Dea Kulumbegashvili discusses April, her feature film about a Georgian obstetrician who is ostracised for performing illegal abortions.

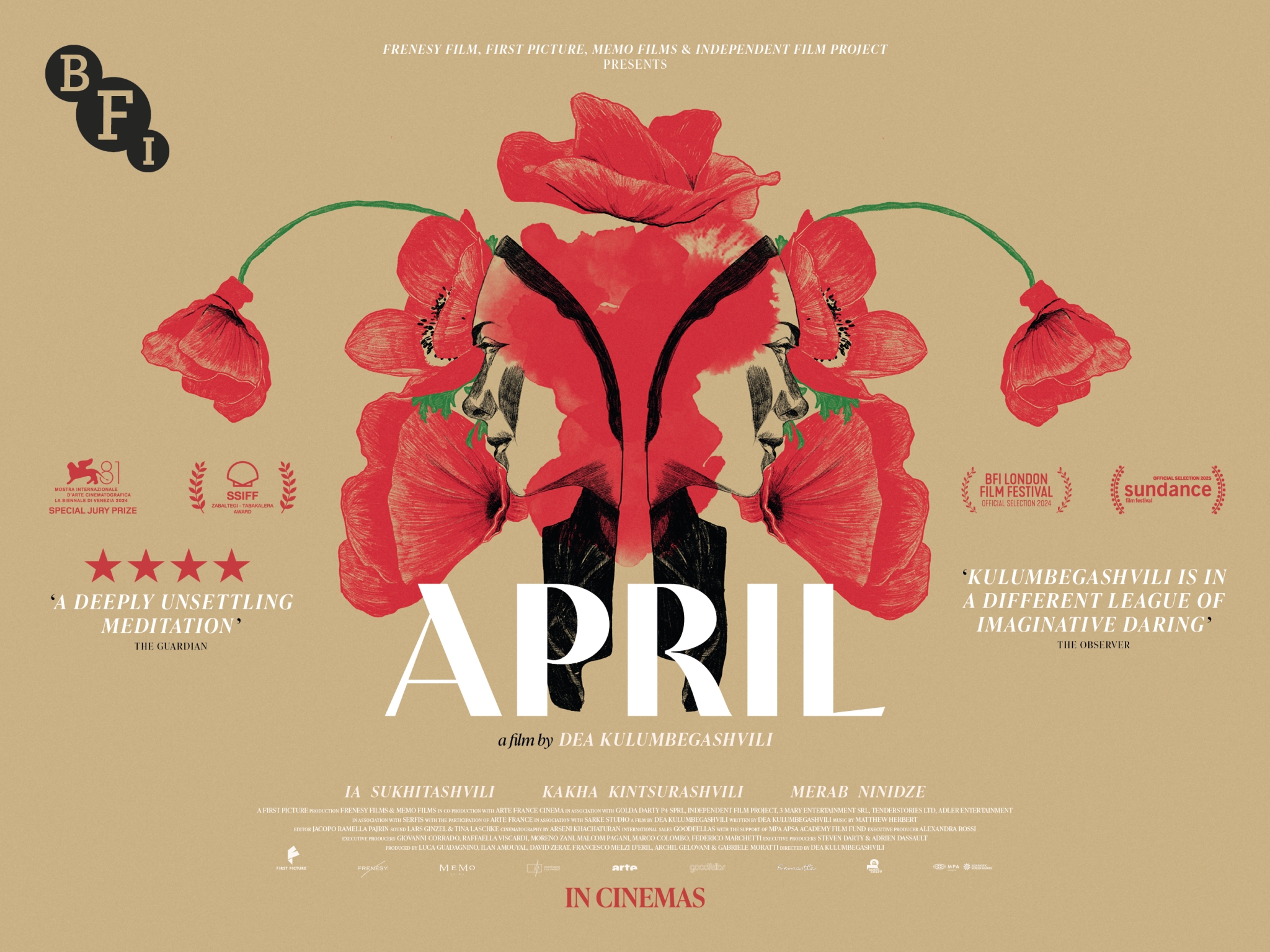

Poppies are a flower that generally grow in disturbed soil. Famously, battlefields soaked in blood and bodies, but also agricultural land overworked by toil and machinery. Where there is damage and death, they thrive. The red flower is a fitting motif in Georgian director Dea Kulumbegashvili’s April. Premiering to great acclaim at Venice Film Festival where it took home the Grand Jury Prize, it is a film in which violence and beauty are exquisitely juxtaposed, and in which fact and fiction germinate together. Its protagonist—if you can call her that, so illusive and spectral is her on-screen presence—is Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili), an obstetrician who, as well as her work in the maternity ward, carries out illegal abortions in the surrounding villages. Abortion, whilst technically legal in Georgia up until the 12th week of pregnancy, is deeply stigmatised in a society which is deeply religious and traditional in terms of gender roles. In the opening scene we watch, from above, a real woman giving birth. When her baby is born a stillborn. Nina faces questioning for her actions outside of the hospital.

Plot and purpose prevaricate in April. Instead, in a slow continuous present, we see, like a tableau vivant of a Francis Bacon, a deeply lonely woman who is a monster to others, and sometimes herself. She drives around, picking up men to sleep with—some of whom treat her with hostility—in between her visits to the villagers desperate for her help. Documentary images, such as sublime, James Benning-esque sequences of fields and rainstorms and two real birthing scenes intermingle with the film’s fictional and unreal elements. At its centre is a deeply wounding scene where an abortion is performed on a deaf-mute girl who has been raped by a family member. We only see her torso, the punctum, the bruise of reality, existing beyond the frame.

A Rabbit’s Foot spoke to Kulumbegashvili about the political realities behind April, contemporary heroism and why she is interested in our boredom.

Kitty Grady: Where did the inspiration to tell this story come from?

Dea Kulumbegashvili: When I was working on my first feature, Beginning, I was working with children and we’d do the casting by going to schools in the villages where we made this film. All of them would come in with their mothers who would come on the shoot each day and I would talk to them in breaks. This film is not only about abortion, but about what their daily lives are made of. And I became preoccupied with the lives of these women, and by the time I was editing Beginning, I knew this would be the subject of my next film, it was a fully formed idea at that point.

KG: Was there something specific anyone said that sparked the idea, or more the general texture of their lives?

DK: Most of them have many children—each of them had more than three or four kids. Some had eight or nine. I have no idea how they managed to get by. We got on to the subject of why they had so many children and we gradually understood that they had never made a decision, it just happened. Some of them who were more brave started to talk about the subject of abortion and how difficult it was to obtain one. One woman who had eight children one day said she had seven, and I asked what happened to the eighth one. It turned out [her daughter] was 15 and had got married. So I enquired into the subject of underage marriage. In terms of statistics, you have the official ones which say there are zero underage marriages. [The government] don’t want to acknowledge it exists. It’s political corruption because they need people in the villages to vote for them so they don’t challenge the traditional way of life where you get married at 15. The vicious cycle continues because even when you talk to these young girls, they don’t know that there’s the possibility of abortion or contraceptives. It’s not possible in the villages.

KG: There’s a line where one of the villagers says ‘we don’t have roads but we have a school that looks like a spaceship’ — I was interested in that tension between people being obsessed with children as the future, but neglect the poverty of the here and now.

DK: It’s a [real] school built by this international organization that goes around Georgia building schools. I could make another film about this. You go inside this contemporary building, which stands in the center of the village, which is in ruins, basically. People don’t have windows—the glass in their windows. There’s real poverty in these villages. No running water, no electricity even. But then you go into this school and there are no books in the library. It’s clinical, clean. The teachers—they will really hate me saying this—they serve the government agenda and they spread this very religious education. The teachers don’t like you being there. They were really aggressive towards us. They don’t want anyone with a camera there.

KG: You were inspired by these conversations with women, but then April focuses on the Nina, an outsider woman who carries out the abortions. How did you create her as a character? I was wondering if you were inspired by the archetype of the witch at all.

DK: I went to several clinics in these rural areas to ask about how abortions would happen if they are practised. I met these doctors who were, for me, what contemporary heroes could be. People who are extremely underpaid. A very qualified doctor in the maternity clinic gets a salary of $200 a month. They work in 24 hour shifts. And if the hospital chooses not to do abortions what do you do as a doctor? They all had different answers. I can’t go into detail because things which are portrayed in the film would not be illegal. But I know that doctors in this region, this willingness to serve their profession goes beyond just what the government tells them to do.

KG: You open with this truly monstrous image of this alien figure which is incredibly striking and scary. Why did you want to open with that level of shock and horror?

DK: It was a lot of shock and horror for me while researching the film. This place, I grew up there and my entire family used to live there. I’m nostalgic of the incredible, beautiful nature and people. But then it has a lot of hidden violence. When we were location scouting we would go from village to village and I would meet a woman with a huge scar on her neck who was very frightened. Every question she would say she needed to ask her husband. It was just so sad. You would see children who had been beaten up by their fathers. I don’t think cinema can change much in places where they can’t even watch films because these women don’t watch films. But maybe the process of making the film could bring some sort of hope, or at least knowing their voices are heard. The women who came to set everyday as extras. It was a day off from their daily life. They would put on make-up and then they would need to remove it. They didn’t need make-up in the film, but I just wanted them to enjoy it. We would give the kids little tutorials with the camera, make them see it was possible to grow up and work in cinema.

Nina’s life gets to the point where it’s unbearable and this creature represents some sort of her desperate need to escape her own life. But then she’s just trapped. The shock and terror of the life people you meet can be difficult to make sense of. You start to have cognitive issues, of how we can allow for these things to happen, but they do.

KG: I was so interested when she said ‘if it’s not me, someone else will do it.’ Did you think about her motivations as a character?

DK: I was looking into what it means to be a hero in the contemporary world. In Greek tragedy, there is an exclusivity in the right to be a hero. It is a destiny. I was interested in the heroes of daily life. Which almost undermines the heroic. It’s important to understand that someone else will do it. It was important for the character to know this and not be thinking about herself as this messiah of sorts.

KG: How did you think about perspective? Our suture with Nina’s POV is often frustrated when we see the back of her head, but then we follow her eye line as she travels, too.

DK: I wanted to viewer to experience the beauty and power of the nature. Despite all the horrors of life there, there is just such beauty which we forget to look at. I talk to children and when I tell them let’s look at a flower they look at me surprised because nobody tells them that they live in this beautiful place. But then nature is also violent in its own way. I wanted the viewer to experience this as almost a physical experience. But then other parts Nina leads us into the scenes where we don’t see certain things that she does. Then we get to this question of what we see and what we don’t see in cinema. Especially in contemporary cinema and television, when a lot of what we watch is on computer screens because of the streamers. We’ve started to reduce cinema to specific ways of telling stories or conveying experiences. Portrait shots and close-ups. But cinema is so much more. It’s a young medium and it’s a very exciting medium. It’s exciting to be testing the possibilities and it’s not always about flying cameras. The possibility is sometimes just taking one specific way of looking at something.

I was looking into what it means to be a hero in the contemporary world. In Greek tragedy, there is an exclusivity in the right to be a hero. It is a destiny. I was interested in the heroes of daily life. Which almost undermines the heroic. It’s important to understand that someone else will do it. It was important for the character to know this and not be thinking about herself as this messiah of sorts.

Dea Kulumbegashvili

KG: I wondered if you could talk about the abortion scene, which we watch in this partial way and the ‘actual’ horrors are beyond the frame.

DK: I wanted to focus on the body and the flesh. I didn’t want a space, per se, with animated emotions. I would rather just have an audience bring their own emotions to the scene. I don’t need to be graphic to show the pain and what this might mean for all of the participants. It’s important for me to understand that we’re desensitized as contemporary viewers. We have seen everything but we also think we need a lot to happen on screen in order to feel something. But I think we should ask ourselves, if we don’t feel something in a moment like this, why? What else do you need to understand the pain of this moment? [The partiality] also shows how it’s almost like a sacred ritual of sorts, where women are doing it in a hidden way and they’re all willingly participating in this crime and all of them are risking their lives doing it. As a filmmaker your place is very modest. You are placing yourself in a very specific moment which is so much bigger than cinema.

KG: There’s a moment where we watch Nina and there’s a clock very visibly ticking behind her. I wanted to ask you about your relationship to cinematic time and the idea of endurance in your film.

DK: I am interested in the subject of time in cinema. It’s so interesting how impatient we are and then five minutes in the cinema are a huge deal for producers when five minutes in life mean nothing. So for me it’s almost like why would you get bored watching something for five minutes? How is it possible to get bored watching a storm for five minutes? It’s also okay to leave the theatre when you’re watching a film. If you get bored and impatient. It’s okay to not watch the film as well. I have seen people walking out from my film. You are looking at the blooming trees and people start walking out. I think that’s so interesting.

April is in UK cinemas now.