Gen Z and Millennials find comfort and intrigue in shows like Industry, Mad Men, Emily in Paris, Suits or Grey’s Anatomy. Why? Because we yearn for stability, says Haaniyah Angus.

Would you consider Industry a fantasy? Fantasy is defined as a genre set in an imaginary universe, with any locations, events, and people distanced from the real world. HBO’s investment banking drama is admittedly not based in an imaginary world, but for fans of the show, the finance world has become an enthralling break from our reality, in which our relationship with work has become even more strained. Industry exists in an alternative reality where you’re on a trading floor from the early hours of the morning until late afternoon, followed by pints at the pub and if you’re feeling cheeky, a bump with an invitation to a club where you dance all night until one you realises you’re meant to be in the office in a few hours for a meeting with a client. Industry is sexy, chaotic, anxiety-ridden television, and most importantly, it’s become an essential part of the work culture TV canon.

The show centres on a group of recent graduates competing for a spot at a prestigious banking firm, Pierpoint & Co. They’re quickly thrust into the ruthless inner workings of banking and find themselves pushed towards choices that fundamentally change them—almost always for the worse. Industry is alluring with its fast-paced narrative and nonchalant relationship to sex, drugs and fucking people over, but beneath its showyexterior lies a fundamental truth—to be young, successful and happy in today’s economy is almost impossible without sacrificing your personhood. In the first episode, this becomes clear when Hari—one of the internship cohort—dies from stress and lack of sleep. Much like the institution itself, the show simply moves on and gets right back to work, just with one less mouth to feed.

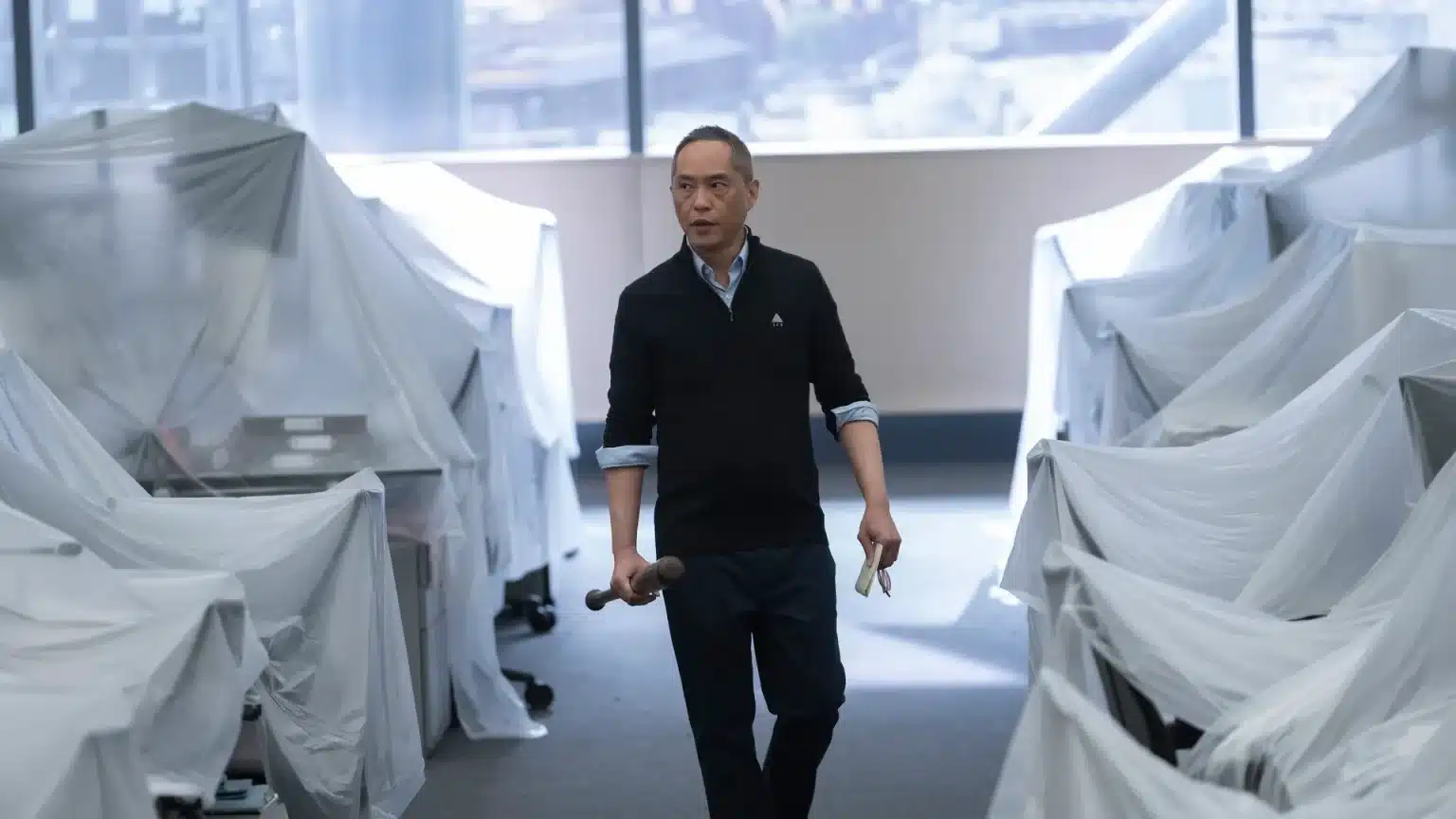

INDUSTRY (HBO)

In the 1990s, satirical depictions of office culture in films such as Office Space, American Psycho, The Matrix and Fight Club sought to examine the lethargic and mundanity of typical 9-5 jobs. But as culture writer Engwari explains, the mundane is now appealing. “When we used to think of the office from media depictions, the first thing that came to mind were grey cubicles, boring co-workers and managers droning on. Now, we have people aspiring to that as a status symbol that’s so much more attractive than taking the risk of being creative or freelancing.” It may seem ironic to older generations that Gen Z and Millennials find comfort and intrigue in shows like Industry, Mad Men, Emily in Paris, Suits or Grey’s Anatomy. The youth—aka people in their mid-20s and 30s—apparently yearn for stability.

Think about the recent obsession with journalists from 1990s an 2000s Romantic Comedies, such as Jennifer Garner in 13 Going on 30, Kate Hudson in How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days or even Carrie Bradshaw in Sex and The City. Today, being a writer means little-to-no stability and money because of the lack of funding within journalism. When you watch entertainment like Sex and the City, you get a taste of the good old days when you could get paid $4 a word at Vogue. But unlike journalism, there is always money to be made in finance.

For Industry fan and writer Becca M*, their relationship to money makes the characters so relatable. “We live in this culture of zero-hour contracts, so to have a set amount of hours and a regular salary feels like a privilege. That also plays into Industry because you have all these characters like Rob (Harry Lawtey), Harper (Myha’la Herrold), and even Yasmin (Marisa Abela), who grew up with a very difficult relationship with money or never having control over it. Pierpoint is a balm for them because they get a lot of money for this work, and it’s finally theirs.”

The characters live and breathe Pierpoint & Co. Their lives and relationships centre around work, betting on trades, and striving to break free of their pigeonholes. Yasmin is a nepo hire, Rob is a social climber, and Harper has faked her way into the job of her dreams. Their choices in fashion, hair styling, hobbies, and romantic relationships signify an attempt to centre work in their lives. They are the ultimate workforce until something cracks one way or another. In the case of Yasmin and Rob, it becomes clear they’re not made for Pierpoint, but Harper is, and she’s punished for that.

INDUSTRY (HBO)

Industry is often compared to HBO’s juggernaut hit Succession, but I believe it would be more accurate to compare it to Mad Men, a show that parallels the relationship between Eric (Ken Leung) and Harper via the haphazard mentorship between Don Draper (Jon Hamm) and Peggie Olson (Elizabeth Moss). Don and Peggy’s dedication to advertising ruined their relationships, much like Eric and Harper’s dedication to the institution (and later on corporate espionage, as Harper puts it in season 3), leaving them with fragmented relationships towards those willing to show them love and care. It’s an apt metaphor for what happens when you let work become your whole life, especially when said work and workplace are toxic to an extreme level.

“When you watch entertainment like Sex and the City, you get a taste of the good old days when you could get paid $4 a word at Vogue. But unlike journalism, there is always money to be made in finance.”

Haaniyah Angus

Hibaq, a long-time fan of the show, explains that the toxic workplace culture of a company like Pierpoint has become a norm in today’s economy. Pay inequity, poor working hours, and lack of advancement within corporate structures have left young people stuck in a cycle of making ends meet with jobs that would have afforded them a house less than thirty years ago. “I think a lot of people watch it because we’ve recognised the toxicity, and it’s also available in our own workplaces to a lesser degree, or maybe even to a worse degree in a different way. I might not know somebody like Rishi (Sagar Radia), or I might not know somebody like Eric (Ken Leung), but I can pull bits from them and see those reflections in other people I’ve worked with. The show does a really good job of making that apparent without dumbing it down.”

Industry knows its viewers might not understand the intricacies of finance jargon and trading lexicon. Its creators, Mickey Down and Konrad Kay, state, “we want our stuff to be more literate [than Netflix shows] because it’s a huge investment of our time. It has to be more than just valium for your brain while you cook dinner.” But what’s key to Industry is that it’s in no way romanticising the office as some safe haven of capitalism. You feel the burden of working within the finance industry and even its characters’ trauma. They’re losses, anxieties, embarrassments and, most importantly, highs when they realise that maybe they won’t be fired that day after all is what makes us stick around. An element of thrill is found through watching what might be the worst day of a character’s life. For writer and director Katie D*, the reason may simply be that no one works somewhere that exciting anymore, “When I rewatched The West Wing while hating my job, I realised that at its core, it’s a fantasy show about your job being interesting every day.”

Maybe we need the fantasy, maybe it’s setting us back, or maybe the team behind TV’s latest hit are just that good at making us forget just how dull working can be.

*Some names have been anonymised.