Author and journalist Michele Masneri on the experience of meeting Arrigo Cipriani at Harry’s bar in Venice, and how the legendary lawyer-turned-barman and restaurateur drove him at full speed through the streets of La Serenissima.

In Italy, for centuries, being a lawyer—or Avvocato—has been considered a noble title. By studying law, mothers and grandmothers would say (while worrying about your future) you’d have “all the doors open”. Because of this, in combination with an extremely complicated and Byzantine legal system, I believe that in Italy there is a higher density of lawyers than in New York. In the social ladder, as a country that loves its titles, and refers to everyone as a ‘Dr’ as long as they have a degree (even if they don’t; particularly in the South), being a lawyer is a sign of superiority. Italy had a very famous lawyer, The ‘Avvocato’ Agnelli; the tycoon of both Fiat and elegance.

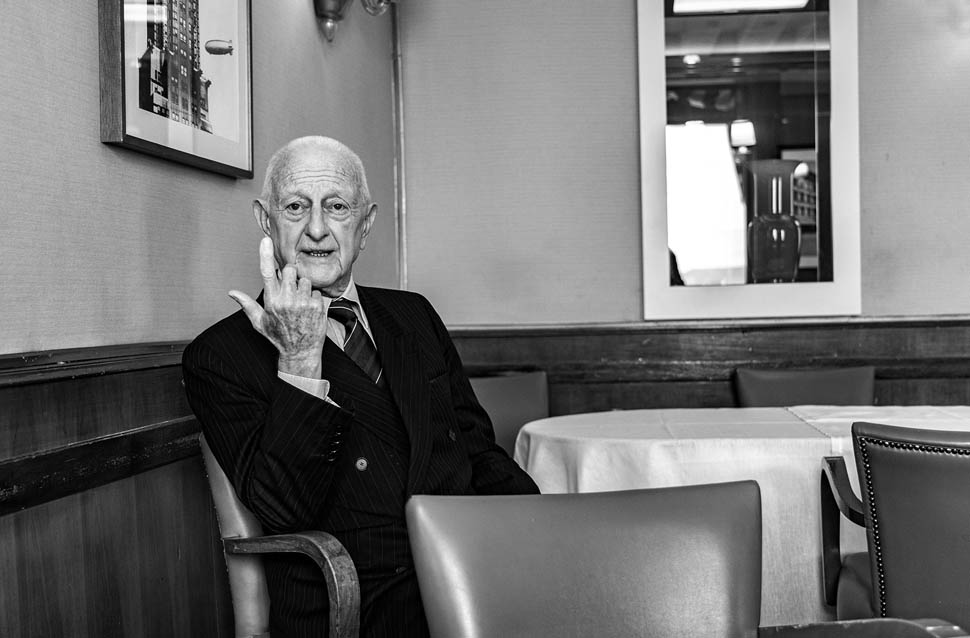

When an Italian magazine asked me back in 2014 to interview Arrigo Cipriani, the legendary owner of Harry’s in Venice, I discovered, among many other things, that he too was a lawyer, and that he liked to be referred to with his title.

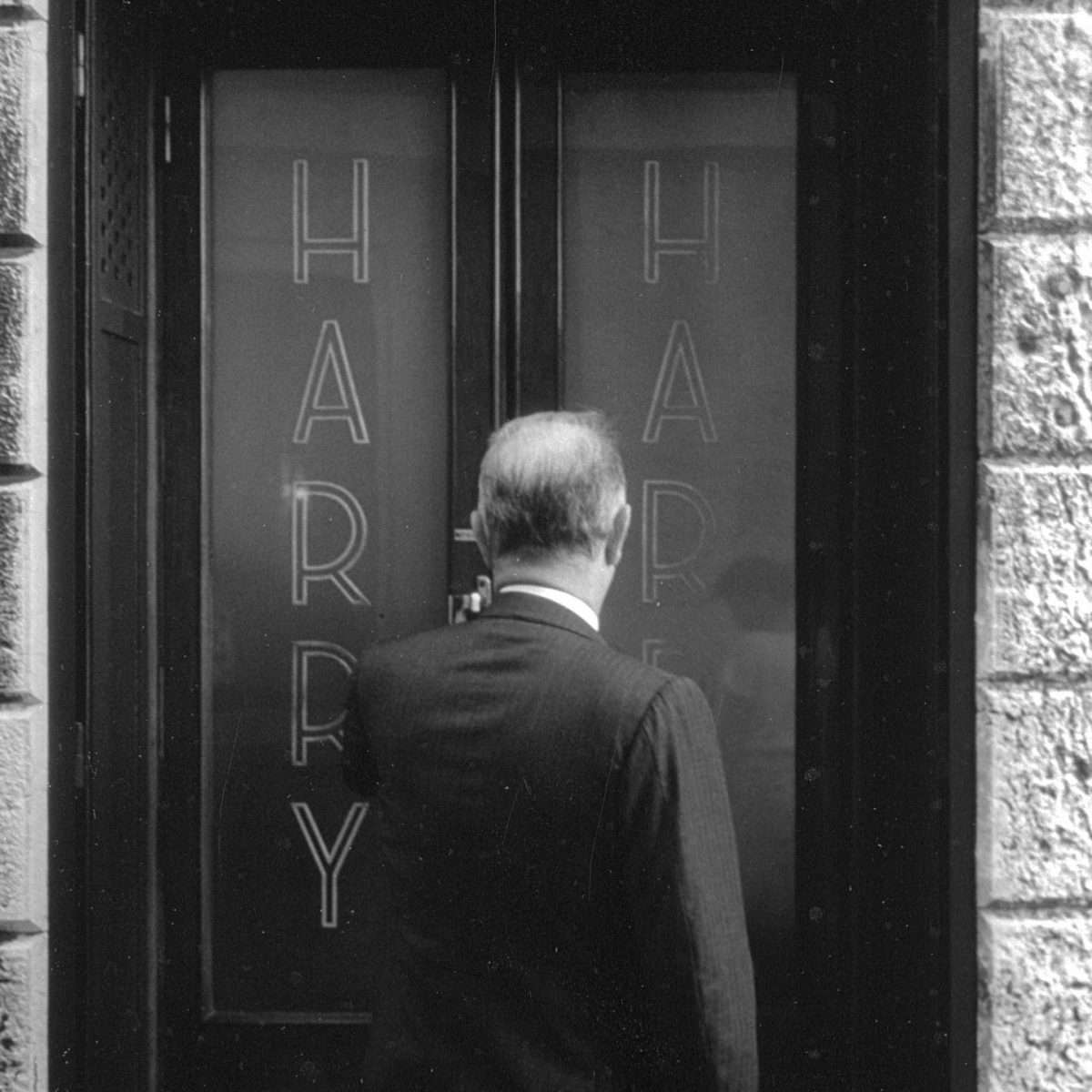

Arrigo earned a degree in Law, even though he barely practised this forensic profession—much like Gianni Agnelli. So, how did I end up with the Avvocato Cipriani? I departed from Rome on the fast train, and there I am, entering a small, barely signposted room, and inside I noticed the hallmarks of the legend: the dimensions; with everything made on a smaller scale, short and round tables and chairs that have pinpoint angles to guarantee a comfortable and refined seat, with the arms plumbing along the sides and the forearms resting on the table at a ninety-degree angle. The plates and cutlery were also smaller, and featured dessert forks “…They are the right measurement, and they turn in the right way,” and the Martini cocktail here, another “workhorse” of the place, gets served in a tiny “60ml” liquor glass. “The goblet doesn’t make sense,” Arrigo used to say “because its function is to keep heat away from the hand, which has been overcome by the invention of the freezer.” It is a minimalist spread imagined by his father Giuseppe, who founded the bar: “He hated the acrobatic barmen and all the over-the-top gestures, the big glasses, the sommelier stands, the affectations” he told me. “There is nothing yet to be invented in the cocktail art, my dad used to say; the base ingredients are the usual five: vodka, gin, rum, cognac…and rum. The classic beverages are the same ones. You just have to mix them well.”

That said, Cipriani Sr went on to invent two classics: the Bellini, that was baptised here in 1948, and the Carpaccio, invented in 1950. “The names were taken from two Venetian exhibitions of the time, one on Giovanni Bellini and the other on Vittore Carpaccio” Arrigo admitted distantly, whilst downstairs a group of Americans ate and drank as though they were involved in a sacred ritual.

‘As we were no doubt speeding, Cipriani told me how his fate as a lawyer was a surrender’

Michele Masneri

After we ate, I felt a bit tipsy from the small Martini: that pleasant drowsiness from day-drinking, while Arrigo gulped down some mineral water. He said that he quit drinking. How long has it been? I asked. “Since this morning,” he replied, in his usual wit.

He predominately spoke to me about his father. “My dad Giuseppe,” he remembered, while we were sitting on a impeccable table on the first floor of his bar, surrounded by the yellow linen cloths and the candid uniforms of the waiters, “…was born in Verona in 1900, the last of eight brothers, from a very poor family. He then migrated to Germany, and came back to Italy in 1914 when the First World War started. He became a trainee pastry chef, and then a waiter, then again a Maître d’. Following the advice of his employer, he became a hotel barman, as he “had the right tone of voice, inspired sympathy, and knew some languages”. “Eventually,” Arrigo added, “he founded Harry’s bar using Harry Pickering’s name, a scion from Boston who was out-of-touch with reality and was sent by his family to Venice to cure an initial phase of alcoholism, but destined to become the namesake of a legendary bar.” And so, Harry’s bar was born on May 31st in 1931, “…and one year later I arrived,” said Arrigo, “I should have been called Harry as well, but the law at the time did not allow foreign names.”

Indeed, it was the time of fascism. I remembered that the ‘other’ Avvocato (Agnelli) was born just one year before Mussolini’s rise to power in Italy, in 1921, and that he lost his father at a very young age due to a tragic accident. Agnelli’s dad, Edoardo, was also born in Verona, although it was difficult to imagine such different realities: Arrigo’s dad being extremely poor, and Gianni’s father being the son of a prominent Italian businessman.

The heir to Fiat, I remembered, had really been raised by his grandfather, the legendary Senator Agnelli, as well as his mother. Despite the huge family fortunes, he had decided that he too would achieve the title of Lawyer.

“Now come with me, I have something to do,” Arrigo suddenly motioned, interrupting my thoughts. So we set off on foot with a broad military step (even though he referred to himself as lazy). We passed the bridge of Calatrava—a bridge that in Venice is often discussed—built recently by the Spanish archistar Santiago Calatrava. It has a beautiful oblong shape, even if the Venetians denounce such things as infiltrations. “And above all it turns red in summer! Touch it! Touch here,” and he actually made me touch the hot bronze of the handrails. Then, back to Piazzale Roma, one of the few places where Venetians can park their cars. At a high price, of course.

Arrigo Cipriani. By Valentina Gallimberti Ballarin.

There, Avvocato Cipriani took possession of his silver Mercedes AMG 6.3, in which we sped towards the mainland. “I have an appointment in Mestre,” he told me. It is quite unusual to go by car to Venice, and very unusual to have Arrigo Cipriani as driver. It is even more unusual to be transported by him through Venice in a car whose speedometer shows 220km per hour. Mr Cipriani did not fear speed cameras.

In that short stretch of the road, nailed to the red leather seats, as we were no doubt speeding, Cipriani told me how his fate as a lawyer was a surrender: “My father definitely wanted me to be a lawyer,” he said. So, the young man was sent to Padua to study law. The only problem was that he liked women and cars more than books, and while he did graduate, he didn’t like the practice much. “I worked at an old studio, which was exactly where the first floor of Harry’s bar is today,” he mentions. Indeed, in 1960, Harry’s incorporated what had been Arrigo’s lesser-loved law firm to the space. “Since you will never become a great lawyer, it is better if you stay at the register,” his father would tell him, without realising that his son would become the most famous Italian barman of all time.

As Arrigo spoke, casually holding the steering wheel with two fingers—like all real drivers—I remembered those reports that Truman Capote (one of my favourite writers) did in the sixties. They were typed from Italy for Vogue America, while Diana Vreeland was still there. I thought of one report in particular, about Agnelli, of whom Capote remembered as a reckless guide. Agnelli was in fact famous for loving danger in all forms. He often took the place of his driver and willingly smashed cars, as well as jumping directly from a helicopter on skis or into the sea. All this, even though his father died in a plane crash. I don’t know why I didn’t ask Arrigo about Agnelli, who I also knew had been to Harry’s many times. Agnelli said he had accepted the fate of the industrialist, even though he would have loved to do something else, like being a journalist, for example. Instead, I asked Avvocato Cipriani if he ever wanted to do something else himself, and his answer, while driving faster and faster: maybe to kill his father…psychoanalytically? “Perhaps out of laziness, I never really wanted to.” And while Venice flew at great speed outside the windows, I remembered the words of Capote: “If you are next to a lawyer, it’s better to hold on fast, especially on the bends…”