Art & Photography, Culture, Film

We’re all very used to actors telling us who to vote for and what to care about but few contemporary figures straddle the worlds of Cinema and Politics like Glenda Jackson, the only British Oscar winner to have swapped the bright lights of Hollywood for the shabby corridors of Westminster as a Member of Parliament. Glenda Jackson has always been a trailblazer, at one point perhaps the most vital actress of her generation. She may not be thought of in the same way as her contemporaries however having retired from acting in the early 90s. Maggie Smith, Judi Dench, Eileen Atkins and Rosemary Harris all immediately come to mind thanks to their more recent film and television work. How fun to imagine the roles that we might have seen Jackson in had she not retired when she did. Perhaps Aunt May, in the Tobey Maguire Spider Man films instead of Rosemary Harris. Or scolding Oscar Isaac as Eleanor of Aquitaine in Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood. And there must have been a role for her in Harry Potter, but most obvious is that Jackson, and not Judi Dench, could have reprised her role as Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love.

First performing with an amateur dramatic society after school, it was years later as Elizabeth I that Glenda Jackson is perhaps best known in both the hugely acclaimed television series, Elizabeth R, and opposite Vanessa Redgrave in Mary, Queen of Scots (both 1971). She even won two Primetime Emmys for the former. Amateur dramatics led Jackson to writing to drama schools and getting a place at RADA, paid for by Cheshire county council after being requested by her manager while working at Boots. Upon graduation, Jackson found herself in a new kind of theatre that was emerging in the 1960s. She cites John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger and the new dramatists of the era that changed the kind of theatre being created. The class structure of what theatre, and film, wanted to look at was changing and Jackson embodied that with her Cheshire accent and modern attitude. She joined the RSC in 1963, which proved to be a great success —in particular in Marat/Sade for Peter Brook in 1964. In the late 1960s, long before The Lair of the White Worm or Celebrity Big Brother, Ken Russell was known for his brilliant imaginative TV films about artists and musicians. In 1967, he released his first major feature film, Billion Dollar Brain, before moving on to a stunning adaptation of DH Lawrence’s Women in Love. This would be the first of six collaborations between Russell and his leading lady, Glenda Jackson.

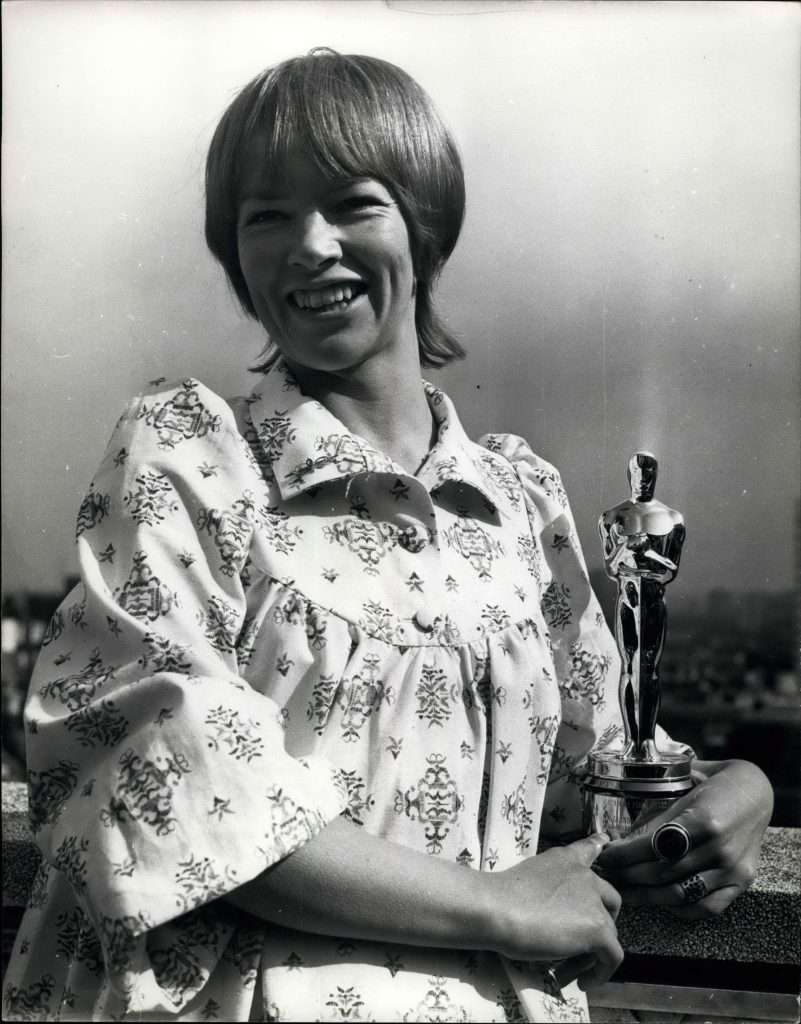

Writer, Larry Kramer, was particularly keen on hiring Jackson to play Gudrun alongside Oliver Reed and Alan Bates. At that time she was well established thanks to her work at the Royal Shakespeare Company but less known in the film world. So it did take some convincing of the studio, but ultimately she was cast and would go on to be the first actress to win an Oscar for a role that required nudity. She did not attend the Academy Awards either of the times she won, later explaining: “I was working.”

Women in Love led to a series of impressive film and television roles. Among them was Sunday Bloody Sunday. Set in 1970s London, after the UK Sexual Offences Act of 1967, which decriminalized homosexual acts in private between consenting adults, the film tells the story of a middle-aged Jewish doctor played by Peter Finch, and a divorced woman in her mid-thirties, Glenda, who are both involved in a love triangle with a younger man. It is one of the most forward-facing films of the era. Director John Schlesinger said of the film: “I knew from the start that it was really a piece of chamber music, that not everyone would appreciate it. But it was a film I believed I had to do. Not wanted to. Had to do.” The film doesn’t judge or even make a point of the fact that two of the lead characters are openly gay. It is a matter of fact, it is just the way they’re living their lives. Schlesinger (Midnight Cowboy, Far From the Madding Crowd) originally tried to cast Finch only to discover that he was unavailable, then went to Alan Bates who was filming The Go-Between. Eventually, Ian Bannen was cast, but in rehearsals he became too nervous about kissing another male actor on screen, fearing it might destroy his career. He dropped out. By this point Finch’s film had been cancelled and so he was available. Sunday Bloody Sunday was the first film pairing of Jackson and Peter Finch, though they share very little screen time. Finch took on the controversial role despite being an established star by this time. He had already done many films that are still considered among the great British films of the period including: Far From the Madding Crowd; The Trials of Oscar Wilde; and The Pumpkin Eater. It would be another few years before his best-known performance as Howard Beale in Network, for which he would win the first posthumous acting Oscar in 1977. The writer of Sunday Bloody Sunday, Penelope Gilliatt, later wrote about Finch as well as his progressive ideas for cinema: “He had seen a lot of Godard’s work for just that reason. The early directors of cinema used the full vocabulary of theatre and camera technique; why lose it? Peter was a rare actor. He is keenly missed.”

As for Finch’s co-star, Gilliatt wrote, “Glenda Jackson was the obvious choice for Alex. Anyone who had seen her work with Peter Brook, or her Ophelia, could have been in no doubt. I once wrote about her that she was the only Ophelia I had ever seen who was capable of playing Hamlet.” Jackson’s performance possesses both incredible emotional strength and vulnerability. She is living in a time that she doesn’t quite fit into: for example, the character, Alex, is not keen on those smoking a spliff around her, nor can she ultimately manage the idea of free love. Alex finds herself in love with a man only really in love with himself, she allows him to visit his other lover whenever he feels like it, frowning at the idea of ever passing judgement. Ultimately, she finds that this is not the life she wants to live, that she can’t quite square it away anymore. The film concludes with two powerful scenes. The first involves Alex finally telling Bob that she has changed, that he should go to America and move on with his life, so that she can get on with hers. The other is the only one in the film between Jackson and Finch, who run into each other outside the home of a mutual friend, having never met but knowing each other intimately. Despite being filled with nerves and expectations, they find themselves rather comfortable. They have shared a love and an experience. In this scene we see the genius of two truly brilliant actors that can tell an entire story with a brief exchange of niceties. It’s a wonderful example for actors, and even better for audiences.

During her Desert Island Discs interview in 1997, when asked about retiring and if she had felt joy or found a sense of satisfaction or achievement in acting, Jackson explained: “Live theatre is at its best an absolutely unique experience for all concerned, I mean that is the audience as much as the actors, but those experiences are rare. What is always frightening and really gives a sense of your own lack of importance in a way is that there’s nothing you can do to guarantee that that will happen.”

She retired from acting completely in 1991. Having joined the Labour Party at the age of 16, it was from the mid seventies that Jackson became more focused on what would become a long and successful political career. Among other things she was on the executive of the National Association of Voluntary Hostels, and spoke at rallies for the housing charity Shelter. Human rights and children’s charities played a big role for her as well as many different causes and movements.

Once Jackson was able to devote herself to politics full-time, she stood as the Labour candidate for previously Conservative Hampstead and Highgate. Despite expectations, Labour did not win in 1992, but Jackson did, narrowly beating Conservative candidate Oliver Letwin. Jackson would later become the first of Labour’s 1992 intake to join the front bench, becoming shadow transport minister in July 1996.

Jackson went on to hold her constituency seat until 2015 despite both boundary and government changes. She was a vocal member against the Iraq War and particularly the impact of the Thatcher years. In the week after Margaret Thatcher’s death, Jackson gave a speech in the commons that encompassed her feelings on the Thatcher years: “Everything that I had been taught to regard as a vice, and I still regard them as vices, under Thatcherism was in fact a virtue: greed, selfishness, no care for the weaker, sharp elbows, sharp knees.” After almost 30 years in Westminster, in 2016 Jackson decided to take the short trip over the river by coming back to acting at the Old Vic, playing King Lear, then she went off to Broadway in a revival of Three Tall Women, for which she won the 2018 Tony Award, and back again to Broadway with her King Lear. A resounding success in both London and New York, Jackson seemed to find something new even in the character that audiences are so familiar with. Keziah Weir, in Vanity Fair, said that Jackson “managed a complexity that few actors can achieve, eliciting a cavalcade of emotions in her audience: delight, sympathy, loathing, and despair.” After her absence from TV screens, Jackson starred in the BBC’s Elizabeth is Missing (2019). Based on the novel by Emma Healey, the film follows Maud, a woman struggling with dementia who attempts to establish what happened to her best friend. Jackson’s Maud wrestles with the loss of memory and understanding of the world around her. It’s an extraordinary piece for an audience to really consider empathy and kindness. Writing for Variety, Caroline Framke said that Jackson “is physically slight but enormously charismatic, with a low rumble of a speaking voice that’s practically a growl.” Next, we will see her in Oliver Parker’s The Great Escaper, alongside Michael Caine. It is true that this version of Glenda Jackson is not the one audience remembered but it is reassuring to know that after such a long time away one can still wield the same power that they had before, and will go on to do so for years to come.