Think of the Riviera and images of sunbathers and palm trees spring to mind. But the French Riviera had a curious start before becoming the byword for coastal luxury and lifestyle, writes Maxime Toscan du Plantier.

Ask a French person about the French Riviera and you’ll likely be met with momentary confusion before tentative recognition dawns: “Ah, you mean the Côte d’Azur?” What English speakers know as the French Riviera—the sun-drenched Mediterranean coastline where billionaires anchor their yachts and celebrities try to avoid paparazzi—draws on the Italian name for a coastline (riviera) while we French use the more literary metaphor of the “blue coast” to refer to roughly the same place. How can we account for these different names? As often, history offers a rich explanation for such linguistic peculiarities. The facts are that the English started speaking about the Riviera in the 1840s, 40 years before the first mention of the Côte d’Azur in French. And so one of France’s most famous and touristic regions is a recent invention—and not a French one.

If the Riviera had to be invented, it is because the joys we associate with it—basking in the summer sun or bathing in a clear, turquoise sea—are not universal experiences everyone always longed for. In fact, French historian Alain Corbin documented how Europeans before 1750 primarily perceived the sea as a source of fear. A remnant of the biblical Deluge, the sea was a reminder of the wrath of God and a looming threat to humanity.

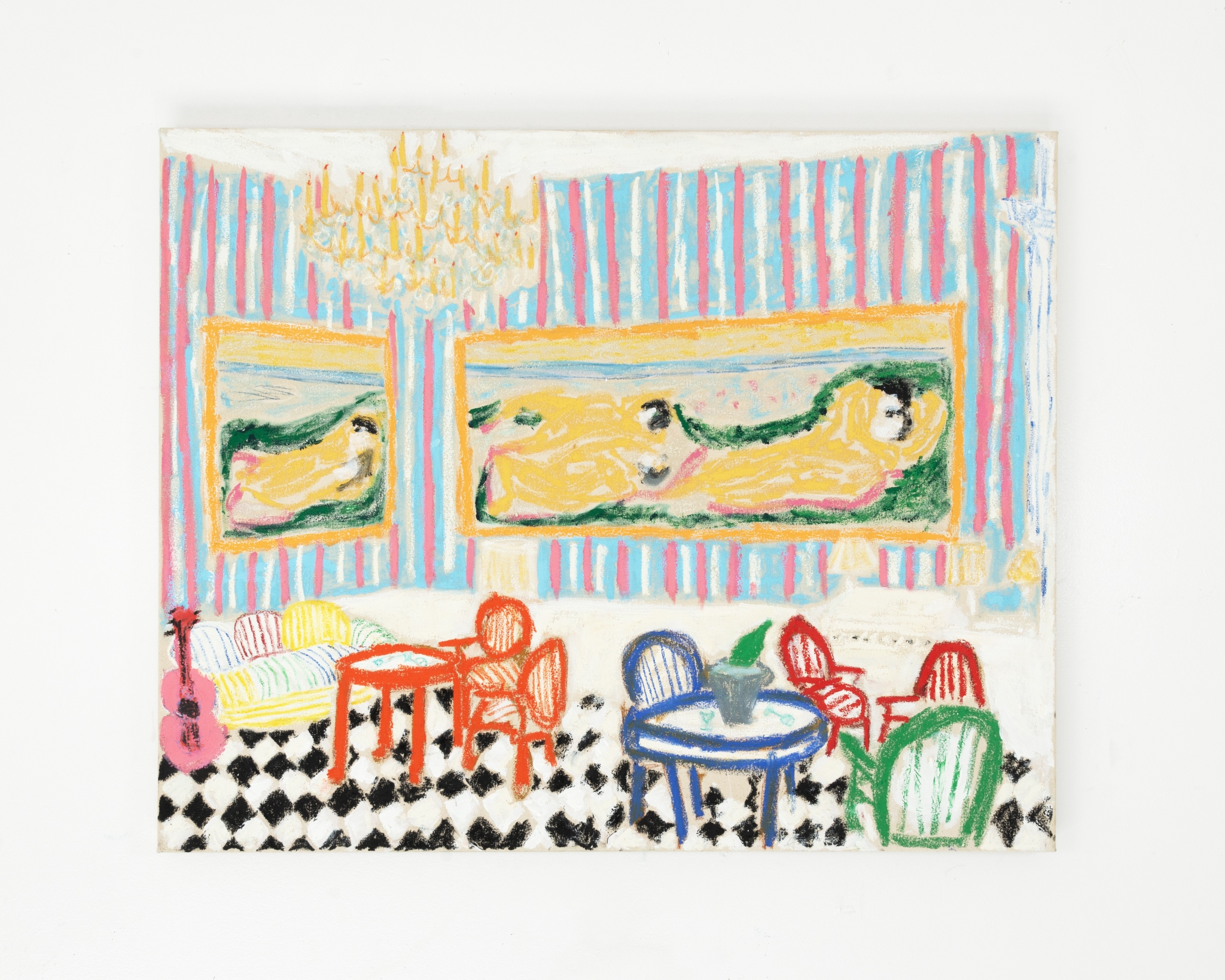

Artwork courtesy of Michael McGregor.

Beyond the metaphor, the shores embodied a more immediate sense of fear and danger. The fortified walls of Antibes or the watch towers dotting the Corsican and Amalfi coasts—which now overlook yachts and cruise ships, and populate Instagram stories— are a silent reminder of an era when the Mediterranean held threats of invasion and attacks. Although most Mediterranean piracy died down in the late 17th century, it haunted Europeans’ imagination long after that. The open sea inspired awe, not desire.

Travel itself was a grave activity, laden with tangible dangers. The concept of travelling for pleasure would have seemed absurd to most Europeans: those who travelled were either merchants risking their lives for good money or pilgrims embracing the danger as part of their spiritual journey.

But attitudes change. The 1763 Treaty of Paris put an end to a protracted war between Britain and France, allowing for safer journeys in Western Europe. This opportunity birthed a new species of traveller: the young English aristocrat, freshly graduated from Oxford or Cambridge, undertaking his Grand Tour, a year-long educational journey through Europe. Accompanied by tutors and servants, the Grand Tourists, as they came to be called, visited Paris, Florence, and Rome or the newly discovered Pompeii. Despite giving its enduring name to this new activity, the English tourists cannot be credited for creating the phenomenon that would transform the Mediterranean coast into the cultural landmark it is today. For that, we must look to an unlikely source: the British medical profession.

Travel itself was a grave activity, laden with tangible dangers. The concept of travelling for pleasure would have seemed absurd to most Europeans: those who travelled were either merchants risking their lives for good money or pilgrims embracing the danger as part of their spiritual journey.

Maxime Toscan Du Plantier

Artwork courtesy of Michael McGregor.

The radical transformation of the Mediterranean from threatening to therapeutic began with British doctors. Throughout the 18th century, they wrote about the medical virtues of water (hydrotherapy), and cold water baths (balneotherapy). In 1752, Richard Russell, an English doctor concerned with the curative powers of water, transformed the well-established spa practice. In his Dissertation on the Use of Sea Water in the Affections of the Glands (1769), he described seawater as being medically superior to the spring water of spa towns. Under his influence, the city of Brighton quickly transformed into a fashionable resort for health-conscious British aristocrats.

Between 1780 and 1830, as England’s industrial revolution triggered unprecedented urban growth, medical concerns shifted. In a country where the population had doubled, “consumption” or “phthisis”—tuberculosis— became a seasonal epidemic and one of the century’s major causes of death. Physicians blamed the disease, or at least the worsening of its symptoms, on the climates of England’s industrial cities and started looking for better weather conditions.

Scottish surgeon and travel writer Tobias Smollett described in his 1766 book Travels through France and Italy how his consumption was cured by the climate of the South. His meticulous weather records from an 18-month stay in Nice lent scientific authority to his account. By the late 18th century, Nice was filled with members of the British aristocracy and of the royal family seeking a remedy for their complaints.

Geopolitical changes facilitated this new international mobility: Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 ushered in a new phase of relative stability in Western Europe and France’s conquest of Algiers in 1830 was hailed in French and English newspapers as putting an end to “African piracy” in the Mediterranean—a threat, historian Gillian Weiss remarks, which existed more in the Europeans’ imagination than in reality.

Artwork courtesy of Michael McGregor.

And so, from the 1800s onwards, the annual migration was quite established: November through April saw thousands of English families from the landed gentry, accompanied by doctors and servants, journeying to the Mediterranean shores of France and Italy in search of health. To name this health resort, they borrowed the vernacular name that had been given to the coast of the Italian Republic of Genoa, the “Riviera”. The Riviera was born, not as a place of leisure but as a prescription.

In the 1870s, the pages of the prestigious British Medical Journal routinely featured correspondence from British doctors reporting on the favourable weather in Nice or Cannes, and how “many serious cases have been greatly benefited by the climate since their arrival” in what they called the “French health resorts”. The English started shaping their winter resorts according to their needs and tastes. They brought architects to build grand villas and purpose-built accommodations whose names announced the intended clientele: Hôtel des Anglais, or Hôtel d’Angleterre. These establishments combined a de rigueur luxury with health and bathing amenities. Even the urban planning was made to reflect English priorities, with an emphasis on parks and open space where they could enjoy the virtues of “fresh air”. The most iconic of these health infrastructures is Nice’s Promenade des Anglais, which was designed and funded by the local Anglican church and its clergyman, Lewis Way, in the 1820s on the model of English seaside piers. The promenade inspired the building of Cannes’ Croisette in the 1850s and 1860s.

Cannes offers perhaps the most striking example of the English shaping the Riviera. Lord Henry Brougham is credited in local lore—which he originated—with “discovering” the city in the winter of 1834, when a cholera epidemic prevented his planned journey to the Italian Riviera. Supposedly enchanted with the modest town’s climate and landscape, he had Villa Éléonore-Louise built in 1836, named after his tuberculosis-stricken daughter. Historian and local archivist Alain Bottaro documented how, in the next 30 years of his life, Brougham shaped the city of Cannes into what it is today, involving himself in local planning and securing the city’s water supply. He set the trend for other English aristocrats or entrepreneurs, including Thomas R. Woolfield, who developed what became known as the “English neighbourhood” (quartier anglais). Woolfield’s gardener, John Taylor, established in Cannes what was maybe the first real estate agency in the world, in 1864. These English gardeners even transformed the region’s botanical identity by introducing palm trees, which art historian Kenneth E. Silver called “the classic botanical symbol of the French Riviera”, creating an imported emblem for what was, in essence, an imported paradise.

In addition to the English, the Riviera began receiving French and Russians aristocrats, and, from the 1860s, the French upper-middle class. Among them were artists and authors, who would popularise the Riviera in French culture under another name. Stéphen Liégeard published his book La Côte d’Azur in 1887, giving the region, which had already featured in Guy de Maupassant’s 1885 best-selling novel Bel-Ami, its current French name. The bright colours of the Riviera also attracted painters Albert Marquet and Armand Guillaumin who, alongside Henri Matisse, initiated Fauvism in 1905, with their paintings of the Saint-Raphaël region. Their paintings would in turn inspire the aesthetic of the Riviera’s advertising posters.

Artwork courtesy of Michael McGregor.

After first sending the English to the Mediterranean shores in the winter, medicine would now transform the Riviera into the summer playground we are now so familiar with. In the 1910s, European doctors discovered a new therapeutic darling: the sun itself. They named their innovation heliotherapy, an extension of the earlier balneotherapy. Patients with tuberculosis— and soon, nearly everyone—were prescribed sun-baths in Switzerland’s sanatoriums or on the Riviera’s shores. This transformation was almost immediately reflected in literature. Zelda Fitzgerald’s Save Me the Waltz (1932) and her husband F Scott Fitzgerald’s Tender Is the Night (1934) were both set in the Riviera’s hot summer sun. The latter opens with a passage that explicitly chronicles this revolution: “On the pleasant shore of the French Riviera, about half way between Marseilles and the Italian border, stands a large, proud, rose-colored hotel. Deferential palms cool its flushed façade, and before it stretches a short dazzling beach. Lately it has become a summer resort of notable and fashionable people; a decade ago it was almost deserted after its English clientele went north in April.”

F Scott Fitzgerald’s description of the thinly disguised Hotel du Cap-Eden-Roc captured how dramatically the seasonal rhythm of the Riviera had been reversed. He had first-hand account of this reversal, having himself sojourned there in the 1920s alongside Picasso and Hemingway in the circle of Gerald and Sara Murphy, a couple of wealthy Americans expatriated on the Riviera after the war, and who convinced the hotel to stay open for the summer of 1923. French historian Pascal Ory described how this medical novelty and seasonal reversal is behind a revolution in European culture and beauty standards in the 1920s. Since medieval times, aristocratic standards of beauty had been defined by pallor. A tanned skin marked one as a peasant or a labourer, someone who had to toil under the sun rather than enjoying an indoor life. The wealthy advertised and maintained their status by preserving the paleness of their complexion, protecting themselves from the sun and using white face powder. In the mid-1920s however, these centuries-old beauty standards were suddenly inverted: as industrial labour was driving the working class away from the fields to the factories, the mines, or the offices, pallor lost its uncontested appeal. Beauty magazines documented this radical shift with excitement and uncertainty. During the summer of 1928, Vogue devoted a feature to the season’s most pressing question: “Whether or not to sunburn themselves is a question that many women are asking themselves and their beauty specialist, as they leave town to depart for lands of warm skies, to lie on beaches underneath an unaccustomed summer sun.” But by July 1929, Vogue declared that “now the entire feminine world is sunburn conscious!”: tanning had triumphed. The new adepts of sunbathing developed their own rituals and accessories. Photos from Jacques-Henri Lartigue from the summer of 1932 show scenes of a surprising modernity, with women stretched out on the sand on specifically designed mats, with glasses and vinyl record players. With the season inversion, the Riviera emerged as the summer headquarters for European high society. The Monaco Grand Prix, first held in April 1929 became an essential event on the social calendar. Though World War II briefly interrupted this summer sociability, it returned with renewed glamour in the post-war years, immortalised in Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief (1955), where jewel thieves prey on sun-bronzed aristocrats on the shores of Monte-Carlo, Nice, and Cannes.

Artwork courtesy of Michael McGregor.

The Riviera’s exclusive character found its cultural apotheosis in the Cannes Film Festival. Film scholar Dorota Ostrowska notes that they form a perfect symbiosis. Cannes was selected in 1939 precisely for its elite infrastructures—grand hotels, railway connections, and airport access— developed to accommodate Europe’s aristocracy and, for two decades afterward, the festival deliberately cultivated this rarefied atmosphere of the Riviera. It fashioned itself as a natural extension of the coast’s privileged heritage, with movie stars playing the role previously held by royal families and aristocrats.

By the late 1950s, however, the social landscape started shifting. French workers had obtained two weeks of annual paid leave through the massive strikes of 1936 under the Popular Front government, and a third in 1956. The democratisation of leisure it allowed gradually transformed the Côte d’Azur, as middle-class and working-class families claimed their spot on formerly exclusive shores. Later French classics such as Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou (1965), Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969), and comedy classic Le Gendarme de Saint- Tropez (1964), starring Louis de Funès, captured this more layered and sociologically diverse identity of the Riviera.

The Riviera’s successive metamorphoses chart the entire history of modern tourism, from winter sanctuary for the sick to summer playground where international jet-setters and middle-class French families share adjacent stretches of the same golden coastline. More remarkably, this evolution became a template that would be exported and replicated across continents—a cultural blueprint with remarkable staying power. As geographer Jean-Christophe Gay documents, by the late 19th century, European aristocrats who had wintered among the palms and pines of Nice and Cannes began deliberately transplanting this model to their home territories. The Habsburg monarchy transformed Slovenia’s and Croatia’s Adriatic coast into the Austrian Riviera, with Opatija crowned as the “Austrian Nice”. Across the Atlantic, Florida’s first developers explicitly marketed Palm Beach as “the American Riviera” in the 1890s, importing French-trained architects to ensure authenticity in their Mediterranean fantasy.

Since then, Rivieras have proliferated with remarkable abandon—Devon’s English Riviera, Mexico’s Riviera Maya, Bodrum’s Turkish Riviera, Santa Barbara’s California Riviera— many coined by marketers seeking to bottle and sell this particular blend of exclusivity and leisure. Its newest iteration, the Mexican Riviera, stringing together cities along Mexico’s Pacific coast, exists only as a cruise line invention, a collection of ports unified by nothing but brochures.

Artwork courtesy of Michael McGregor.

What makes the Riviera concept so powerful is precisely its placelessness. It embodies what anthropologist Marc Augé terms a “non-place”: airports, shopping malls, and all-inclusive resorts, environments designed to welcome (some) visitors while ensuring no one truly belongs. This peculiar atmosphere permeates in HBO’s The White Lotus. In the first season, the resort manager played by Murray Bartlett, encapsulates Augé’s concept when he tells employees to “create for the guests an overall impression of vagueness” and to be “more generic.” This institutional ethos of erasure is palpable throughout the seasons, with quasi-interchangeable luxury resorts in Hawaii, Italy, and Thailand, where location merely influences menu items and activities while the fundamental experience—designed placelessness—remains unchanged. This same placeless quality appears in US President Donald Trump’s proposal to rebuild Gaza as a “Riviera”, presumably modelled on his beloved Palm Beach, as a resort concept disconnected of historical and cultural context, and emptied from its inhabitants.

A Riviera, then, is fundamentally a place one visits but never calls home, which explains why the French themselves rarely use the term. The landscape that launched countless imitations remains the Côte d’Azur to the French—a geographically unique coastline which is both a beacon of French culture and the very real home of actual inhabitants, not merely a concept to be franchised around the globe.