Perhaps you can’t identify him like a Spielberg, Scorsese or Coppola but there’s no doubt Sidney Lumet has influenced your film viewing life as much as anyone. A prolific filmmaker, Lumet is responsible for some of the most iconic American films of the 20th century. June 2024 would have marked his 100th Birthday—he died back in 2011—and learning that provoked me into thinking about his filmography in some detail. Hopefully this educates those that don’t know his films and those that do know can settle in and enjoy a trip down memory lane.

Lumet began his career as a child actor, having some notable success in various productions on Broadway. His parents were Jewish theatre veterans who settled in New York from Poland some years before Sidney was born. Broadway acclaim was somewhat interrupted by World War II, the young Lumet put everything on hold when he joined the US Army as soon as he could in 1942, at 18. Upon his return he became part of the original Actor’s Studio group where his contemporaries included Elia Kazan and Montgomery Clift. Though obviously an influence on the young director, the school frustrated Lumet who found their obsession with “realism” frustrating. Curious to explore other techniques he set up his own theatre group starting to direct television assisting Hollywood legend Yul Brynner.

Lumet quickly developed a reputation for being a quick shooter full of enthusiasm, enterprise and economy. Before long, that reputation led him to direct an adaptation of Reginald Rose’s play, 12 Angry Men, which was released in 1957. Actor Henry Fonda had seen the original broadcast of Rose’s play on CBS. So taken by it, he bought the rights.. Lumet, with a strong reputation in theatre but most importantly television, was the man Fonda picked to take on the boilerplate drama. I’m reminded of the story behind Mike Nichols getting hired to direct Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), another theatrical adaptation film debut. Nichols was chosen not so much because of his Broadway success, which pleased the studio, but because Elizabeth Taylor felt that she would be able to control him, that he wouldn’t tell her to do anything she didn’t want to do. Perhaps there was a bit of this in Fonda and Arthur Krim, the head of the studio, but Lumet remembered their decision more favourably. He later said, “Arthur was never afraid to give directors their first movie. I don’t know how many directors he gave their first movie to. He was wonderfully courageous in that way. He didn’t hesitate for a minute when Hank and Reggie [the author] chose me”.

The film all takes place in one room, we watch as a jury deliberates over a teenager charged with murder. The drama and intrigue comes from the disagreement and conflict of the jurors as they question their morals and values. In the hands of a lesser filmmaker this could have been an unbearably slow and meaningless 90 minutes. We see from this very first film how Lumet was a master at blending bold and clear storytelling with first-rate performances. We also see his willingness to let the written word drive the story.

Most will remember 12 Angry Men (1957) for Fonda’s powerhouse performance at the centre of it all. Fonda was already established—a wonderful actor and an iconic star that could have walked all over Lumet but instead this began Lumet’s run of directing career-defining performances. Over the next seven years, there were further collaborations with Fonda as well as films with the likes of Sophia Loren, Marlon Brando, Robert Redford, Katherine Hepburn, Ralph Richardson, Rod Steiger and Walter Matthau. No wonder he had that reputation for moving quickly and getting things done. The speed would lead to a few missteps but we mustn’t dwell on those too long.

At the end of this prolific 8 years would come a film starring none other than Mr Bond himself, Sean Connery, having just finished his third Bond film and about to start his fourth. In 1965, The Hill would mark the first of five collaborations between the actor and the director. The more successful of those are the ones that lean into the Connery aura, best to stay away from Family Business (1989) in which we are to believe Connery, Dustin Hoffman and Matthew Broderick as three generations of the same family. No. Back to The Hill, which also holds a rather niche bit of relevance in Connery’s filmography in that it is the first time he goes without his famous hairpiece. Could it be that Lumet found a way to swerve away from vanity and towards authenticity?

The Hill follows a group of British soldiers in a detention camp in the Libyan Desert. Connery plays Sergeant Major Roberts whose conviction for the assault of an officer is a mystery. As punishment, the sadistic Staff Sergeant Williams orders the prisoners to climb a man-made hill again and again in the desert heat. The film is really about British colonial impotence in the 1960s. We see Lumet again excel with first-rate performances, brilliant writing and epic themes through an intimate lens.

There is something intriguing about Lumet’s interest in British society. On an intellectual level, he is curious about a world far away from his own. Just as he was at the Actor’s Studio and perhaps to when he turned 18 and joined the army. Other examples of the British interest come in the form of a John Le Carré adaptation, The Deadly Affair (1967), the Academy Award-winning version of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and Equus (1977), starring Richard Burton.

In The Hill (1965), Lumet strips away Connery’s Bond persona and instead we get the full force of his rugged masculinity, perhaps in no small part thanks to the physically gruelling shoot. The Hill is a really surprising film that shares DNA with the likes of The Great Escape (1963) and Bridge Over the River Kwai (1957) but has a toughness that eludes those other films.

As we move through the late 1960s and early 70s, Lumet continued his prolific output. In 1973 he introduced us to Frank Serpico, an honest cop trying to make the world a better place. With a refreshing and surprising structure that sees us move through a life in a kind of voyeuristic way Serpico is the story of a man, played by Al Pacino fresh from the first Godfather film in 1972, continuously trying to improve his department while constantly being let down and knocked back by circumstances and the people around him. Serpico sits comfortably alongside Chinatown (1974), The Godfather (1972), The Conversation (1974), Taxi Driver (1976) and American Graffiti (1973) in the next evolutionary step of the New Hollywood that was emerging in the 1970s.

Not exactly physical in the same way as The Hill, Serpico was nonetheless a tough shoot. The film features 107 speaking parts in 104 different locations set over 11 years. All this adds to the scale of the film, we see the epic journey of this man’s life in so much detail. Again we return to the relationship between the epic and the intimate. Again we see how good guys can be bad and how bad guys don’t have to be so bad. In an interview on the release of the film, Lumet explained how he wanted Serpico’s colleagues to be “men with charm, who were all the more evil for being human and understandable”. William Friedkin, the iconic director of The Exorcist (1973), described this period as being about showing “you the good inside the evil person and the evil inside the good person”.

Though Pacino perhaps remains best known for the work he did in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather trilogy, it is with Lumet that he arguably did his best work: In Serpico but also a couple years later in Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Should you have not seen either film then you now have something to do tonight!

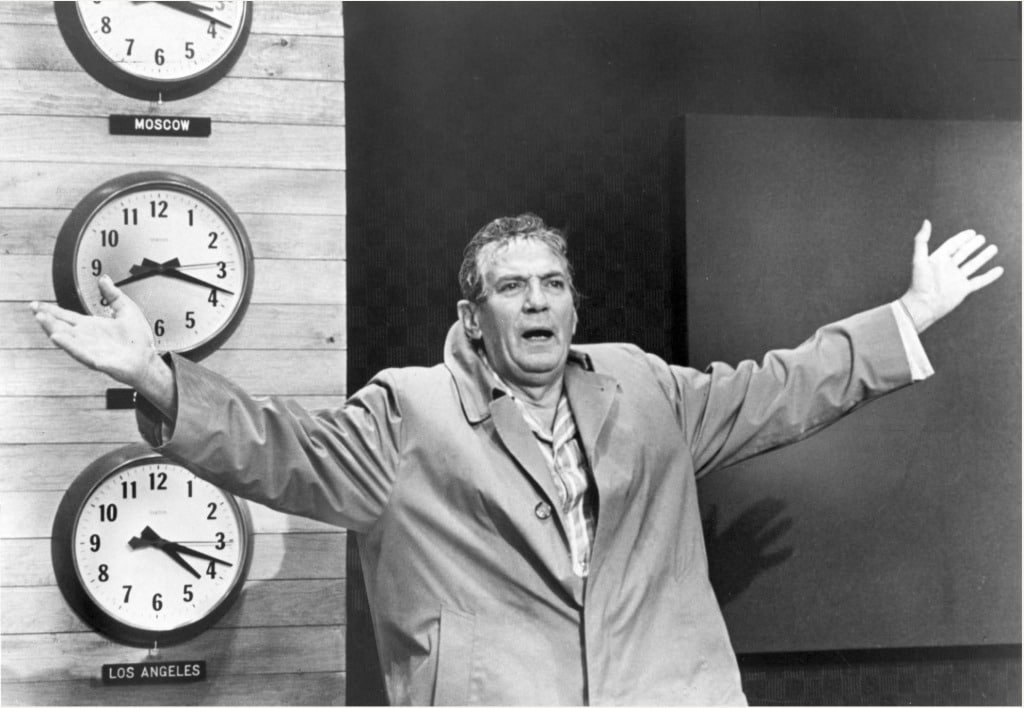

The year after Dog Day Afternoon, Lumet released the most important film for this piece. Not because it is among my favourite films, which it is, but because it also featured the final film performance from the exceptional Peter Finch, whose son, Charles, is A Rabbit Foot’s Editor in Chief. In Network (1976), Finch is magnificent as Howard Beale, a man at the end of his tether whose on-screen outburst leads to mass hysteria, corporate fury and personal sacrifice. Network is the great satire of the television industry, specifically the News, and charts the next stage of American societal decay that he began in 12 Angry Men and concluded with in Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead (2007). There are some who think satire is misleading when it comes to Network due to the fact that everything it predicted has come to pass. Among its many fans is Aaron Sorkin who once wrote, “no predictor of the future, not even Orwell, has ever been as right as Chayefsky was when he wrote Network.”

With the possible exception of Peter Finch in Network, there is one performance in a Lumet film that rises above all others. An over the hill movie star giving perhaps the best performance of their career, fertile ground for Lumet. The Verdict (1982) starred Paul Newman as a boozy ambulance chaser happy to sell out his clients until he is struck by an opportunity and injustice playing out in front of him. With the words of David Mamet, Newman gives such a moving performance as Frank Galvin. He is not a likeable man, he is not particularly kind nor particularly clever, and yet we root for him at every turn.

The film is a cerebral restrained look at the legal world. Newman’s outcast alcoholic trying to salvage his career and self respect on a medical malpractice case is rather reflected in Apple TV+’s 2024 series Presumed Innocent, which takes clear visual and tonal inspiration from this classic. The same could be said of Tom McCarthy’s Academy Award winning Spotlight (2015), which also deals with the church in Boston and a certain amount of malpractice.

The rest of the 1980s, the 1990s and the early 2000s saw a collection of decent (Running on Empty, Q & A), passable (Power, Night Falls on Manhattan, Find Me Guilty) and dreadful (Gloria) films from Lumet. Then in 2007 we are gifted with Lumet’s final film, Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead. Like a bolt from the blue, this is perhaps the best last film by an American Director.

It deals with the most base, darkest desires of the human mind. Two brothers conspire to rob their own family jewellery store. Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke star in the lead roles, in this powerful film with its Shakespearean themes (King Lear features throughout) and modern American setting, Albert Finney and Rosemary Harris play their parents with few words and little to do but both convey so much with so little.

Like 12 Angry Men, this film deals with moralising and philosophy around a terrible crime, though this time we the audience are the jury. As in The Hill we see men pushed to their limits, tested by the society in which they’re living to the point of desperation. Serpico would have made light work of these brothers though they wouldn’t have been out of place in his corrupt world. Finally, like The Verdict, Lumet’s final film uses the law to tell the story of the human condition.

We could also link all these films as chapters in the degradation of Post War America. Even in 2008, Lumet had concerns for the way the world was going. He told Sight and Sound, “I am not optimistic at all. I think we’re at a terrible point in our history and I hope we can turn it around”.

This leads me to wonder once more what Lumet would have made of the film world today. In that same interview, Lumet bemoaned the impact of modern media on society, “The experience of watching TV is isolating and that isolation keeps growing. There’s even the idea that my film will appear on a cell phone—and that’s isolation reduced to an image of two by three inches. It’s a horrible idea and that increasing isolation is showing up in all aspects of our lives”.

Hopefully these Sidney Lumet highlights I’ve picked out gives some sense of the kind of filmmaker he was, one of the true greats, both prolific and specific. He did also, and I can’t recommend this highly enough, write the definitive book on filmmaking, called Making Movies (1995). It is from that book I conclude, in Lumet’s words, “I don’t know how to choose work that illuminates what my life is about. I don’t know what my life is about and don’t examine it. My life will define itself as I live it. The movies will define themselves as I make them. As long as the theme is something I care about at the moment, it’s enough for me to start work. Maybe work itself is what my life is about.”