On a grey, wet day, Natasha A Fraser visited Dame Judi Dench at her bucolic home, a mini Stratford-upon-Avon where the theatre legend held court and spoke about her career on both the boards and screen.

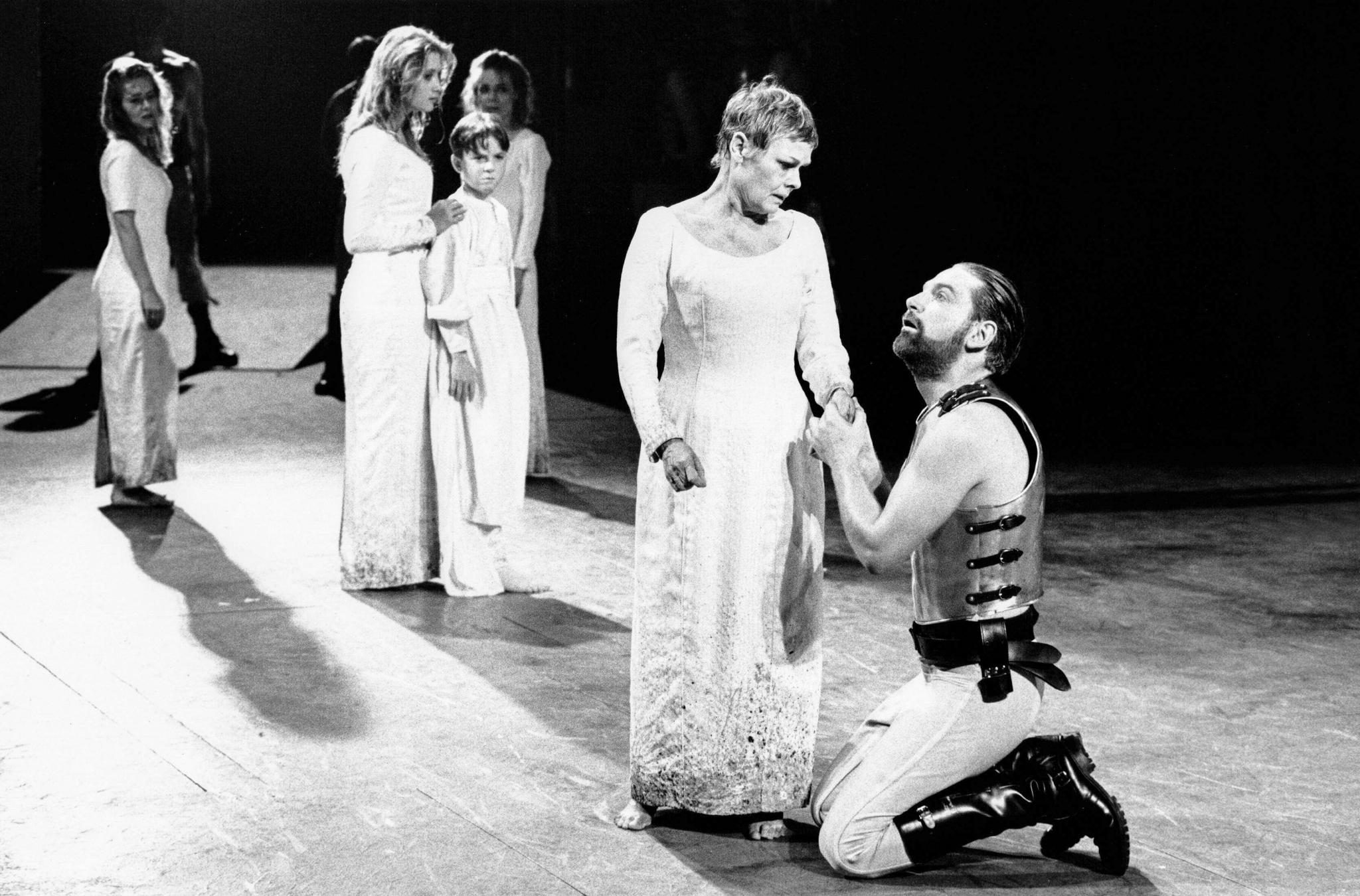

Hours before meeting Dame Judi Dench, I fear that the foul weather will turn into a freak storm and my train to Surrey will stop mid-journey. My recurring nightmare is an audience with an icon that doesn’t happen. Ralph Fiennes’ words haunt: “Judi Dench inhabits any text by Shakespeare with an immediacy, a truth, an understanding that is natural, intelligent, and unique,” he writes. Dench is also a Companion of Honour, a royally appointed award for outstanding achievement. The build-up to my increasing anxiety becomes three-fold. It stems from my respect for an incomparable female force in theatre, television, and then film. There’s also the fact that Dench is universally admired in a profound way: not a single mean word to be heard. And on an emotional level, just as I was raised with the late Queen Elizabeth II, I was also brought up with the 90-year-old Dame Judi Dench, charting her career from Trevor Nunn’s productions at the Royal Shakespeare company to all that followed.

Suiting an actor celebrated for playing queens, Judi Dench has created a whimsical and leafy kingdom. Lying outside of London and spread over five acres, it consists of a 17th-century yeoman’s cottage, a former coffin maker’s workshop, an armillary sphere, a pond rife with ducks, manicured box hedges, a thicket of brambles, and different trees planted in memory of friends that range from Sir John Gielgud to Franco Zeffirelli to Natasha Richardson. “There are hundreds,” Dench later tells me. Far from morbid, the trees are a testament to her enchanted life—“Sometimes I talk to them.”

Walking towards Dench’s front door, a fluttering name tag catches my eye. “Maggie Smith” is written on greyish black slate. Attached to a crab apple tree, it is Dench’s latest. I feel a pinch of sadness until seeing her front doormat. “I’ve been expecting you Mr. Bond,” it reads. Her role as M in eight James Bond movies became a game-changer, making her into an international household name. In 1995, at the age of 60, Dench turned into a major movie star for her role as M in GoldenEye. “Two more frightened people, you can’t imagine,” Dench says referring to herself and Pierce Brosnan. Then, she went on to win an Academy Award for Shakespeare in Love (1999), and has since stacked up seven Oscar nominations, the latest being for Belfast (2022).

While researching Dench, everyone I spoke with mentioned her high spirits, intelligence and humour, but not her presence. When she silently appears in front of me, there’s an otherworldliness. Though famous for James Bond, I think of another franchise, Star Wars. I can picture Dench beaming in and out like Sir Alec Guinness. George Lucas, you missed your chance.

Her 1680 home is wood-beamed with low-slung ceilings and diamond-shaped casement windows. Cosy, it is packed with memorabilia of theatrical productions, bric-a-brac from trips around the world, a variety of teddies and hearts signalling her two collections among countless framed photographs of her late actor husband Michael ‘Mikey’ Williams (1935 – 2001), her actress daughter Finty Williams, and grandson Sammy Williams who made her into a TikTok sensation during Covid. “Mind your head,” the diminutive Dench warns as we walk into her light-filled study. Dressed casually in a swathe of layered tops and loose trousers, her choice of colours—a mix of beige, ivories, and whites—enhance her inner glow.

Though her face is untouched, “I wouldn’t mind getting rid of some of the wrinkles,” she says. Her mercurial nature, feline features, bone structure and elfin haircut have allowed agelessness. Dench looks fabulous. It must be satisfying for someone who was once told by a film producer, “Miss Dench, you have everything wrong with your face.” But the young Judi Dench, who caught attention with her Ophelia, Titania, Juliet, and Viola, and became reputed for her work at the Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company, never cared about Hollywood. “I was in the happiest place of my life, which is in the theatre,” the thespian says. Dame Penelope Wilton—another brilliant talent— points out that the theatre is collaborative. “You depend on each other and you work as a team,” she says. “The play is the thing, not the individual performance. So that discipline stays with you forever. That is why, in whatever medium, Judi is such a joy to work with, and why all her performances are so alive. She has total concentration in the moment.”

According to Robert Fox, the theatrical titan and film producer of Iris (2001) and Notes on a Scandal (2006), Dench is blessed with “an extraordinary temperament—calm and non-egotistical.” Referring to her as “a properly top person” he describes her “democratic attitude” as setting the tone of the film set. “Incredibly supportive to younger actors, she is not rushing off to her trailer, surrounded by assistants,” he notes.

During the filming of Notes on a Scandal, the director Richard Eyre recalls Dench “chuckling at the idea of filming outside a rather esoteric massage parlour called Fettered Pleasures, or racing down the Kentish Town Road at two o’clock in the morning, at the wheel of an ancient VW Golf with a look on her face of wild exhilaration and just a little bit of fear.” In Eyre’s opinion, “that look exemplifies all her acting: a passionate commitment to everything she does and a desire always to attempt something that she thinks she might not be able to achieve.”

At the New York premiere, the actress Lauren Bacall berated Eyre—a theatrical giant—for forcing Dench to lie in a hot bath, sweating profusely, smoking a cigarette. “She didn’t believe me when I told her it was Judi’s favourite scene,” he says. And that is key to Dench, who always wanted to take risks and loathes being referred to as Britain’s great national treasure. “I sound like some old rock, locked in a cupboard that nobody wants to dust,” she tells me.

Hardly. Dench’s book with Brendan O’Hea, Shakespeare: The Man who Pays the Rent (2024) is a bestseller, while her show I Remember It Well, in conversation with Gyles Brandreth, was a sell-out at the Royal Albert Hall and most recently York’s Royal Opera house (October 2024). In her ninth decade, Dench might be termed a white-haired phenomenon, a one-person brand associated with excellence, wit and the most recognisable voice in the world. “A Clover butter ad bought this house,” she informs me.

Nevertheless, her child-like naivety, and wonder”—as described by Penelope Wilton —hit home when a family of magpies lands on her lawn. “Hello, hello, hello Mr Magpie, how are you and how’s your wife?” Dench begins, keen to ward off their bad omen reputation. It becomes quite an eccentric scene, as equally superstitious, I am frantically saluting them with my left hand. “When’s your birthday?” she asks, sounding intense. “I have rarely met someone who does that apart from my own family.” Though I firmly and respectfully view her as Dame Judi, we bond—but then who doesn’t bond with someone who agrees to a tattoo at the age of 81? “It says Carpe Diem,” she says. “You know: seize the day? But I heard on the radio that it’s savour the day, which is much nicer.” There’s also her cockney parrot called Sweetheart who sounds like Sid James (from the Carry On films) and is partial to saying “slag”, “slut”, and “Boris Johnson”—(“Not from me,” she says about the latter.)

When playing opposite Maggie Smith in David Hare’s The Breath of Life (2002), Dench let off steam by taking rides in a crane and being sped around Trafalgar Square on a motorbike. Small wonder that Peter Hall (1930–2017), the late theatrical legend, described her as a dangerous actor and “that’s not as easy as it sounds”. In his shortlist of female greats, it was Edith Evans (1888–1976), Peggy Ashcroft (1907–1991), and Dench. Michael Billington, the Guardian’s theatrical critic, however, is reminded of Ellen Terry (1847–1928), who described acting as “imagination first and observation afterwards”. “Judi Dench embodies that to perfection,” he says. “I would make no distinction between her work in classics and contemporary plays: in both, she displays an imagination that allows her to respond directly to an author’s text.” Billington also highlights Dench’s “capacity to switch in a moment from gaiety to sadness and to catch what Virgil called the ‘lacrimae rerum’ or ‘the tears in mortal things’.”

Most actors revel in compliments, but Dench looks uneasy hearing Billington’s praise. “My imagination is sparked by others,” she begins while her beringed hands nervously cover her mouth. “I think it’s the writing and what you have to deal with.” Still, when pressed on her modus operandi, Dench refers to her inner camera. “I’ve said to every young actor, you must have a camera here,” she says, pointing to her forehead. “Just so that you can record things, because the more you understand about the condition on everything and everybody, it becomes a truth that you can recall. All experiences can be turned into a plus.” Nevertheless—and this is essential—her inner camera is backed up by flawless technique. “The Central School gave me my voice,” she reveals. Her London-based drama school also taught her to breathe properly and project her voice in order “to be heard in the back seat at the upper circle”.

Indeed, if the ever-contemporary Dench has a pet peeve, it’s the growing tendency of actors “micing up” in the theatre. “DON’T,” she dramatically declares, a reminder that she has also played Lady Bracknell both on the stage and screen. “I am going to go straight through a hole in the roof. They [the National Theatre] started that after Anthony and Cleopatra in 1987. The problem is that the mic means you don’t have to try as hard… I do wonder if the theatre will survive.” I suggest that the stage’s technical sound has infinitely improved and we need to adapt, particularly due to the rise of film and TV stars in the theatre. “Yes, we do have to adapt,” she concludes. “But you might as well stay in and listen to the radio.”

Dench is not alone in thinking this. And I wonder about my late stepfather, Harold Pinter (1930–2008). A trained actor who performed in repertory, he was nicknamed the “awesome baritone” by fellow playwright Arthur Miller. Surely the intimacy of Pinter’s first hit play, The Caretaker (1960), would have been ruined if the original cast of Alan Bates, Robert Shaw, and Donald Pleasence were mic’d up? I then recall Dench in his short play A Kind of Alaska (1982), part of Other Places that premiered at the National’s Cottesloe theatre. It was over 40 years ago but I can still hear her—particularly the delivery of Deborah’s monologue. I also think back to Dench’s Adriana in The Comedy of Errors (1976) at Stratford and as Barbara Jackson in Pack of Lies (1983) that left the awesome baritone, and his brood, speechless. For the theatre to make a lasting impact, the voice is everything. It allows sexuality, it allows humour.

And I have to further agree with Sir Peter Hall, who first directed Dench in the ground-breaking production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Stratford 1962), that “God gave her the most astonishing voice”. When she says “How dare they?” it defines regal while her single pronunciation of “heaven” sounds celestial: an up-there experience. During our encounter, Dench uses the word four times. A recent return to her childhood home near York is “heaven”. Being cast as Volumnia, Kenneth Branagh’s mother in Coriolanus at Chichester (1992) is “heaven”, Johnny Depp is “heaven” during their carriage scene in Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (2011). “I’ll show you the earring that he bit off,” she says with mischief. And listening to all her daughter’s audio tapes is termed as “heaven”.

“Though I firmly and respectfully view her as Dame Judi, we bond—but then who doesn’t bond with someone who agrees to a tattoo at the age of 81? ‘It says Carpe Diem,” she says. “You know: seize the day? But I heard on the radio that it’s savour the day, which is much nicer.’”

“Though I firmly and respectfully view her as Dame Judi, we bond—but then who doesn’t bond with someone who agrees to a tattoo at the age of 81? ‘It says Carpe Diem,” she says. “You know: seize the day? But I heard on the radio that it’s savour the day, which is much nicer.’”

Natasha A. Fraser on Dame Judi Dench

Due to suffering from age-related macular degeneration, Dench is practically blind. “My ma had it too,” she reveals. “I don’t know when it started. Perhaps I refused to let it rule my life? But now I can’t read at all, it’s pathetic.” Obviously, I argue otherwise. “Well, it is pathetic,” she insists. “But it could be worse, I suppose.” Presumably she draws solace from her Quaker faith. “You hear the silence drop,” Dench says, when describing the Quaker meetings. “And shared silence is as important as shared laughter “ (At her 90th birthday bash last December, Dench handled her condition with aplomb. When friends came up and introduced themselves, she would say, “Of course, it is.”)

“There is no drama,” says Robert Fox. Instead, there’s continued laughter. “For goodness sake, get the froth off,” Dench insists, adamant that laughter “gets the froth off the top, otherwise you won’t get to the proper drink.” She remains amused that Robin Williams curtseyed when she won her best supporting Oscar in 1999 for her role as Queen Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love, and she thoroughly enjoyed working with the comedian Billy Connolly in Mrs Brown (1997). Initially, they met when seated on horses. “Billy said, ‘Is that you under there?’” she says, imitating Connolly’s Glaswegian brogue. Smitten by his personality, she freely admits, “If Billy said I had size 8 feet, I’d say ‘yes’.” And there’s Dench’s own element of surprise—her jumping up then imitating the late Donald Sinden as Malvolio is totally unexpected. So is her admission that, “as a child, I wasn’t good in a cinema… I think Mr Disney set out to frighten you and make you cry,” she opines. “When Bambi’s mother is killed… when Dumbo’s mother is in a cage and he’s outside. I mean they never stopped, did they?”

Nor do I want to stop with Dench. Before our conversation ends, I ask about her collection of rings, a tangle of chain chokers and clanky silver bangles. “Isn’t it terrible? I wear them everyday,” she says. (Actually, Dench could get away with sporting a large safety pin in her nose.) As she recalls the memories linked to each item, it’s her wedding ring inscription that resounds the most: “You have bereft me of all words, my lady,” it says. The line comes from The Merchant of Venice, Dench’s least favourite Shakespeare play. “It’s an arse paralyzer,” she almost shrieks. “I mean who behaves well?” Nevertheless, the poetic phrase is fitting for Britain’s favourite Faerie Queene.