One of the great character actors of his generation—and Issue 11 cover star—Benicio Del Toro has returned to Cannes for Wes Anderson’s The Phoenician Scheme. But before that, Chris Cotonou joins him in New York to revisit his marvellous career, his extraordinary emergence from Puerto Rico to Pennsylvania and Hollywood. What he discovered is a man who has a sense of humility and self-belief that has made him one of the industry’s favourite leading stars. And in the meantime, he’s planning on getting behind the camera…

It’s 11am on the dot, and Benicio Del Toro is towering over me—wide-grin, wild-hair—in the dimly lit lobby of the Mercer Hotel in New York City. If you want to be left alone, there are few better places than the Mercer. No lavish streetside canopy like the grande dames of Park Avenue. Lights? So low, you’ll be squinting at your server. When I step into the lounge, there are businessmen quietly discussing “dips” and entrepreneurs muttering names like “Beyoncé” over hushed phone calls. For Del Toro, who prefers to live a private life, I imagine him more at home here than Uptown at The Carlyle. But as he greets me with his unmistakable voice—a gravelly hybrid of his native Puerto Rico and America—it can only be Benicio Del Toro: an actor everyone knows, but few really know much about.

In person, Del Toro is as roguishly cool and laid-back as you might expect him to be. This isn’t hard research, but I suspect he’d make a lot of people’s lists of “actors they’d want to have a beer with”. Like Steve McQueen or Charles Bronson, he signals the type of on-screen charisma you instinctively know is a part of his personality—and it is. He also has a very busy mind, which makes him digress into offbeat topics and references, from the pop singer Bad Bunny, whose recent album he is a fan of, to baseball metaphors. We spoke about bands such as The Rolling Stones and The Velvet Underground, and how he likes to ride motorbikes and scuba dive in California. Acting is his purpose but it’s also a job, he explains—a job he takes seriously. And by all accounts—from the awards to critics and audiences—a job he does supremely well. After leaving Del Toro, I was reminded of my favourite uncle—ready with the paternal wisdom of a man who’s been through the ringer, but still carries a lightness that makes him easygoing and soulful. Perhaps that’s why it comes across on screen so easily.

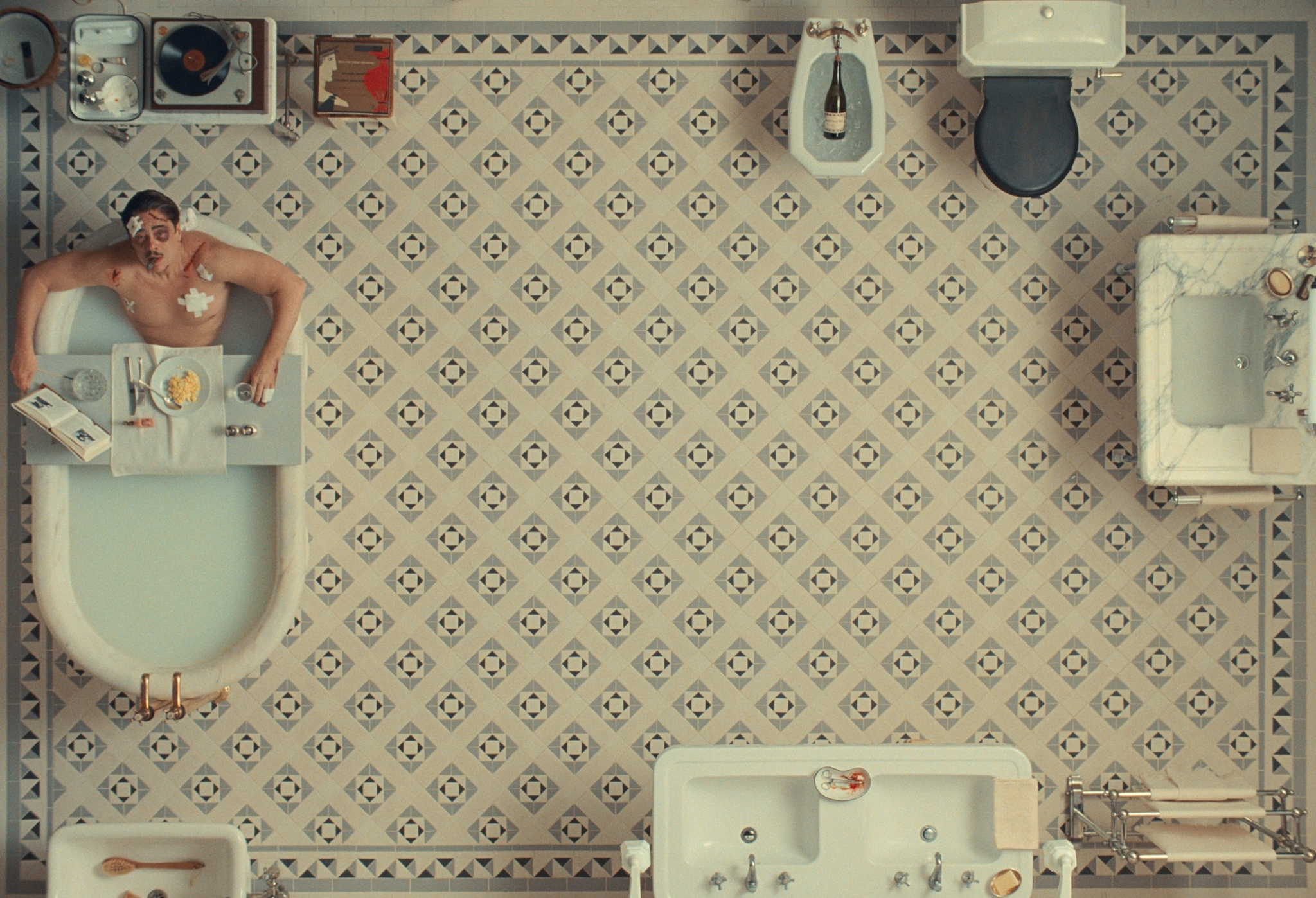

He’s right to be in good spirits when we meet. Wes Anderson’s upcoming black comedy The Phoenician Scheme (2025), which Del Toro has a leading role in, has been confirmed for the Official Selection at the Cannes Film Festival. He’s in New York to do some press, he explains: “If you love Wes’s previous films, boy, you’re gonna love this.” It’s the second time he and the director have worked together after The French Dispatch (2021), which came as a surprise for Del Toro, who has built his reputation on serious, morally ambiguous characters in Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects (1995), Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario (2015), and Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic (2000), for which he won an Academy Award. “I loved his films, but I never thought I would fit into his world,” he smiles.

Del Toro is excited to return to Cannes, a festival he has a multifaceted relationship with. “Cannes is important for cinema but it’s also been a huge part of my career,” he explains. He reels off a long, decades-spanning list of movies that brought him to the French Riviera—even if he, himself, was not competing for prizes. He finally won the Best Actor Award in 2008 for Che on the Croisette. In 2010, he served as a Main Competition Jury Member, and in 2018, he was appointed president of the Un Certain Regard Jury. He’s no stranger to the red carpet. “I remember when I was there for The Usual Suspects, staying in this tiny hotel and looking out of the window out to sea. The film wasn’t even competing. But I thought, ‘This is it’. Cannes is the Olympics of Cinema.” He leans in smiling. “Plus it’s a lotta fun—don’t forget about the fun!”

For The Phoenician Scheme, Del Toro is in the leading role as the brilliantly named Zsa-zsa Korda, a businessman who appoints his only daughter, a nun, as sole heir to his estate. Naturally, chaos unfolds in Anderson’s unique breed of humour. Korda has more in common with his darker roles than is immediately obvious, Del Toro explains: “It’s a human story. Korda wants to restore his love and relationship with his daughter. It doesn’t matter how strong the man, or woman, is. The ground shifts.”

Del Toro, who throughout our interview touches on ideas of morality, redemption, and struggle, has been on a quest to understand himself through his characters. “Some people are bad and nothing can redeem them,” he says. “But as an actor, you have to play it and not judge it.”

But I suggest to Del Toro that these ideas, and a sense of justice, have deeper roots in his life that have informed the types of roles he chooses. Both his parents were lawyers. And as a child, he

When Del Toro was nine, his beloved mother passed away. It was a great tragedy of his life, and the effects still reverberate. He recalls how his mother took him to painting classes as a child. It became his first creative pastime, and it remains a connection to her that he continues to dabble in. “Through painting, I began to learn how to express myself,” he says.

Six years on, he joined his father and brother in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania. Small-town America was now home. Compared with San Juan, it was a more “muted” environment for Del Toro, but he found common ground with his peers through music. “Rock and roll were my vitamins,” he grins.

The way Del Toro describes his teenage years, I picture him as an angsty jean-jacketed youth hanging out with friends in parking lots, smoking and listening to hard rock music. He was the outsider in his family, he admits—and certainly the rebellious brother. “I wasn’t academic like him,” he explains. “He could engage in adult conversation. I had too much energy. As a young man, I was more cocky than ambitious. My family was always concerned about me.”

It was through basketball, not cinema, that Del Toro excelled in high school (he’s taller than he looks on-screen). He considered playing in college. But to appease his family, who encouraged him to pursue a “conventional” job, he enrolled on a business degree at UCSD in San Diego, California. It was there that he switched to acting, “only because it made my schedule free to do things I was into at the time, like scuba diving, riding my bike, or just sitting around daydreaming,” he laughs. After performing in a bilingual version of Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879), where his teacher encouraged him to draw on his personal experiences, acting became his life’s purpose. “When the play came to Joseph Papp’s theatre here in New York for a college theatre tournament, I got a thrill. Then I realised I could do it. I was in the heart of American theatre. I had to be here.”

Committed to learning the craft, Del Toro came to New York aged 19 to study with the Circle in the Square Theatre School, not far from where we’re sitting. Then, there was his formative experience learning under Stella Adler in California in the 1980s, where he landed a scholarship. Adler, a woman deserving a place in the Mount Rushmore of theatre, a mentor to Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, and Elaine Stritch, was famous for her Adler Technique: a method rooted in imagination and purposeful action. She also had a personal soft spot for Del Toro, recognising his raw, malleable energy. “She was so wise. When I look back, the experience was a big lifesaver. It made me think that my dreams could happen.” Here, he was finally learning a craft and began reading voraciously to learn more. “Her technique remains the foundation of my acting.”

He speaks about Adler, then in her 80s, with reverence and a little fear, as if she’s suddenly going to appear from behind us and scold him. “She got me on the stage good,” he laughs. He recalls an incident that displays her genius and her drive to perfection. While portraying a junkie in one scene, she corrected his slumped, hopeless posture. “She stopped me and said, ‘Put your shoulders back. You’re not playing a bum. You’re playing a man who uses his body to tell society that there is something wrong with it.’ She forced you to look at your character and ask what they said about society,” he says.

Why the switch from theatre to the screen? He states the obvious. “If you have Cubby Broccoli on the phone saying he wants you for a James Bond movie, and when you do it, it’s like, wow, that’s good, and the money’s good, you do it,” he says. “Some of my favourite actors at the time started in the theater, like John Malkovich and Raul Julia. Bottom line is: acting is acting, whether you are doing it on the stage, the big screen, or on TV.”

“Cannes is important for cinema, but it’s also been a huge part of my career.”

Benicio Del Toro

The toughest battle was at home. Raised in a hard-working Puerto Rican family, where his father, and especially his godmother, Sarah—who, like Adler, was a very influential woman, and perhaps a matriarchal figure, in his life—objected to his newfound acting career. It took years for them to accept his decision, and Del Toro admits that in the early days, he fought for their approval. “If I got a part, I called them first and gave them the news like a dog bringing a bone back. But, let me tell you, when you start and get a few parts, you think you’ve made it. And then years follow with one strike out after another, and then suddenly, maybe, you get a part again. Fourteen months without work? They saw it differently. They were worried I wasn’t gonna eat.” It was a struggle to the top, especially when the carousel of TV roles and bit-parts as thugs and drug dealers dried up. There were moments he considered calling the dream off—even while working in Hollywood. He recalls how his father and brother, both well-meaning, tried to stage an intervention and persuade him to return to college. But then The Usual Suspects happened.

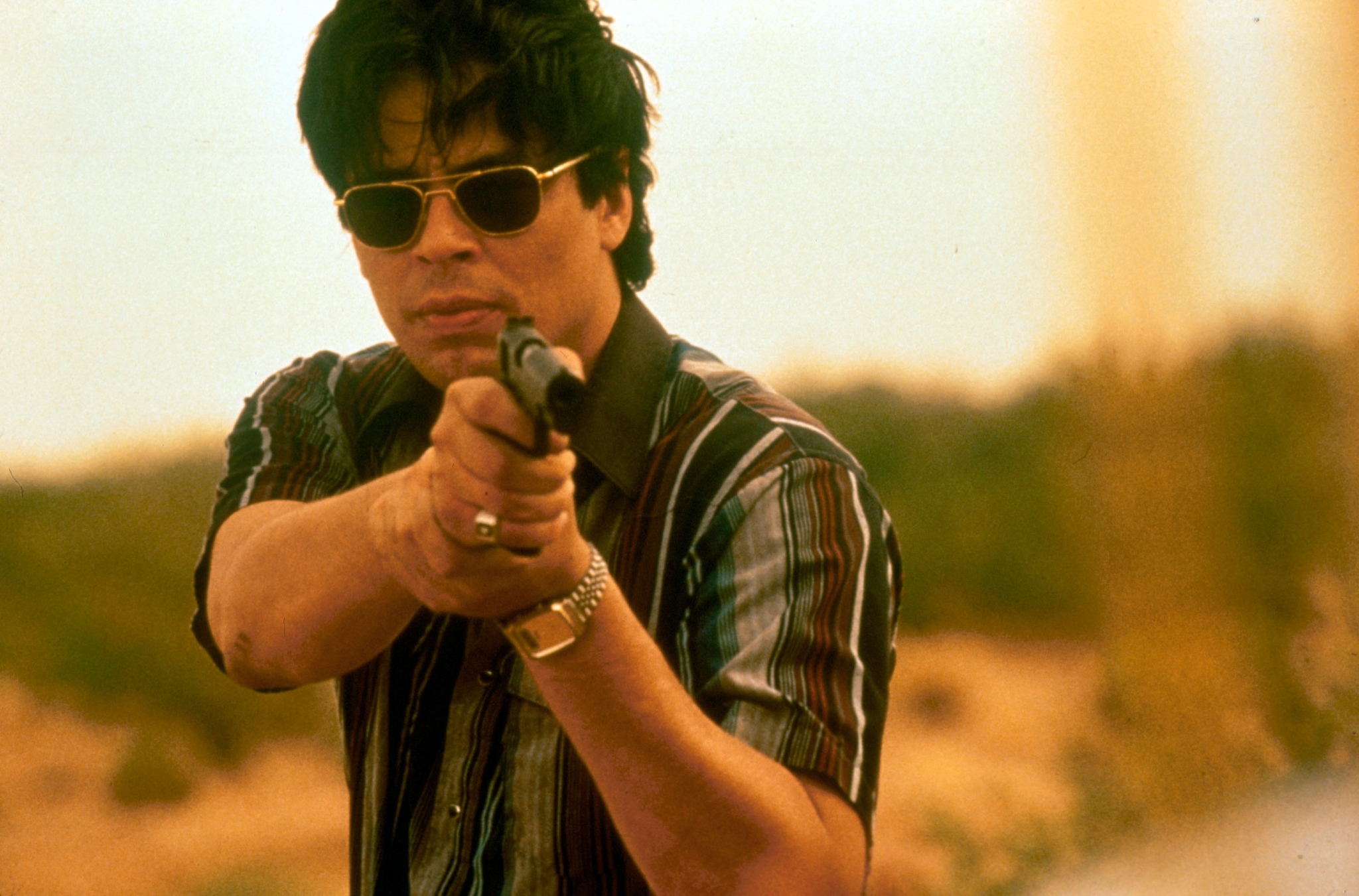

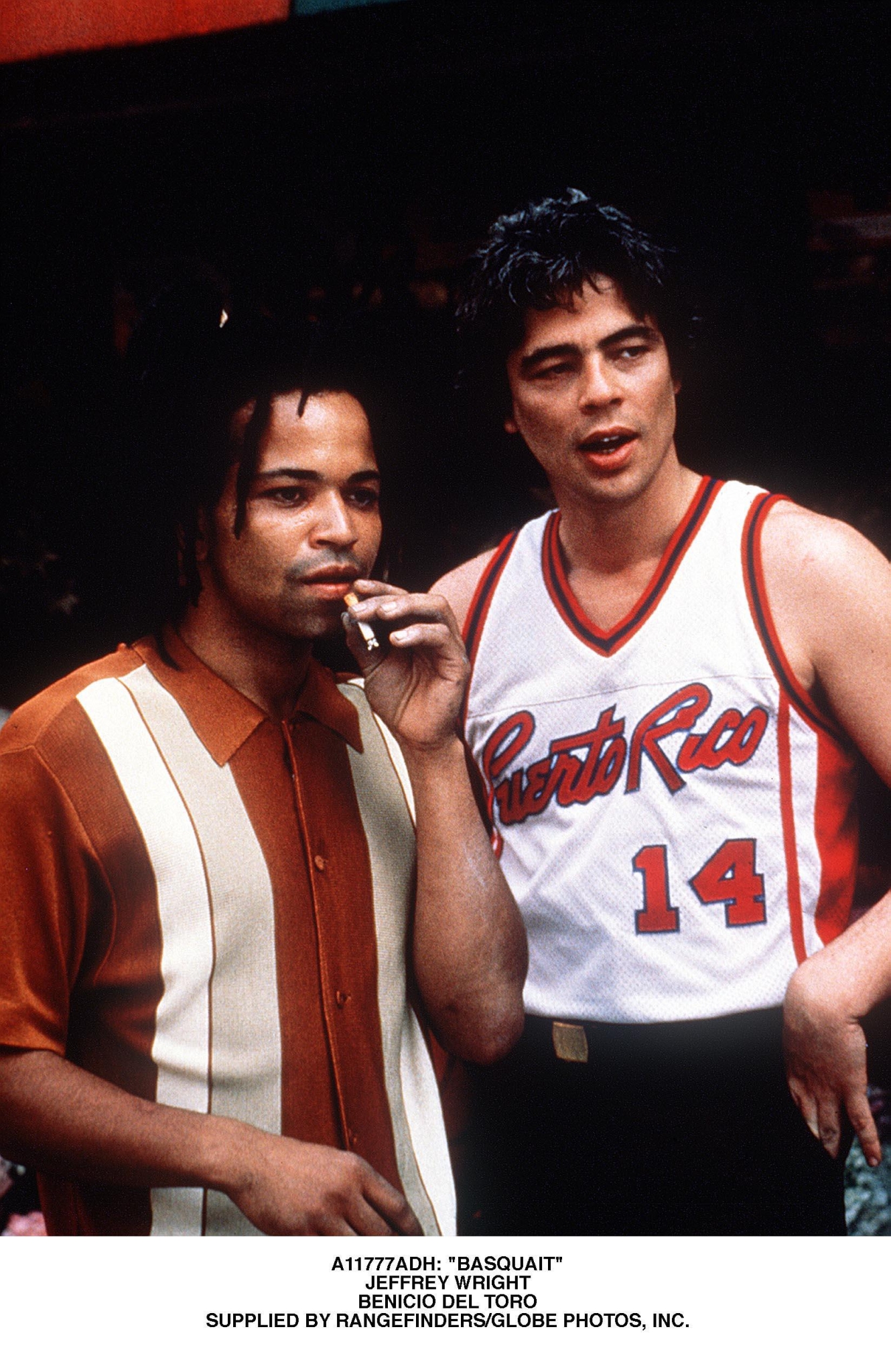

“That was the moment it felt like Hollywood, or the industry—I think that is what people call it—said, ‘Oh, he’s an actor’,” he explains. Bryan Singer’s clever 1995 crime thriller, famous for its Keyser Söze twist, is also memorable for Del Toro’s performance as the mumbling, wisecracking crook Fred Fenster. It’s a role so impressive, it announced him as an exciting young character actor—a scene-stealer—and roles followed with Abel Ferrara, the artist Julian Schnabel, and, in his most cult performance and one of my favourites, as the mad Dr. Gonzo in Terry Gilliam’s 1998 adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. This fruitful period hit its forte in 2000 with Steven Soderbergh’s Traffic, where he took home an Oscar (by now, there was no need for family interventions) for his role as Mexican cop Javier.“ Traffic, for example: “Steven Soderbergh and I worked on parts of the story and character, and that’s something I enjoy. Maybe some of the decisions about the character come from logic, your life, or from understanding the human condition.

As you get older, you get better at that.” This brings us to Del Toro’s opus role, years in the making: Che Guevara in 2008’s Che. There are fewer more human, or ambitious, stories than this one.

Growing up in Puerto Rico—a territory of the USA since 1917—Del Toro was raised with no real awareness of the Cuban Revolution. “But I remember, if you saw a picture of Che somewhere, you knew he was the bad guy,” he says. “But when I was in Mexico shooting Licence to Kill, I saw a picture of Che smiling, and I was like, ‘Wow—this guy is smiling like a good guy!’” He leans in. “You can’t judge a smile… but you can. And then I bought a book of his letters he wrote to his aunt, father, and mother…and I realised he has a sense of humour. He’s a human.” When producer Laura Bickford sent Del Toro Jon Lee Anderson’s seminal 1997 biography Che: A Revolutionary Life, he started shopping it around Hollywood.

Eventually, Steven Soderbergh agreed to direct and the rest is history. The result is a thrilling two-part epic that is meticulously orchestrated entertainment, but grounded in realism. Did he ever leave Che behind? “Of course, I had to,” he replies. “You know, it’s work, Chris. I stay focused all the way to the last moment. And I remember the last day of shooting… We were in Bolivia, by a river. Steven looked at me and said, ‘That’s it’.”

“I remember, if you saw a picture of Che somewhere, you knew he was the bad guy.”

Benicio Del Toro

As I end a question on nostalgia, Del Toro pauses for a moment, laughs, and then politely says, “I don’t look back. You’re making me do it.”

To the present, then. Along with The Phoenician Scheme, he is promoting Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another (2025), in which he has a supporting role. “I’m lucky to have worked with both masters in such close proximity. And they come from two sides of the filmmaking spectrum.” He describes the theatrical, dialogue-driven style of Wes, and Paul’s instinctive, documentary-like filmmaking. “I tell you one thing they have in common aside from their last names,” he laughs. “They don’t give up until they have the perfect shot.” There are other acting projects—no longer any shortage of those for the veteran Del Toro. The past decade has been characterised by much lighter material: a Star Wars series and three Marvel films among them. Has the character-actor gone mainstream? “As an actor, you want to do it all.” And even with the Oscars, the blockbusters, the fame, and the fortune, there’s still a subconscious feeling that the party might someday end, he explains. “I’ve had lulls and periods of rejection. Because actors are trained with the sense of endless rejection, your subconscious realises when it’s a good time to capitalise.” The difference with Del Toro is that he’s still the best thing in everything he does. But there’s another path on his mind: directing. “Maybe it’s time for me to get behind the camera,” he says.

Having worked his way through a storied pantheon of directors, from Abel Ferrara to the Andersons, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Ken Loach, and worked on blockbusters as well as having produced for Che, The Wolfman, and 2023’s indy Reptile, Del Toro has always had a strong hand behind-the-scenes of his projects—he filmed a segment in 2012’s 7 Days in Havana and back in 1995, he directed a young Matthew McConaughey and Valeria Golino in a short film titled Submission.

Del Toro’s disciples have searched all corners of the internet, on forums and illegal pirate sites, and cannot find it. Incidentally, Del Toro tells me, neither can he: “I’ll have to dig it up!” He references John Cassavetes, another actor-director, as an influence and then thrillingly describes the opening to 1971’s Minnie and Moskowitz by heart, like reciting from a storyboard. “Maybe directing a full length feature film is going to be a nightmare by why not?” As we say goodbye, Del Toro asks me what I want to do in my life. I’ll spare the details here, but he takes a genuine interest, sharing pointers. Like Stella Adler, he’s a natural mentor. “I’m going back to my high school in Pennsylvania on Thursday,” he says, as we share our final pleasantries in the hotel lobby. “I’m excited to be addressing the kids at my high school.” Human stories—they often come full circle. And maybe, behind the camera, the best of Del Toro is yet to come.

The Phoenician’s Scheme will premiere at Cannes 2025 and will be released in the UK on May 23rd and May 30th in the USA.