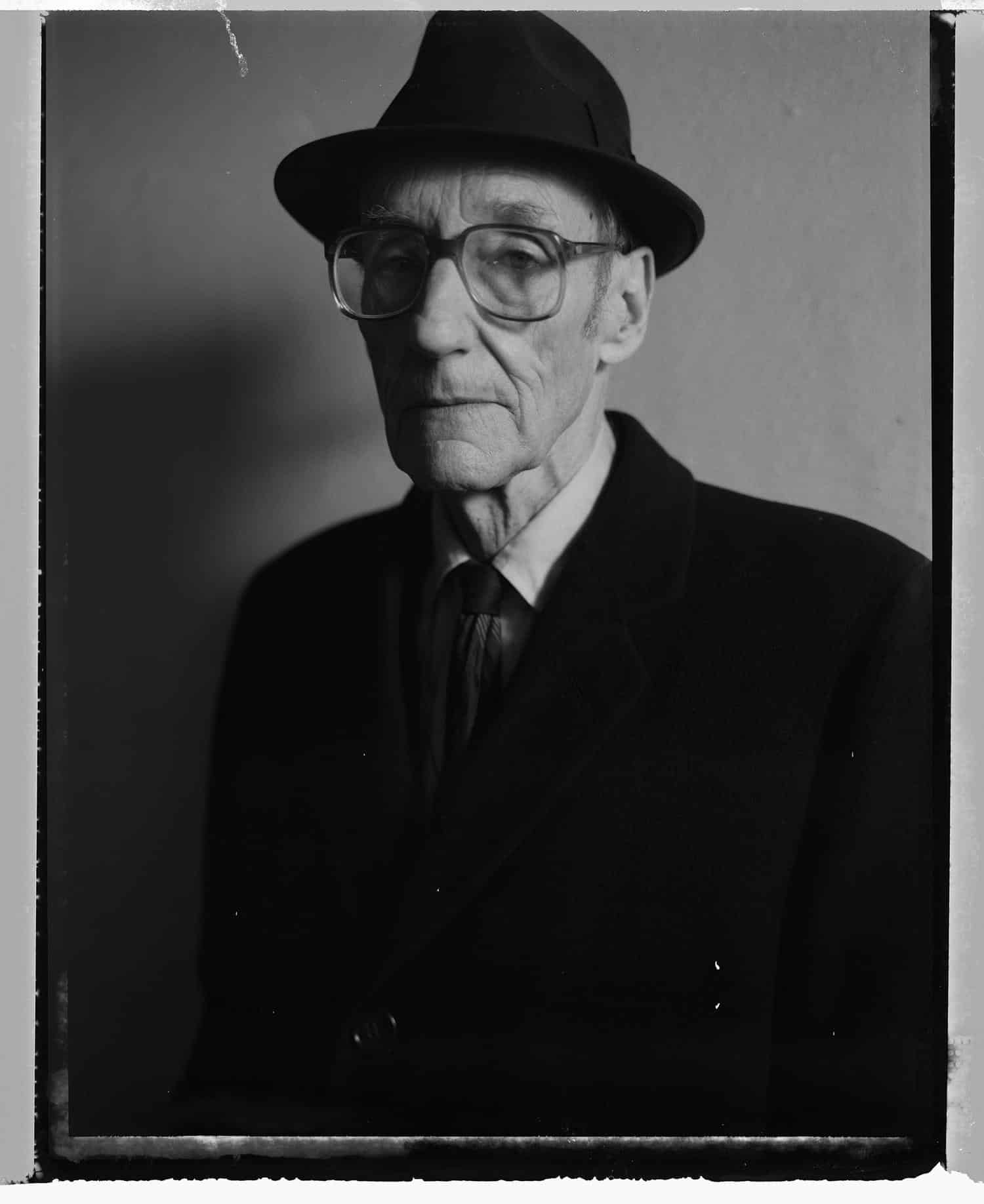

As Luca Guadagnino’s adaptation of William S. Burrough’s Queer arrives on our screens, we explore the writer’s own hallucinatory and disturbing cinematic compositions

In the introduction to his novella Queer (1985), William S. Burroughs sets down his reasons for writing this sequel to his earlier, at the time highly contentious work Junkie (1953), describing the follow-up as an outpouring of self:

“While it was I who wrote Junky, I feel that I was being written in Queer. I was also taking pains to ensure further writing, so as to set the record straight: writing as inoculation. As soon as something is written, it loses the power of surprise, just as a virus loses its advantage when a weakened virus has created alerted antibodies. So I achieved some immunity from further perilous ventures along these lines by writing my experience down.”

Much of Burroughs’ work is concerned with a desire to shield oneself from malevolent exterior forces. For Burroughs, writing—as well as other art forms—possessed an almost shamanic capacity to ward off unwanted “ugly spirits” that would tamper with the mind. Together with Brion Gysin, a fellow experimental writer and artist, he conceived of the “cut up” technique, a way of stitching together various materials in a montage-like form in order to disrupt the hypnotic flow of language and unveil hidden meanings, thereby overcoming a system of control. The idea of severance permeated Burroughs’ self-mythology. The writer snipped off the end of his pinkie finger while in a particularly tumultuous relationship in the 1940s.

Although the Beat generation author is best known for his 18 novels and novellas, the cinematic realm offered a crucial extension of his core artistic philosophy. Burroughs’ contributions to avant-garde film, while as boundary-pushing, versatile and transgressive as his writing, have gone relatively unacknowledged. According to Gysin, even the author’s literary work was visual, saying of the process behind Naked Lunch (1959): “Burroughs was more intent on Scotch-taping his photos together into one great continuum on the wall where scenes faded and slipped into one another, than occupied with editing the manuscript.” As the third feature-length Burroughs adaptation, Luca Guadagnino’s Queer, arrives onscreen, it is impossible to overlook how enmeshed film was with the fashioning of Burroughs’ public persona as a countercultural icon, as well as his artistry.

From the 1960s onwards, Burroughs embarked on a series of collaborations with Anthony Balch, an exploitation movie director who Burroughs met at the famed Beat Hotel in Paris. Their films, in which both frequently starred, continued the projects started by Burroughs’ writings, probing questions of queerness, identity, life on the margins, oppression and the ominous world to come. Less ubiquitous than the cut-up technique, the author’s “playback technique”, whereby audio is recorded at a certain place before being played back there at a later date (apparently allowing Burroughs to lay curses on venues he disliked such as London’s Moka Coffee Bar), consolidated his standing as part in the “chaos magic” movement and variations on this process were woven into his films. In Balch and Burroughs’ first short Towers, Open Fire (1963), Burrough’s voiceover (reading from the “Where you belong” section of The Soft Machine (1961)) is spliced together with brisk snippets of shadowy, obscure footage. “You’re only human cattle,” Burroughs chants, as the camera glides over tribal masks, headlines announcing the stock market crash and finally an off-kilter smattering of apocalyptic imagery. In its heavy, quick-fire editing and phantasmagorical visuals, there is something trance-inducing.

Daniel Craig in Luca Guadagnino’s Queer (2024)

Daniel Craig and Drew Starkey in Luca Guadagnino’s Queer (2024)

Burroughs’ cinematic compositions are hallucinatory and disturbing. As he writes in The Place of Dead Roads (1983), “You don’t sell a film by saying you won’t show it. There may be secrets too horrible for a man to know and keep his own sanity but that won’t go down in Hollywood, Mister.” This darkness stems from an obvious place: the influence of drugs and addiction on Burroughs’ oeuvre is unavoidable, in The Cut Ups (1966)—a 20-minute short film light on plot but heavy on foreboding atmosphere—manifesting as a preoccupation with medical imagery and dizzying, dreamlike shots of spinning lights.

Along with the films Burroughs helmed, the author’s countless appearances in other filmmakers’ work helped to grow his enigmatic onscreen presence. Cameoing in everything from Gus van Sant’s Drugstore Cowboy (1989) to the New York documentary Underground & Emigrants (1976), Burroughs seemed to have a hand in all adaptations made of his work. Burroughs himself is the framing device in the Francis Ford Coppola-produced short The Junky’s Christmas (1993), a wry spin on Christmas tales of charity and goodwill. In Decoder (1984), a neon-soaked, Cold War era cyberpunk movie from German director Muscha, loosely based on Burroughs’ work, the author himself features twice, explaining his conviction of reading “between the lines”. The film sees a young man uncover a conspiracy among burger chains to use illegal soundwaves to control customers. Perhaps the adaptation in which Burroughs had the least control—though still observing from the sidelines—was David Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch (1991), a version of the tale which, adopting Burroughs’ own magpie-like sensibility, liberally blended the novel’s plot points with biographical elements.

“I’m not queer. I’m just disembodied,” is the recurring refrain in Guadagnino’s Queer—a phrase found just once in the book. The director takes a similarly laissez-faire approach to adapting Burroughs, injecting biographical details into the narrative and peppering the film with fantastical, surrealist sequences reminiscent of Naked Lunch. Queer is the first adaptation of his work in which Burroughs, inevitably, could not be involved. The novella, as his introduction indicates, is also one of his most personal works. Yet Guadagnino, while staying faithful to his own style, poignantly captures Burroughs’ knotty relationship with queerness. In borrowing images from throughout Burroughs’ life and work and disjointedly connecting them together, Guadagnino deftly captures the Beatnik’s own fractured, fraught and lonely perception of identity.