The Swedish master Ingmar Bergman was an expert at combining all five of the senses in his prolific library of films. Natasha A Fraser writes about his ideas, dreams, and imagination.

Ingmar Bergman’s strong longing was for his art to touch other humans. In my experience, the Swedish director succeeded. Never light fare, concentration is required. But Bergman’s films richly reward and resonate for weeks afterwards. It might be the kitchen scene in Wild Strawberries(1957) or Johan’s puppet performance in The Silence (1963) or Elisabet’s gleeful sneer in Persona (1966). Watching Bergman means stepping into his visuals, adapting to the sound of the Swedish language and being gripped emotionally. Whether widening your eyes with surprise or having them smart with tears, Bergman’s work pierces within. True, he made the mysterious visible, as well as exposing the soul’s battlefield. But he also turned the mirror on us: his audience.

“Faith and lack of faith, punishment, grace and rejection—all were real to me, all were imperative,” said Ingmar Bergman (1918–2007), remembered for probing the psychological depths of actors and being hailed as one of the finest filmmakers of his generation. Stanley Kubrick described Bergman’s oeuvres as “unsurpassed” in “mood and atmosphere, the subtlety of performance, the avoidance of the obvious, the truthfulness and completeness of characterisation.” Bergman viewed Persona, Cries and Whispers (1972), and Winter Light (1962) as being closest to him, while The Seventh Seal (1957) and Fanny and Alexander (1982) permanently sealed his international reputation.

There were also Summer with Monika (1953), Wild Strawberries, Through a Glass Darkly (1961), and many more. Before reeling off the Swedish director’s work or what Woody Allen termed as “a menu of amazing movie masterpieces”, realise that Bergman felt cinema-obsessed by the age of six. “If anyone had asked, I would certainly have filmed the telephone directory,” he admitted. He cared little about critical acclaim and remained uninterested in the box office results. Not that he was financially irresponsible. When required, he directed nine soap advertisements, but it was creative freedom that nourished and allowed his sixth sense. This cannot be forgotten or dismissed.

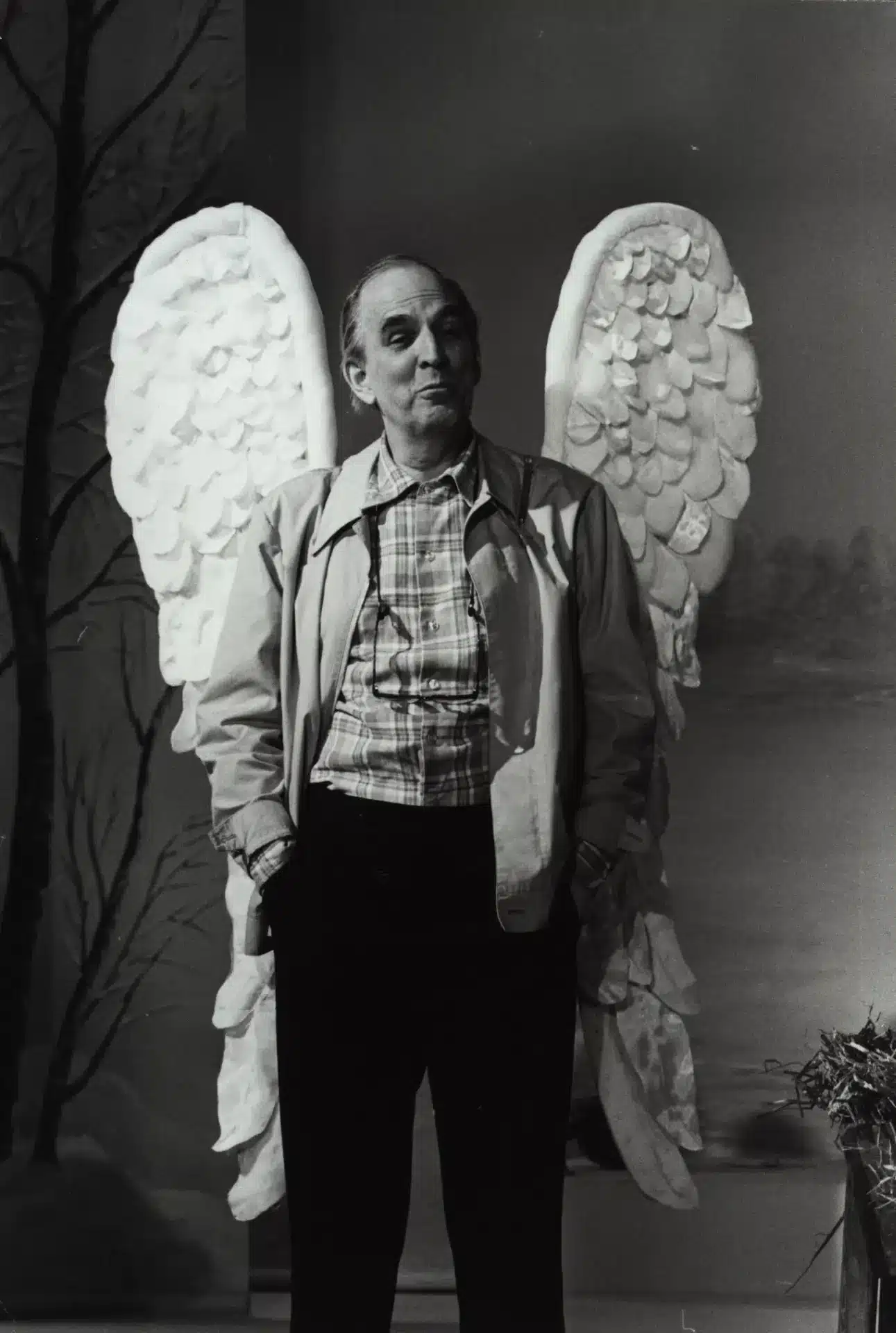

INGMAR BERGMAN ON THE SET OF FANNY AND ALEXANDER (1982). BY ARNE CARLSSON.

Despite winning four Oscars, Bergman never got Hollywood—his big blockbuster Dino de Laurentiis film, The Serpent’s Egg (1978), is woefully uneven—while Hollywood remained intrigued by Bergman, though wary. “He didn’t always make his films easy,” offers Allen. Occasionally, Bergman’s unexpected vision could strike the zeitgeist and hit a bull’s eye—as demonstrated by Cries and Whispers. To Bergman’s astonishment, the New York Times and other powerful American newspapers loved the picture. “It’s a rave, Ingmar, it’s a rave,” declared his agent Paul Kohner, even if Bergman “didn’t know what a rave was.” Nevertheless, Cries and Whispers was sold throughout the world.

In his study on Fårö, Bergman’s private island in the Baltic Sea, a wall is lined with books about him. Ranging from biographies by Peter Cowie and Geoffrey Macnab to critical commentary by Robin Wood and Laura Hubner, they are academic, earnest, and thorough. But for exalted revelation, either read The Magic Lantern, Bergman’s autobiography, or Bergman on Bergman. Or watch his televised interviews, such as his 1978 appearance on Melvyn Bragg’s South Bank Show.

A self-searingly honest showman, Bergman was his own best critic and the best raconteur about his own life. There was his childhood, reigned over by his brilliant but tortured pastor father. “What was outwardly an irreproachable picture of good family unity was inwardly misery and conflicts,” he wrote. A frequent bedwetter, Bergman was forced “to wear a red knee-length skirt.” “This was regarded as harmless and funny,” he concluded. Regarding his five marriages, nine children, and well-publicised affairs with Liv Ullmann and other actresses, Bergman must be forgiven for his Don Juan logic. “Deep down I am faithful though no one would believe it.” However, his impulsion to “exchange souls” with his partners is evidenced on the big screen. Few male directors embraced the complexity of female characters as he did.

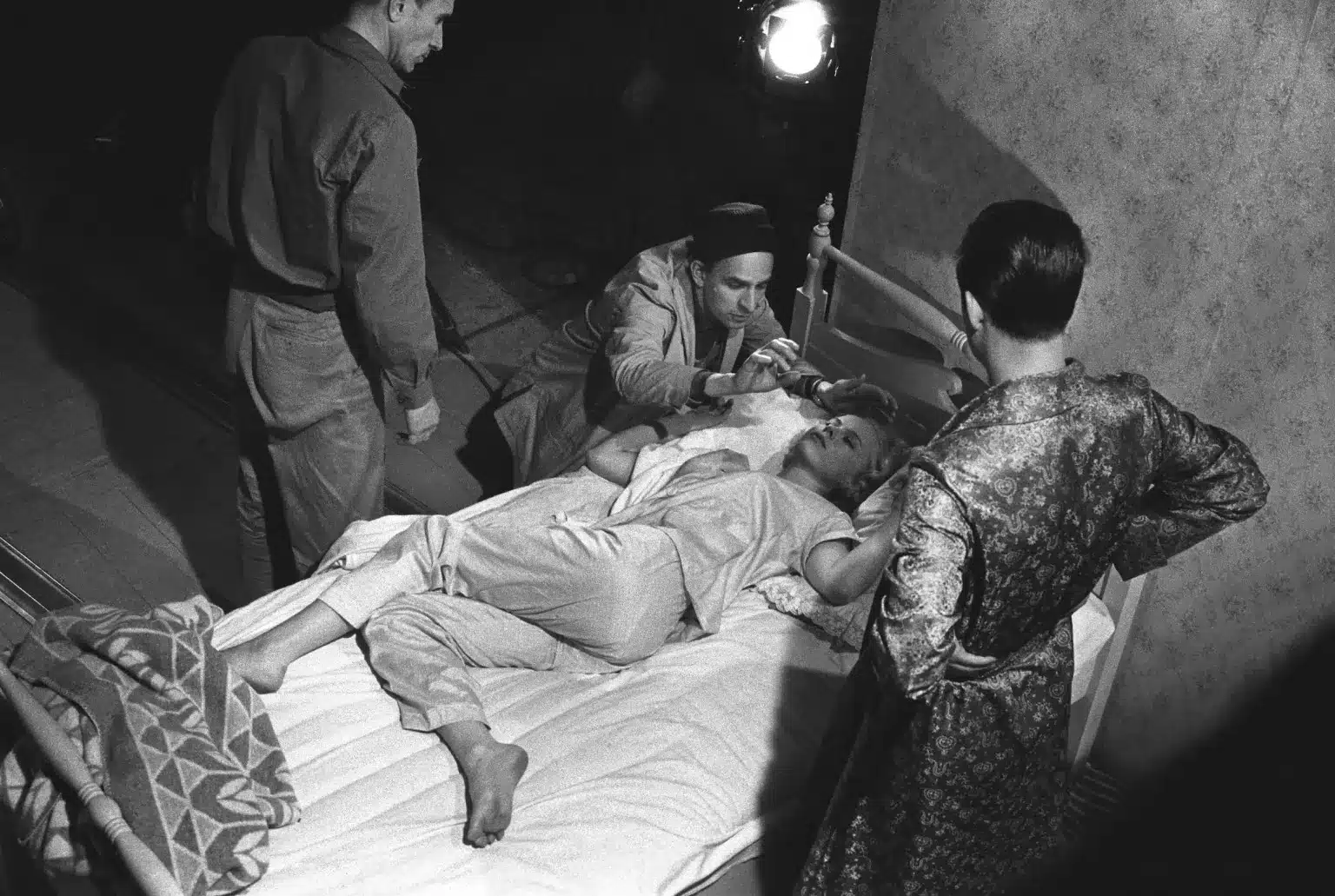

INGRID THULIN AND VICTOR SJÖSTRÖM IN WILD STRAWBERRIES (1957). BY LOUIS HUCH. COURTESY OF AB SVENSK FILMINDUSTRI.

By the age of 60, Bergman had directed 36 films as well as being in charge of five highly esteemed and productive national theatres in Helsingborg, Gothenburg, Malmö, Stockholm, and Munich. During the zenith of his career, he was directing three plays and two films per year. The actor Max von Sydow attributed this to Bergman’s stamina, strength, and sensitivity. The maestro himself cited his “irrepressible curiosity.” “I take note, observe, keep watch; everything is unreal, fantastic, frightening, or foolish,” Bergman wrote. His demons energised too, alternating between fear, rage, and grudges (“I’ve got a memory like an elephant,” he confessed) as well as demons of pedantry and punctuality. “A rehearsal is proper work, not private therapy for the producer and actor.” Fortunately, Bergman never suffered from the demon of nothingness. “And I am profoundly grateful for that,” he said.

Ingmar Bergman’s river of ideas, dreams, and imagination flowed fast and furiously. In Jane Magnusson’s Trespassing Bergman documentary (2013), Ridley Scott described him as coming from the school of everything: “A director who chose actors, wrote the script and created the mood.” Wisely, Bergman chose to control everything. Like Fellini and Warhol, his films were family-like operations. As well as the Norwegian-born Ullmann, Bergman had a stock of excellent Swedish actors that included von Sydow, Harriet Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Bibi Andersson, Gunnel Lindblom, Gunnar Björnstrand, and Erland Josephson. He also chose superb cine- matographers—beginning with Gunnar Fischer and partnering with Sven Nykvist from 1960—and, of chief importance, he was a born editor. “Film is an illusion, planned in detail,” he wrote in The Magic Lantern. “Editing occurs during filming itself.” This explains why all of Bergman’s films came in at around 90 minutes, apart from his last and final exception Fanny and Alexander. It was twice the length. Every frame counted with Bergman.

“Film is above all else concerned with rhythm,” he told Peter Cowie in 1969. “The primary factor is the image, the secondary factor is the dialogue; and the tension between these two creates the third dimension.” Bergman also believed in a certain release. “Even in the most tragic scenes, there must be some joy and lust,” he said on the South Bank Show. And there was his never-ending love affair with the face that sucked in audiences. “Bergman would put the camera on Liv Ullmann’s face or Bibi Andersson’s face and leave it there and it wouldn’t budge,” wrote his disciple Woody Allen. “Time passed and more time and an odd and wonderful thing unique to his brilliance would happen.”

Bergman was refreshing for viewing his work as open to interpretation. “It isn’t even about understanding,” he wrote. “It’s about experiencing it emotionally.” However, his admission, “I think of each film as my last,” is strange considering that most creatives feel the opposite. Put it down to the intimacy and feverish pace of Bergman’s projects. “A production stretches its tentacle roots a long way through time and dreams,” he said.

Every film buff has their list of Bergman favourites. The deeply personal list that can provoke arguments. The list that reminds of his sixth sense. Stating mine in chronological order, Sawdust and Tinsel (aka The Naked Night, 1953), Wild Strawberries, Persona, Cries and Whispers, Scenes from A Marriage (made for Swedish TV, 1973), and Fanny and Alexander—with special mentions of The Silence (1963), Hour of The Wolf (1968), and Autumn Sonata (1978), which have exceptional scenes, but lost me. “There are films that age and films that age beautifully,” reasoned Bergman. Some pictures were also close to his heart. “Summer Interlude, it’s a very, very bad picture but I like it,” he said. “Making it was extremely satisfying.” Although many genuflect in front of The Seventh Seal, I agree with director Alexander Payne that it now feels “laughable” and, as demonstrated by Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1977), easy to parody. Nor was Max von Sydow content with his performance. “I did overact due to coming from the theatre,” he told Charlie Rose.

DIRECTOR INGMAR BERGMAN AND ACTORS BIBI ANDERSSON AND JARL KULLE DURING THE FILMING OF THE DEVIL’S EYE (1960).

The Virgin Spring (1960), also starring von Sydow, followed in the same vein. “I turned to the dogmatic Christianity of the Middle Ages with its clear dividing lines between good and evil,” recalled Bergman. Perhaps it won his first Academy Award, but Bergman dismissed it as “touristic” and “a lousy imitation of Kurosawa.” Sawdust and Tinsel, on the other hand, remains an ignored masterpiece and up there with Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932). Described by Bergman as “a very brutal, very clumsy fairy tale”, the film captures his lifelong enchantment with the big top—when he was little, he actually lied that his parents had sold him to Schumann’s circus. It is hard to forget the jeering crowd and doomed chivalry of clown Frost (Anders Ek) who strips off, jumps in the sea and falls Christ-like, carrying his wife. Nor the compassion that the Goya-like Anne (Harriet Andersson) incites as the brittle mistress and brave little trooper, riding around in Andalusian black lace headgear.

“His admission, ‘I think of each film as my last,’ is strange considering that most creatives feel the dire opposite. Put it down to the intimacy and feverish pace of Bergman’s projects. ‘A production stretches its tentacle roots a long way through time and dreams.’”

Wild Strawberries was inspired by Bergman’s stays with his maternal grandmother. A positive childhood influence, she treated him “with harsh tenderness and intuitive understanding.” (Before going to sleep, he often imagined walking through each of her rooms.) Victor Sjöström plays Professor Isak Borg, who flits between the past and present reflecting on the loneliness and disappointments in his life, set against the former family villa and bucolic northern Swedish countryside. Although Bergman nursed his doubts about Wild Strawberries, Sjöström’s melan- cholic dream state mesmerises, evoking Fellini’s 81⁄2 (1963)—albeit the Nordic version.

“Two women meet, compare hands and they start merging into each other” was Bergman’s description of Persona (1966). Accompanied by Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann, he was promoting his mysterious masterpiece on Swedish television. “Each person should experience it the way they feel,” Bergman advised. “And that’s very important for me, the idea that you can never understand a film like this.” His most iconic film, Persona seemingly concerns a famous actress, Elisabet Vogler (Ullmann) who dries up on stage and becomes speechless. Alone on a private island with a talkative nurse, Sister Alma (Andersson), she listens, absorbs, and pens her condescending observations in a letter to the nurse’s boss. Much is made of the emotional vampirism between the two women, particularly due to Sven Nykvist’s memorably sensual black and white cinematography. But it’s also the powerplay of silent beauty versus someone keen to communicate. Though the circumstances are extreme in Persona, the scenario typifies women. Intimacy is fractured by that burning need to feel superior. Taking it further, in Autumn Sonata, Bergman exposes a famous mother who needlessly eclipses her frumpy daughter.

INGMAR BERGMAN. BY BENGT WANSELIUS.

Cries and Whispers was inspired by Bergman’s “vision of a large red room with three women in white whispering together.” Once again, it is a study of females and concerns the dying Agnes (Andersson) and her more beautiful, privileged sisters Maria (Ullmann) and Karin (Thulin). Though they claim to be loyal and concerned, it becomes obvious that only Anna (Kari Sylwan), Agnes’s devoted maid, genuinely cares. “It’s the same old film every time,” Bergman told Andersson afterwards. “The same actors. The same scenes. The same problems. The only thing is we’re older.”

Scenes From A Marriage was a Swedish television mini-series. Over the course of six hour long films, it chronicles the disintegration of the marriage between Marianne, a divorce lawyer (Ullmann) and Johan, her husband (Erland Josephson), a psychology expert. Inspired by Bergman’s 12-year relationship with Ullmann, it is utterly absorbing and feels utterly contemporary. To re-quote Bergman, it becomes “the same scenes, the same problems” when a man leaves his wife for a much younger woman. Tying the Ingmar Bergman bow, Fanny and Alexander was a well-deserved triumph—both critically and commercially. Exquisitely filmed by Sven Nykvist, it boasts the enchanting scenes around the family table, the vile pastor played by Jan Malmsjö, beautifully dressed children, and manages to finish with August Strindberg, Bergman’s favourite Swedish playwright. Though a sumptuous and charming visual feast charged by flawless performances, Fanny and Alexander lacks Bergman’s precision.

The Oscar-winning motion picture would be his last. “Making films is for young people,” he said. Not that he stopped loving motion pictures. “It is my drug to go to the cinema,” he admitted. Indeed, every afternoon in Fårö, at 3pm sharp, he watched mostly silent films in a converted 17th-century barn-turned-cinema. “You don’t hear what they say but you feel what they say,” Bergman said. “That is pure magic.” It is hard not to imagine the distinguished director—domed forehead, strong nose, hair swept behind prominent ears, long legs casually crossed—sitting alone within the quiet of the dark.