As Urchin gets set to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival, its main actor Frank Dillane talks class anxiety, working with Harris Dickinson and why we are all just human animals.

Frank Dillane has hurt his shoulder. In order to embody Mike—the protagonist of Harris Dickinson’s directorial debut Urchin—a young homeless man living on and off the streets of London, the actor so keenly adopted the kind of defensive posture someone battling with day to day existence might adapt, that it has left him with long term pain. “There were certain physical things that I wanted to achieve, ways he moved, he walked, he talked. I tried to have this hunch and all of these things that were not Frank,” says Dillane. “I’m still hunched over now, actually, it hurts. My shoulder is pretty messed up.”

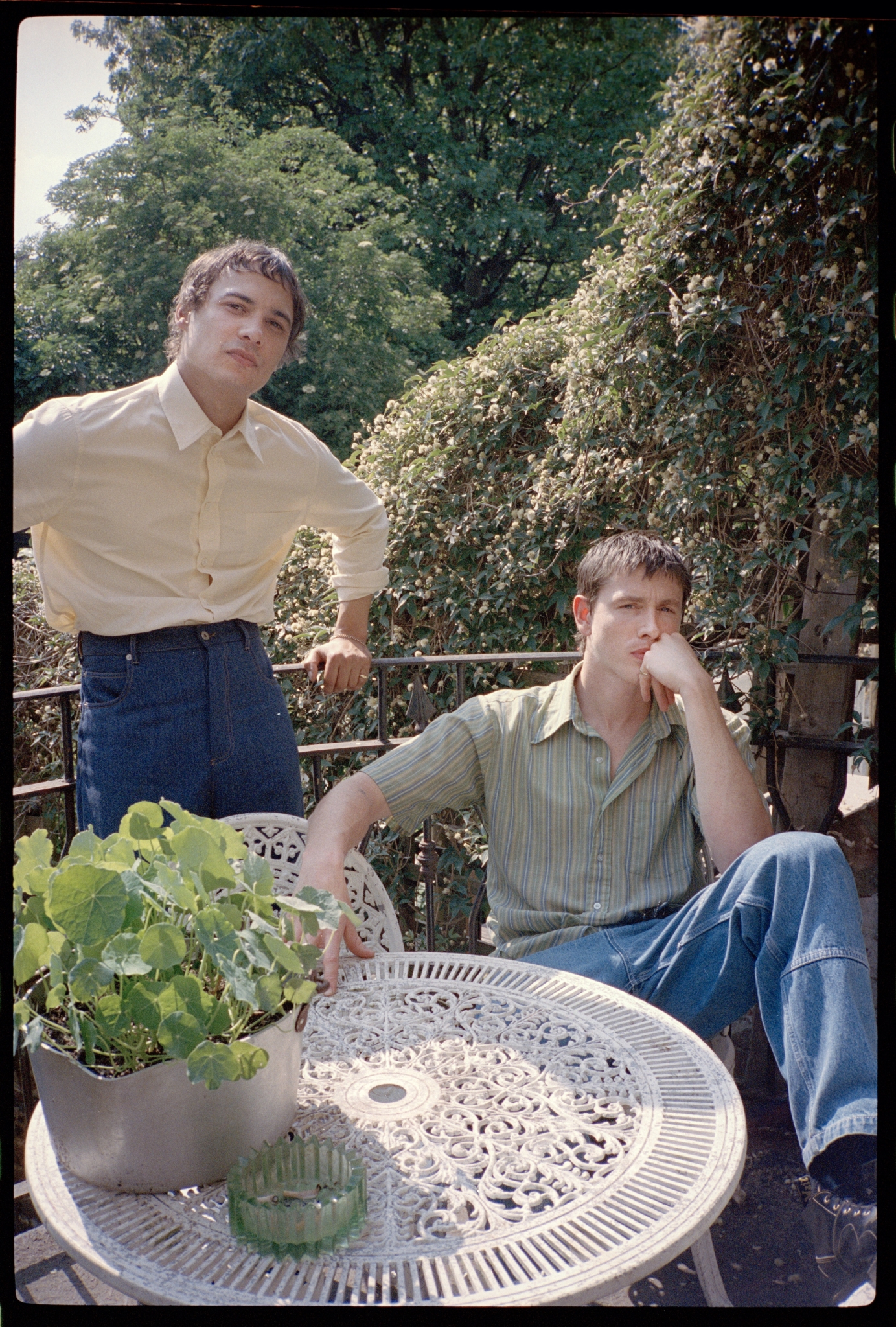

I am speaking to the actor in early May, a couple of weeks before the film’s première at the Cannes Film Festival. We are at Maison Bertaux, Soho’s legendary cake shop and Dillane, who is dressed in skinny black trousers, a striped green shirt and a long black jacket (he later tells me he’s in a band), has come here since he was a child. After chatting with the owners, he orders us a pot of tea, which we drink looking out onto a bright and unusually calm Greek Street. Known for his roles in more gothic titles: Athina Rachel Tsangari’s Harvest, The Essex Serpent, Fear the Walking Dead and Harry Potter (he played a 16 year-old Voldemort), Dillane, 34, is humorous and warm, his disposition much sunnier and sillier than I’d imagined.

The character of Mike is made up of both light and dark shades. At the film’s opening he is an addict on the streets, desperately looking for money and getting into a fight with his fellow homeless friend Nathan (a smaller part played by Dickinson) which leads him to Simon, a man who, offering to buy him a sandwich, Mike assaults and leads him to prison. Out the other side (we experience his time in prison as a journey through the core of the earth) we meet a new Mike: playful and sweet— buying a cactus for his probation officer, giggling with his female colleagues, buying himself snakeskin loafers in charity shops—even if the temperature of his moods still fluctuate. “That’s the scope of us—you, me—I’m here with you smiling, but suddenly I could be really sad and upset,” says Dillane. “I know very little about this, but poverty is difficult and makes you angry.”

Photography by Fatima Khan.

Dillane initially wasn’t sure if it was a role for him. “Harris jokes about me having the script for a long time,” says Dillane. “I was sceptical as to whether we’d get it made, because it’s quite an unusual story and I’m not really a name—and Harris absolutely is—but it is also his first feature as a director.” Dillane grew up in Brixton and then Forest Row in Sussex, attending a Steiner School, an alternative mode of education that is focused on the good “development of the soul.” He was worried his middle-class upbringing (both his parents are actors) and his ethnic heritage (his mother is Jamaican) was at odds with Mike. “There was a big fear in me approaching this character,” says Dillane. “I saw him as this very white, working class guy.”

He perhaps naturally suggested that Dickinson, “a working class English boy” himself might be better suited. “In all honesty one of the first things I said to him was why don’t you play this part?” says Dillane. It’s a question I’m sure many people will ask—somewhat boringly—of Dickinson. “He wanted to direct, and he liked what I was doing. He wanted me to play the part. So once I got over that in myself, and my own fear of working with someone who is such a prolific actor, I used it as a tool—here’s another actor, so rather than give him a really polished performance, why don’t I give him everything?” says Dillane.

For Urchin’s director, finding Mike was not an easy process. “It was so hard,” says Dickinson, when I speak to him in Hackney, the day of our A Rabbit’s Foot shoot. “This role on paper could have very easily been your sort of straightforward cantankerous kind of unruly guy and Frank came in and uncovered all of these areas that were in the script. In the first audition there was a scene where he was asking Andrea about the meaning of life—that scene in the caravan—and he was doing all these kung fu moves and I thought ok, he’s the guy for this. We needed someone to do something entirely unique and that’s what Frank gives.”

With Dickinson, Dillane felt very quickly he was working with a “visionary” (elsewhere, Dillane twice refers to his director as a “sweetheart,” and their friendly chemistry on the day we shoot is like that of joshing old friends). “Harris is a great director. And I knew from watching his short film 2003, I was very aware very quickly that I was going to work with a very serious person and a very serious director,” says Dillane. “He dealt with everyone so beautifully, he was so in charge on set. I was impressed by his ability to make decisions quickly and stay true to the art.” Dillane describes the weekly film screenings that Dickinson would host at his house for the cast and crew of Urchin as preparation. These included Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light and Leos Carax’s Les Amants du Pont Neuf. Dickinson got Dillane involved with the homeless charity Under One Sky, he has a long term involvement with. “It’s a testament to his heart and soul that this is the film he made,” says Dillane.

“Harris wanted to direct, and he liked what I was doing. So once I got over that in myself, and my own fear of working with someone who is such a prolific actor, I used it as a tool—here’s another actor, so rather than give him a really polished performance, why don’t I give him everything?”

Frank Dillane

Playing a character such as Mike, who is orphaned, homeless, and an addict, required a radical leap of imagination. “I’m not sure how to talk about preparation because you can sound a bit mental. But by the time we got to filming, I remember feeling like I’d already shot the movie. It took so much to immerse myself into Mike’s world,” says Dillane. “The main objective was that I had to do his story justice. You have to lend yourself to your character’s philosophy, you have to lend yourself to their belief system. Underneath everything there’s human need and human suffering. It’s very easy for us sitting here in a lovely café to talk about my beliefs, but if your day-to-day is about survival, there’s not that much room for anything other than fight, flight or get fucked. You take away shelter, you take away friends, you can feel quite dehumanised.”

As the title suggests, Urchin is about our inherent creatureliness, and the ways we fend and defend ourselves in the world. “Spiky,” says Dillane of the titular animal. Whilst both director and actor say they weren’t explicitly thinking about current debates around masculinity in the making of the film (“Mike transcends gender,” says Dillane), I proffer that Urchin offers a view of manhood as something refreshingly unsure of itself, but the richer for it. In his temporary accommodation, Mike, who has pipe dreams of owning a chauffeur business, listens to motivational tapes telling him how to get back into the driving seat of his life. He does not actively pursue women, but in a particularly sweet moment describes his ‘type’ as ‘someone who loves him’.

“I found the script so devastating, I found it so sad,” says Dillane. As the film goes on, Mike struggles to stay buoyant. He is down on his luck. Shit hits the fan. Yet there is a residual force of hope that tells us, and Mike, to despair not. “Harris would say to me it’s a comedy and he’d whisper to me in the ear like, you’re going to get this job mate, before we did a take. He always wanted joy, he’d say it’s a good, happy story, it’s not such a tragedy. Harris and I would talk a lot about this human animal. What do we want at any moment? It’s in breath, life, you’re walking around and you feel the rain. It’s those deep feelings—hatred, love—it’s beneath culture, beneath society, there’s this human animal. That’s what I wanted to explore.”

Urchin is premiering at Cannes Film Festival on 17th May. Read our interview with Harris Dickinson here.

Creative direction and photography by Fatima Khan

Creative assistant: Kitty Spicer

Lighting: Laurence Hills

Styling: Karen Clarkson

Grooming: Sky Cripps-Jackson

Videography: Nathalie Ryan and Simao Baroseiro

Additional videography: Luke Georgiades

Special thanks to Molly Baker at Rapid Eye, London. Romilly Morgan, Lauren Southcott, Donna Mills, Emma Jackson

Frank styling: Look 1: Leather T-shirt, jeans and trainers by Bottega Veneta. Look 2: Look 3: Shirt, tie, belt, trousers and shoes by Celine. Socks by Pantherella. Look 2: Yellow shirt, trousers and shoes by Bottega Veneta. Socks by Pantherella.