Tired, sick and depressed, James Baldwin first came to Istanbul in 1961. A self-imposed exile, fleeing the racism he felt back home in America, there Baldwin found the distance he needed to finish his 1962 masterpiece ‘Another Country’.

In October 2022, a never-before-seen portrait of the writer James Baldwin—gazing patiently from a red armchair, looking tense but also at ease—hung at the far end of Christie’s auction house in London. It was painted in Istanbul, in 1966, by Baldwin’s longtime friend and artist Beauford Delaney, and acquired that same year by Turkish actors Engin Cezzar and Gülriz Sururi (the latter’s portrait was also on display at Christie’s). Delaney’s painting of Baldwin remained for decades within the confines of Cezzar and Suriri’s home, unseen except by their close friends and family, a private memento of a lost and strange time when Baldwin lived, wrote, sought refuge, socialised, fraternised, healed, drank, smoked and thought—as much or even more than he did elsewhere—about writing, about being a writer, about the writing he did and wanted to do and, of course, about Harlem, in Istanbul.

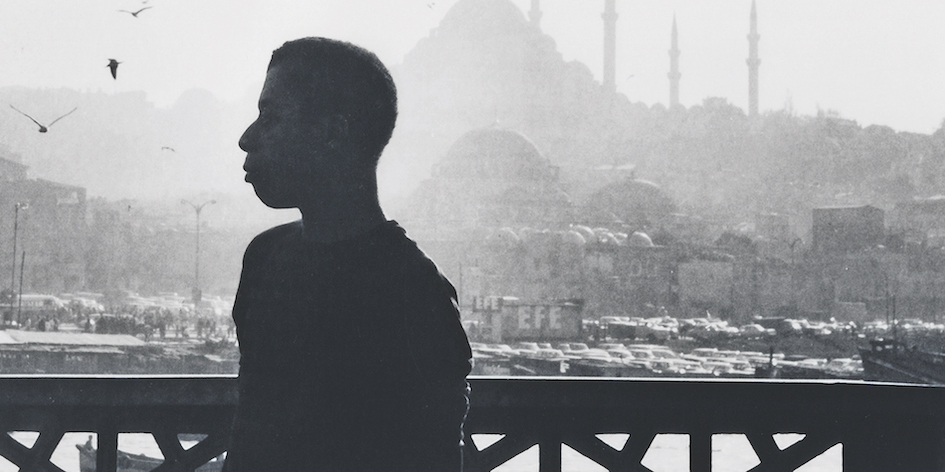

In Sedat Pakay’s 1973 short film James Baldwin: From Another Place, screening at the BFI as part of their season ‘Tear This Building Down: James Baldwin on film’, we see Baldwin as he was back then, towards the end of his time in Istanbul, leaning against the railing on the Galata Bridge, arms crossed as his eyes study the Blue Mosque, on a rowboat rising and falling over the Bosphorus current. We see him in black and white, in daylight and darkness. We see his face crease into a smile with a sense of relief he clearly felt at the time (“Turkey saved my life!” Baldwin once declared). But Pakay’s film also subtly captures the loneliness or torment etched on his face. In a scene of Baldwin getting dressed beside a window overlooking the Bosphorus, he laments, in voiceover: “I don’t really know what I am, politically speaking. I don’t consider myself a leader. I consider myself to be a kind of witness I suppose, I don’t know. But my weapon or my tool is my typewriter, is my pen. And it’ll be a mistake for me to try to play some other role which I really couldn’t play very well.” In exile, Baldwin both tried to flee the racism he experienced at home—as well as the pressures he felt to confront it—and found an outlet in which to write about them. “One sees it better from a distance… from another place, another country,” he says of America, in Pakay’s film.

Tired, sick and depressed, Baldwin first came to Istanbul in 1961. He’d showed up unannounced at Cezzar’s apartment in Taksim, taking him up on an offer the actor had made in passing some months before in New York. Standing small on Cezzar’s doormat, Baldwin carried a battered suitcase and an unfinished manuscript. He’d laboured and suffered over that manuscript for years only to arrive, depressingly, at the point every novelist dreads: the fatal realisation that time and effort have yielded an unworkable story and empty characters. Baldwin called the manuscript “unpublishable” at the time and went as far as to say that it had brought him, “to the point at which many artists lose their minds, or commit suicide, or throw themselves into good works, or try to enter politics.” With time and Cezzar’s help, however, Baldwin’s mental and physical health improved and so, too, did his novel. Over several months, he used his pen like a surgeon, taking a scalpel to his manuscript and re-writing, re-working, re-thinking Another Country (1962) entirely.

It’s hard to tell to what extent being in Istanbul, or Istanbul itself, enabled Baldwin to finish Another Country, let alone to transform it from something he considered a failure into the bestseller it became. But gestures to the city are everywhere. In Pakay’s film, Baldwin is seen holding up a translated copy of the novel in Istanbul, smiling hard and wide for the camera. The novel itself ends with a date: Istanbul, Dec. 10, 1961. And, of course, Another Country was the book he claimed almost killed him, whereas Istanbul was (exaggerating or not) the city he credited as his saviour. What is potentially more interesting, though, is the possibility that what Istanbul really offered him was not a refuge but a lack of definition or clear distinction. In America, he was defined fundamentally by his race and sexuality. But in Istanbul, Baldwin found a place that (at least on the surface) rejected neat typecasts. Istanbul was a city in between, both East and West, European and Asian, modern and ancient, not really, in fact, a city at all, but many, at the heart of so many former empires and on their margins; a place that truly felt—as maybe he was trying to capture in writing—like another country: mysterious, ambiguous, elusive.

By the end of his time in Istanbul, Baldwin had created or helped create the kind of creative refuge that reminds us of others like it, from Ernest Hemingway’s Paris to Leonard Cohen’s Hydra. He was invited to parties and later hosted them. He threw lavish get-togethers that included the likes of Marlon Brando, Harry Belafonte, and author Alex Haley, and staged theatre productions with other writers. All of this feels strangely appropriate when considering that Baldwin first arrived at Cezzar’s apartment in Taksim as his host was throwing a party and was immediately introduced to Istanbul’s intelligentsia.

Still from I Am Not Your Negro (2016).

In Istanbul, Baldwin found a place that (at least on the surface) rejected neat typecasts. Istanbul was a city in between, both East and West, European and Asian, modern and ancient, not really, in fact, a city at all, but many, at the heart of so many former empires and on their margins; a place that truly felt—as maybe he was trying to capture in writing—like another country: mysterious, ambiguous, elusive.

Ramzi De Coster

Whether Baldwin was at home or at ease or even “healed” in Istanbul or not, the question remains: to what extent did Baldwin’s time in Istanbul really influence his work, which never actually featured Istanbul? Was Istanbul just a break from the pressures imposed on a successful writer and an activist in the civil rights movement (as Baldwin claims in Pakay’s film)? Or was it simply a place to get clarity on a failing novel? Was it really a literary refuge? Or a refuge at all? Baldwin once wrote that he felt that the world itself was “no longer liveable.” Seeing him on screen, pausing between sentences, between thoughts, and revealing the flashes of turmoil on his mind at the time, the romantic notion that Istanbul saved or transformed him falls apart. Maybe it was not a place, not another country, that “saved” him, but the fact of writing itself that did this, which he seemed to be able to do more easily in Istanbul simply because he was doing it from afar.

Delaney’s portrait of Baldwin was ultimately sold on October 14th, 2022, and moved, once again, from the place where it had been on display for decades, elsewhere. At first glance, the painting is simple and uncomplicated. The stark contrast in colour and the fixed look on Baldwin’s face is interesting—but maybe less so than the story behind the painting. On closer inspection, however, a strange and important detail reveals itself. Baldwin is silhouetted against what looks like a hazy, razor-thin skyline of Istanbul, painted in a light shade of early-morning blue. It recalls another shot, just like it, from Pakay’s From Another Place. In the latter image, Baldwin looks out towards something we can’t see, his profile in the foreground barely perceptible against the misty, near-indiscernible outline of the “third hill” of Istanbul in 1966. Frozen in time, the image calls us back to that elusive era when Baldwin wrote in Istanbul and, however much he was influenced by it, became a part of it.

Tear This Building Down: James Baldwin on Film is at BFI Southbank until 30 November 2024. I Am Not Your Negro and If Beale Street Could Talk are available to stream on BFI Player.