuit of his biological mother, Yuddy wanders the streets of Chinatown, a ghost in limbo. After Yuddy is stabbed on the train, the visions that haunt him, the kind that attends one’s final breaths, are like the fever dream on my spectrum. But the spectral hauntings are not his alone. We catch glimpses of Andy Lau (waiting by the phone booth); Leslie’s adoptive mother (receiving the infant Yuddy in her arms from his biological mother); and Maggie Cheung (waiting at a ticket booth—for Yuddy or Andy or another lover we don’t know).

The connective tissue between these images, and the animating principle behind them, is yearning. Wanting. Desiring. To possess someone that one currently doesn’t have. A state of disturbance that can only be resolved by possession. In Days of Being Wild, longing is a firefly that flits blithely from one character to the other at the most acute moments of their craving.

Still, yearning per se is not enough. An essential corollary is the impossibility for satiation, leading to an eternal cycle—a lifetime’s worth—of unfulfilled longing. One can’t exist without the other in a Wong Kar-Wai film if it is to reach its fullest power.

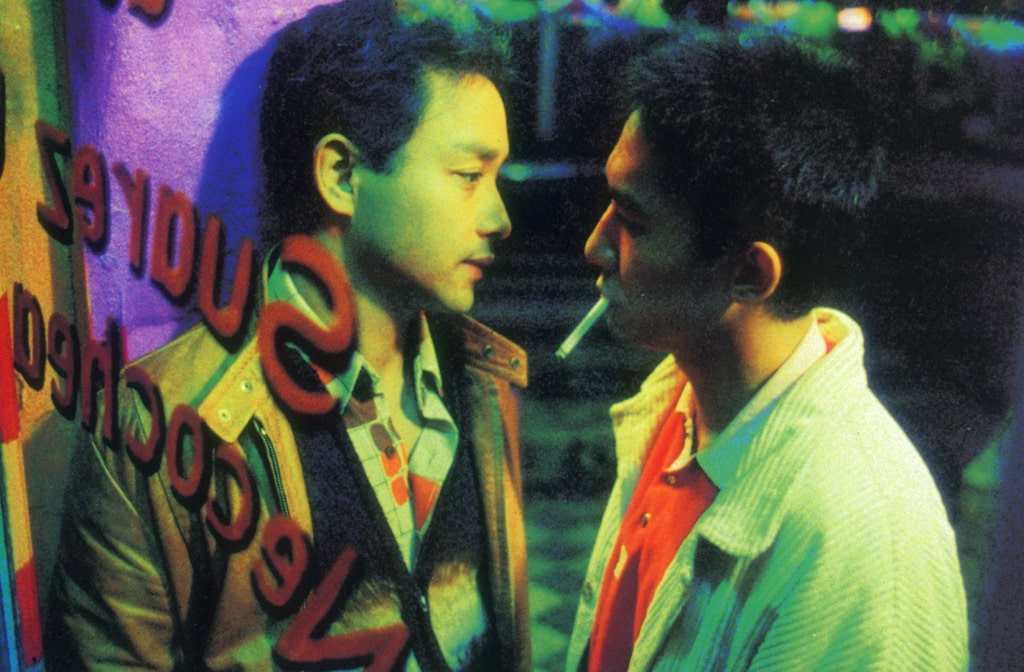

Availability, ease of access—the dearth of obstacles to possessing someone–diminishes an object of affection’s seductive power. We’re most obsessed with or tantalized by loves that are either illicit, forbidden, distant or out of reach. In Days of Being Wild, despite the playful coquetry of their first encounters with Yuddy, neither Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) or Fung-ying (Carina Lau) stood a chance. In Happy Together, Tony gets spurned by Leslie the very second he lets his guard down and lets the latter back in. The film’s greatest, impossible love in Days of Being Wild, and the primary locus of Yuddy’s profoundest affections, is his blood mother. It’s the one relationship in the film, burnished with the most nostalgia. And it is she who got away.

This is what makes Days stand apart in Wong Kar-Wai’s oeuvre: the object of its deepest longing isn’t romantic or sexual. It’s maternal, which makes it the saddest, most crushing rejection of all because—from a source where one expects love—there’s only an abyss of indifference. While Wong indulges the audience with a painfully short glimpse of the mother, Yuddy is deprived of even that. (The film shows us Yuddy in infancy and in the throes of death. His unquenched desire is reincarnated in Tony Leung’s character in the final scene, ostensibly an epilogue.) Looking in the direction of Yuddy walking away but not seeing him, the mother is poised and reserved. And yet feeling seems to roil under the surface. How much does she feel for her child? Another question that Days of Being Wild leaves tantalizingly unresolved.

Even the mother (and her unattainability) seems a stand-in for something else. Much has been lost between mother and son that can’t be regained, but what exactly? Time. Shots of clocks, interstitial title cards marked by specific dates abound in Wong’s body of work. The title of his debut (As Tears Go By) swaps time for tears; and this is no accident. But it’s not time per se that absorbs Wong, as has been endlessly chronicled by film scholars for years. On a Chungking Express commentary on the Criterion Channel, Asian cinema scholar Tony Rayns notes that Wong is “interested in time in a very [Alain] Resnais-like way, which has to do with processes of memory: what we remember from the past; what we retrieve from the past; what we reject or bury in the past.”

Oh yes, memory, naturellement. Recalling the aforementioned clash between objectivity and subjectivity, time is cold, mechanical, external while memory is anything but. It’s subjective (subject to human feeling that is) and thus slippery. It might as well be speculative fiction. Often it’s the most emotionally extreme of personal experiences—euphoric joy, romantic or otherwise, at one end; soul-crushing pain or tragedy at the other—that perpetuates the most distortion of memory. Wong’s project is thus one of imaginative reconstruction.

In his images of clocks, it’s the trajectory of the minute hand ticking toward or past a certain moment that particularly interests Wong. In less filtered early work by Days, he invites us to vicariously experience a full minute in the film’s opening. He is after what is lost in time’s passage, either slipped away or pushed away. Burrowing past its Murakami-esque whimsy, the dread of what could be lost mounts with each passing day in the first story of Chungking Express, as He Qi-wu (Takeshi Kaneshiro) obsessively collects tin cans of pineapple marked with a due date of May 1, 1994, less than a month after his girlfriend May dumps him on April 1st. Qi-wu gives himself the same deadline to win her back before moving on. In classic Wong style, he doesn’t get the girl back, and getting over her seems unlikely: the password for his pager after all is “Love you for 10,000 years.”

Quirky hopefulness gives way to devastating loss in Wong’s mature work, as the phantom of elusive happiness permeates every frame of 2046. How over the course of a life, episodes or interludes can pack in a lifetime’s worth of bliss. A transitory moment, one you’re condemned to reliving or revisiting in an infinite loop as you chase after its elusive high. 2046 is Wong’s attempt at such a remembrance, a number that acquires mythical import. It’s the number of the hotel room Chow Mo-Wan (Tony Leung) shares with Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) in In The Mood for Love as well as the number of the room he rents next to in 2046.

In the sci-fi novel that Mr. Chow writes with Wang Jing-wen (Faye Wong), itself an echo of his earlier abortive collaboration in Mood, 2046 is the futuristic utopia of his doppelganger’s dreams. And yet 2046 is undeniably about the past. Mr. Chow soliloquizes: “Everyone who goes to 2046 has the same intention, they want to recapture lost memories. Because in 2046 nothing ever changes. But, nobody knows if that is true or not because no-one has ever come back.” Mr. Chow’s dalliances and shenanigans are evidence of a man avoiding confronting his heartbreak. 2046 is about suppressed grief, an intractable pining for a bygone era. Born in Shanghai in 1958, Wong and his family moved to British-ruled Hong Kong when he was five. The Hong Kong we see in the first half of Chungking Express is not the modern megalopolis that it was in the ‘90s when the film was set but the more colorfully seedy, debauched port city teeming with immigrants Wong must have grown up in in the 60s. Days, Mood and 2046 sketch the 1960s in its various incarnations and guises; while Happy Together longs for a place only one of its characters ever reaches. Nostalgia is the defining element of Wong’s cinema and what makes it fundamentally romantic.

Resnais is an inspired reference. His work ruminates on the nature of memory, fracturing the linearity of time and disrupting narrative chronology in the process. As in 2046, his two putative lovers are stuck in time in the titular (albeit deliberately nebulous) assignment of Last Year at Marienbad. The man “X” is convinced that he and the woman “A” had an affair the year prior but in the film’s present “A” insists that she has never met him before. Whatever may have transpired between them in the past left strong (and presumably harrowing) enough of an impression to warrant persistent disavowal or equivocation on her part. In Marienbad, memory is less an act of excavation than of vandalism.

While Wong’s oeuvre appears to be expressly non-autobiographical, the epilogue from In The Mood For Love is nakedly revelatory: He remembers those vanished years as though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.

Time is the cruelest, most fickle mistress. It marches on—sadistic, unforgiving. It is lost the very moment you’re grasping it when it withers into memory. It will forever be the one that got away. Paradoxically this is what makes memory the most exquisite vessel of desire for Wong, the one constant in his magnificent obsession.

Yuddy’s loss in Days of Being Wild remains the supreme tragedy. His is a loss of what never was, unmitigated by rhapsodic or fantastical sublimation (as Wong allows Mr. Chow his imagined amour with Ms. Chan in Mood and more indulgently in 2046) or videographic memorialization (as the deaf-mute Ho Chi-mo poignantly watches his departed father being unusually upbeat on videotape). There is something to try to grab hold of, to latch on to. In Days of Being Wild there is nothing but a lost lifetime. That hollow feeling of festering is his most heartbreaking work. Like Yuddy, I have complicated feelings toward the country of my birth, the Philippines. It’s a place which cameos allusively in Wong’s films; but I’ll save my heartbreak for another time.

Want more Wong Kar-wai? Read our essay on the visual legacy of his film Fallen Angels here.