The Chilean-Palestinian singer, fresh from her acclaimed tour, discusses freedom on stage, writing music with her mother, and growing her own sonic universe.

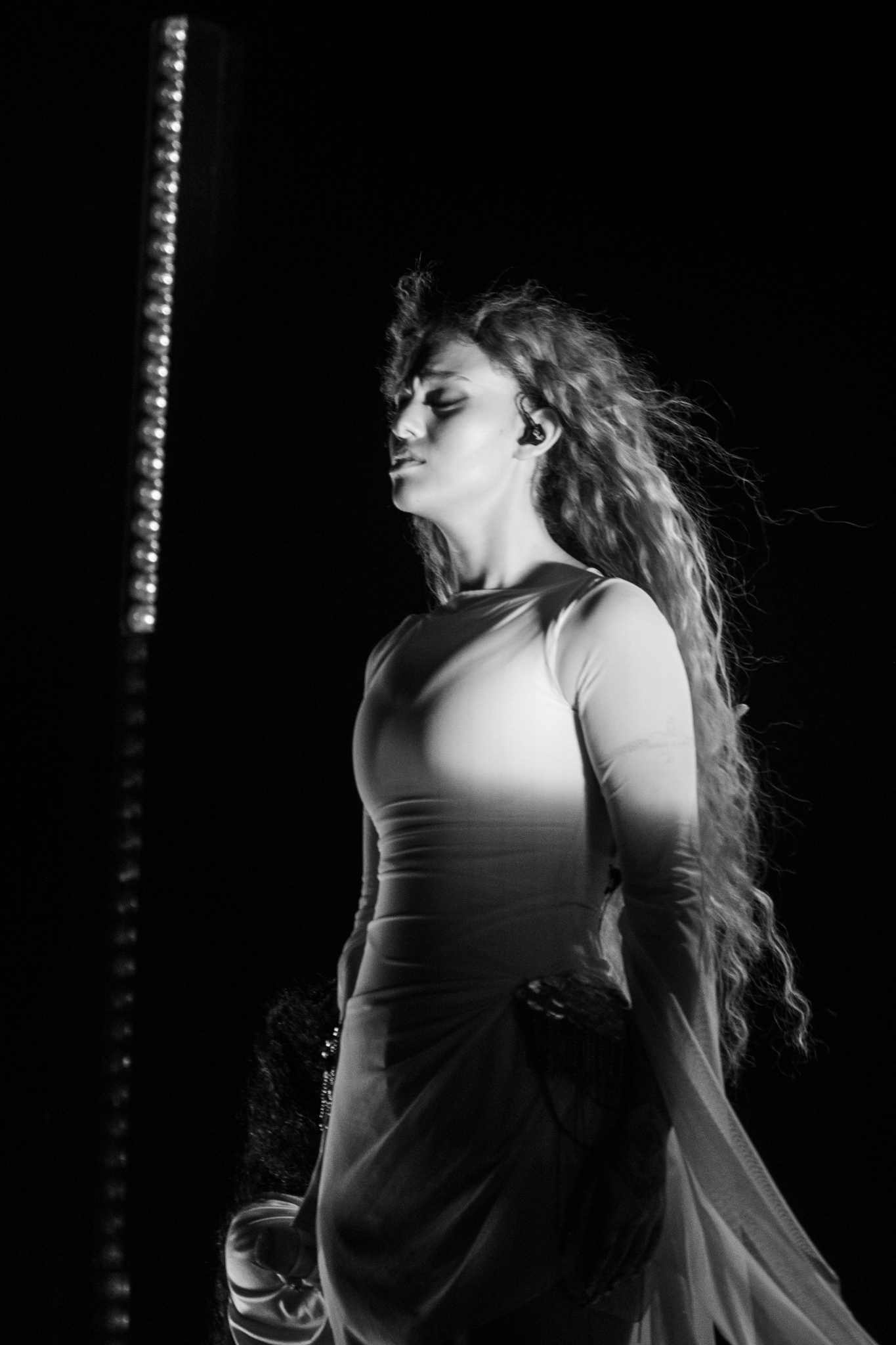

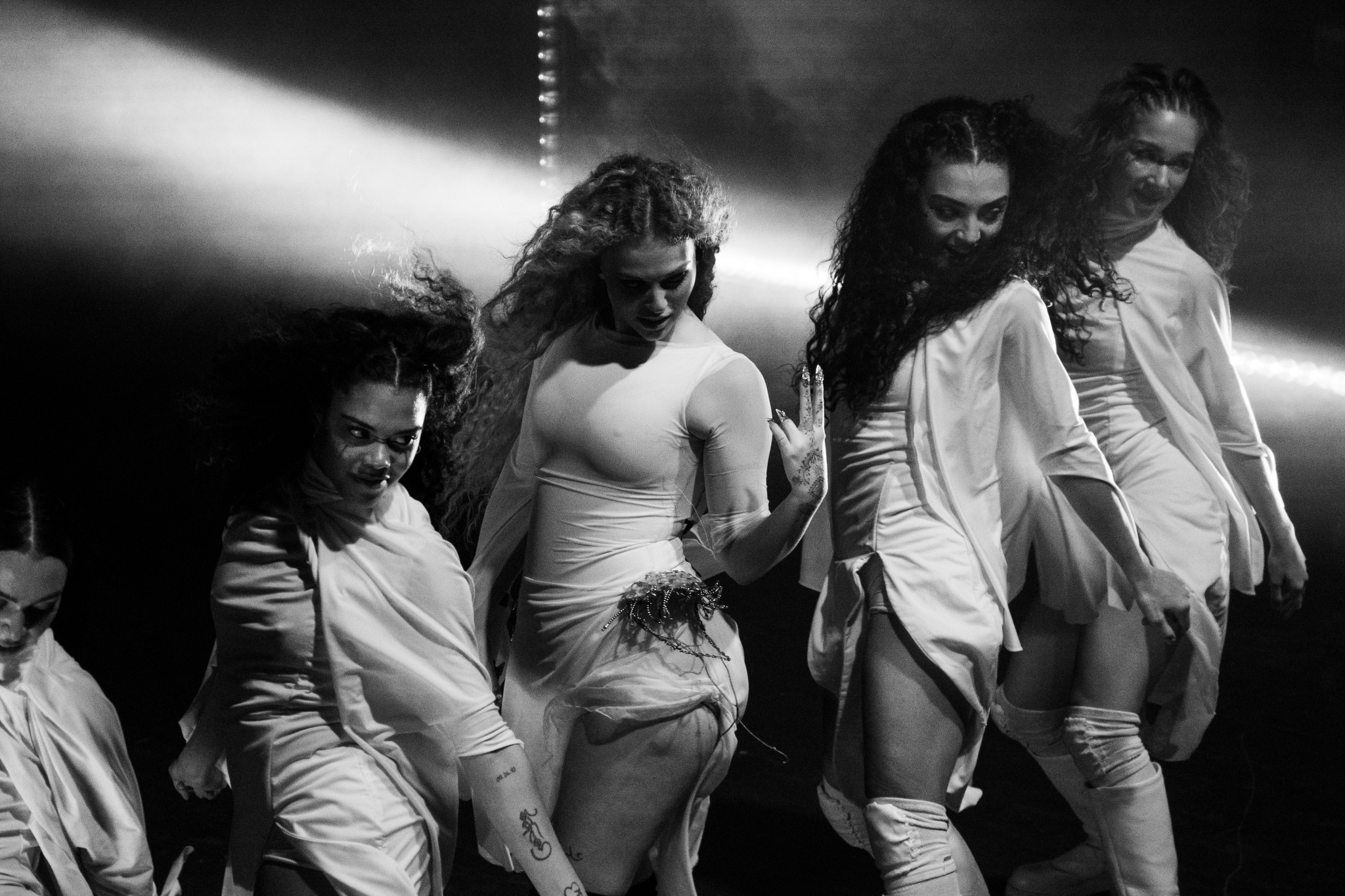

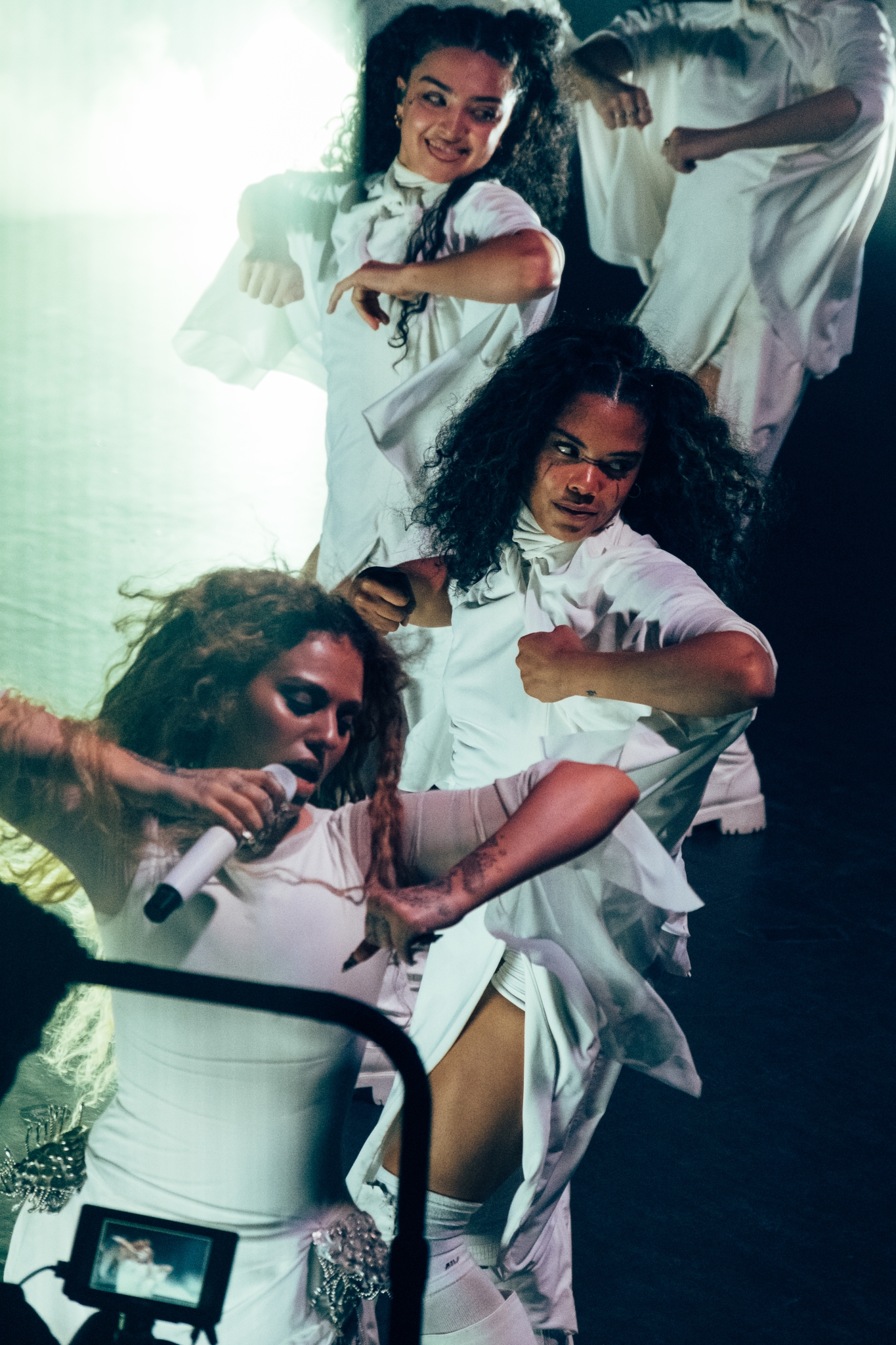

The site manager at Shepherd’s Bush Empire in West London is wearing a terrifying scowl. He’s just been given the news that Elyanna is driving her tour bus around to the front of the venue to surprise hundreds of fans waiting at the barricades. It’s a safety hazard in more ways than one, he insists, but despite the steam coming out of his ears, the Nazareth-born artist’s act of rebelliousness brings, not injury, but an authentic moment of community to the tail end of her London show. As she emerges from the roof of the car, a joyful grin on her face, the crowd rejoices: dancing, singing, laughing in unity. Many among the sea of fans are proudly wearing the keffiyeh, a black-and-white headscarf that has become a symbol for Palestinian liberty. A young girl, no older than six or seven, stands giddily with her father, her long blonde hair curled, mascara thick: a tiny doppelganger of the idol now standing before her. “She’s a little superstar,” Elyanna exclaims over Zoom a few days later, transformed from the black-booted, porcelain-white-gowned diva I saw on stage into a regular 22-year-old, hair loosely tied and dressed for comfort in a baggy sweatshirt. “As an artist it’s fulfilling seeing my fans really commit to the universe that we’re creating,” she continues. “When I see young fans of mine embracing their curls, embracing their style and culture at such a young age, it makes me feel like I’m taking the right path—fulfilling something that’s bigger than me.”

London was the last stop on Elyanna’s continent-spanning world tour, a celebration of her acclaimed, genre-bending debut album Woledto [loosely meaning rebirth], but she’s taking some time out to spend the holidays with her family in Los Angeles, where they emigrated when the singer was 15. However, she makes it clear that the work hasn’t been put to sleep just yet. “It’s very hard for Elyanna to rest,” she jokes. “Me and my brother are always on the run.”

Elyanna and the brother in question, Feras—musician, producer, and the other brain behind her music—are in prep mode, gearing up to spend a few nights on tour with Coldplay in early 2025. Back in June 2024, the British rock band invited Elyanna, along with Little Simz, to the Glastonbury stage to perform their collaborative single ‘We Pray’ (also featuring Burna Boy and TINI). A few months earlier, she had become the first artist to perform a full set in Arabic on the Coachella stage. It marked her biggest solo performance yet—a far cry from humble beginnings spent honing her craft, covering classic Arabic ballads by the likes of Abdel Halim Hafez and Nancy Ajram on YouTube (as well as the occasional Adele and Rihanna song).

But make no mistake, the depths of Elyanna’s musicianship reaches far beyond global stages, late-night TV appearances, and a co-sign from one of the biggest bands in the world—it runs through her blood. Hailing from a family of Palestinian poets, it’s no surprise that Elyanna’s debut is filled with lyrical and sonic odes to her roots, drawing on both her Arabic and Chilean heritage to create whirling grooves of infectious Latin-infused Arab Pop. Standouts include ‘Mama Eh’—a gorgeously tribal stage anthem—‘Callin’ U (Tamally Maak)’—a spiritual bop that ingeniously breathes new life into Amr Diab’s smash hit ‘Tamally Maak’ by re-folding it into a prior interpolation of the song by Danish hip-hop group Outlandish (‘Callin’ U’)—and ‘Sad in Pali’, which sees the artist sample a live recording of her grandfather performing poetry at a Palestinian wedding for a stirring tribute to home. The songs on Woledto make up a universe of sounds, a free-flowing artist masterclass on how to break the doors down and announce yourself to the world. But, as Elyanna tells me, building a universe is just the beginning.

Luke Georgiades: I wonder if you feel like you embody a different persona when you get on stage and perform?

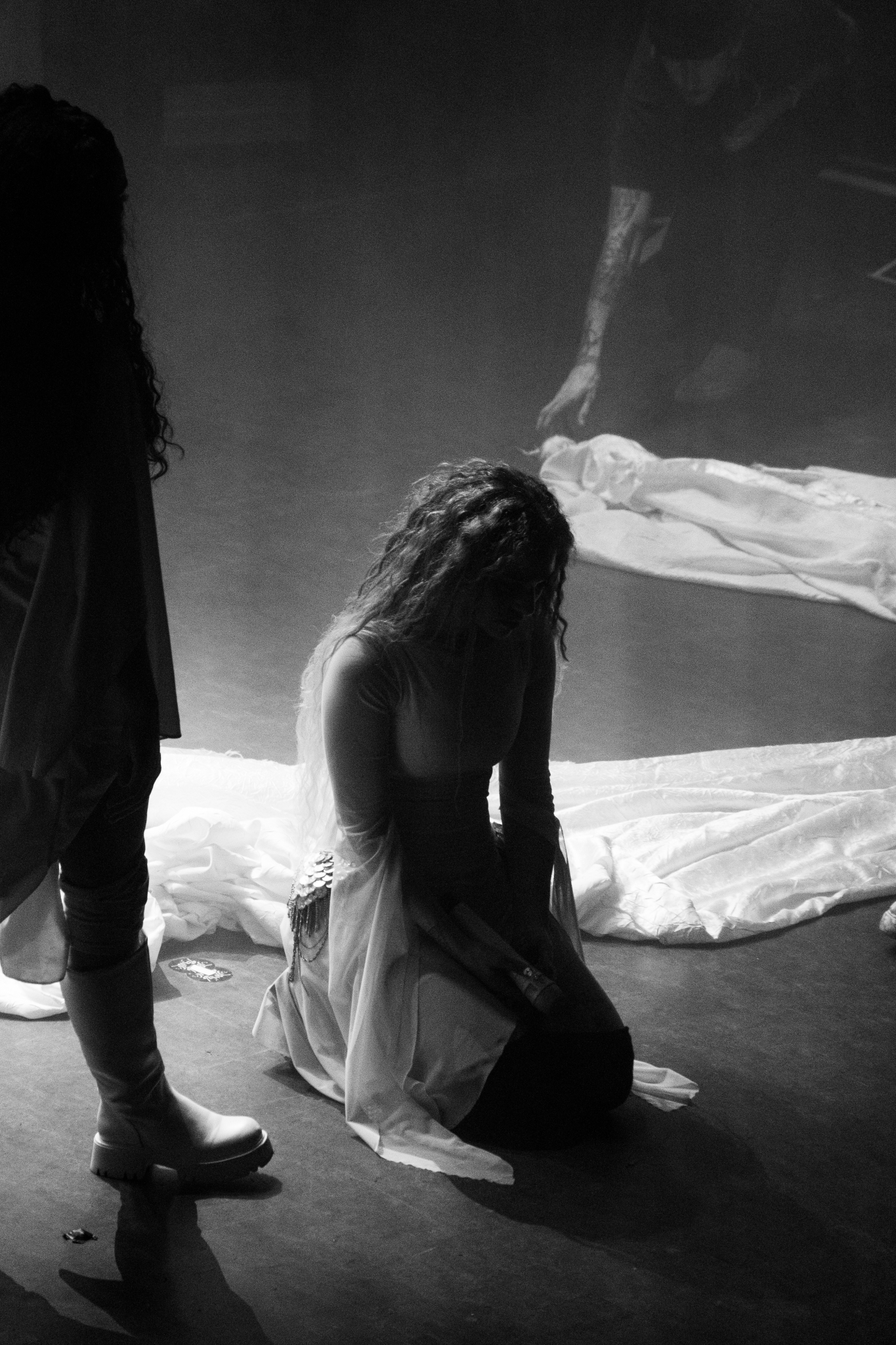

Elyanna: I’m different when I go on stage. I feel like whatever I do there, I’m excused… Because it’s not really me. It’s me hiding under a persona, which I find fun, because that persona shouldn’t exist off stage. That persona shouldn’t talk to people in real life [laughs]. She’s intimidating. The perfect time to be that person is when I’m free, that’s when I feel like I can represent my art through her. The show, even the order of the songs, is about woledto: It’s the rebirth, it’s about duality, and bi-polar emotions. That represents a lot of people. Sometimes we feel crazy, and sometimes we feel soft—I wanted that attitude to flow through my persona on stage.

LG: Your grandfather was a Zajal poet and your mother is also a poet. How have they influenced your artistry?

E: With this album I wanted to draw from my own history. A lot of the lyrical content is ancient—they’re phrases that have existed for years in poetry back home that we wanted to melodise and put into songs. A lot of songs I sang in my accent and other songs I sang in fusha [classical Arabic], It was both urban and it drew on the old Egyptian dialect. I don’t want to forget my age, and my slang, and the way I express words. There’s no rules. It was a unique experience to write songs with my mom and brother, to sample my grandfather’s poetry. I’m honest when it comes to my lyrics. Whatever I say, it’s really what I think. I’m saying it because I truly believe in it. I want to sing it like I mean it.

LG: Was writing with your mother a different experience to writing music with other songwriters?

E: I have a close relationship with my family. We’re open with each other. If I want to say something, they’ll take that step with me. My mother always taught me to be rebellious, like she is. So if I tell them I want an idea, I don’t have to tell them why I want it, they’ll accept and support it. We’ve built a nice flow together, and because of that we’re able to write a song like Olive Branch, which is a song for my hometown. It’s a prayer. It’s a lullaby. Me, my brother, and my mother were born and raised in Palestine. Who could speak on it better than those who were there? I try not to cry when I sing that song, but seeing how people react to it during the show makes me very emotional.

LG: Why did you want to close the album with that excerpt of your grandfather reciting his poetry?

E: It’s from a video I have of my grandfather at a wedding, where he was doing dizishal, which is a poetic freestyle in which you go back to back with another person. He was an amazing poet. I got my talent from him. So I wanted to pay tribute to him in a big way, like theatre, with violins, and deep, dramatic words. He’s the only feature on my album. My album title means I Am Born—how could I not end it with a tribute to my roots?

LG: In a video teaser for Woledto, you said, “I planted who I am next to an olive tree, to blossom into a white flower”. What does the imagery of an olive tree mean to you?

E: Back home in Nazareth we had an olive tree outside our house. It’s a symbol of Palestine—of home. For us Palestinians, the olive branch represents hope, but more than anything it’s a reminder that we should never forget our identity. Even here, as an immigrant in America, I had to fight to be heard as an Arab artist. There are a lot of people here who can relate to that, who aren’t necessarily artists but never had an artist that spoke to home like I do. A lot of people don’t even understand what I’m singing about, but they’re there because they feel connected or because they want to learn. I feel like everybody was lost, they were looking for community, and now we’ve finally found each other. I want to expand that now, make it bigger and better. I don’t want it to ever stop growing. It’s time. We’ve been doing this for a long time, and there’s too much beauty in our culture for it to be contained any longer.

LG: Is it the fusion of multiple genres that has made international audiences so receptive to Arabic music?

E: All of us stand on the shoulders of the Arab artists who came before us. That’s why we are here. I started doing this when I was 15 years old. I made Ana Lahale, and I was here in LA, and there were a lot of people who didn’t understand the art I was trying to make. They didn’t think it was cool. Seeing where I am now, and seeing that there are others standing with me… it takes an army. I was lonely when I was 15. I was always looking for other young Arab artists and it made no sense to me when I couldn’t find them. But now, starting this and watching people hop on the wave is exciting. We need this to go where we want to go. When I create, I never think about whether what I’ll be doing will be different. It’s different because I’m different. I am born in the Holy Land. I was inspired by it. I was inspired by LA when I moved here. I was inspired by the world. There’s no explanation for things like that. This comes from the skies. Chris Martin always says that to me, “It comes from the skies.” I feel the same way. It just comes to you, and you don’t know why, and from where. I don’t know how I became so blessed with such a talented brother and sister, and such a supportive family. It was meant to happen. It’s something from the skies.

LG: You’ve mentioned that you made this album with freedom in mind, rather than perfection. What do you mean by that?

E: I wanted to make something raw. When I made my first two EPs I was still discovering my sound. What do I want to represent? A lot of people tried to direct what I should be doing. They wanted to Americanise me. But once I ignored all the noise, it started to click. Me and my brother sat in our living room, on the piano, and he started playing and I started singing melodies… That’s the rawest thing I’ve ever done. I usually hate comfort zones, but being at my home studio was a necessary comfort. An artist with no message loses you. It needs a purpose, and I’ve finally found my purpose. My music needs to feel like home. The mawal, the spiritual vocals, the chants, the visuals, the synth, the drums. All these details that created a universe—that created an original in me. Woledto was the seed, but I’ll tell you this now: my universe is here, it’s going to keep growing, and everybody is welcome to live inside it.