“Perhaps I love it too much.” Christian Petzold on trying and failing to adapt George Simenon’s novel ‘The Snow Was Dirty’ (1948) three times. And why he will try again a fourth time.

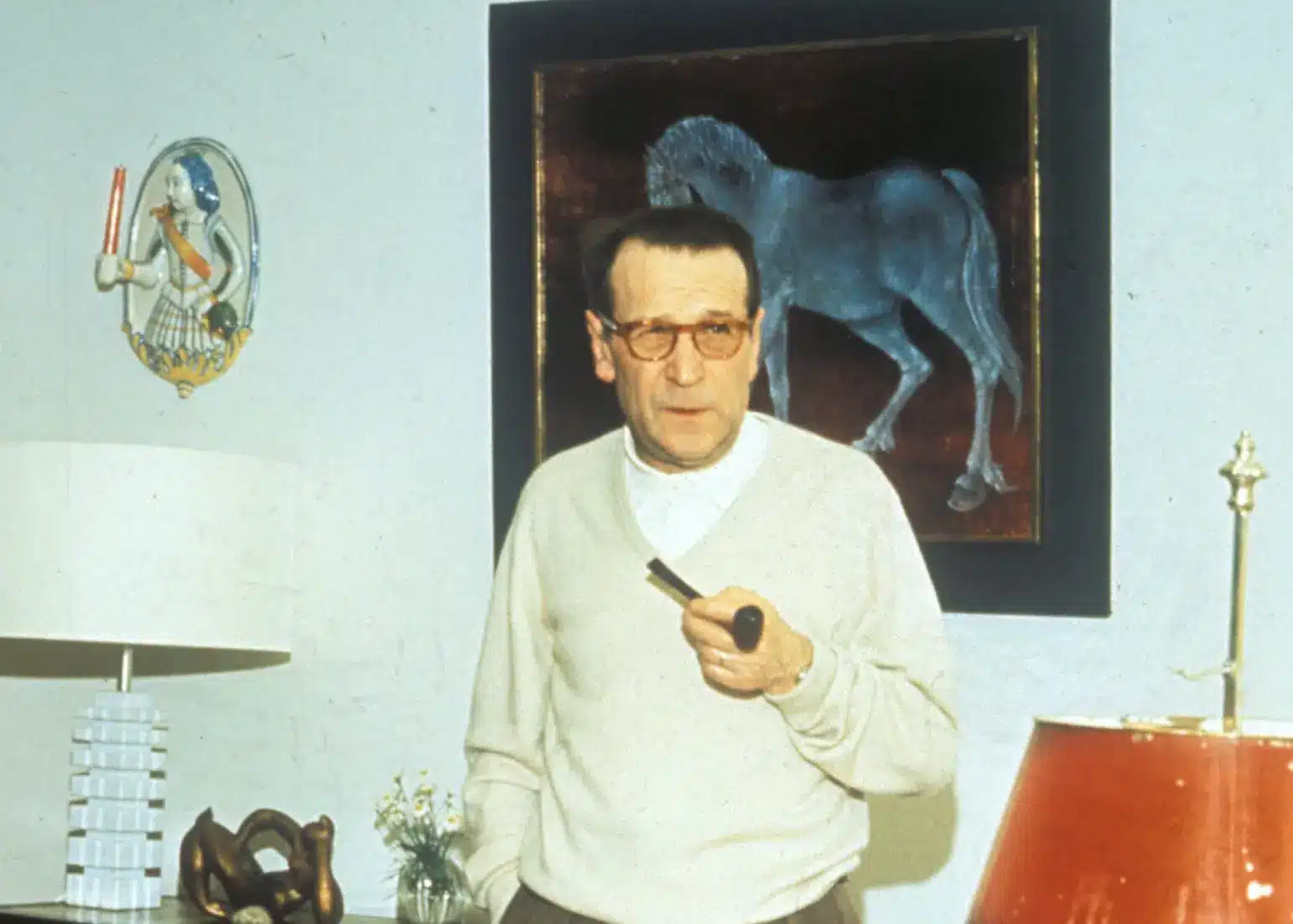

It is always refreshing to hear one master filmmaker praising the work of another, unprompted. A week after seeing it at the cinema, the German director Christian Petzold is still chewing over the bones of Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023). “It really is a masterpiece,” Petzold tells me on a video call from his home in Berlin. “You can smell Auschwitz, you can see the smoke from the crematoria, you can hear the noise, but not once are you ever inside the concentration camp.”

It is easy to see why Glazer’s rigorous formalism might appeal to Petzold. Both filmmakers like to take a novel and put their own stamp on it. The Zone of Interest takes its basic premise from Martin Amis’s 2014 novel of the same name, but in Glazer’s adaptation the narrative becomes something altogether stranger and more disturbing. Petzold also has history in this department: two of the 63-year-old German director’s best films, Phoenix(2014) and Transit (2018), are sinuous adaptations of World War II-themed novels.

For the former, Petzold and his long-time writing partner Harun Farocki transplanted French author Hubert Monteilhet’s 1961 novel Return from the Ashes and its story of a returning concentration camp survivor from post- war Paris to post-war Berlin. The latter was an even bolder experiment, as Petzold took the German author Anna Seghers’s 1944 novel Transit and set it in the present while maintaining its persecutory themes of the past.

But sometimes even a screenwriter of Petzold’s prodigious talent can come unstuck. Five years ago he bought the film rights to the Belgian author Georges Simenon’s novel The Snow Was Dirty (1948). Since then, Petzold has tried three times to adapt it for the screen without success. “This is one of my favourite novels so perhaps I love it too much,” Petzold says. “I always start crying when I reread it because it’s so intelligent. But after 15 or 20 pages of writing I always stop, which must be a sign that it is not possible. However, I will try a fourth time, I promise.”

In spite of these false starts, Simenon’s 1948 novel about a cold- blooded teenage killer and pimp on the loose in an unidentifiable occupied European city had already left an indelible mark on Petzold’s work as a filmmaker. With his career still in its infancy, he and his wife travelled to California in 1997 to see his old friend Farocki, who was then teaching a film course at Berkeley university. The two men set to work on their first screenplay together, which resulted in Petzold’s big screen directorial debut The State I Am In (2000). It was Farocki who handed Petzold a copy of The Snow Was Dirty as inspiration for their screenplay about a wayward teenager who betrays her parents—former members of a left-wing terrorist group who have gone underground.

“Harun gave me Simenon’s book to read because its story contained similar themes about the betrayal of those who are good, decent, and

to whom one wants to belong,” Petzold says. “The young man without a moral compass in The Snow Was Dirty believes himself excluded from the world of decent people, which offends him, and that’s why he betrays and destroys those around him.”

Simenon’s novel had been inspired by the Belgian writer’s experience of World War II and living in France during the German occupation. Though Simenon is best known for his Inspector Maigret novels about the adventures of a lugubrious Belgian detective, he also wrote a series of hard-bitten crime novels, including The Snow Was Dirty, that he dubbed his “romans noirs” for their dark, uncompromising themes. In an interview, he described them as being about “the naked man, the one who looks at himself in the mirror while shaving and has no illusions about himself.”

Petzold likens Simenon to a profiler for the uncanny way that “he puts himself in the shoes of a murderer.” The Belgian’s working-class roots and his depiction of working-class characters, notably in The Snow Was Dirty, also appealed to Petzold, whose father was often without employment after his parents emigrated from East to West Germany in the 1950s. “When I think of Simenon, I think of him buying a houseboat at the end of the 1920s and travelling along the canals of Belgium because he wanted to reach the towns and cities from the rear,” Petzold says. “He finds his position in the outlying districts, not by gravitating towards the centre of a city where the libraries and the universities are.”

When Petzold first considered adapting The Snow Was Dirty for the screen he looked at setting it in Ukraine, and travelled to the VUFKU film studios in Odessa a couple of years before Russia invaded the country in February 2022. He also visited parts of Crimea, which had already been annexed by Russia in 2014. “I twice stayed in parts of Ukraine under Russian occupation and these parts of the country were dead,” Petzold says. “The brutal reality of these experiences shocked me so much that I did not want to make the movie anymore. Perhaps the feeling will come back but I don’t know.”

Another obstacle in the way of adapting Simenon’s novel is that Petzold often feels too close to the material for comfort. The loneliness of the book’s thuggish protagonist, Frank Friedmaeir, haunts Petzold, who grew up in the town of Haan feeling a similar sense of dislocation and isolation. “I think my problem with this Simenon novel is that the main character of this young man who kills people also has a desire for a normal life and to live in a country without occupation and disturbing morality,” Petzold says. “Yet in the same breath he destroys everything around him because he feels dirty like the snow. This is all a little bit too close to me.”

When Petzold and Farocki were working together on the screenplay of The State I Am In there was a similar moment when autobiography and fiction began to collide. “I had a problem because the main character was a boy who, together with his parents, is part of the underground,” Petzold says. “It was only when I changed the boy into a female character that I felt comfortable working on the script.” It is a process of distancing that can be found in many of Petzold’s films, such as Phoenix (2014), Barbara (2012), and Undine (2020), which all feature strong female protagonists.

But when Petzold attempted for a second time to write a screenplay based on The Snow Was Dirty from the perspective of a young girl, Sissy, whose love for him Frank cruelly betrays, it did not work out. “I changed everything so as to write it from Sissy’s point of view,” Petzold says. “But immediately you know everything about what is right and what is wrong so that you lose all the ambivalence of Simenon’s story.” One can only wonder whether Petzold’s screenwriting mentor Farocki, who died in 2014 at the age of 70, might have helped his friend find a way out of this dilemma.

This is not so certain. The more Petzold rereads The Snow Was Dirty and other “romans durs” by Simenon, the more he is becoming convinced that they are not suited for the screen. “There was a tradition started by Gustave Flaubert’s novel Madame Bovary that continues with Chekhov and Simenon where the storyteller is not single but ubiquitous,” Petzold says. “It is as if we are inside the writer’s brain and imagination. When I read Simenon I can smell, touch, see, and hear everything that he writes. It is as if the protagonists at the moment of their downfall become truly sensual. That doesn’t work in the cinema where you can just show how people run, feel, hide, and look.”

But life for such a compulsive creator as Petzold must go on, with or without The Snow Was Dirty. This spring the German director will begin filming his latest screenplay, which has the title Miroirs No. 3 and is named after French composer Maurice Ravel’s five-movement suite for solo piano. It tells the story of Emily, a young piano student from Berlin, who is involved in a car accident in which her friend is killed. She is taken in by a family who initially make her feel comfortable and support her recovery. That is, until they don’t any more. “Emily begins to wonder who these people really are and what dark secrets they hide,” Petzold says. How very Simenon-esque it all sounds.