She wrote over 500 pieces for The New Yorker. Only one caused controversy. Author Elisabeth Robinson finds out why the pioneer of the celebrity profile was accused of taking down Hemingway—and who might have actually been behind it.

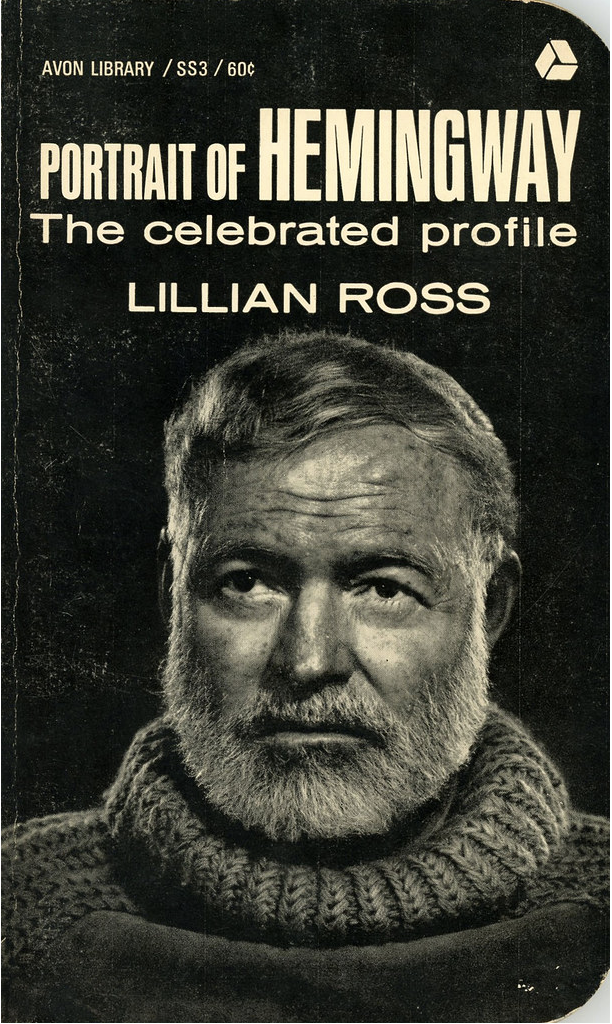

Seventy-five years ago, a young reporter wrote a magazine profile of Ernest Hemingway that is still admired, reviled, and studied today. Her reputation was made on it and his was stained by it. The New Yorker profile caused a furor and I wondered why.

The portrait Lillian Ross drew was new in both style and substance. With short declarative sentences and a stripped-down narrative, like Hemingway’s style, the piece led some readers to believe it must be a parody. Key details created the illusion of reality, and well-placed omissions asked the reader to infer the story’s meaning. In 1950, a ‘fact piece’ had not been written this way, this brilliantly.

Neither had the banal and tawdry details of a celebrity’s life been revealed on such highbrow pages. As one Vanity Fair writer told me, “You can draw a straight line from Lillian Ross to TMZ.” The Hemingway portrait became known as the first ‘warts and all’ profile, written as if by a ‘fly on the wall’.

You should read it and see what you make of it. The first time I did something bugged me about it. The dialogue sounded dubbed; Hemingway’s unrelated opinions felt jammed together; something was out of sync. The physical details were fussy; I wasn’t interested in the style of the hotel furniture or what colour belt he needed to buy. He was putting on a show, with hammy gestures, “Injun-Talk”, and punctuating his well-worn jokes with the verbal bow, “How do you like it now, gentlemen?” (which became the profile’s title). I had an idea of Hemingway, and this wasn’t it.

Many readers shared my feeling. The New Yorker and Ross were attacked for what was seen as a hatchet job on an American legend. The Times called it “a disgusting intrusion into Hemingway’s private life… and a new low for the magazine”.

Had her pages been downcycled to ‘fishwrap’, this mid-century lit-shitstorm would have burned out long ago, but in 1961, shortly after Hemingway’s suicide, Ross published it as a book. Besides royalties, the book gave her the chance, in the foreword and jacket copy, to correct her critics: the portrait was “affectionate”, she wrote with undisguised irritation, and for evidence she added that Hemingway “approved” it. Rather than settle the scandal, fresh mud was slung—one prominent critic called Ross “a journalistic Delilah”.

Twenty-eight years later—(28!)—for the 100th anniversary of Hemingway’s birth, Ross doubled-down in an afterword, using her “friendship” with Hemingway to defend the profile as “affectionate”. 16 years later still, The New Yorker’s editor-in-chief, David Remnick, in his introduction to Ross’s collection, Reporting Always (2015), said that both The New Yorker and Hemingway were “astonished” that anyone could consider the profile damaging; even the New York Times Book Review toed the party line that “Hemingway loved the piece”.

He didn’t.

And Ross knew it. She knew it in 1950. Ross’s own friends told her as much: Norman Mailer called Hemingway a hypocrite for pretending to be friends with Ross after the portrait, and J.D. Salinger told her the piece was “merciless” and “sad”.

When Ross’s New Yorker colleague Wolcott Gibbs took heat for a scathing review he replied with this stock letter: “Dear Sir, You may be right. Sincerely, Wolcott Gibbs.” Instead, any chance she got—and some she made—Ross insisted that the portrait was “affectionate”.

I called up The New Yorker’s former editor Charles McGrath for some background. “We at The New Yorker were told (and I grew up believing) the profile was a kind and affectionate piece. It wasn’t. But it was scathingly brilliant. It exposed celebrity and very slyly gets at it, without comment, with only observations.”

There’s that word ‘affectionate’ again, like an ad slogan. In her seven-decade career, writing over 420 Talk of the Town pieces and some 80 others, including dozens of celebrity profiles from John Huston to Wes Anderson, nothing Ross ever wrote stirred up such sustained controversy— or required a marketing campaign. Why did this matter so much to her—and to The New Yorker? Who was this rookie reporter, and what was going on behind the scenes, in her life and in Hemingway’s, when the piece was made?

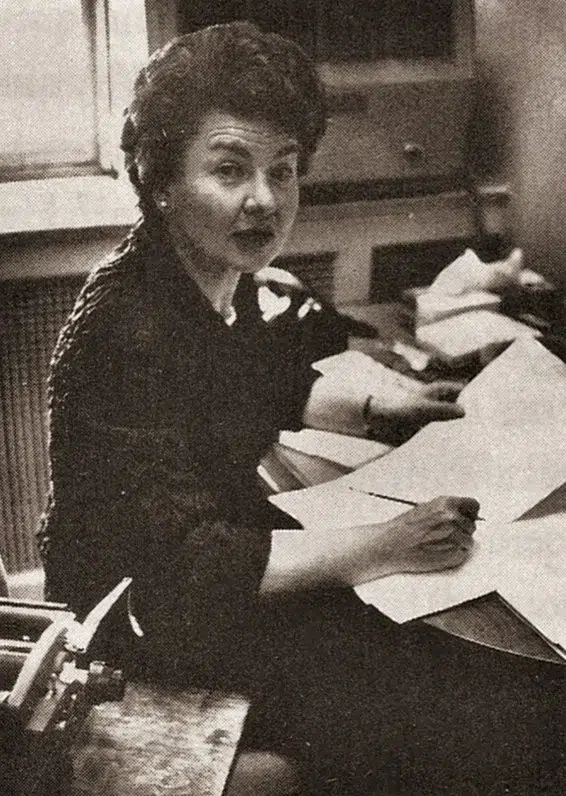

Born in upstate New York in 1918, Ross was the youngest of three children of Edna and Louis Rosovsky. Her father was a Russian socialist who escaped Siberian prison—twice—only to find himself in Syracuse, New York, surrounded by Republicans. He painted cars. In her memoir Here But Not Here (1998), Ross recalls delivering Collier’s Weekly door-to-door, admiring the “luxurious” homes, becoming “infatuated” with glossy magazines, and falling in love with the movies. She went several times a week—alone; yet she was “quietly satisfied to observe the restless antics of the other children around me.” Not long after the family moved to Brooklyn, in 1931, her mother, a frustrated poet-housewife, died.

“I didn’t have much in the way of adolescent objections to myself,” she wrote. “I had a round face and extremely curly hair and I kept those features more or less all the way up the line. It was a useful look that seemed to go with being a listener not a talker.”

After a short stint at PM magazine, Ross was hired by The New Yorker, one of three women to fill in for men off fighting in WWII. Her work was uncredited and ‘masculinised’ to make it sound like it was written by a man. After three years of writing short Talk of the Town pieces (for less pay than her male counterparts) Ross wanted a big story and a byline.

On 8th June 1947, the editor-in-chief, Bill Shawn, learning it was Ross’s birthday, invited her up to his place on East 96th Street for some cake. “Bill’s wife Cecille made a big effort to make the occasion seem natural,” Ross wrote “but the atmosphere was one of tension and nervousness.” Ross ran.

First to Mexico, to report on a Brooklyn-born bullfighter, then to Hollywood, where Senator Joe McCarthy’s House Committee was hunting communists. Ross must have been awestruck to meet her celluloid heroes, John Huston, Humphrey Bogart, and Charlie Chaplin—and then to be liked by them, too (Ross would later write about Chaplin and Huston). But there isn’t a trace of fangirl in her brilliant satirical story Come In, Lassie! (1948). The actors talked about their blacklist anxieties and Ross was listening. No one ever questioned her quotes; if one did there would be no evidence, as Ross relied only on her own short-hand on 3×5 notecards.

In no hurry to return to the office, Ross next caught a train to Idaho and dropped in—on Christmas Eve—on Ernest Hemingway. She wanted to talk to him for her matador story. Hemingway, a former reporter himself, invited her into his small, rented tourist cabin where two of his sons and his third wife Mary were eating breakfast. Ross and Hemingway hit it off and began corresponding about bullfighting, baseball, and books. In his first letter to her, Hemingway was eerily prescient: “Never believe anything you read about Mr. Papa,” he cautioned. “It is all scheiss. I never aided it but I may have abetted it by not coming out and formally denying crap.”

In late 1949, after a 10-year struggle, America’s great novelist had finally finished his “big war book”. Ross asked for an interview. Hemingway loathed them—vivisections, he called them—but he could use some good publicity to prime the critics and the public for his new book. And Ross clearly liked him. He could trust her. He told her to meet his plane in New York on 16 November.

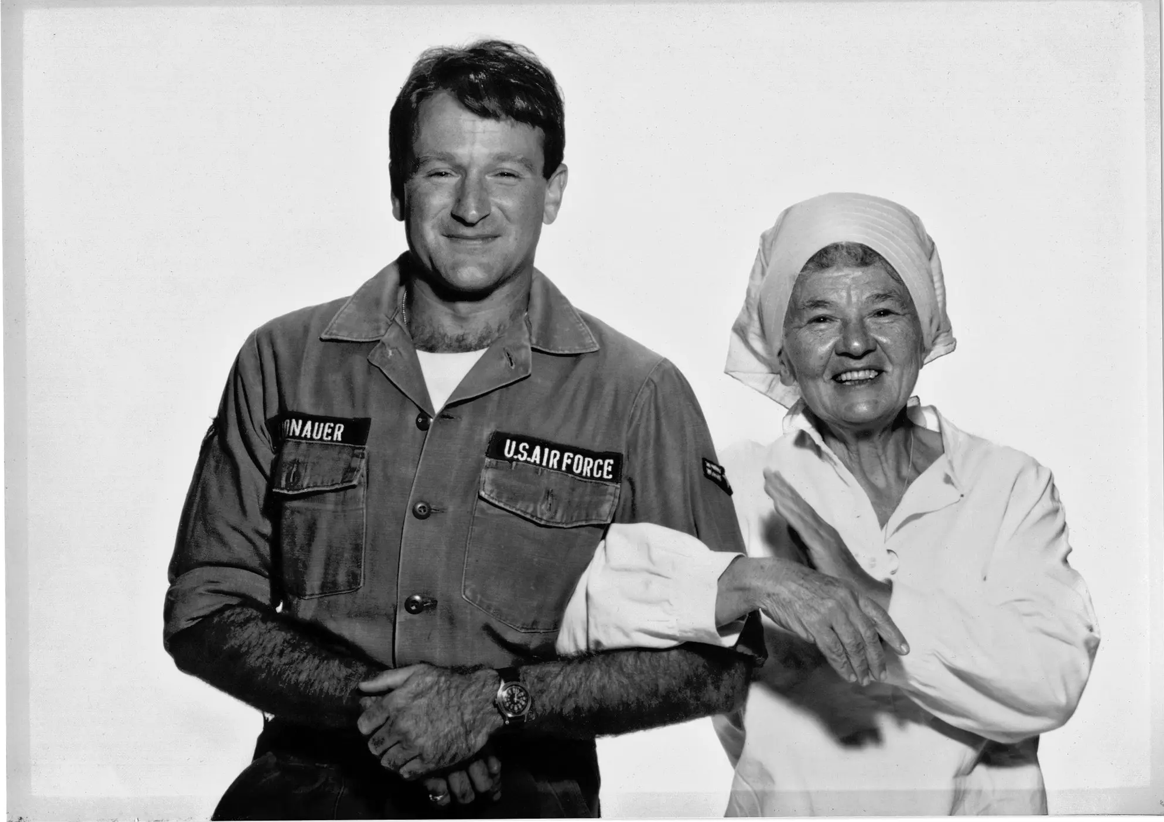

Robin Williams and Lillian Ross, shortly after the release of Good Morning, Vietnam (1987).

“Anyone who trusts you is giving you a form of friendship,” Ross wrote in her introduction to Reporting Back (2002). If you spend weeks or months with someone, not only taking his time and energy but entering into his life, you naturally become his friend. A friend is not to be used and abandoned.”

At the airport, clutching his new manuscript, Across the River and Into the Trees (1950), to his chest, Hemingway told Ross, “She’s better than ‘Farewell’,” referring to his last bestseller, A Farewell to Arms (1929). “I think this is the best one, but you are always prejudiced, I guess. Especially if you want to be champion.” Four double bourbons later, they took a taxi to Manhattan. At the Sherry-Netherland hotel, he enjoyed champagne and caviar with his wife Mary and Marlene Dietrich, who dropped in from the Plaza. The next day Ross and Papa went shopping for a coat, to the Met Museum with Mary and son, then returned to his suite to meet his editor for another wine-soaked lunch.

Or at least that’s how the story goes in The New Yorker profile. In truth, many friends were at the airport and hotel—Ross even brought her sister along; there was a party going on all weekend. Four months later, when the Hemingways returned from Europe, the party resumed.

One night, dining with friends at the celebrity restaurant 21, the bestselling novelist Irwin Shaw, an old friend of Mary’s, stopped by to say hello. Hemingway (offended by Shaw’s fictionalisation of him and his brother) exploded, his insults silencing the room. Sitting at his table, observing Papa’s drunken tantrum, was The New Yorker’s publisher Harold Ross (no relation). The rough-hewn, Colorado-born publisher enjoyed sending up the rich and famous; his magazine had begun as a humour magazine. How did Hemingway’s tantrum and the parties, which he also attended, influence the publisher’s notes on the portrait? His typed questions and comments often ran longer than a writer’s work.

The New Yorker archive at the New York Public Library contains rooms of thousands of pages and hundreds of New Yorker stories… but not the original manuscript of one of its most famous stories. Nor are there any editorial notes. Harvard’s Houghton library holds Ross’s papers. The only draft of the Hemingway profile is the last one she used, in the 1999 book reissue. The one controversial story in Ross’s career… and the editorial notes and manuscript are not available.

Lillian Ross, Reporting Always: Writings from The New Yorker

Small, bald, slope-shouldered, soft- spoken Shawn was a revered, genius editor, who published historic pieces like John Hersey’s Hiroshima (1946), Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), and Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1966). Ross had been writing for him for five years. “Bill [Shawn] and I were both lightheaded with laughter and happiness over [the profile],” Ross wrote. It was Shawn’s idea to limit the story to two days, and to only what Ross observed and heard.

I suppose collapsing the time doesn’t change its nature, but omitting there was a party going on does. Those oddly jammed-together opinions and well-worn jokes? Hemingway was regaling old friends at his party. The ‘invisible and observant’ Ross was lurking around the suite grabbing juicy quotes out of the revelry like silvery salmon from a stream. And then she and Shawn cut and pasted them to make a composite of the man.

Lillian may not have been laughing at Hemingway and Marlene Dietrich, but I bet Harold Ross and Shawn were, like the “gleeful parole officers” one critic called them. Shawn was as different as a man could be from Ernest Hemingway. Was the teetotaler, multi-phobic, impeccably mannered editor the one counting Hemingway’s drinks? Was it Ross, not her readers, who just didn’t get what they had made together? It wouldn’t have been the first time she was baffled by the response to her work. Laughing at one of her earliest Talk pieces about the conservative women’s group the Junior League, Gibbs remarked, “You really handed it to those bores!” Ross was annoyed; that wasn’t it at all— she liked those gals. Just like she liked Hemingway.

Lillian wrote that Shawn’s joy at the Hemingway profile “meant more than any praise” she received later. One former New Yorker editor snarkily observed, “Bill Shawn and Lillian Ross together made one brilliant writer.” Was Shawn one reason Ross was so defensive?

On 13th May 1950, the profile hit the stands. Shawn invited Ross for the first time to lunch at The Algonquin. “It’s a wonderful piece, darling,” he told her, blushing. “It’s going to make journalistic history,” he went on, but Ross was too disturbed by the endearment to hear it. Soon after, handwritten love poems and messages began appearing on her desk. While working together on another piece, the editor-in-chief told her he was in love with her. He took to looking up at her apartment building at night and calling her from the payphone. Ross had feelings for him, too, but Shawn was married, with three young children— and, perhaps more than the man, Ross loved her job—there was no other magazine like The New Yorker. How could she keep it if she got involved with him? She was “in turmoil”. Ross ran again. This time, to Hollywood.

Meanwhile, down in humid Havana… Hemingway had read the profile “with horror”, according to his friend, A. E. Hotchner, who was at the airport and the parties, too. ‘Hotch’ claimed Hemingway didn’t receive the proofs in time to stop the story (the dates of Ross’s and Hemingway’s letters back that up). Friends called, furious on his behalf. Dietrich, angry at her portrayal, felt betrayed and ended their friendship (they eventually made up). Papa started firing off letters. Here are a few:

1st May: To his publisher he said that the piece would “make me plenty new good enemies.”

11th May: To Ross, that “he didn’t like being a character in the piece but planned to straighten up now and will fly right. Will speak a language that will put Henrietta James to shame and will confound all ticket holders with my erudition.”

23rd May: To Dietrich: “I hope I didn’t talk that way and didn’t act like such a conceited son of a bitch.”

25th May: He worried: “How could readers take this ‘Choctaw-bumbling punch-drunk wreck’ seriously?”

The number of reassuring letters he wrote to Ross proves her regret and his magnanimity. Eventually he admitted to her that the “good old profile made me about as many enemies as we have in North Korea…”

Eleven years later, when Hemingway committed suicide, Ross rushed out the portrait as a book and in her foreword demonstrates a surprising lack of acuity by including, in her defence, a letter Hemingway wrote to her. “All are very astonished,” he wrote, “because I don’t hold anything against you who made an effort to destroy me and nearly did, they say. I always tell them how can I be destroyed by a woman when she is a friend of mine and we have never even been to bed and no money has changed hands?”

A woman’s words couldn’t destroy him, only her body or greed could. Papa was magnanimous and sexist. He nearly took off Shaw’s head for a fictionalised version of him; Ross was a woman, a friend who sent him caviar and shirts for years. To an aspiring biographer, Hemingway wrote: “After The New Yorker piece I decided that I would never give another interview to anyone on any subject… If you say nothing it is difficult for someone to get it wrong.”

Hemingway lived by the sword and died by the sword, but that didn’t mean, as Ross and The New Yorker insisted for 75 years, that he didn’t… bleed.

“Anyone who trusts you is giving you a form of friendship,” Ross wrote in her introduction to Reporting Back (2002). If you spend weeks or months with someone, not only taking his time and energy but entering into his life, you naturally become his friend. A friend is not to be used and abandoned.”

“Anyone who trusts you is giving you a form of friendship,” Ross wrote in her introduction to Reporting Back (2002). If you spend weeks or months with someone, not only taking his time and energy but entering into his life, you naturally become his friend. A friend is not to be used and abandoned.”

Elisabeth Robinson

Across the River and Into the Trees was savaged by critics and ignored by readers. His wife, Mary, finally fed up with his drinking and whoring, left him (she would come back months later). Hemingway went fishing in the Gulf one night and… jumped. He thought of his sons and surfaced. In the morning, he began writing a new book. It would be about an old and hungry fisherman and the great fish he would die trying to catch.

Two years later, The Old Man and The Sea (1952), Hemingway’s last novel, was published the same month a new writer’s first book was published to great acclaim. A true story written like a novel, wholly original in style and substance, Ross’s masterpiece, Picture (1952), exposed the hilarious, treacherous, and “sad reality” of glamorous Hollywood. In his New York Times review, Budd Schulberg wrote, “[Picture] is a book with many morals. Perhaps the first and most obvious is that, if you value your privacy, if you do not want to be caught with your clichés down or your pretensions showing, Miss Ross is not the lady to ask into your home.”

Ross had run to Los Angeles to get away from Shawn, but had grown closer to him through daily calls and letters. When she returned, “one day I was in my office… when Bill appeared. We looked at each other. It was late morning. Neither of us spoke. We went outside, got into a taxi, and still, without a word, went directly to the Plaza Hotel.”

For the next 42 years, Ross and Shawn loved each other, working together at The New Yorker, sharing most meals and raising her adopted son in their apartment on East 86th Street, 10 blocks south of the home he continued to share with his wife and children. While promoting her memoir, Ross was asked if she considered the impact the book, with all its intimate and sexual details, would have on Shawn’s wife, Cecille, and children. “That isn’t the way one thinks when one is a writer,” she replied. “You don’t think about what the impact is going to be on other people. You think about what you’re writing.”

About the Hemingway profile, Ross wanted to have the last word (and the word was “affectionate”). About her life with Shawn, she had the only word; neither Shawn nor his wife wrote about their experience. Her memoir is a portrait of the other great man in her life, Shawn, and, like the Hemingway piece, it earned her enemies.

“Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible,” Janet Malcolm wrote in The New Yorker in 1989. Ross was anything but stupid.

When she was 13, she saw her first words in print in the school newspaper, and experienced “an unforgettable rapture”. A few months later, she was struck by this stanza from Lord Byron’s 1819 satirical poem ‘Don Juan’:

But words are things, and a small drop of ink,

Falling like dew, upon a thought, produces

That which makes thousands, perhaps millions, think.

“I discovered I could do something with words that I could do with no other medium,” she recalled. “And what I was going to do for the rest of the century.” Ross went on to become a pioneer in literary journalism, credited both with writing the first non-fiction novel and celebrity magazine profile. But she seemed to refuse to accept Byron’s warning that her words had consequences.

Wes Anderson, in his blurb for Ross’s book Reporting Always, said she gave us “the chance to sneak into the private worlds of the great and the fascinating (Chaplin, Hemingway, Truffaut, Huston).” She wrote about the Beats and The Beatles; Fellini, Scorsese, Eastwood and Anderson; John McEnroe, Ralph Kiner, Willie Mays, and a very peculiar matador, plus Mailer, Pacino, and Robin Williams—and many other portraits of the marvelous lives of others.

Besides going to the movies, as a child Ross loved putting pennies on the railroad tracks with her brother and sister. “[We] would watch as the trains ran over the pennies. We would stare at the glamorous passengers looking at us through the windows. Then we would collect the flattened, misshapen, marvelously ruined pennies.”

Main image: Lillian Ross, Ernest Hemingway and his sons, Gregory and Patrick. Ketchum, Idaho, 1947. By Mary Hemingway.