As the Eve Babitz vs. Joan Didion discourse rages on, Katie Driscoll pens an ode to the fizzy excesses—aesthetic and alimentary—that consumed Babitz’s life and work.

The bloody mary’s at Musso & Franks are, I find, exactly like Eve Babitz once wrote, “unparalleled”. The bloody mary’s at Musso & Franks can “cure anything”, at least for me, where jet lag and familial conflicts are concerned. Plus the waiters are young and cute.

It’s a million degrees, my first time in LA and the orange trees are swaying, the bougainvilleas blossom underneath the spring sun, and the palm trees are here too, exotic monuments, standing as stoic as Redwoods, except with twice as many stories to tell.

Later I go to Hollywood Forever Cemetery, where Eve Babitz, Patron Saint of young girls eager for a good time, is buried. I’m surprised to see her mausoleum in the crypt filled with her books and a little business card bearing the AA serenity prayer instead of, say, a tin of sour cream, or boxes of tea cakes and chocolate rabbits (which she dedicated her first book, Eve’s Hollywood to, along with “watercress and cheese pie, anything vinaigrette and decent wine”).

I have always been drawn to Babitz in a molecular, kindred way, for her fizzy excesses and penchant for sharing everything, when I discovered her, I read that we were exactly the same weight and height (140lb, 5”7), a silly little detail but one that enamoured me, for she was not the petite waif of so much art and literature. If I was going to write a book of dedications, mine would almost certainly be eight pages long, too (mine would read: “to snowdonia truffle cheese, mortadella and sauerkraut”).

Eve Babitz was the First Woman in her own Garden of Eden. A groupie adventuress-artist of the Sunset Strip, she came of age in “West Hollywood in the sixties when life was one long rock n roll” a universe where men smelled like champagne and had liquid bronze eyes and shrimp cocktail and oysters flow as readily as the drugs (alcohol, speed, LSD, mushrooms, mescaline, cocaine, Percodan and Demerol “for fun,” codeine and Fioranol “for cramps,” Quaaludes and Mogodons when available).

Like her protagonist Jacaranda in Sex and Rage, Babitz also believed in “bold adventuresses, cigarettes” and “suffered from one too many of anything”.

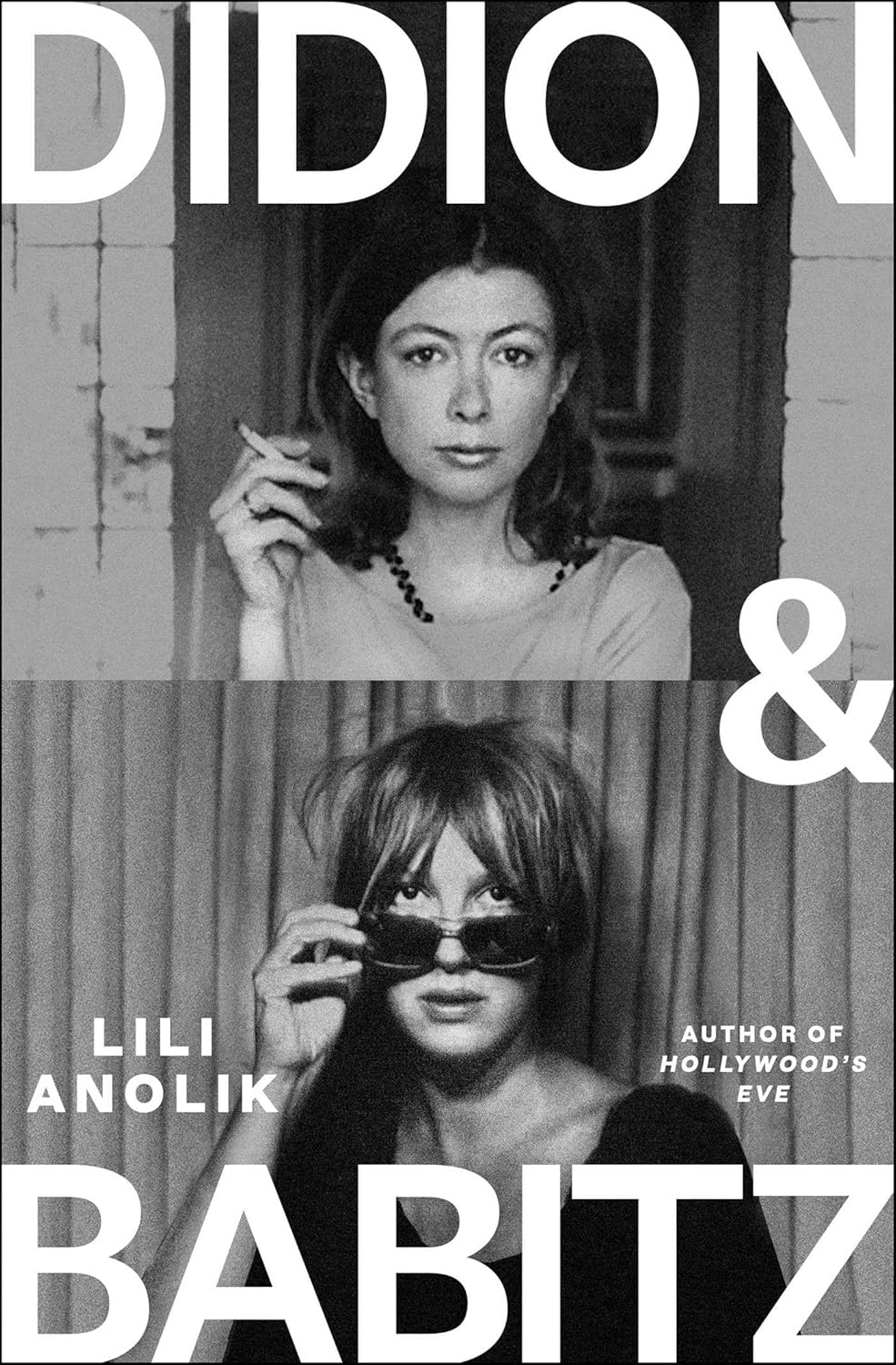

Lili Anolik, Didion & Babitz (2024)

It’s this hedonistic indulgence, this impulse toward excess, which gripped me first and foremost. Not just how hot she was (“I looked like Bridgette Bardot”), nor how privileged (goddaughter to Stravinsky, daughter of a Fox-contracted musician father and artist mother, a child of the surf and sun, educated under the gaze of Rudolph Valentino’s Sheik, the mascot of Hollywood High), but just how bodily Eve was, a born sensualist. I also know what it’s like to be a slave to pleasure and skinny boys with long hair (two exes had told me I was visceral).

With Eve, you’re at home. You’re reading her and it’s like having drinks, catching up with a friend, one who lives for making you laugh and saying what’s exactly on her mind, like how she’s an “appreciative student of men’s legs”, or, as written in her essay “My life in a 36DD bra”, “I always knew that if I ever really wanted anything, all I had to do was lean forward slightly”.

With Eve as guide, LA is a city laid out like lace and full of angels with attitude, where beauty is power, fun is always the criteria, “the object of desire” as she writes in the essay “Nicholas Cage”. Instead of being immersed in the “business of living”, she’s out prowling as a groupie at the Troubadour or gorging herself on salami and artichoke hearts by the Greek Theatre.

For Babitz, food is Proustian: in Eve’s Hollywood, her 1974 debut, a speedy collection of autobiographical vignettes as the glamorous daughter of the LA Wasteland, she remembers the “Will Wright’s chocolate burnt-almond ice cream cone” she was eating the first time an older man tried to pick her up on the street age 14, the frozen Look bars “which we shattered against the counter in their wrappers and ate the splintered pieces which were heaven” when skipping school. When she’s mortally depressed she spends all of her money on champagne cocktails, “it seemed the only sensible thing to do”.

But it isn’t just food and booze. There is “no such thing as enough” when it comes to cocaine, quaaludes are “made for sex and sex is our art”. She reveres beautiful people, men and women alike. The lover to whom she lost her virginity has a voice that was “exactly like chocolate, it was like chocolate chocolate chocolate”. You can practically hear her moan straight off the page and into your ear.

In comparison to, or perhaps, in spite of Babitz, there’s Joan Didion. And although the Madonna/Whore complex is infuriating (or in this case, the saint and the saucepot), Lilli Anolik’s new book tracing their “friendship”, Didion&Babitz, pits the two against one another once more. And they were never more different in their approaches and attitudes than in their appetites— whether in regards to sex, food or ambition.

Didion, as we know, taught herself how to write as a journalist and novelist, by copying out Hemingway, all taut, concise, strict sentences, “An attack of vertigo and nausea does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968” she wrote of herself that year, “I was absorbed in my intellectualisation, my obsessive compulsive devices, my projection, my reaction formation my somatisation”.

Her persona, the ice-cold sphinx. Married to one man her whole life (with whom she had a long working relationship, the writer John Gregory Dunne), Didion’s straightness, her bourgeois domesticity, is anathema to Babitz’s freewheeling, free loving. (Babitz once stated that Didion had taught her about Spode china).

My copy of Slouching Toward Bethlehem is pristine, mint condition, and my copies of Babitz books are dogged, with scribbles in the margins, coated in wine spillages, chocolate fingerprints. Pages loose from usage. It seems a fitting symbol for the women themselves.

Babitz’s prose is effervescent, phantasmagorically vivid, practically edible, infused with a passion, a texture, a colour, with sentences like “last week, I woke up at 8am thinking about taquitos”, or “being in bed with Jim was like being in bed with Michelangelo’s David, only with blue eyes”. Another lover is her “very own St Sebastian.” Men have voices “like mangos, sweet with exotic impulses” and eyes like “gold lagoons”. She describes Doris Day’s voice as “like cake and vanilla and cherries”. About herself, she says “I look as though I’ve been roused from a bed of bon bons, ostrich feathers and tuxedo highballs”. She thinks of nothing but “banana raisin cream pie” while driving to meet a new lover. Looking at the pink sky and lavender-walled garden post-swim, post-fuck, the only thing to top its brilliance off would be “shrimps and roast beef”. You can certainly never imagine Didion waxing lyrical about taquitos being better than heroin, or the very thing that would make you move back to LA from Rome (as Babitz did).

Excess, Babitz’s raison d’être, seems to Didion a nuisance. Didion describes the “sushi for twenty, steamed clams, vegetable vindaloo and many rum drinks with gardenias for our hair” when she enters the studio and world of The Doors, not with thrill but admonishment. Didion called The Doors “the Norman Mailers of the top forty”, but she would not deign to call Jim Morrison CUTE in all caps, as Babitz was prone to in her writing (the essay “Polar Palace”) or proposition Jim within three minutes of meeting, as Babitz admitted to- no, bragged. Babitz was a born groupie, being amongst musicians was in her blood, but for Didion, “Spending time with music people was confusing, and required a more fluid and ultimately more passive approach than I ever acquired”.

My copy of Slouching Toward Bethlehem is pristine, mint condition, and my copies of Babitz books are dogged, with scribbles in the margins, coated in wine spillages, chocolate fingerprints. Pages loose from usage. It seems a fitting symbol for the women themselves.

Repose and a type of feline discipline also extended to her physical stature and the way she carried herself. “I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests”, she had once, infamously, written in Slouching Towards Bethlehem. And it’s Didion’s size, that of the petite waif, at 5ft and 90lbs, which Anolik brings us back to, something which allowed her to be a part of the Boys Club of serious (male) artists, something Babitz took umbrage with. An eviscerating letter from Eve to Joan, one that burns with loathing, opens Anolik’s book: “Would you be able to write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening?” Babitz could never walk into a room without being noticed, as photographer Julian Wassar said, as a “piece of ass”; Didion’s unassuming stature allowed her to be taken seriously, while Babitz’s sex appeal saw her writing dismissed as the frothy gossip reserved exclusively for “women’s” magazines like Vogue and Ms.

Eating dinner at another one of Babitz’s haunts, the Chateau Marmont, (“a bastion of grace” she called it in essay “My God, Eve, How Can You Live Here?”). I smell the lavender and jasmine in the warm air. The inside of the Marmont is warm and amber like brandy. I have taken an edible and proceed to gorge myself on caesar salad and truffle fries and smoked broccoli and salmon with lentils, and dessert, chocolate mousse, Eve’s favourite (“devastating”), and of course, champagne cocktails. I’m transfixed by the blonde MILFs that pepper the surrounding tables with their Botox and veneers. Strewn within them are anemic looking rockstars and silver foxes with cravats. Woody Harrelson, or his doppelganger, sits with a husky puppy with sapphire eyes. Bogart in A Lonely Place plays on a screen in the bar, muted, while a live piano tinkles someplace else. LA is the town of the eternally young, and it’s this eternal adolescence that Babitz captured so well in her writing.

Babitz “only wanted to stay young forever and fool around”; Didion writes of herself as a “recalcitrant 31 year old child”, one “too often frightened of migraine and failure”. Joan may have created a whole new form and way of writing, the individualistic and hyper stylistic voice of New Journalism, but Babitz didn’t need to mythologise or self-create—she was utterly herself, flaws and all, with an appetite that never waned, a hunger for life that’s still shocking and delicious. “Once it is established that you are you and everyone else is merely perfect, ordinarily, factory-like perfect… you can wreck all the havoc you like” she once wrote, you can imagine, with a devilish smile.