In 1989 the German artist Gerhard Richter made his first trip to the Upper Engadin valley, an area in the east of Switzerland, staying as a guest at the Hotel Waldhaus in Sils Maria. An area renowned for its beauty and the quality of its light (this is a part of the world the Romantic poets once dubbed “sublime”), Richter quickly fell in love, returning during both the winter and summer over the course of the next three decades.

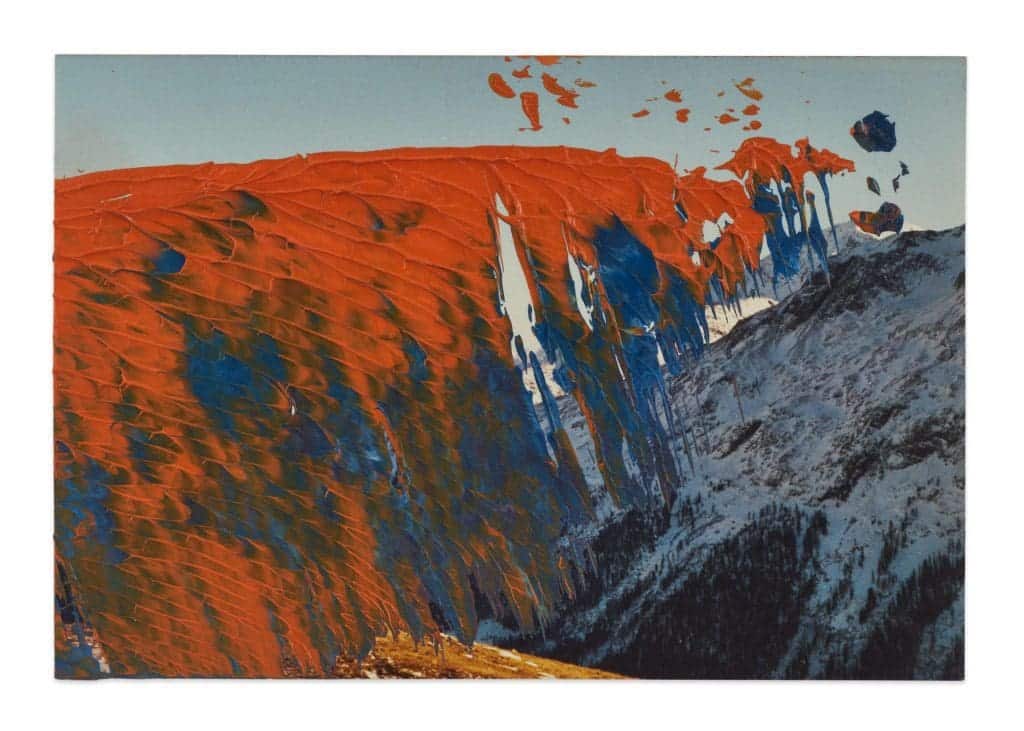

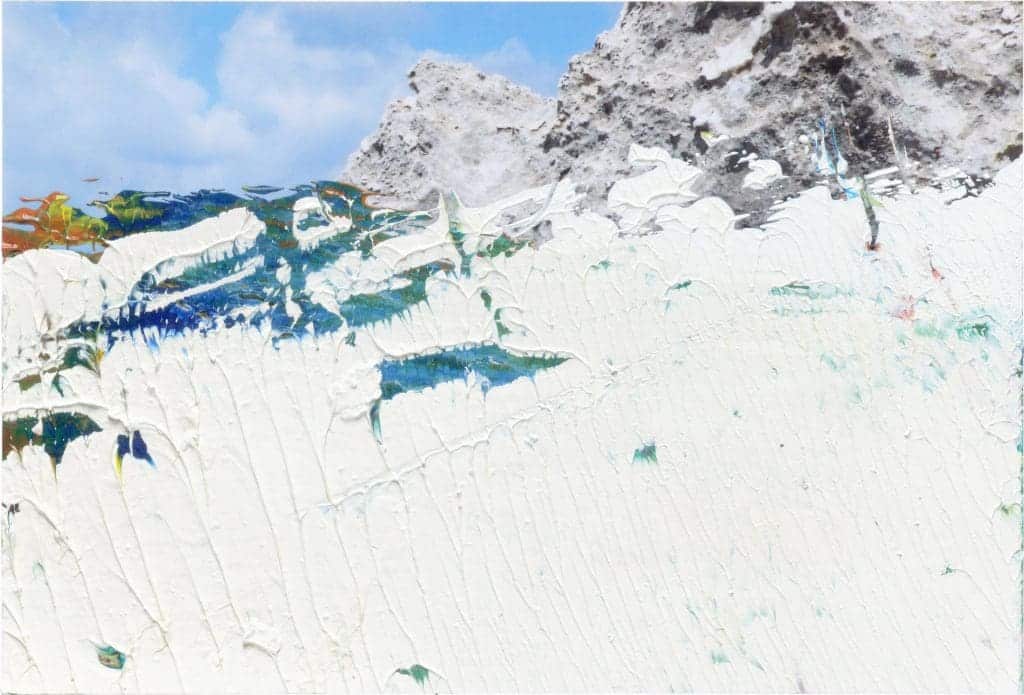

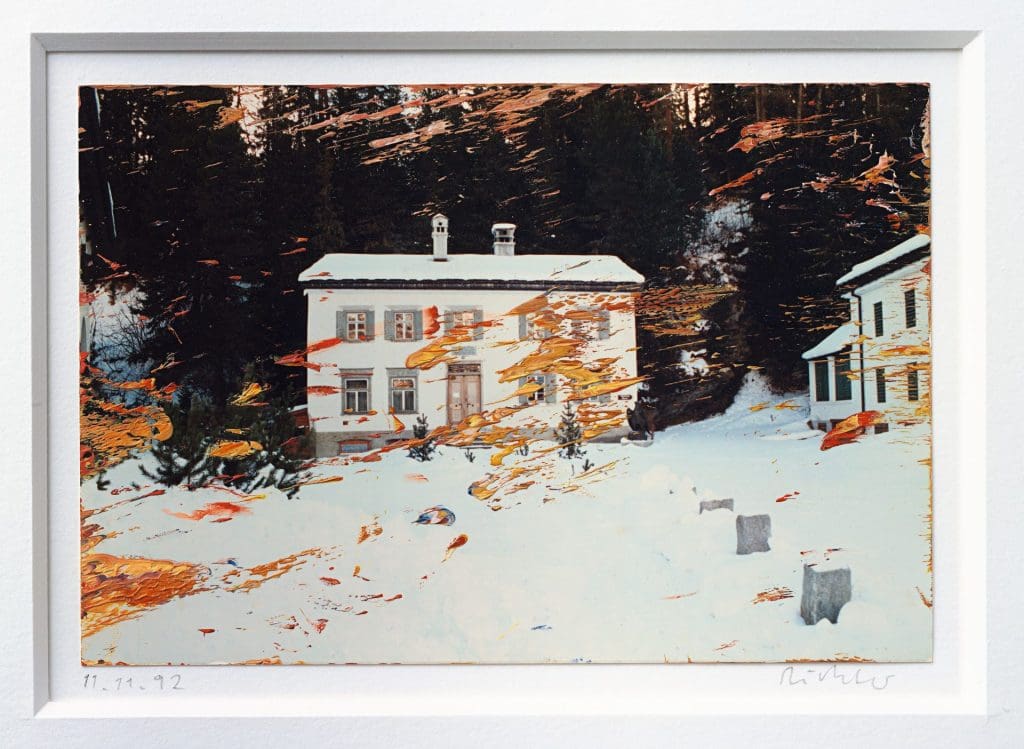

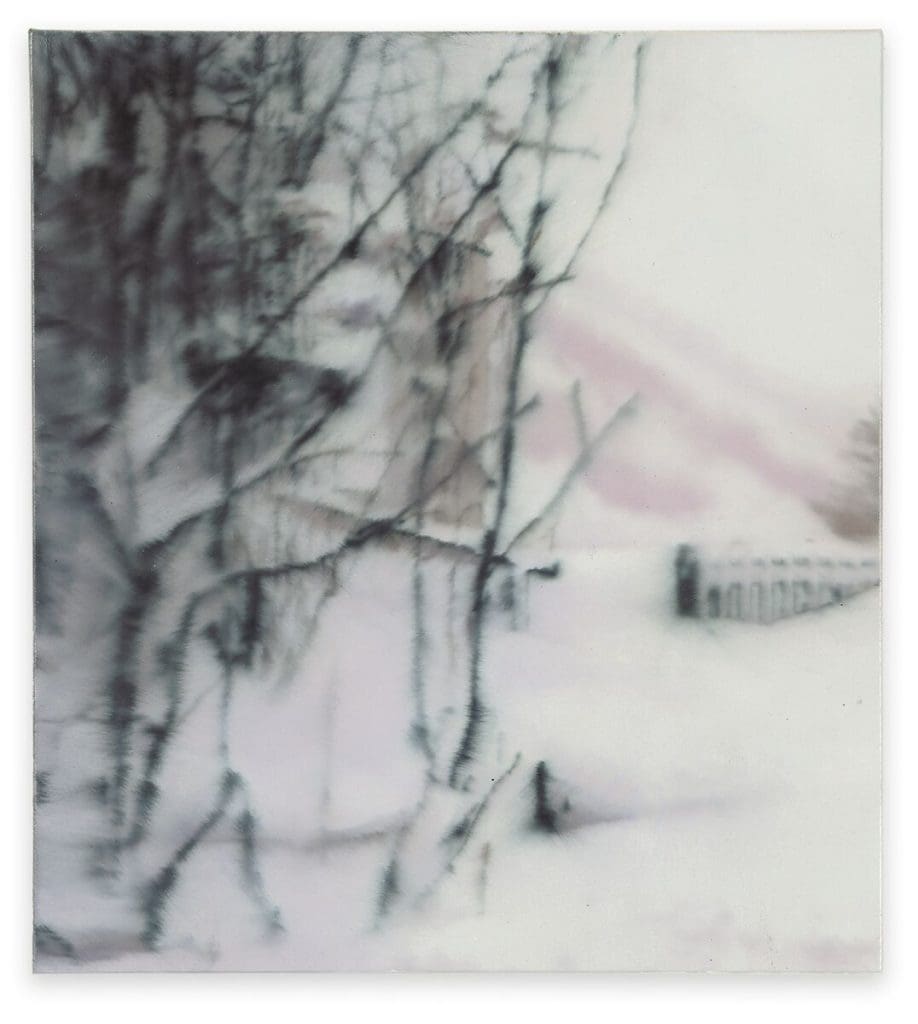

A three-part exhibition at Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz, which also encompasses the nearby Nietzsche-Haus and Segantini Museum, examines the many hundreds of works Richter created during these Alpine getaways. The vast majority start with photographs from his personal archive: relatively small, straightforward snapshots that he would take whilst walking and hiking. He would then work over the images with oil paint. An image of snowy trees is splattered with blue and white dots like snowflakes on a Christmas card. Swathes of primary colour tumble down the mountains like avalanches, or rise up into the sky like flames. The colours – which Richter often moves around the surface with a roller or a squeegee – are sometimes thick and marbled, creating patterns which rhyme with the geological and vegetative forms beneath.

Gerhard Richter, Piz Bernina, 1992 © Gerhard Richter 2023

Gerhard Richter, Val Fex, 1992 © Gerhard Richter 2023

As ever, Richter is interested in playing with our perception, with artistic interventions which make us ask ourselves what we are really looking at. (“Art should be like a holiday,” once wrote Paul Klee. “Something to give a man the opportunity to see things differently and to change his point of view.”) Richter would project many of his postcard-sized images onto canvases, allowing him to paint the scenes in a photorealistic manner. Richter would then brush across the painting before they had fully dried, creating a blurred effect. In St Moritz (1992), a crystalline image of mountains, trees and rooftops appears murky and illegible as if we were partially sighted: “strange and vaguely directionless,” writes the curator Dieter Schwarz in the exhibition catalogue.

Richter’s indeterminacy shows him grappling with the notion of the sublime. An affective response to something that is so beautiful it is terrifying; so enlightening and unknowable, for Richter the blur is the sublime’s most accurate expression. Richter also created 11 metal sphere sculptures – three of which are presented in each of the exhibition’s three locations. With a matt, reflective surface, they become “a synonym for the sublime and inaccessible appearance of nature,” as writes Schwarz. The engulfing atmospheres of Wasserfall (1997) and Ravine (1997) also symbolise the haze of memory; the Proustian prick of a place once visited.

Gerhard Richter, 11.11.92, 1992 © Gerhard Richter 2023

Gerhard Richter, Schnee (Snow), 1999 © Gerhard Richter 2023

For Richter, who is now 91 and retired from creating art, this exhibition also has mnemonic potential, looking back at a life lived in art. Vitrines of his photographs show the archive fever possessed by the artist, as well as his meticulous process of capturing and editing. Many photographs (displayed, as was the case in the early digital era, with a timestamp) are only painted many years later. The exhibition also pays tribute to the 1992 exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist at Nietzsche-Haus where he first presented his Engadin works. This has followed up for the first time 30 years later with 39 works displayed at the Nietzsche-Haus which also sit in the company of Richter’s stained glass window.

A 20-minute walk up the hill from Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz, Richter’s work is also put in dialogue with that of Giovanni Segantini at his museum. Unlike Richter, Segantini’s paintings of the Engadin, made over a hundred years earlier, are pastoral – more straightforwardly figurative than Richter’s postmodernist interpretations. Unlike Richter, Segantini was not a holidaymaker. He lived and died in the Alps –literally – falling ill with a stomach infection as he worked on a triptych on the Schafberg mountain. Yet the two artists nonetheless constellate. In the museum’s rotunda, three panoramic paintings by Segantini – each in different seasons, are met in the middle by Richter’s metal sphere. Blurring the works on display, this ball won’t tell any fortunes. But there is one illuminating detail. In La Vita (1898) a moon is reflected in a pool of water, mirroring Richter’s own sphere. This heavenly body is a constant, continuing always in its orbit.

‘Gerhard Richter: Engadin’, curated by Dieter Schwarz, is on view at Nietzsche-Haus, Segantini Museum and Hauser & Wirth St. Moritz from 16 December 2023 until 13 April 2024. The show will be accompanied by a catalogue by Hauser & Wirth Publishers produced in collaboration with Nietzsche-Haus and the Segantini Museum and featuring an essay from Dieter Schwarz.

Main image: Gerhard Richter, Val Fex, 1992, Oil on colour photograph

© Gerhard Richter 2023