I’ve been speaking about my gaze a lot lately. You guessed it: they don’t ask about the colour of my eyes, nor about the nature of the feelings that animate me, or if I am cynical, perplexed, or full of hope. If my gaze comes under question, it is to understand its gender. Am I looking at the world through a woman’s eyes – the female gaze, to use the popular expression? Especially since I treat clandestine abortion in an intimate way, and I film my actress’s naked body without eroticising her – unless when she chooses to eroticise herself. I can say, therefore, that from the first time these questions were posed to me (and it began early on) that it is a feminine gaze. I affirm this with a certain confidence, a joy that holds it to higher levels.

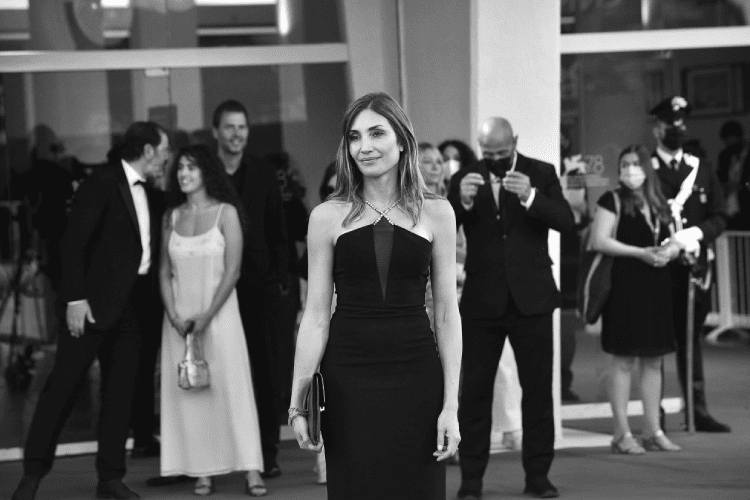

But as the question is repeated to me, it begins to resonate in different ways. It takes on different tones. I have the strange impression that the question is in motion, that by the way I approach ‘feminine’ I am forbidden to anything else. So my gaze narrows, and so does its scope. I am no longer the fruit of a culture, an experience, or my cinephilia. The word ‘woman’ seems to swallow up the rest. It is a woman’s look. Period. And this creates suspicions. Perhaps it is my kind that feels rewarded the day I am honoured with the Golden Lion in Venice. The woman slowly takes precedence over the one who creates, on all the dimensions that make the gaze so complex. People no longer talk about my gender to underline its particularity, they refer me to it; they assign it to me. A women’s film for women, I heard the day before yesterday. Here, we put the film in a box, and my vision with it.

Yet I directed L’Évenément hoping that the female gaze could bridge the gap between the sexes. That this experience would involve the senses, and invite everyone to merge, for a hundred minutes, into the body of this young girl abused by the law. That is the strength of cinema, it seems to me: to take the viewer out of their own frame and deliver them to other experiences. Then, to discover if they are the same when the lights are switched back on. Probing their human gaze and trying to find out if they retain a resonance within themselves, something of a path travelled together, hand-in-hand. My own gaze is now lost on the horizon. It seeks a happier day in the distance, when the genre of an artist will be an outdated question.

—

On me parle beaucoup de mon regard ces derniers temps. Vous l’aurez deviné, on ne m’interroge pas sur la couleur de mes yeux, ni sur la nature des sentiments qui l’animent, on ne veut pas savoir s’il est cynique, perplexe ou plein d’espoir. Si on interroge mon regard, c’est pour en connaître le sexe. Est-ce que je porte sur le monde un regard de femme, un female gaze pour employer l’expression qui se popularise. D’autant que je traite de manière intimiste l’avortement clandestin et que je filme le corps nu de mon actrice sans l’érotiser, – si ce n’est quand elle l’érotise elle-même. Je peux donc dire dès la première fois où l’on m’adresse cette question (et elle survient très tôt) que mon regard est féminin. Je l’affirme avec une certaine confiance, une joie même de porter haut ce regard.

Mais à mesure qu’on me répète cette question, elle se met à résonner autrement, elle se teinte d’une tonalité différente. J’ai l’impression étrange que la question se déplace. Que par cette façon d’aborder le « féminin » on me défend d’être autre chose. Mon regard rétrécit et son champ avec. Je ne suis plus le fruit d’une culture, d’un vécu, d’une cinéphilie. Le mot « femme » semble avaler le reste. C’est un regard de femme, point. Et ce regard là crée des suspicions, évidemment. C’est peut-être mon genre qui est récompensé le jour où on me remet le Lion d’or à Venise. La femme lentement prend le pas sur celle qui crée. Sur toutes les autres dimensions qui font la complexité d’un regard. On ne parle plus de mon genre pour en souligner la particularité, on me renvoie à lui, on m’assigne à lui. Un film de femme pour les femmes, ai-je même entendu avant hier. Voilà qu’on met le film dans une boite et mes yeux avec.

Pourtant j’ai réalisé L’Événement espérant que mon regard de femme pourrait faire le pont entre les sexes. Que cette expérience impliquerait les sens et inviterait chacun à se glisser, pendant une centaine de minutes, dans le corps de cette jeune fille malmenée par la loi. C’est la force du cinéma, me semble-t-il, de sortir le spectateur de son propre cadre et de le livrer à d’autres vécus. Pour voir s’il est tout à fait le même quand la lumière se rallume. Sonder son human gaze et chercher à savoir s’il garde en lui une résonance, quelque chose de ce chemin parcouru ensemble, main dans la main. Mon regard maintenant se perd à l’horizon, cherchant au loin le jour heureux où le genre de l’artiste sera une question dépassée.

—