Once a transatlantic outsider, American writer JP Donleavy became Ireland’s most reluctant insider—a wealthy exile who romanticised a country that never quite welcomed him. From The Ginger Man to lawsuits and literary feuds, his legacy is as wild and contradictory as the land he wandered, mocked, and ultimately called home, learns Sam Murphy.

Centuries ago, ’travellers’ were little more than the homeless Irish who were forced to wander as handymen to survive hardship. Now they have become a perennially cursed underclass perceived as stealing gardening supplies and riding horses down motorways. Travellers were once Irish. Now they are feared by the Irish. They are a protected ethnic group; different, unique, and utterly mobile. Outwardly, there isn’t a trace of traveller in JP Donleavy: the hawk-faced, filthy-rich Anglo-Irish writer who shocked the world with his stream-of-consciousness comedy The Ginger Man (1955) that was dirtier than the Liffey river. Born in the US in 1926 and migrating to Dublin 20 years later, there isn’t even much Irish to him. But there is an inversion. Donleavy romanticised Ireland—even called it home—and he peered into the Emerald Isles like an exile.

Home was always a confusing place for Donleavy. His Irish father once studied for the priesthood but arrived in America “without a pot to piss in”, in Donleavy’s words. His mother, in contrast, swept into New York due to the graces of a very rich Australian uncle. Donleavy’s life was one of relative wealth. His finest memories were learning via a telegram that his grandad had died in Wicklow, the taste of soda bread, and then, after a combatless stint in the US navy, arriving in Trinity College in the wake of the GI Bill.

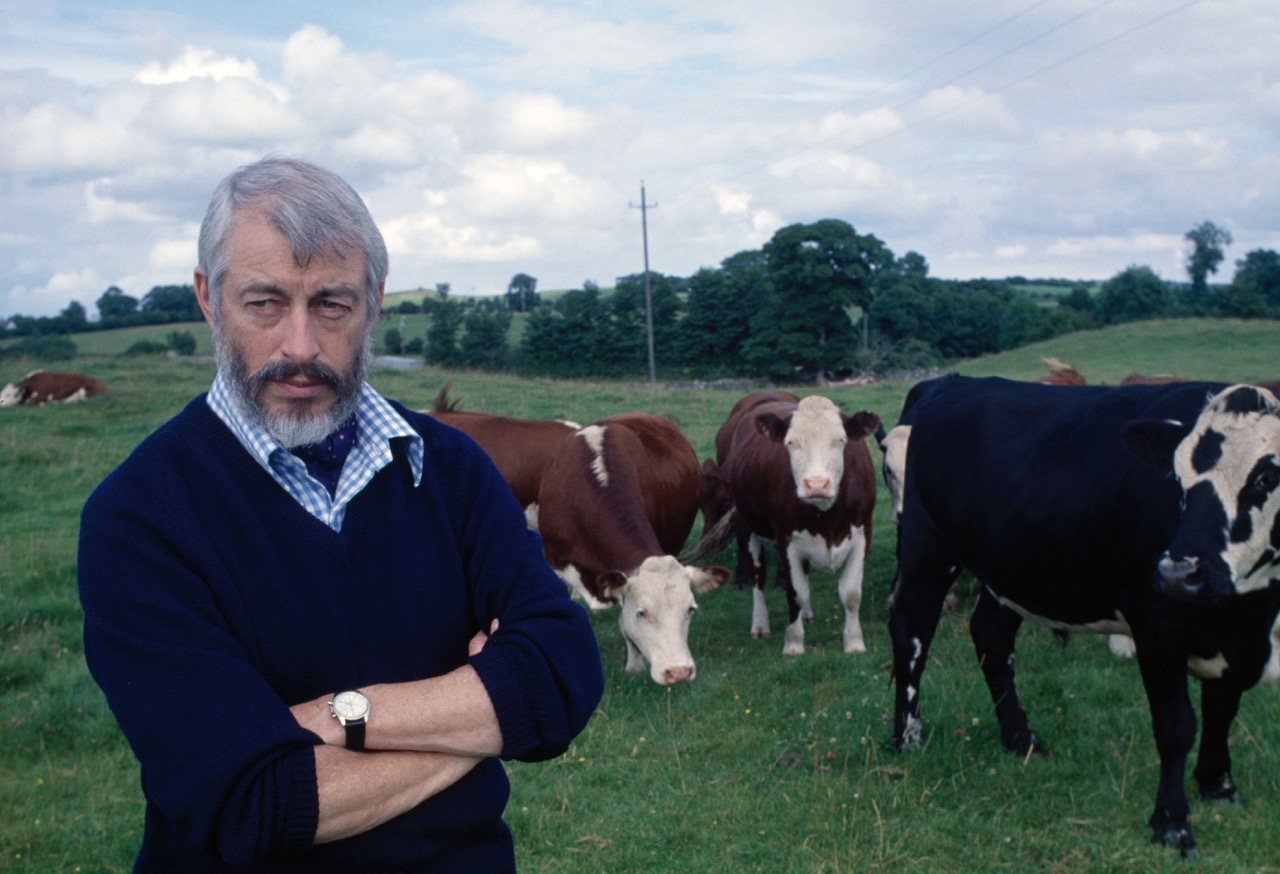

Donleavy in the Irish countryside, 1977. By Terence Spencer.

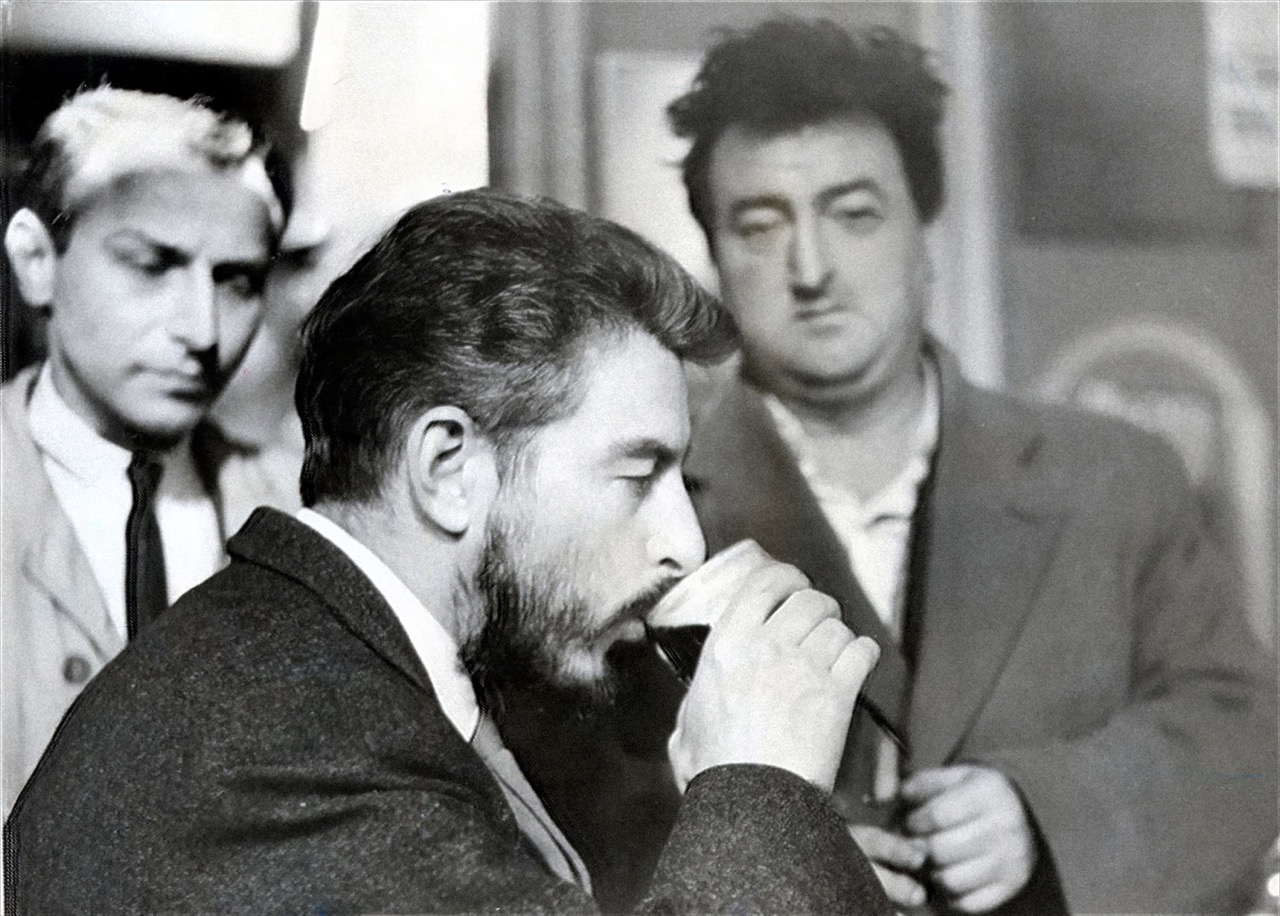

Donleavy’s American dollars made him rich. But he soon discovered his new home was filled with “narrow-minded, bigoted, and bitterly resentful” people. Dublin was poorer, rougher, and more wild than even the Bronx; when teased over his accent (which was, and remained, Anglo-Irish) by the broad Republican writer and fellow student Brendan Behan, Donleavy suggested they fight outside the pub. Behan, who’d already been arrested at 16 for carrying IRA explosives, and had shot two bullets at police two years prior, would have cut a more terrifying figure when Donleavy challenged him. But that was the appeal.

Donleavy—and his new-found habit of wandering slums for fun—had a fearlessness to him. Behan settled the matter with a round of drinks.

Adept at studying filth, Donleavy finished his bacteriology degree at Trinity College. An attempt at painting followed, only for him to quickly realise he wasn’t famous enough to make a career out of it, and he promptly set out to write The Ginger Man in a filthy ghetto of New York. There was no artistic code. Openly, Donleavy worked with the sole intention of acquiring “fame and money”. The distance from Ireland, he later claimed, gave the book clarity.

The story of Sebastian Dangerfield, a wife-beating, narcissistic, insipid Irish-American alcoholic who demands money and sex, was not the makings of a typical literary bildungsroman. But it contained kernels of brilliance: “Some place. What holds it up?” Dangerfield’s friend Kenneth O’Keefe wonders as he peers into another Dublin slum. “Faith,” Dangerfield replies. Donleavy’s stream-of-consciousness style and stout-black humour was described by one publisher as “the finest manuscript we’ve ever rejected”. Getting The Ginger Man into print was a misadventure in its own right. Donleavy’s chaotic tale of post-war student life in Dublin—a book he once described as “celebratory, boisterous, and resolutely careless mayhem”—was rejected by dozens of publishers.

Donleavy (centre) with Brendan Behan (right) and director Philip Wiseman in Dublin, 1959.

Ever dry, [Donleavy] welcomed bad reviews as free advertising.

Behan, by now a close friend, was the one who would help it see the light of day. He had taken a special interest in the work after breaking into Donleavy’s student accommodation in Dublin, spying the work’s early manuscript, and drunkenly scrawling notes on it.

He proposed one interested partner: Olympia Press in Paris.

The good news was that Olympia had published the likes of Beckett and claimed to be interested. The bad news was the publisher ended up filing The Ginger Man alongside its Traveller’s Companion series—better known for publishing erotica. It was hardly surprising.

Later suing Olympia Press (and eventually owning it, openly out of spite), Donleavy made his way back to Europe and, inevitably, to Ireland. In 1967, he returned for good—but this time in richer guise. The Ginger Man’s controversy had laid way to success: even a smash hit broadway led by Richard Harris, who claimed method acting as Dangerfield was the reason he beat his wife. The Ginger Man was banned for decades from print in Ireland, and in Dublin the play triggered an out and out riot before being cancelled. Undeterred and carrying the weary poise of an Anglo-Irish country gent, Donleavy bought Balsoon House, a Georgian manor in County Meath. By 1972, he’d upgraded to Levington Park in Mullingar—a suitably crumbling 18th-century pile with 180 acres replete with Hereford cattle. (Famously, it was the inspiration for James Joyce’s own fictional mansion in Stephen Hero (1944); to keep curious visitors away, Donleavy erected signs that a large bull was present.)

If there was something of the siege mentality about Donleavy, it seemed creatively fruitful. In the surrounding hush of Lough Owel, he wrote—A Fairy Tale of New York (1973), A Singular Man (1963), the Darcy Dancer trilogy (1977 onwards) and over 30 works during his remaining 45 years.

Donleavy’s domestic life was equally layered: his first marriage produced two children before ending quietly, followed by a long relationship with his agent Tessa Sayle. A second marriage to actress Mary Wilson Price came next, ending in tabloid drama when a custody battle revealed that a Guinness heir was the biological father of her children—news Donleavy met with characteristic equanimity. Until his death, he held court in his crumbling Levington Park home—plaster peeling from the walls, his health robust though his voice grew frailer. “My isolation has reached a point,” Donleavy explained four years before his death, “where I do not know how someone could fit into it.”

Some critics applauded the legacy. Peter Ackroyd said that A Fairy Tale of New York is among the funniest novels in recent memory—modern readers might know it as the inspiration for The Pogues’ Christmas single. Home is a strange thing. To the wealthy protagonist George Smith in A Singular Man, it’s a snow-covered trap filled with a family he happily abandons, all for the life of a marbled hotel that’s invaded by street urchins and the public disgrace of profiting from selling morgues. Other critics sniffed. By the time The Lady Who Liked Clean Restrooms emerged in 1998, some reviewers were calling Donleavy a one-trick pony in a three-piece suit. As a writer who based so much in his stories around Trinity, it was quipped that Donleavy seemed to constantly be graduating. Ever dry, he welcomed bad reviews as free advertising. He declared The Onion Eaters (1971) perhaps the worst-reviewed book in literary history, while bemoaning the obscurity of his personal favourite, The Saddest Summer of Samuel S (1966).

There’s a personal touch to Donleavy’s unloved novel Samuel S, a book I don’t think many have picked up. Donleavy was fully at home in the bitter halls of Ireland, a place he described as housing “a small inbred population of highly active begrudgers”. Placing his protagonist Samuel S. in the heart of Vienna, Donleavy seems to speak of his own feelings towards his adopted home when Sam boasts, “When the time comes for suicide, I will have no qualms leaving the Viennese to clean up the remains.”

The Irish-American author JP Donleavy was prolific. Across his decades of work, from novels to essays, readers will find something unique to suit them. These are our favourites:

A Fairytale of New York (1973)

The Ginger Man (1955)

The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B (1968)

The Destiny of Darcy Dancer, Gentleman (1979)

The Irish-American author JP Donleavy was prolific. Across his decades of work, from novels to essays, readers will find something unique to suit them. These are our favourites:

A Fairytale of New York (1973)

The Ginger Man (1955)

The Beastly Beatitudes of Balthazar B (1968)

The Destiny of Darcy Dancer, Gentleman (1979)