In American Gigolo (1980), Richard Gere’s Julian Kay and Lauren Hutton’s Michelle weren’t just characters; they were style blueprints. In this essay, stylist Olivia Pezzente revisits a cinematic moment when fashion didn’t chase trends, when a red Bottega clutch could speak volumes, and style had the power to seduce without explanation. In a culture saturated with content, speed and influencers, has costume design lost its grip on our imagination?

Richard Gere as Julian in American Gigolo, 1980.

As “Call Me” by Blondie plays in the background and Richard Gere drives down the California highway, it’s not the glistening water that catches my eye, or the way his coiffed hair is being gently tousled by the wind—or even the hum of his Mercedes engine under a hazy L.A. sky. No. What hits first is the contrast of his red polka-dotted tie against a freshly pressed baby blue shirt, tucked perfectly under a relaxed suit.

When Paul Schrader, director of American Gigolo, appointed the master Giorgio Armani as head of costume design, he gave him a single mission: “The clothes are the character.” They were one and the same. Julian Kay wasn’t just wearing Armani—he was Armani. Every look was precision storytelling: icy blue to signal detachment, neutral knits to soften his seduction, loose tailoring to suggest power without effort. He sold fantasies for a living, and his wardrobe was the pitch deck.

Richard Gere as Julian in American Gigolo, 1980.

But it wasn’t just about good taste—it was about mystique. Julian’s clothes offered clues but never full answers. He was luxurious but unknowable, sensual but controlled. There was an intentional distance in his dressing: the monochromes, the sharp lines, the deliberate lack of noise. Like any great character, he invited projection. You could never quite place him, and that’s what made him magnetic. Armani didn’t just dress Julian—he sculpted a façade. One that hinted at danger, desire, and the discomforting blend of surface and substance. His suits were shields, and his style? A smokescreen.

It was decided that this character—this man—could only be remembered as a true icon if the costumes fully embodied him. And they did. So where have all the style icons gone?

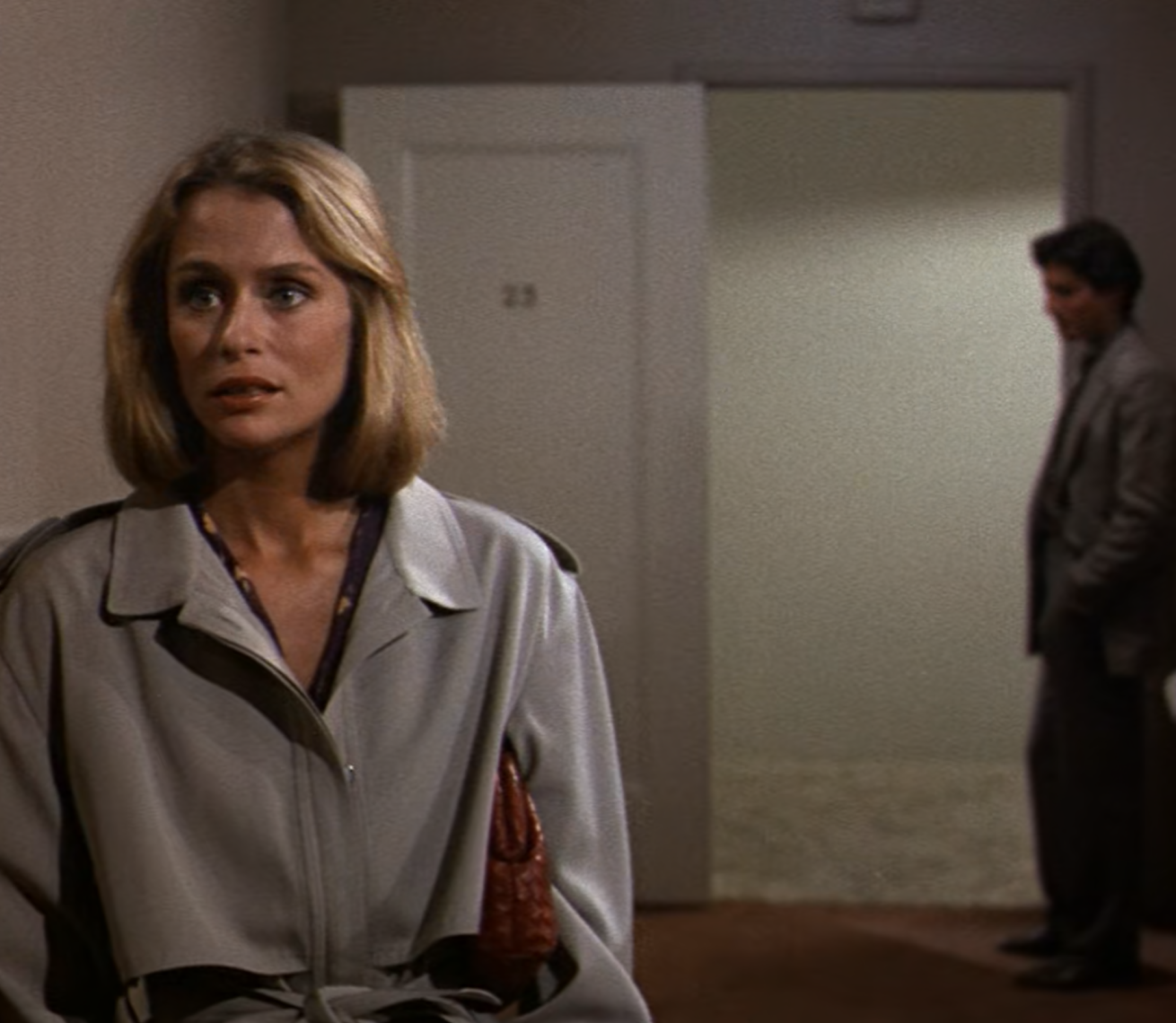

Before the age of influencers, people looked to cinema not just for plot or escapism, but for full, life-altering inspiration: a new way to talk, to act, to dress. When Lauren Hutton walks into Julian’s apartment with her red woven Bottega clutch, I didn’t pause for a second to consider that stalking a gigolo might be a red flag. All I thought was: What is she wearing under that trench? And how am I going to afford that Bottega bag?

Bottega Veneta named the bag the Lauren 80 fifty years later. It appears multiple times in the film, never ceasing to be a main character in every scene it graces. Hutton, who recently starred in Bottega’s Craft Is Our Language campaign, proves the enduring power of character styling. The campaign emphasises the brand’s simplicity and quiet strength. Ironically, it feels more cinematic than most recent films.

When Lauren Hutton walks into Julian’s apartment with her red woven Bottega clutch, I didn’t pause for a second to consider that stalking a gigolo might be a red flag. All I thought was: What is she wearing under that trench? And how am I going to afford that Bottega bag?

Characters in movies used to feel like their own personal brands. But what do film characters stand for today? Why aren’t these new-age icons as memorable?

This is more than nostalgia. It’s a call to arms. We need to stop reducing film to just a plot engine and start revaluing the aesthetic language that once defined cinema: costume, set design, light, shadow, texture. These elements weren’t just background—they were part of the script. Today’s films feel flatter not just because of the stories, but because we’ve forgotten that cinema is a visual art. It’s about dreaming in full colour. And yes, that includes a perfect lapel.

We bring these visual codes into our lives, whether consciously or not. I can trace my fixation with crisp white shirts and architectural silhouettes directly back to watching L’Eclisse. Monica Vitti’s wardrobe—designed by Milan born Bice Brichetto—wasn’t just beautiful; it was a visual extension of her character’s disconnection and quiet longing. The minimalist cuts, the monochromes, the impeccable tailoring, they spoke volumes. It taught me that style could express alienation, desire, and mystery without uttering a single word. Cinema used to show us how to move through the world. Now? It’s been flattened into Pinterest moodboards and merch drops.

Monica Vitti as Vittoria in L’Eclisse, 1962.

I have what I call “outfit memory.” I can recall any outfit, at any time, worn by my close friends on any day. But ask me to name a single iconic look from a recent film—not a vampire movie or a period drama, and I draw a blank. Has the styling budget gone missing, or has the styling itself forgotten to make us care?

Giorgio Armani created a style icon in American Gigolo—and in doing so, shifted the way men viewed suiting. He moved us from rigid tailoring to something more relaxed, sensual, and deeply personal. And we believed it, because we could see it. Richard Gere’s teal trousers and snug henleys are forever etched in my brain. They weren’t just wardrobe choices. They were world-building.

So yes, let’s bring back the styling budget. Let’s dress our characters in looks we won’t just remember—but ones we’ll fantasise about long after the credits roll. And if we can’t do that – then at least bring back a man in mini shorts.

Lauren Hutton walking in Bottega Veneta’s SS17 and 50th anniversary of the brand campaign. Hutton is wearing the Lauren 80 bag, named after the legacy the bag made in American Gigolo.