The following paragraphs contain an interview with the American playwright, actor, screenwriter, and now filmmaker, Jeremy O Harris. This was conducted at the beginning of December 2024, while Harris was preparing to organise the next edition of the Williamstown Theatre Festival, and not long after the American presidential elections.

The context of time and place is important when speaking to Harris, who—even through judging his social media activity alone—is strongly opinionated and brings a political narrative to whatever feeds the zeitgeist.

As you will discover toward the end of our conversation, we spoke about Donald Trump and how the then president-elect has influenced an upcoming project of his, as well as touching on the war in Gaza and the pitfalls of virtue signalling. I would also have liked to discuss with him the case of the assassin Luigi Mangione, whose internet fame piqued Harris’s interest (as is evident on his social media). Mangione’s story would’ve made a fascinating Harris-esque theatrical satire on America and on the state of internet culture, and is perhaps one we’ll get to see in the future.

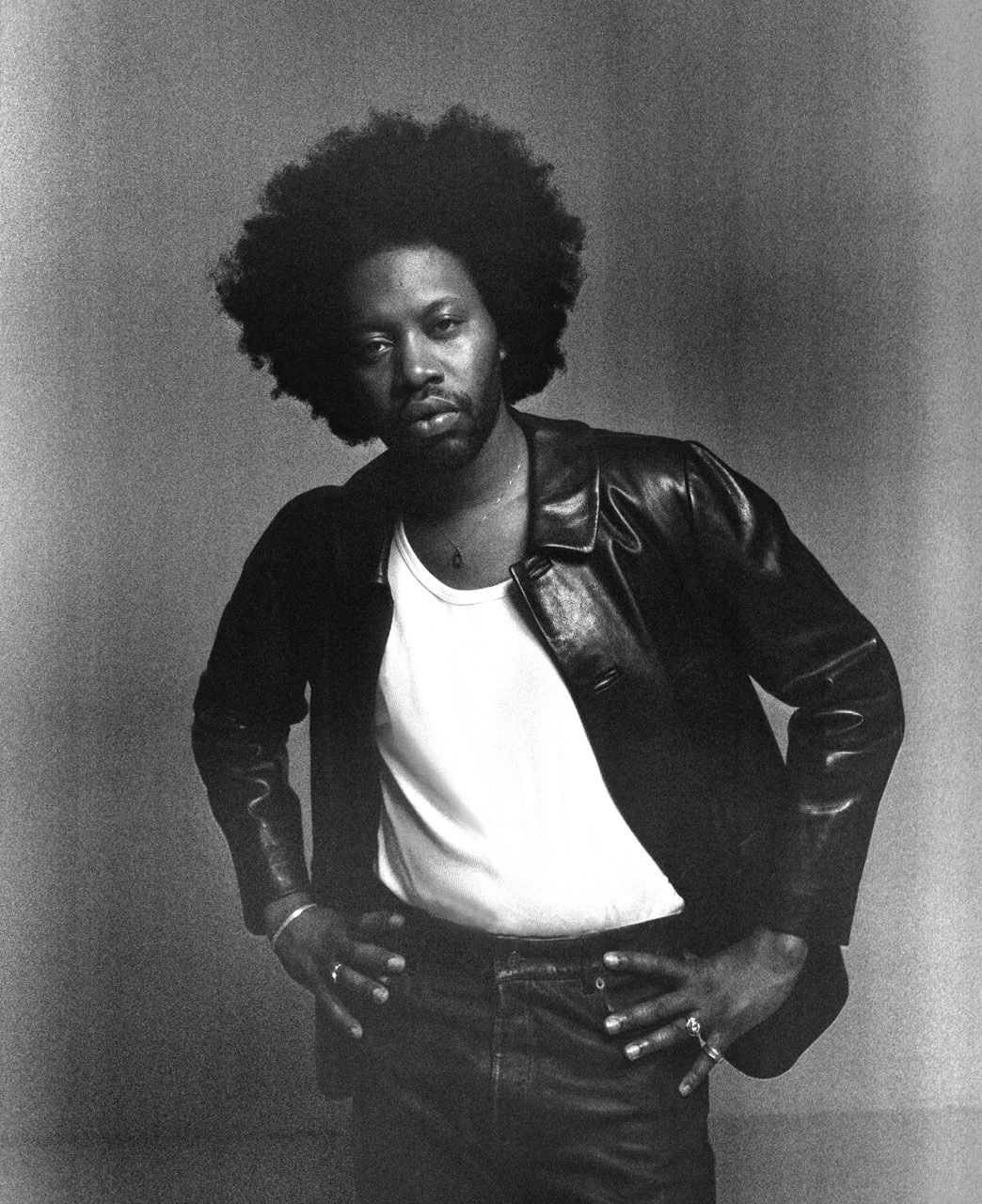

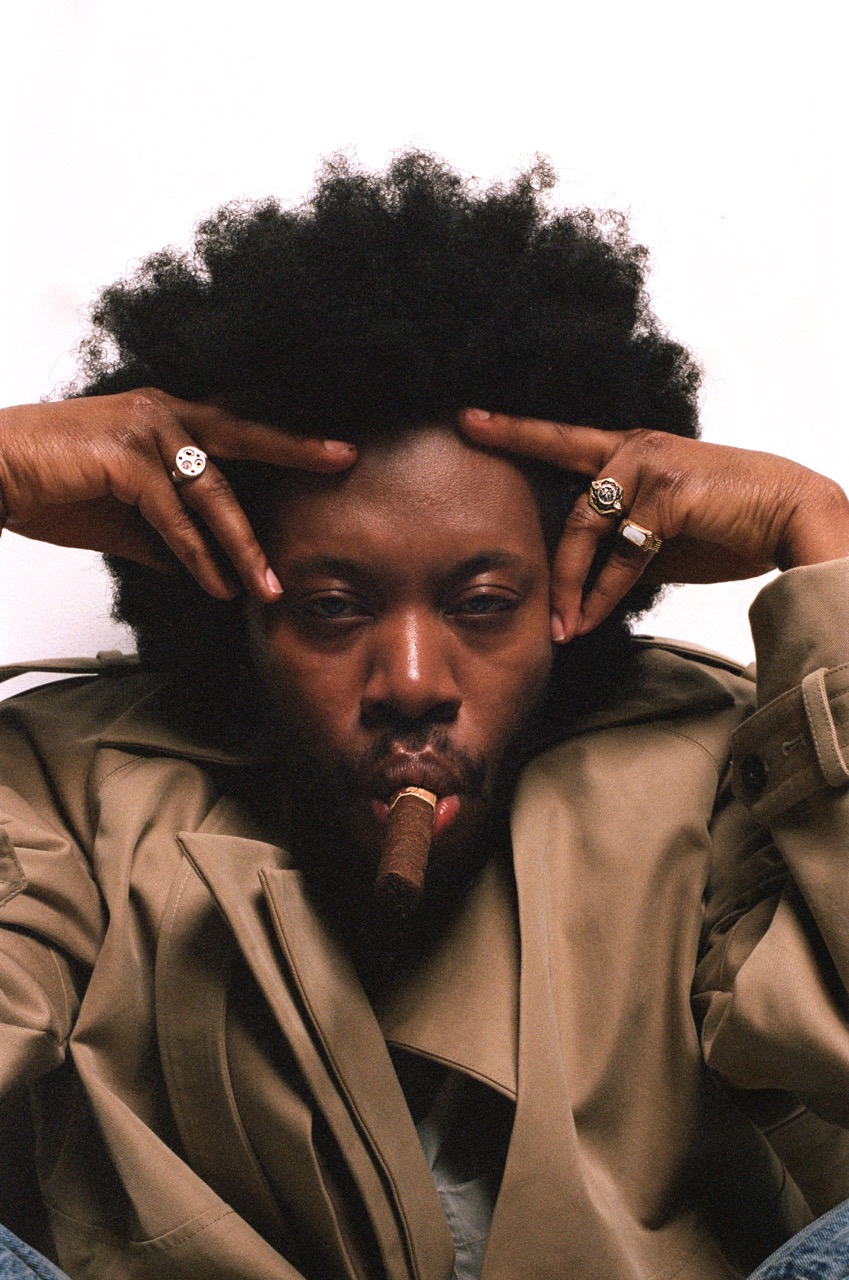

Harris, who is gay, Black, and from the American South, is—aside from being a uniquely talented, award-winning writer and social observer—excellent at conveying an image of who he is, and how he wants us to perceive him as a personality. During our interview, he expresses the value of being a salesman as a part of becoming a successful artist, and I find this especially important to his work. He is, to my mind, the most authentically modern of our present-day writers, owing to the fact that he straddles the line between playing the role of an influencer—a term I’m sure Harris would hate—and an intellectual in the most serious sense of the word. Like one of his heroes, director and filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles, he places himself at the centre of his work, excavating his individualism as a person in America for us all to witness—even if it is sometimes ugly. He is driven by a sense of responsibility (that can manifest as frustration) to influence change in the arts, and what he frequently calls the “canon”—his idea of an American cultural lineage, of playwrights, artists, and even Black musicians, that he demands to be a continuation of. At just 35 years old, Harris has done more than most people to add to the canon. And, as is evident in our conversation, he still believes he has a lot more to offer.

Jeremy O Harris went out last night. The multi-hyphenate, mostly playwright, famous for the award-winning Broadway productions Slave Play and “Daddy”, was celebrating a new musical by two friends, Patrick Foley and Michael Breslin. “I think it’s going to be the sickest musical of the season,” he beams.

Harris is speaking to me at home in New York, on a quiet street off of Chinatown. When he’s not on the road (which is often) his time is spent between the city’s artsy crowds and with the beau monde at elegant galas. He speaks like a turret-gun and has a magnetism that I’ve personally witnessed light up a room: once in London, where the six-foot-five, wiry Harris was doing the rounds at a dinner for a fashion house, stooping to shake hands. Then, in Cannes, during the film festival. And again in London, on a rainy night in Camden outside Koko.

Like Oscar Wilde, or other prolific social observers (let’s face it, he’s also a socialite), this aspect of Harris’s life is something he is not only good at, but one that serves the craft. His charisma can be read off of every page of Slave Play or his selection of smaller diary plays. “Being social is something that can be looked down on,” he tells me. “The more professionalised you become, the more people see you as unserious when you are at a dinner or party.” A week later, speaking with my editor, we tried to understand his use of the word “professionalised”. Did he mean the more he was being reconditioned or accepted? Harris sometimes still describes that world as though he shouldn’t belong; as though he is a rebellious outsider.

“I see going to these parties as a part of the artist’s journey,” he says, mentioning the journals of other great authors who engaged with this lifestyle. “That sort of socialising has fuelled my practice in a grand way.” Overhearing, and remembering, a conversation at a dinner party is where so much of his dialogue comes from. “I’m like a magpie.”

Born in 1989 into a military family, Harris moved around the US before settling in Martinsville, Virginia. He grew up modestly, raised by a single mother who ran a hair salon. She remains one of the closest people in his life.

There’s a saying in the South of being among ‘Grown folks’ business’, he tells me. “My mom had me when she was 19, and so I was always ‘under her’. She allowed me to be around grown folks’ business and sit at the table and listen in on the gossip. I think a lot of young gay boys who are close to their moms have the same experience.”

Harris’s mother, like my own mother, is a hairstylist. It’s an aspect of his upbringing I relate to. We discuss life in the salon; the characters who drop in, and the conversations and vulnerabilities people readily give up, even in the company of children. He credits those times with his talent for storytelling and an emotional maturity that is derived from patiently sitting and listening, and I feel the exact same way. The hair salon kept me inquisitive. In the opening pages of Slave Play, he acknowledges this part of his childhood by thanking his mother: “To mom, who taught me how to listen.”

“Oftentimes being in a hair salon is like being at a psychiatrist’s office,” he adds. “The amount of wild vulnerabilities that you witness, they reshape you. Those stories were the soap operas or novellas in the middle of my day.”

Harris did not always want to be a writer, but he was a voracious reader, absorbing as much information as he could from books and plays to outsmart local bullies. His childhood dream was to become a lawyer, he tells me, but a therapist suggested he write down the conversations he was hearing from the people he was describing, and he realised he could speak them verbatim. It’s then that his inner magpie began to awaken (a moment he immortalised in a monologue from his hardcore satire Yell). “The minute I started writing, the whole conversation came out,” Harris remembers. It remains the method to his practice: first, the dialogue is put to paper, then the framework for an idea he wants to explore emerges from it. This is still how Harris writes a scene, and forms the basis of his unique genre of hyper-personal “diary plays”.

This led him to enrol as an actor at The Theatre School at DePaul University in 2009, where he was given an undergraduate assignment to find a monologue for someone who shared his identity. He remembers finding this harder than other students, and so he wrote his own instead. “In that play, I built out this monologue of a character who is Black, and gay, and from the South, and is a cinephile who does a monologue of how Shadows is his favourite Cassavetes movie.” When his peers discovered he had written the monologue, he was encouraged on that path instead (Harris was cut from the DePaul program after a year).

Loud, flamboyant, and usually dressed in colourful haute couture, Harris was able to court attention. Eventually, through an ability to get into the right parties, and through a network of contacts he made while living first in Chicago and then Los Angeles, he engaged with a creative scene that led him to a residency at the MacDowell Colony. There, he wrote “Daddy”, his subversive depiction of a toxic relationship between a wealthy collector and a young black artist. The success of “Daddy” was used, finally, to apply to the prestigious Yale School of Drama in 2016. While submitting, he presented the idea for Slave Play, and was accepted to enrol. It was a divisive success on campus, and was being taken on by the New York Theatre Workshop and presented as his professional debut, billed in 2018 as an “antebellum fever dream”.

His father, or rather father figures, were all coincidentally in the military. “Military men have encircled my entire life. My biological dad was never in the picture. And then I had a stepdad in the military, and that guy also sucked.” He describes the military as a pipeline for people who grow up Black and working class, and want to find an escape. “It becomes a great outline for them to become bad adults. But at least they have money…” he states. “There are other ways, though.” And for Harris, there have been many: a playwright, a filmmaker, an actor, a producer, and now the newly appointed head of Williamstown Theatre Festival.

Because Harris fits in with so many circles—from fashion crowds to Hollywood and avant-garde creatives—he was the prime person invited to be the creative director of the next Williamstown Theatre Festival, founded in 1954. When we speak, it is taking up most of his time; more than he expected when he signed up.

“Williamstown was very mysterious to me,” he admits. “I was an O’Neill Theatre Conference playwright early on. They were my big supporters. No judgement, but I had written Williamstown off as this place that wasn’t interested in me.” When the opportunity came up, it arrived at a crucial turning point in Williamstown’s history. Young interns and apprentices, who had traditionally worked for low or no payment, publicly announced that their labour was misappropriated. The model that had worked for Blythe Danner and Gwyneth Paltrow to act in the past didn’t cut it in 2024, and they were seeking a new, progressive vision. “That heyday had sort of disappeared and they were wondering if the company was going to exist.”

Harris had been offered plenty of opportunities to lean into his producerial interest before, but Williamstown felt right and less like a risk. “I didn’t want to be scapegoated for failure. Because I do think I have good ideas,” he adds. The magpie immediately opened up his contact book and started calling people whose work he wanted to see in a big, dynamic way. One of those is the highly popular English songwriter FKA Twigs, who is a part of Harris’s network. “I ignored the practicalities,” he admits. “I’ve said yes to five shows on the main stage, and it can probably hold like two of them. We’re shooting for the stars.”

It’s typical of Harris to either do something on his terms, or to not do it all. He shouts out the festival’s managing director Raphael Picciarelli, who he credits with keeping relevant parties happy. His ambitions (both personal and professional) can seem demanding, and there’s a feeling that because he works so hard, he expects everyone to keep up with him—even if it is unreasonable to do so. “Raphael is phenomenal in that he has never made me feel like a real ‘no’ was coming,” says Harris. “Even though I imagine he’s doing some fighting on my behalf. He invisibilised his labour in a way that has been helpful for morale. Gung-ho, you know? He’ll smile and then behind his eyes, you can see: oh fuck, how are we gonna make this work? But we will.”

Before meeting Harris, I watched an early screener for his upcoming HBO documentary Slave Play. Not a Movie. A Play, which takes audiences behind the scenes of Slave Play. He asks about the reception of a screening in London, organised by Steven Hanley and the Deeper Into Movies platform. “What did you think?” he asks, genuinely curious. A moment of tension. I reply that his documentary is a moving, experimental insight into Harris’ work, not just as a playwright, but as a communicator, and as a man with grand ideas who understands that the scope of his work can, and should be, bigger than himself. He is satisfied with this answer, as a first-time filmmaker. But I also sensed that Harris is self-conscious of his output, especially with new mediums. “It took me a second to find my voice,” he explains, modestly. And then: “I don’t care if it looks like any other HBO documentary.”

The documentary, which recently won at the highly prestigious Cinema Eye Honors for Best Broadcast Film, follows the making of Slave Play, the production that changed Harris’s life. Regarding his most famous work, which was first performed at 29, and which follows interracial couples undergoing “Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy” due to a lack of arousal with their white partners. “I wanted to make a classic piece of American realism, which disgusted me in writing. But I wanted to make it feel experimental and expansive, and I wanted to break the form so I have the game play with the audience.” His breakthrough on sexuality, race, and identity in 21st-century America is famously subversive and divisive, and has been known (as we are shown in the documentary) to drive some audience members into fits of anger. Provocation is a trope that Harris has built a part of his reputation on. It fills theatre seats. But I also get the impression he enjoys toying with the audience’s expectations. “I like playing that game, where they expect one thing and then it is entirely different,” he says with a grin.

For most critics, Slave Play heralded an undeniable new star—it was nominated for 12 Tony Awards— and Harris became prolific. Yell followed, based on his experiences at Yale, and then “Daddy” in 2019 (I saw it with a stunned audience at the Almeida Theatre in London). There were also glimpses of Hollywood interest when he co-wrote the script for A24’s Zola (2020), directed by his close friend Janicza Bravo, and translated from a 148-tweet thread.

While Slave Play was on Broadway, he completed and performed in the intensely personal and avant-garde diary play Black Exhibition at the Bushwick Starr theatre in Brooklyn. The central character @GARYXXXFISHER, The New Yorker suggests, shares some of “Harris’s particularities”. Harris tells me: “I was trying to think about what it meant to be a queer artist on display.” Many of his most personal works involve exposing himself and his vulnerabilities out to be judged, or reasoned with, by audiences.

In 2019, Harris would travel between Broadway for Slave Play and Brooklyn for Black Exhibition—a welcome change of pace. “This freed me up from the constraints of what commercial playwriting can be,” he says. Always in need of variety, the documentary was a new way to find form out of something deeply formless, and it has inspired him, he tells me, to create his first feature film.

Between this new direction with filmmaking, Williamstown, and his production business, how does Harris stay focused? He points to his zodiac sign (there’s a sense of fate in how Harris speaks about his past, present, and future). “I’m a double Gemini, so there’s a lot of juggling that happens both in my imagination and in my practice.” He also mentions his company BB2, which is an outlet for Harris’s production projects (with his production partner Josh Godfrey). But the documentary was a chance to present the purest part of his voice, one which is concerned with putting himself at the centre of the piece—the “diary play” format.

“In Yale, I started to literalise the idea of ‘one for them, one for you’.” His first diary play was called KMS (The Feels), which was about his college experience during the 2016 Trump election. In this play, you can read a young Harris’s reflection on his insecurities of wanting to be a playwright, but also feeling that he was killing off a part of himself that went out to nightclubs all the time. “I was in New Haven. I wanted to kill myself the entire time.”

At Yale, Harris stumbled on an existential question, one that he is constantly in the process of answering with his diary plays: who is he? And, then, what type of playwright does he want to be? Yale encourages students to make a production line of content for regional theaters. For Harris, this was antithetical to creativity. “A new one didn’t need to come every year. A play represented a very special inquiry that was bigger than myself and had to be put down on paper.”

In the playwriting programme, students were expected to come up with seven plays by the time they left. Slave Play,“Daddy”, and Harris’s other works have longer lifespans (I saw Slave Play in 2024), and with Slave Play. Not a Movie. A Play, they’re even being revisited with other mediums—Harris has ambitions to turn “Daddy” into a movie.

The documentary is treated like a diary play, and Harris places himself at the centre as a character and actor. “I don’t actually act much within it, though. I try to erode my ability to be self-conscious in a way that invites a performance in the documentation. I mean, we’re filming ourselves literally getting drunk.”

I, and most mainstream audiences, first encountered Harris as an actor in television cameos. In Gossip Girl, Emily in Paris, and What We Do in the Shadows, he portrays a version of his own loud and hyperactive personality. (He also advised on Euphoria and rewrote and produced on the miniseries Irma Vep.) Harris is traversing the television multiverse and inserting himself into various aspects of pop culture. And I think he does it for fun, not for any particular artistic reason.

There are serious, arthouse projects, too. Harris recently starred in Sean Price Williams’s The Sweet East (2023), and the week before we met, he was in Athens to work as an actor on Romain Gavras’s next project.

On his first memory of acting, he remembers the first time he was on stage. “I got struck by the act of being vulnerable with another person. I felt parts of my brain switch off. That’s one of the things I feel strongly about: it’s hard enough writing and being vulnerable on the page by myself at any hour of the day, with all the juggling I do. It’s infinitely harder to turn off the world and be submissive like an actor can.”

Active acting, he says—as in, being the leading man—will probably happen in his forties, once the groundwork has been laid for his business, and when he learns to be able to turn off the noise of the world. “I don’t think I can go act in a Christopher Nolan movie right now— I’ll miss 50 calls and that would be anxiety inducing.” When he has worked out his acting muscles, though, watch out, he says, with a typical, and enviable amount of self-belief.

“It’s gonna be fabulous.”

There’s a scene in the documentary that really sums up the double Gemini.

Speaking to his cast members, he explains how his inspiration is derived from storing an eclectic mix of references— film, music, art, etc.—and online worm-holes described as “internet tabs” that straddle pop culture and high art.

During our conversation—and sometimes from a digression—he waxes passionately on the works of Iranian director Reza Abdoh; how he “enjoys” rugby players on TikTok (he vehemently dislikes F1), the connotations of political social media posts, and how Lars von Trier’s film Dogville (2003) was the main reference for Slave Play, as well as being a major inspiration in general.

“I’m always emboldened by the ability to pull out a reference,” Harris says. “If I’m told I cannot do something, I can point to something Abdoh or [the late anime filmmaker] Satoshi Kon has done. Having a reference means less pressure to be an inventor. When you watch so many things, you realise you cannot be the first. And I love that.”

All references have equal merit, and Harris is famous for intellectualising pop culture in his own plays. Rihanna’s song ‘Work’ is used in the opening scene of Slave Play to profound effect. Whenever I hear it now, I associate the tune with his character Kaneisha.

He also recalls a recent conversation with the American video artist Arthur Jafa, who has worked with Beyoncé, on the limiting discourse around her use of samples: “[Critics] are always missing a point of what a sample can do. The beautiful thing about Black people sampling is that it is a form of remembering. In the canon, our work is eaten up, consumed, redistributed, repackaged, and the Black person who made it is thrown away, forgotten.” With sampling, Black Americans create a great annotated text of their history with new products, he explains. “That’s what I try to do with referencing. It’s my writer’s way of sampling something I don’t want forgotten.”

Then there is Melvin Van Peebles (1932–2021), the great American filmmaker, actor, musician and icon of Blaxploitation cinema. The groundbreaking Sweet Sweetback’s Baaadasssss Song (1971) was “sampled” in the monologue that caused his switch from acting to writing. “He is a great multi-hyphenate. A huge, huge inspiration.”

He traces his first interaction with Van Peebles to being a young boy on the internet, fascinated with independent cinema. “You can only watch Gaspar Noé or Claire Denis until you ask if Americans have ever made anything this interesting? And then you ask, have any of those directors been Black? Melvin Van Peebles comes up fast.” Discovering Van Peebles put Harris on this path to seeking other Black auteurs. And naturally, that brought him to William Greaves, the first Black filmmaker to put himself at the centre of an American documentary. “Greaves was fuelling my documentary,” he tells me. “And there’s the great Black subject in Portrait of Jason (1967), about Jason Holliday. So many of these things are a part of my foundation, from seeking a part of myself inside the canon,” he explains. “Where am I situated, as both a Black body, and a queer body?”

Harris’s desire to understand his place in the canon, and to insert himself as a permanent part of it, is central to everything he does. “Legacy is the most important thing to me.”

Harris wants to see the greatest minds of his generation succeed. The attention Slave Play awarded him was great at first, but then he began to feel an “ick” seeing how written-off his peers were for working in similar, abstract ways. He points to the gatekeepers.

“There are a lot of feckless leaders, people who will not commit to their mission: to continue supporting exciting young artists,” he says, genuinely bothered. “The great work of my generation might fall away for the most mediocre. That was one issue.”

The second issue was that playwrights are not natural at persuading theatres to take on their work, he says. “Slave Play happened because I’m such a salesman. I know how to sell myself and my work because I watched my mother do it in the salon. I mean, in “Daddy” there’s an infinity pool on stage. It wouldn’t have happened if I didn’t have that acumen.”

While Slave Play was on Broadway, Harris decided to help some of his friends on projects that were deemed “unsellable”. The first thing he took a crack at was a play from two people he “considers geniuses”: Patrick Foley and Michael Breslin, and Circle Jerk (2020).

“It was one of the first things I produced after a major theatre in New York refused to put it on their main stage.” A year later, he was proved right: Circle Jerk was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, and Harris got the itch to produce.

“I want to be someone who shines a light on the great writers of my generation,” he tells me. (Harris says “my generation” with the same communal meaning Allen Ginsberg did.) “I want my legacy to be like Jordan Tannahill or Will Arbery or Rianna Simons. People who can point back and say: ‘Jeremy was working his ass off and creating a bunch of stuff. But this play wouldn’t exist if Jeremy hadn’t taken a second look at it, or produced it’—that’s the kind of artist I want to be.”

Harris tells me that he is also driven by topping his own success. It’s possible that his work ethic comes from an enduring desire to stay a relevant part of the zeitgeist; to not be left behind. But he is also relentlessly ambitious, comparing his own progress with American playwright and director George C Wolfe’s. “I think, OK, he ran a theatre in his thirties. I need to get on it fast with producing.” Just when you think he has exhausted his long list of projects, he brings up another film which I hadn’t yet heard of. “This is a secret, but Peter Ohs, editor of the documentary and director of 2024’s Erupcja (a movie Harris made with him and Charli XCX) and I are going to premiering our film The True Beauty of Being Bitten by a Tick on the opening night at SXSW in March,” he says.

Harris sees the ongoing act of creation as similar to being a professional athlete: “In high school, I was going to the theatre, learning my lines like a sportsperson. I look at Serena Williams and how she changes as she gets older, building new muscles to stay ahead of her game. That’s what I’m doing.”

This constant mission for self-improvement and learning is assisted by surrounding himself with the most interesting artists, writers, and fashion leaders—and not just in New York, and not just for smaller productions. “I travel a lot. I do think that we live in too global a society to not want to connect with artists everywhere,” he explains, before telling me about a recent enviable trip to Tokyo, then hanging out with Gavras in London and Athens; text messaging Pakistani director Saim Sadiq (who directed the excellent Joyland in 2022), to also texting Levan Akin (of last year’s Crossing), who is visiting New York from Sweden, and who Harris wants to employ for one of the projects on his upcoming slate.

Not only is Harris a part of this generation’s who’s who of global creative artists, but he’s also taken on the Gertrude Stein style mission of bringing them all together, and becoming a de-facto chronicler and connector. “My partner [the Parisian producer Arvand Khosravi] asked me: ‘Do you go out to Cannes to collect international filmmakers like Pokémon cards?’ No. I’m just a fanboy,” says the magpie. “And I’m going to stalk these people until we meet for a drink.”

“Oh, wait. My agent is on the phone.” Harris, a man who can be forgiven for needing to get back to work, generously rejects the call, engaged in a thought about the Donald Trump victory. His next play, he explains, will be about the President-elect. “He’s experimental theatre, that’s what keeps him interesting.” No doubt Harris’s seething, satirical vision will get a reaction from Trump when it finally shows, but this is precisely what I suspect Harris wants.

His work will always be political, he admits. Harris’s Williamstown play, Spirit of the People, is about being an American, and being a part of a global class of privileged citizens that is “immensely critiquable”.

His ongoing success, and mainstream fame, has resulted in a never-ending series of invitations into rooms of power (many of which he accepts, and, as I mentioned at the start of this piece, where we first came into contact), and I ask how he squares that with his desire to be a revolutionary voice. At those glamorous dinner parties, with people whose politics are sometimes the reverse of his own, a few of the evenings have ended in screaming matches, he says.

“I’ve never abandoned who I am, or what my mouth is going to say.” And I believe him. Like the audience comfortably sat in the theatre, awaiting the curtain to open on a production of his, only to find themselves exhilirated and disturbed, those who come into contact with Harris in the social heights he operates in will find him unfiltered.

For Harris, being successful is a means to a more honourable outcome; having a voice powerful enough to stand up for people—whether it is through producing other people’s work, or in his own controversial, but engaging, writing. In the end, for Harris, it’s all about how we are remembered, even if it means confronting people with the very depths of your raw humanity, both the beautiful, the poetic, and the ugly. Through Harris’s work, it is all laid bare. “I don’t just write to write. It’s a response to a life lived,” he declares. “I’m more excited about leaving behind a collection of work that feels like it functions with the same heartbeat; the same, dyed-in-the-wool nastiness of someone who had something to say.”

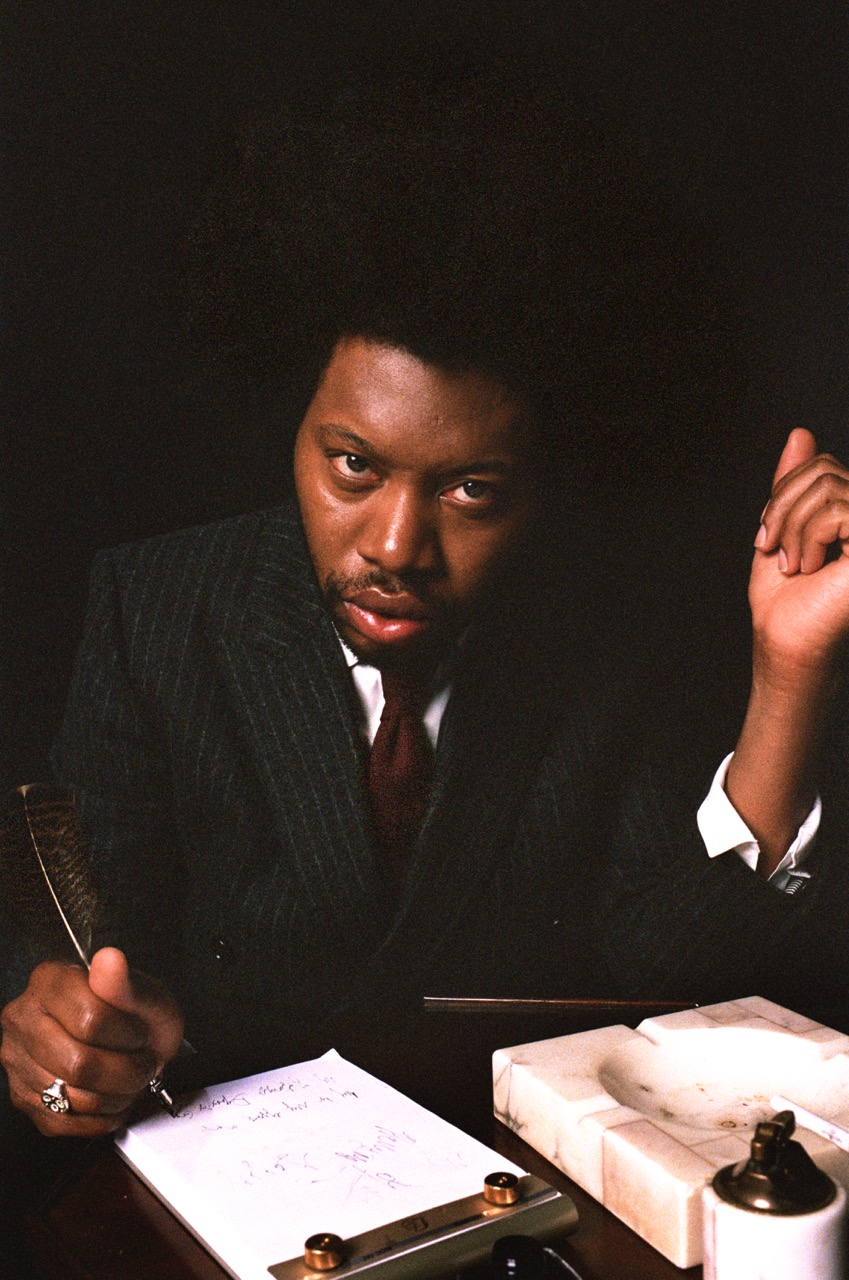

Credits

Creative direction by Fatima Khan

Photography by Max Montgomery

Production by Anna Pierce

Set Design by Milena Gorum

Videography by Mynxii White

Styling by Maurice Daillo

Grooming by Derrick Bernard

Outfit 1: Top by Celine. Shirt by Dior. Trousers by The Society Archive. Jewellery by Bernard James. Shoes by Prada.

Outfit 2: Jacket by Luar. Trousers by The Society Archive. Jewellery by Bernard James.

Outfit 3: Courtesy of Willy Chivaria. Shoes by Prada.

Foot Note

For our editorial shoot with Jeremy O Harris, we designed the desk and quill setting to evoke a sense of nostalgia and power. The quill, as the original instrument of written expression, represents the timeless art of storytelling. Shot on medium-format film by Max Montgomery, the vintage atmosphere of the set is balanced by the dynamic energy of New York’s streets, blending past and present. The word remains the most essential tool for any artist.