What does it take to have a sense of smell so magnificent it attracts the attention of Yves Saint Laurent? At his atelier in Marrakech, William Hosie speaks to the botanist and perfumer Abderrazzak Benchaâbane.

“I think a fragrance is rather like a diamond,” says Abderrazzak Benchaâbane, crown prince of perfumiers and former gardener to Yves Saint Laurent. It’s late July in Marrakech and the perfume-maker greets me with a radiant smile, sitting comfortably in his vast living room with walls the shade of desert sand. Standing out against these tones is his fez-blue polo shirt, dampened here and there from the heat of the North African summer. “You can tell I’m in Morocco,” he laughs.

Benchaâbane is known for creating perfumes that are lavish and entirely unique. Each bottle is different. Not because each bottle contains its own unique formula, but because the formula itself is derived from ingredients that are, themselves, fickle. “They contain so many multitudes—so many declensions,” Benchaâbane says. The rose, for instance, “varies in scent from one year to the next depending on whether that year was drier or wetter.” His shop is akin to a laboratory, and Benchaâbane takes a scientific approach to his role. A botanist by trade and a one-time student of chemistry, his fragrances are alchemical, his understanding of flowers granular.

His shop, Benchaâbane Parfumeur, is on the other side of the Jardin Majorelle from the Villa Oasis, which Saint Laurent bought in 1980 with his partner, Pierre Bergé. Jacques Majorelle, a French orientalist who created the eponymous garden in 1922, designed it as a rare blend of Muslim and Western influences, and brought over plants from all four corners of the world. Majorelle had, Benchaâbane says, a “compas dans l’oeil”—a French expression referring to someone’s ability to measure distances without resorting to tools. “I took the same approach,” Benchaâbane says, when he was brought on to restore the garden in 1998.

It had, by then, fallen into disrepair. Majorelle died in 1962 (“a garden without men becomes a wasteland,” Benchaâbane says), and the rarefied spot in which he lived—a lush and wealthy enclave just outside the hustle and bustle of the Medina—was at risk of being bulldozed by real estate developers. That was until Saint Laurent and Bergé rescued it, and entrusted Benchaâbane, by then already a local legend, with the task of returning the estate to its former glory. “I was given carte blanche. Moroccan gardens were always designed to be oases, with fountains, and ponds, and tall trees to create shade.” He redesigned the space just so, using archival photographs of the gardens in their heyday and sourcing the same plants from far and wide that Majorelle had, identifying them via invoices and records of thefts from the 1930s.

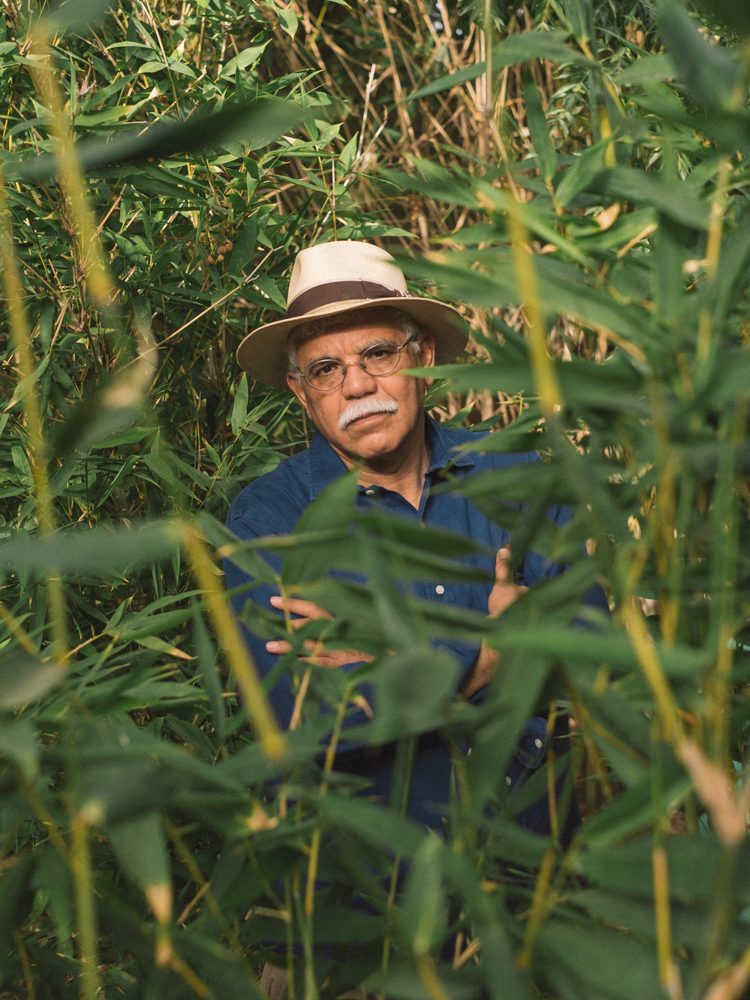

Abderrazzak Benchaâbane by Rida Tabit

Saint Laurent had a knack for sniffing out talent and asked Benchaâbane to create a fragrance based on Majorelle. “You like women, nature, and perfumes,” Benchaâbane remembers him saying. Those were the only directives given. “He was a very quiet man,” Benchaâbane says of the French fashion icon. “When I replied that he was the perfumier and I was just the gardener, he gave me a stern look which I took to mean, ‘There is only one step between the garden and the perfume bottle.’ And that step was mine to take.”

Rather than mining inspiration in the plants of Majorelle (many of them cacti and devoid of olfactory allure), Benchaâbane looked to something more abstract: the garden’s history as a melting pot of cultures. He wanted the scent to be a marriage of ingredients, as well as deeply, singularly ‘Marrakech’. “There’s a dessert mothers make here: l’orange à la cannelle [the cinnamon orange],” he tells me. By melding orange flower—supple, soft, unctuous—and cinnamon—spicy, pungent, earthy—Benchaâbane created not only a bestseller for the Saint Laurent gift shop (the designer worked with architect Bill Willis to transform the original painting studio of the Villa Oasis into a Berber museum), but also a timeless evocation of Moroccan childhood.

Benchaâbane was himself a child when he first learned the wisdom of plants from his mother, who is now 96. She comes from a family of Berbers, whose ancestral command of medicinal herbs shaped Moroccan custom over centuries. “My mother was a herbalist,” Benchaâbane explains. “She never had to go to the drugstore because there was nothing a plant couldn’t cure, whether burned as incense or boiled into tea.”

She lived a charmed life, he says, raised in a family that was part of Marrakech’s middle class. But his own life has also been shaped by a more rustic heritage: his father’s. Summers were spent with his family in the florid fields of the North African countryside, where the Benchaâbanes settled in the late 18th century. “We’d go to my uncle’s farm where there were Damas roses, and the women in my family would pick and distil them,” he says of these formative years.

Saint Laurent had a knack for sniffing out talent and asked Benchaâbane to create a fragrance based on Majorelle. “You like women, nature, and perfumes,” Benchaâbane remembers him saying. Those were the only directives given.

As is natural for a professional nose, the perfumier is keen to linger on scent’s ability to inspire reminiscence. “My earliest memory is of the orange flower,” he says, “which my mother would distil in springtime to obtain its water, which has healing as well as olfactory properties.” His nose is akin to a composer’s ear, able to detect the slightest inflections in any perfume. A rose can be “sweet” but it can also be “spicy” or “citrusy”. It thus tells the story of the place where it was made—and of its people. The orange flower, for instance, is now ubiquitous among the perfume bottles of Morocco, but originates from Andalusia; a reminder of the kingdom’s imperial inheritance from the time of the 11th century Almoravid dynasty, which stretched all the way from the Sahara to the Pyrenees.

By nature both symbolic and synesthetic, scent’s ability to conjure personal and cultural hinterlands has inspired many writers (notably Marcel Proust) and, to some degree, shaped the culture in which we live; even if that just means Marilyn Monroe name-checking Chanel No. 5 in Some Like It Hot (1959). In Morocco, though, fragrance is more than just a product or a symbol of glamour. It is the by-product of an art de vivre in which nothing goes to waste: every flower or fruit is mined for juice, tincture, medicine, and perfume. Benchaâbane’s scents are, more than luxurious creations, a metonym of the Moroccan lifestyle.

Indeed, Benchaâbane adds, the story of his country’s community spirit can be told through the story of its flowers. “When I cultivate and distil the orange flower,” he says, “I do so for everyone. For staff, family, and friends. It becomes a product around which we meet and share.” When an earthquake hit the Atlas Mountains in September 2023, the community was quicker to respond than the authorities. Moroccan solidarity, Benchaâbane says, is “legendary”. That is what his perfumes are really all about.

Continue reading: A film lover’s guide to fragrance