Babygirl opens with an orgasm, but it is by no means the film’s climax. Kitty Grady speaks to the film’s writer and director, Halina Reijn, about working with Nicole Kidman, breaking America, and the beast inside of us all.

“I grew up in communes and cults. I was named by a guru,” Romy, the protagonist of Babygirl (2024), tells her assistant a short way into the film. A mother, wife, and CEO of an automated warehouse company, Romy’s early revelation already comes as a surprise. Played by Nicole Kidman, the Stepford Wife-coded character is uncomfortable with letting her hair down. After a sex scene in which she straddles her husband Jacob (Antonio Banderas) and comes to a pitch-perfect climax, she runs to her laptop to load porn, lying face down on the floor as she finishes herself off in the dark. “I thought you were raised by robots,” her assistant responds. Romy hasn’t orgasmed with her husband in 19 years, we later learn.

It only takes a quick Google search to discover that being raised in communes is a biographic detail Romy shares with the film’s director and writer Halina Reijn, who I speak to in a pinky-red jewel-box room of the Soho Hotel in London. Reijn, 49, is wearing a short velvet dress with a Peter Pan collar and long black leather boots (styled herself, she admits proudly). Romy is indeed an alter-ego, and she describes the paradox of her upbringing by radical hippies in a Pippi Longstocking village in the Netherlands. “I was a product of the sexual revolution, my parents were super involved in all that, but I find it interesting in my life that sexuality is something I suppressed instead of feeling at ease with,” she explains, in her assonant Dutch accent. “And I think that goes for a lot of women, where we are not at ease with the beast inside of us. Romy has to learn to accept that part of herself. Because when you suppress it, you will start to do things that are risky, like having affairs.”

In Babygirl, that is exactly what happens. On her way into the office, Romy catches sight of a young man taming a feral dog with a cookie. Samuel, played with Balenciaga-seriousness by Harris Dickinson, turns out to be a new intern at her company. Not much over the age of 19, he stands out for his height as much as his cocksureness. The assistant apologises to the CEO for the new recruit’s insolence. “Do you always have cookies on you?” Romy asks.

At his request, Romy is selected to be Samuel’s mentor (in a scheme she is signed up to unbeknownst to her). Already fighting with an early flush of lust, Romy reluctantly agrees to a short meeting in a soundproof basement office, a kind of interrogation room from where their wild liaison is unleashed. Romy meets Samuel in a cheap hotel room. “A womb meets an Amsterdam brothel,” says Reijn of the production design, which oscillates between the pellucid geometry of their office and more abstract spaces where desire can flourish. “It’s a fairy tale,” says Reijn. Quickly, Romy is on all fours—a willing if flinching subject for Samuel’s sexual dominance. She comes to (real) climax with a discomfort that is also a release. “I think I need to pee,” says Romy, in what may be one of the year’s most erotic film lines.

The film is explicit in exploring a desire for abandon (Romy’s pleasure is invariably experienced horizontally, floor-bound, in contrast to her upstanding professionality); a powerlessness that can offer its own kind of liberation. While the film does include more clichéd hallmarks of eroticism—a montage shows Romy and Samuel snatching moments in elevators and bathrooms—Babygirl is notable for the absence of penetrative sex, opting instead for sex scenes more temporally and technically accurate of the time it takes woman to climax. Reijn was inspired by the so-called “orgasm gap”—the fact that women are far less likely to climax than men—a dynamic perpetuated by mainstream cinema. “Maybe 1% of women can [in real life], but in 99% of Hollywood movies, women orgasm because of penetrative sex,” explains Reijn, who cites 1980s erotica such as Dangerous Liaisons (1988), Fatal Attraction (1987), and 9½ Weeks (1986) as influences. While the film was initially intended as a summer movie, the SAG strikes led to delays. With its affectless Christmas backdrop and Kidman casting, the chief reference of Babygirl is Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut (2001), which Reijn was also interested in reinterpreting. “I’m very jealous, I’m a Scorpio—so I really relate to Tom Cruise when Nicole tells him about her fantasy and he can’t digest it,” says Reijn. “I don’t think it’s a sexist film, but we don’t go on a journey with Nicole. My movie is what would happen if she actually had the affair.”

This is not Reijn’s first rodeo when it comes to depicting deeper, darker undercurrents of female desire. Her first cinematic experience was watching Annie (1988) at the age of six. The singing and dancing American orphan proved to be a corrupting force. “We weren’t allowed to watch TV or any moving images because my parents thought that was bad for the development of the soul. We had a babysitter who was bored because we only had wooden toys to play with. She took us to the cinema without my parents’ permission,” says Reijn. “And my parents were right. It changed me in my core, in my DNA. I wanted to become a miracle child. I wanted to be famous like Annie.”

During her formation at Maastricht Academy of Dramatic Arts, Reijn was offered a part as Ophelia in Hamlet—Shakespeare’s suicidal heroine gets a namecheck in Babygirl, as the spurned love interest of Romy’s daughter. Reijn went on to become one of the Netherland’s most ubiquitous acting talents, starring in Dutch classics such as De Passievrucht (2003) and Paul Verhoeven’s Black Book (2006), as well as stage adaptations of Chekhov and Ibsen. She cites her title role in the latter’s Hedda Gabler as her favourite ever performance (taken up in 2006 and 2012), about a woman who is trapped in a marriage and kills herself. In 2015, she played a teacher who falls in love with an underage student in De Leerling. Yet there was something missing for Reijn in acting alone. “I also thought that Annie made the film herself—wrote it and directed it, which turned out not to be the truth,” she says. “But I always wanted to do that, really.” In 2019, she made her directorial debut with Instinct, about a prison psychologist who falls for a former rapist in her care, and in 2021 she directed television series Red Light, a drama about Amsterdam’s sex workers. “It took me eight years to make because nobody believed in my ideas. I had to fight so hard against Dutch normality and cookie-cutter ideas of women.”

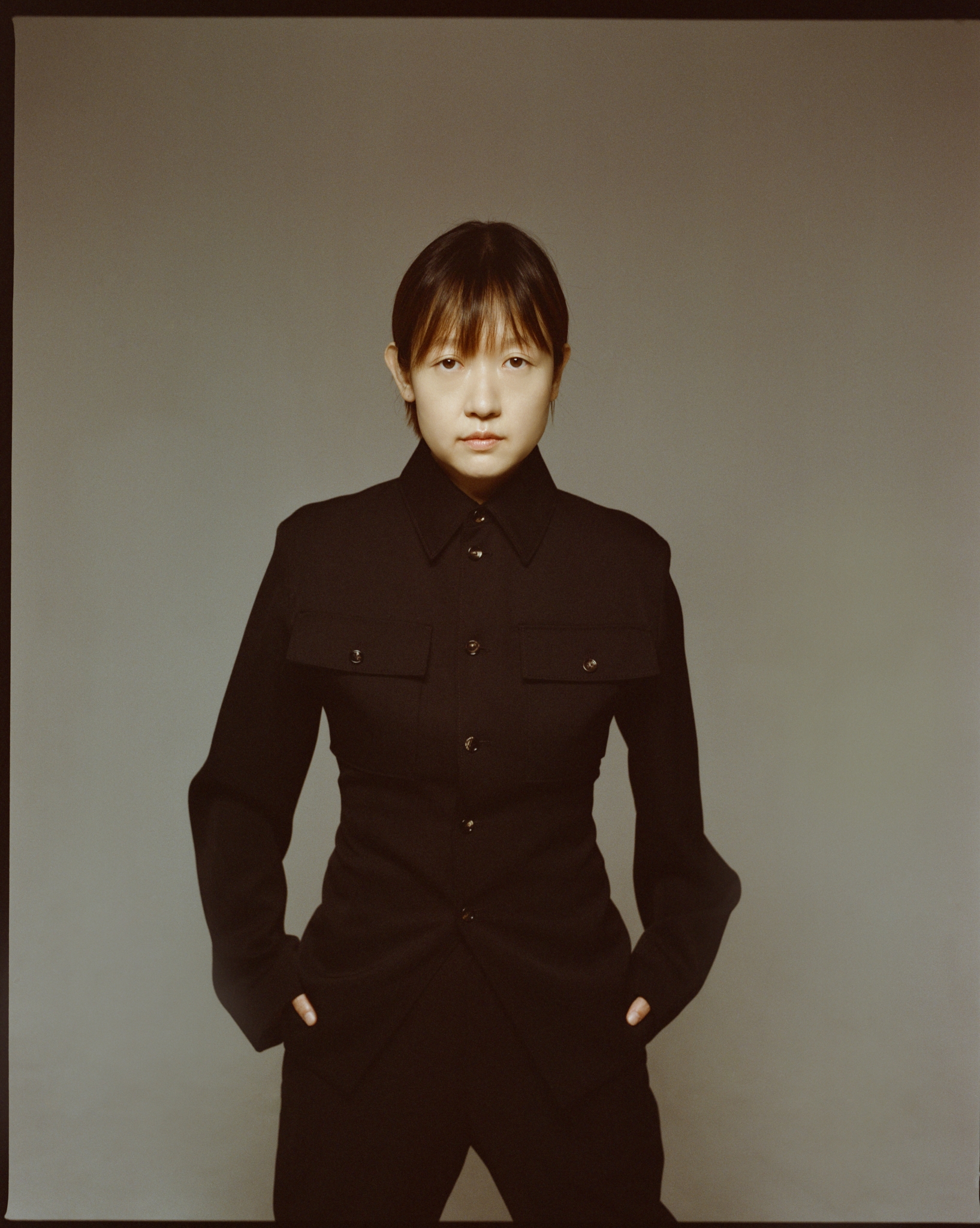

Halina Reijn by Fatima Khan

Across the pond, things were different. Her work caught the attention of production company A24, who brought her in to direct Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022), a Gen-Z murder mystery lit with iPhones starring Pete Davidson, Maria Bakalova, and Rachel Sennott (whose character has also played Hedda Gabler). Making the film marked a shift for Reijn. “It took me out of my comfort zone. I discovered humour and I discovered America,” she says . “I was inspired by the actors, who taught me so much about how they view sexuality and their bodies. That was hopeful to me. It was so different to how I grew up and how I was taught as an actress to behave.” For Reijn, America is a paradoxical space, whose “suppressed sexual culture” she identifies with, but, unlike in her home country, has offered Reijn a platform to express her ideas about this suppression freely. “In America nobody tells me I’m an alien,” she says. “In the Netherlands I often feel like I’m not normal. I don’t have children and I don’t have a partner. In New York my neighbour is 85 and is an old poet who has never married. In New York there are so many women that have beautiful lives on their own with a girlfriend or seven cats. My sisters, they’re both married and have children. They look at me like, are you insane?”

In approaching filmmaking, Reijn heeds the advice she learned from former collaborator and fellow Americanophile Paul Verhoeven to always have a question in mind. With Bodies Bodies Bodies she was asking why she was so obsessed with her phone. With Babygirl the question at hand is more philosophical: “Can I accept all the parts of myself?” (When asked if she has a phone addiction, Romy responds ‘No, I just have a job’). “Conflicting layers in a personality interest me,” Reijn explains. “I think humans are schizophrenic in what they want and need and feel. We so often see a male CEO who wants to be dominated, but women haven’t got space to tell any stories, basically.”

In the Netherlands. “I was a product of the sexual revolution, my parents were super involved in all that, but I find it interesting in my life that sexuality is something I suppressed instead of feeling at ease with […] And I think that goes for a lot of women, where we are not at ease with the beast inside of us. Romy has to learn to accept that part of herself. Because when you suppress it, you will start to do things that are risky, like having affairs.”

Halina Reijn

During her career as an actor, when anxious about going on stage, Reijn would often think about Kidman, channeling her “fierceness and willingness to tell stories that are daring.” Then, one day Kidman got in touch with Reijn. She had seen the film Instinct, and appreciated its depiction of female sexuality. “Not a lot of people outside of Europe had seen it, so her finding that tiny Dutch movie was very meaningful,” says Reijn. “We started to talk about creativity and who we were as actresses. We connected over a lot of things. When I said I was making a movie called Babygirl she was immediately very interested, even just at the title.” When I comment that this is Kidman’s second ‘cougar’ film of the year, the first being A Family Affair (2024), Reijn quickly corrects my use of that term. “Yeah, because for men, for hundreds of years, that’s all we’ve seen. Jack Nicholson is paired with someone his own age, you think ‘Why is he with that older woman?’”

Kidman and Reijn’s collaboration is its own story of love and self-discovery, the pair touchy-feely in press videos and media appearances. Reijn describes filming the nightclub scene, when a buttoned-up Romy arrives at a rave and kisses a random girl under strobe lighting en route to her lover as among her favourite scenes to shoot. “[Nicole] hadn’t been at a rave in a hundred years,” says Reijn. “Even between takes she kept on dancing.” Harris Dickinson played harder to get. Reijn had seen him in Ruben Ostlund’s Triangle of Sadness (2022) and Beach Rats (2017). “I thought, that’s him. It took a bit of time. He demanded a second conversation. I was like, oh my God, he needs to say yes.” Even over a Zoom call, the chemistry between him and Kidman was tangible. “They’re both very strong headed. But also very vulnerable. They can both switch from being super confident to these little children. That is exactly what the movie is about, having an inner child who is scared. But we also have a dominator in us.”

As a tale of Boomer meets Gen-Z, Babygirl’s thematic terrain is effective as well as financial. Romy is the you-can-have-it-all girl boss, with two houses, two children, and a military-style beauty regime. We never see where Samuel lives, but we do see him at his second job (as a bartender), where at one point Romy comes simpering for forgiveness—he ignores her, icily. On two occasions, Samuel appears in Romy’s house. “I’m a cuckoo in the nest,” he jokes, his bestiality swapped for something more fragile. In a citable scene from the film, Samuel orders Romy a glass of milk and watches her drink it across the bar. “I drew from my own experiences with younger men where they are attracted to strong, sometimes older women, but at the same time they can be very boyish,” notes Reijn. Having, in the previous scene, made her lick milk off a plate like a cat, in bed Samuel asks Romy to hold him.

Does Samuel even exist? “He asked for consent during S&M scenes. He’s both strong and vulnerable. He takes all the time in the world to make her climax,” says Reijn. “He’s a little bit of a fantasy, right? I just say my movie is a comedy of manners, it’s a fable, and we make something very extreme to start a conversation. We’re purposefully flipping everything on its head. We’re literally mirroring Kim Basinger dancing for Mickey Rourke in 9½ Weeks. We have Harris dancing for Nicole,” Reijn admits. “I also hope that women will dare to think a bit more about what they want. Instead of thinking, how do I please my partner? Think: what do you want as a woman?” Reijn herself, however, has a long way to go. “I would hope to have another relationship at some point, because I’ve been alone for quite a while. I live like a nun. I don’t date. I don’t understand the apps. And I wish to break out of that. I hope my movie will help me to have a little more fun.”

Romy’s cuckolded husband Jacob is a playwright, who, during the course of the film is working on his own production of Hedda Gabler. Ironically, he is the only character in the film ignorant to the narrative developments that are happening in his wife’s life. Yet he provides what might be the film’s most profound insight. “It’s not about desire, it’s about suicide,” he says, wrestling with his actors’ interpretation of their roles. “With any real crisis in your life, you want to start over, be reborn,” says Reijn. Romy similarly sees death on the horizon. “She keeps on saying that the avalanche is coming. She uses Samuel as a weapon to cut herself and start again.” The film’s ending—spoiler—sees Romy reunited with her husband, having sex again, better this time. Yet, with her head under a pillow, Romy’s mind still might be elsewhere, with Samuel. “I don’t see it as a Walt Disney ending,” says Reijn. “Real intimacy can allow you to be in your own world while there’s ghosts sitting on our beds—our exes, our fantasies… a scene that aroused you.”

Foot Note

On her favourite erotic film scene, Reijn cites Stephen Frears‘ 1988 Dangerous Liaisons. “It’s a scene with John Malkovich and Michelle Pfeiffer—at that moment Michelle Pfeiffer [Madame de Tourvel] is incredibly in love with John Malkovich [Vicomte de Valmont], which she’s not supposed to be,” says Reijn. Valmont seduces her, but right before they kiss, he backtracks. “He just leaves her there, hungry,” adds Reijn. “It’s just the most erotic, sexy thing I’ve ever seen in my life.”