The story of Gangs of Wasseypur (2012) was initially pitched to me by two youngsters. It was written to fit the template of Fernando Meirelles’s City of God (2002), which, at the time, had hit cult sta- tus in India. I called that out when I read their pitch and told them it was unoriginal.

Then the two came back to me with a third partner who was from Wasseypur, carrying evidence of all the incidents that were included in the script. I had them research Wasseypur and bring me the entire history of the place. I wanted to restructure the whole storytelling process. Why? A month be- fore in New York City I’d seen Marco Giordana’s two-part six-hour epic The Best of Youth (2003) and also his previous film One Hundred Steps (2000). Both films had an impact on me. It made me want to tell the whole story and not just a part of it—that was what was cinematic. Around the same time, a seminal Thamizh, or Tamil, film (also a movie genre from the southern part of India) called Subramaniapuram (2008) came out. It was by a first-time filmmaker named Mahalingam Sasikumar. These characters reflected how the men here become immersed in fan clubs and mimic the heroes we watch in Indian cinema.

Going through the research they came back with, I thought that these criminals—and their obsession with revenge—were comical. I sat down to write the script in a hotel in Madrid, full of colourful transgender people, and I found myself revisiting Emir Kusturica’s Black Cat, White Cat (1998) and Underground (1995). That mood, coupled with the humour and music in his films, influenced my decision to lead with music in this one. I had been talking to my music director, Sneha Khanwalkar, about how the music that had travelled from India all the way to the Caribbean, through slaves, had come to be known as “chutney music”. Next thing I know, she was in the Caribbean, finding her music. Musical influences were also heavily picked up from smutty North Indian songs that were sung in private when we were kids. A lot of popular music and dialogue from mainstream Indian cinema and soap operas helped dot the period as the story kept moving forward; that allowed us to jump through time periods.

I had never been to Wasseypur. It can be similar to the culture I grew up around in some ways, so I interpreted all of the research based on my childhood and we shot the film exactly where I grew up, too. My partner in crime, my cinematographer Rajeev Ravi, was very adventurous, and a film buff. For these characters’ childhoods, we borrowed from The 400 Blows (1959) and elements of Los Olvidados (1950). Gangs of Wasseypur was formed from a hell of a lot of influences, including more Thamizh films like Ameer Sultan’s Paruthiveeran (2007) and Bala’s Naan Kadavul (2009). And, like I said, The Best of Youth gave me the courage to explore the factual political landscape spanning 67 years in cinematic time.

What came out of all of it was something magical that… just happened. But there was definitely no influence from any Quentin Tarantino film or from The Godfather, which are often what it is com- pared to. To some audiences, the end of Gangs of Wasseypur: Part 1 can seem inspired by Sonny Corleone’s death, when in fact it’s not so at all. Because that actually happened.

My first listed theatrical release was as a writer. It was also a gangster film. Satya (1998) was directed by Ram Gopal Varma and it is still considered a sui generis. Six-odd years later, I shot Black Friday (2004), which was based on the 1993 Mumbai bomb blasts. So by the time the boys from Wasseypur reached out to me, I was already tired of the genre. I didn’t want to do the same work again, but Gangs of Wasseypur actually allowed me to explore and to push that gen- re a bit further than before.

We had ambition, we just didn’t have the money. Both parts together were made for a little under $2 million. I had one unit shooting raw footage of actual sand mining by the mafia and genuine smugglers smuggling coal from the mines. We had to get inside a real quarry, find out the date and time they were planning to dynamite the whole mountain, and wait hours to get a shot of it being blown up in real time by the smugglers. We only had one take and it made it to the final cut of the film in its entirety. It is a key shot in the trailer, too.

And then there was the matter of time. We had to design all action sequences in long single takes. This meant lots of prep before going for a take, unlike in my other films. Also unlike my other films, here I did not shy away from violence—it was all on screen. I usually only suggest the violence (off screen). For Gangs of Wasseypur, we had an action director and did it all in real time wherever possible.

A week before the shoot was set to begin, the original studio dumped us over casting disagreements. We found Viacom in the nick of time. It was new to the market and seeking projects. But the purse strings were tight and we were well aware of that as we had shot extensively for 100 days in the hinterlands, the northern belt of the country. We had no option but to come back with a complete film. I used all the goodwill my father had accumulated over his career as an engineer, setting up powerhouses in the region. My extended family and the crew members doubled as extras. Locations were lifted from my childhood. We took all that we could from everyone we could to make this film. By the end, we had exhausted our resources, people, and goodwill, and it was worth it.

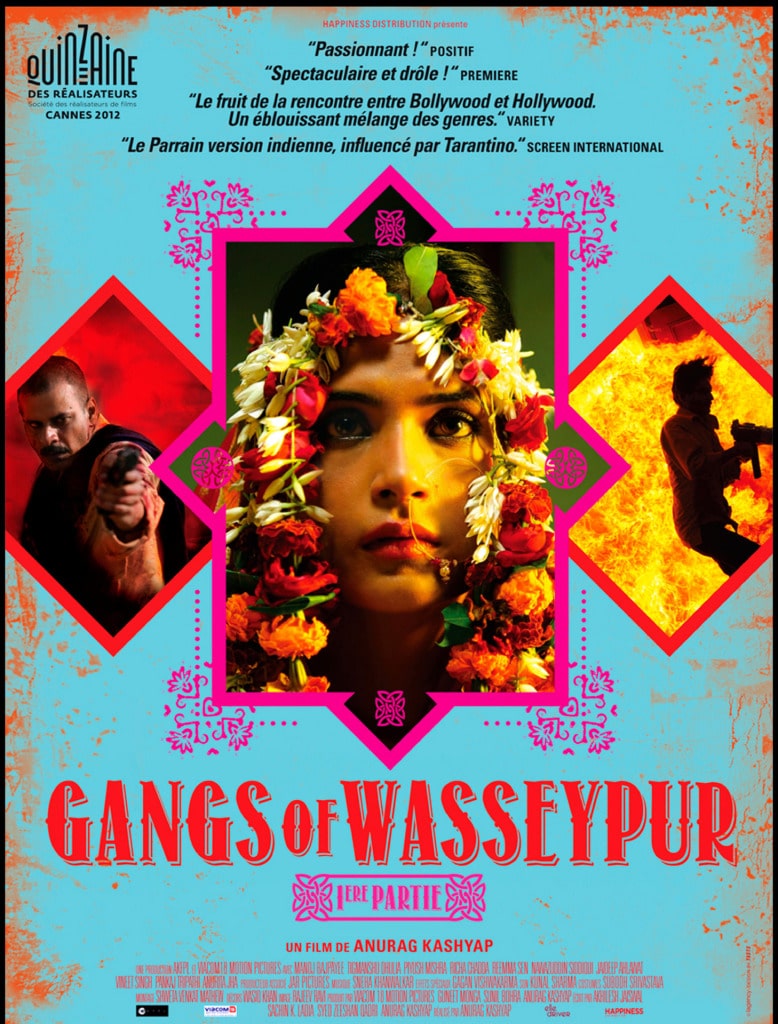

Main image: Still from Gangs of Wasseypur (2012). By Anurag Kashyap.