The Nickel Cinema is now open and is offering a delightful assortment of exploitation and b-movie madness.

‘I keep trying to get someone to use the phrase “troubled cinema proprietor” for me, but no one’s done it yet,’ Dom Hicks says, sitting behind the downstairs bar of his aforementioned cinema. The Nickel – a new, 37-seat micro-cinema in London’s Farringdon, with one screen and a bar and a shop full of arthouse and cult movie ephemera – is a rarity in this bland, corporate part of central London. A hub for office buildings, Prets, and little else, there’s not much cultural life in this part of the city. That makes it all the more strange and wonderful that Hicks has turned his passion project for cult films into a bricks-and-mortar venue. “Troubled cinema proprietor” would certainly add to the lore of the self-consciously transgressive programming at The Nickel, which intentionally and defiantly spits in the eye of expectation.

Open for hardly two months, they do what they say on the tin: purvey near-nightly cinematic sleaze, grindhouse, and all the beauty of Scala Cinema past. The Nickel’s curation so far has seen everything from forgotten exploitation films of the ‘Nam era to direct-to-video body horror. They try to screen one 16mm film per week, in August planning to bring in musical accompaniment for Tod Browning’s silent horror The Unknown (1927).

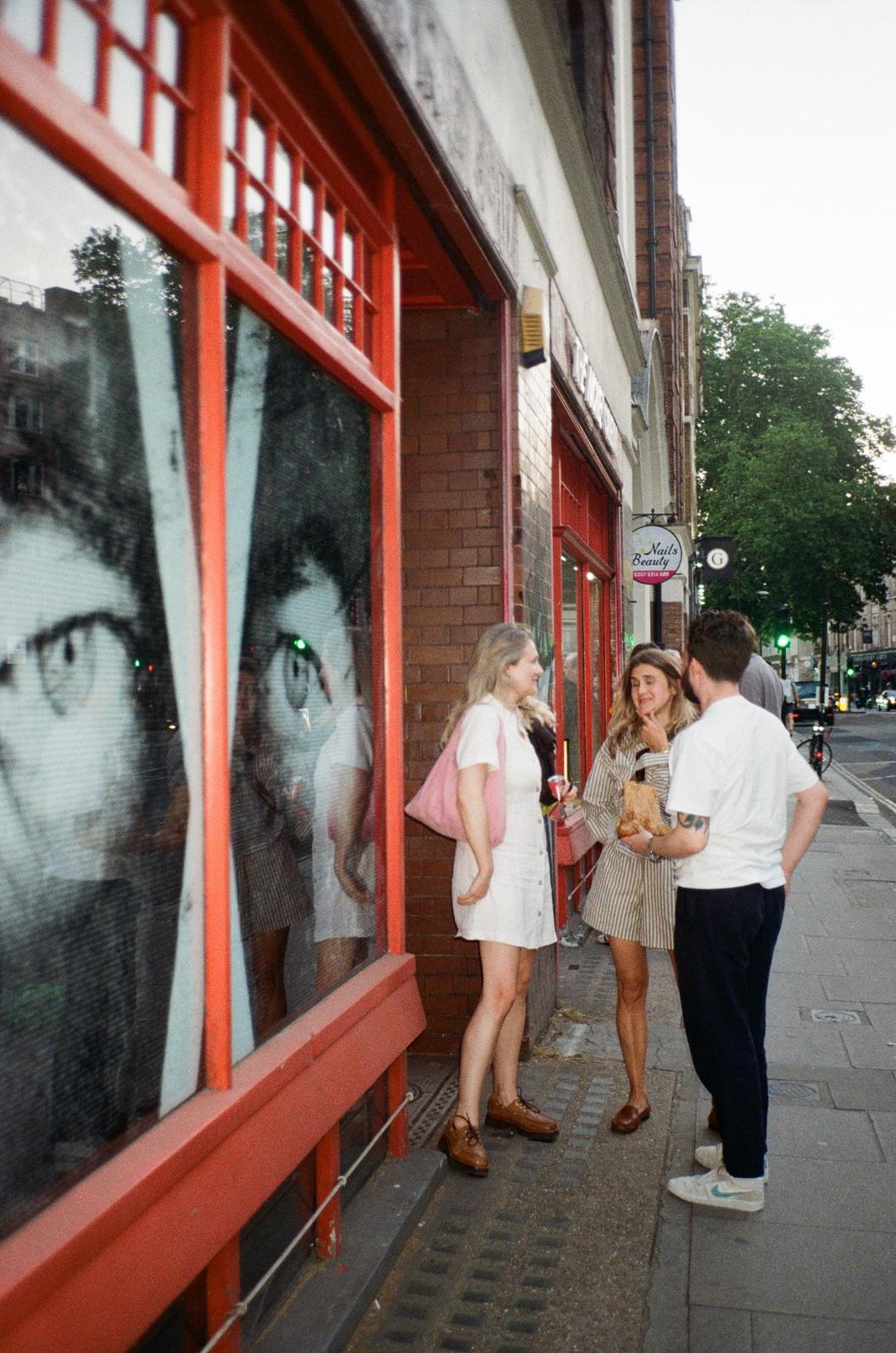

As I speak with The Nickel’s founder, I notice the infamous Playgirl centrefold of a hairy-chested, near-naked Burt Reynolds grins down at any would-be customers on the wall behind him. Those would-be customers seem not to be able to get enough, either: a young man who looks like a student comes to the door to softly ask if he can take a look around quickly, even though the venue is shut. People often call inside just to peer around at this new little gem in the neighbourhood, whether it’s open or not. Hicks reminds me to lock the door so we don’t get interrupted too many times by curious passersby.

“The Nickel’s curation so far has seen everything from forgotten exploitation films of the ‘Nam era to direct-to-video body horror.”

Christina Newland on The Nickel Cinema

The Nickel is, first and foremost, a labour of love. As the sole proprietor of this cinema, he says he often thinks of himself ‘like Bugs Bunny when he plays baseball with himself’ in Looney Tunes: he’ll take tickets at the door, run over to lace 16mm film through the projector, and sweep up popcorn. He has the help of a handful of dedicated volunteers at the bar and elsewhere, but it still means being present every evening. He idly, jokingly, wonders if he should start sleeping here. He thinks about moving his cats in as mascots. ‘I massively underestimated the challenges, because I’d never run a venue or done anything like this before. But that naivete probably helped me,’ Hicks says. ‘I’d have been too overwhelmed otherwise.’

There’s an impressive collection of bijou movie items in the shop upstairs – old magazines boasting stills from Sam Peckinpah’s nihilist western Bring Me The Head of Alfredo Garcia, books of film criticism by Pauline Kael, a home video selection of blu-rays featuring everything from B-movie hilarity Slugs to Vittorio De Sica’s Garden of the Finzi-Continis. Turns out that it’s all Dom’s personal collection. Selling it is painful. ‘I do often say no, and it often ruins my night when I’ve said yes. So it’s a bit eccentric, but we are hopefully partnering with DVD labels and getting some real stock,’ he says. ‘And it feels nice to share something with someone else who’s gonna love something. It’s a whole part of the physical media thing, right? Then it goes from one shelf to another, from one pair of hands to the other. There’s something charming about that.’

‘If you come in here and you’re offended by what you see, you’ve only got yourself to blame,’ Hicks laughs. He points at the Burt Reynolds centrefold behind his head. ‘If you don’t look at Burt Reynolds beaming at you, full frontal, and know you’re in the wrong place….’.

Owner Dom Hicks on The Nickel Cinema

Tonight, the programming choice is Bob Fosse’s lacerating 1979 musical All That Jazz, a strange and vivid, semi-autobiographical story of a theatre director striving for artistic greatness while nearly killing himself with booze, cigs, and dexedrine. Lurid and strange, this is actually a fairly mainstream choice by The Nickel’s standards. But it’s also characteristic: idiosyncratic, throwback, probably 1970s or 80s, genre-oriented with a twist, and a movie people have underappreciated for many years before its day in the sun. From spaghetti westerns to creature features, maligned Liz Taylor vehicles to communist film noirs, there’s an exuberance, depth, and variety here. And it doesn’t always mean perfection.

‘For me, I sometimes wait for a dodgy moment or a thing that doesn’t connect and or a tonal inconsistency. That’s what makes the work human. For me, that’s what makes films human. Those little odd moments or the strange delivery of a line.’

We spitball for a while about what makes a ‘perfect’ film, and why – in the face of so much by-committee corporate streamlining – imperfect can be much more interesting. ‘Kubrick, for example, made basically perfect films. But then when it comes to the independent, kind of shaggy dog films that we show a lot of here… things stay in your mind because of a moment you can’t explain, or a strange decision that probably was a mistake, but it means that you’ll never forget it. That’s become increasingly rare. I think that would get weeded out during the process these days.’

We go off-piste and off-record here and again, chatting about Tarantino’s New Beverley Cinema in LA and the vagaries of collecting 16mm film, but eventually come around to a loaded, potentially tricky question. A whole lot of intentionally challenging, boundary-pushing, and antiquated attitudes appear in some of the films from this era we both love. ‘What I look for in an artist is confessional, is them exposing their shortcomings, their fears, their paranoias, their failures as a human,’ Hicks says. ‘Not how right they are, how correctly they see everything. That’s dull, I think.’ We agree, for instance, that Sam Peckinpah was a chauvinist, but his films reveal something about the nature of that chauvinism — even if, at times, by accident. ‘I think people are actually quite critical and intelligent. They understand the history of things. People are not surprised to hear that the 70s were a problematic time.’

‘If you come in here and you’re offended by what you see, you’ve only got yourself to blame,’ Hicks laughs. He points at the Burt Reynolds centrefold behind his head. ‘If you don’t look at Burt Reynolds beaming at you, full frontal, and know you’re in the wrong place….’.

That point is a salient one. Ultimately, I’ve come to talk with whoever was responsible for this project because it feels like their taste sprung from my own brain. The siren call is too strong to resist: I am the core audience for The Nickel. That is: intense, weird, obsessed by cinema oddities and 70s freakiness, keen to be shocked or enthusiastically dissect a film that only the cinephile treasure-hunters have also seen. Dennis Hopper’s blue-collar subculture nightmare Out of the Blue, for instance, where a disaffected pre-teen Linda Manz runs around shouting ‘Kill all hippies!’. Or Straight Time, with Dustin Hoffman as an ex-con trying and failing to stay out of trouble, adapted from Eddie Bunker’s remarkable, raw novel ‘No Beast So Fierce’. There are people who care about these things, and there aren’t very many of them. And so we should flock together.

‘I would love to have film professionals here to host workshops. Stuff on loading and shooting 16mmm, screenwriting, acting. Nothing too typical or formal, but super accessible. Because part of the problem with what’s getting made now is — and it’s happened all across the culture — this bourgeoisisation of everything. Super affluent middle class people, or all the same people, are making the same types of film.’ he says. It’s an ambitious gambit, but then, I’m not surprised at this point: The Nickel already plan to launch their own podcast and are midway through publishing their first zine.

Hicks points out that it’s a sign of how ‘anemic the culture is’ that so many people seem so excited about his little screen in a little bar. ‘A project like this is kind of born into precarity, in a sense. London doesn’t seem to want this. The people do, but the city doesn’t. You feel that you’re doing something wrong by trying to build an art space, when all art spaces around you are being closed down or threatened,’ he says. And that’s exactly why this dash of colorful cultural mayhem in the colourless humdrum is exciting. In an era where genuine subculture cannibalises and gentrifies itself before it has a chance to flourish – where imperfection feels like anathema in the face of AI – there’s incredible solace in the idea that like-minded people might gather in a basement to drink cheap beer and watch some weird movies.