Cinema has the ability to teleport us to faraway places—revealing other peoples’ lives, and ask us to imagine ourselves among their landscapes and cities. Wim Wenders’ films have always been portals to these foreign places and ideas. Even after five decades as a director, his latest work Perfect Days is ‘made to measure’ for Japan, he tells A RABBIT’S FOOT. At the same time, there are other journeys he embarks on that are more internal: the frontiers of an artist’s mind, as seen in his documentary on Anselm Kiefer, following similar works about Pina Bausch and Ozu. For Wenders, understanding artists is as much of an adventure as visiting the American deserts he spent his earlier years travelling to. In this discussion, Wim Wenders tells Chris Cotonou about his beginnings, and how they would inform a prolific career as a filmmaker, the origins of New German Cinema, and why his work has always been informed by a sense of urgency.

You continue to be prolific. This year at Cannes you showed us the feature Perfect Days and the documentary Anselm (on artist Anselm Kiefer). I’d like to know what journey you are on at this stage of your career, as it still feels you have much to say.

Maybe it’s because I’m older. As a younger man, there seemed to be an infinite amount of movies in me—or so I thought—and that it could go on forever. Eventually I realized I didn’t have all that much time anymore. Movies take years of your life. (Anselm took three years, Perfect Days was very fast and only took half a year.) When I got into my seventies, I understood that I couldn’t make all that many anymore. The ones that I’d do would necessarily exclude others. So, I realized I had to be careful with my time. If I’m doing something, I need to be sure that it’s worth being one of the last things I might do. I’m more careful about choosing subjects now. They’d better matter.

Do you feel a sense of urgency, then?

Urgency is the word. I felt it in front of Anselm’s work when I visited his huge art space in the South of France, in 2019. It was a privilege that I could be in that landscape and wander around on my own. It would be great to let people share that experience, that place and that wonder! Perfect Days had its starting point with a similar urgency, and it was also a place that triggered it. I had wanted to return to Tokyo for so long, but during the pandemic no tourists were allowed. So, when I was invited on a work visa to look at these twelve tiny architectural masterpieces—toilets, sure, but temples to a basic human need—just to see if these places would inspire me in some way—maybe for a photo book, maybe a short film—I did not hesitate. It just so happened that I arrived in Tokyo when its population came back after a very long lockdown: Witnessing how they savoured that return and at the same time cherished and protected their public spaces, that was quite a revelation. It was so different from the experiences in my own town of Berlin, where parks and public places were practically ruined by that return to normal life. A sense for the common good was one of the huge commodities of the pandemic over here in Europe, but not so in Japan. So, I decided to write a script around these fantastic toilets and that (almost utopian) notion of the common good as perceived by Japanese culture.

You’ve made films all around the world. In the US, in Tokyo [with Tokyo-Ga] but I want to know whether the journey in each film, the plot, requires the particular geography. Did it need to be Japan to tell the story of Perfect Days, or could you take the plot of Paris, Texas and make it elsewhere?

For me, I can only tell a story if I feel it necessarily belongs somewhere. If I could just as well tell it anywhere else, I’d be lost. I need a relationship between story and place—then my brain works, then I know where to place my camera. If someone else would choose my sets and locations, I would arrive and not know what to do there. Perfect Days had to be in Tokyo. The film was ‘made-to-measure’.

I remember you saying that Paris, Texas was America through a European lens. Are you conscious that when you make a film about another country, your European voice transcends the journey—say in Japan?

My eyes are those of a ‘hopeless German romantic’, I cannot get rid of them. Then again, I love to go to other places, know other ideas, rules, ways of life. I’m totally dedicated to making sense of it all. Sure, if I film anywhere, it’s through the eyes of that German romantic, but when they see something that ignites their curiosity, then the essence of my work begins: I have to make sure that in the process of translating from one culture to another it’s not my vision that survives, but what aroused my interest in the first place. In these two cases here, it’s Kiefer’s art or Japanese culture that I want to present to people’s mind and allow them to absorb these subjects into their own cosmos. It’s not my idea of them that I want them to see, it’s the things themselves. I have an obligation towards the spirit of Kiefer’s art just as well as towards the ethics of that toilet cleaner in Japan. I have to live up to my subject, not bring them down to my opinion of them. My filmmaking has always been exactly that process.

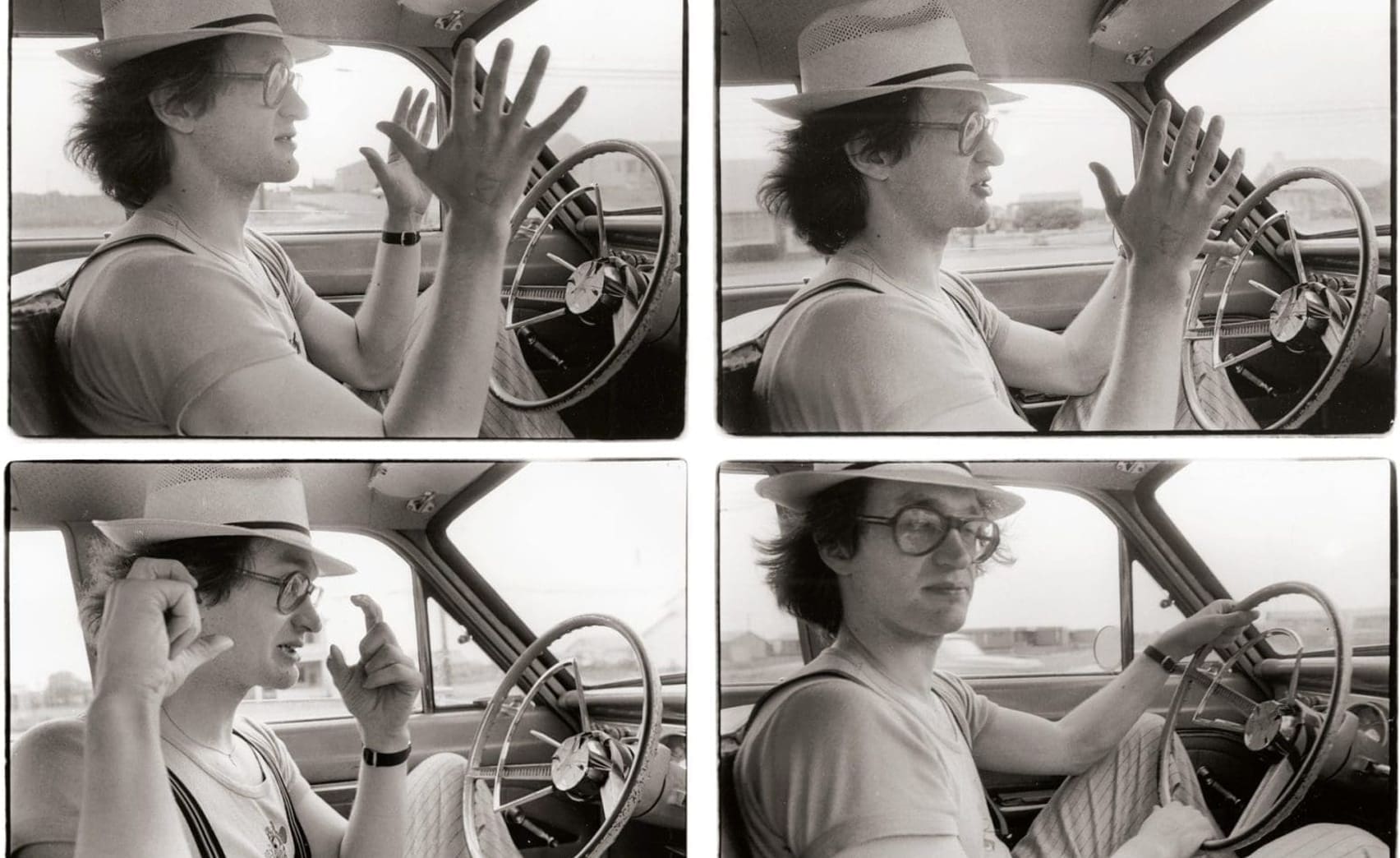

Harry Dean Stanton and Dean Stockwell.

ON AMERICA

I was watching your ‘Road Trilogy’ recently, and there’s a lot of American iconography, pop-culture that you translate to German culture. Clearly America influenced you a lot as a young man, but where did that emerge from?

The first music I really connected to came out of jukeboxes. The music my mum was listening to on the radio was German pop, while my father was interested in classical music, I didn’t like either. But eventually, I discovered Radio Luxembourg. The same American music I knew from jukeboxes and fairgrounds was playing here! I loved it. It was mine, and I discovered it for myself. I was also a big fan of comic strips, too, but the German ones were miserable. Donald Duck and Marvel were a better way to invest my pocket money. So, Rock ‘n’ Roll, blues, and comics were important cultural discoveries. None of them were German. So what? It was better than what people fed me with at home.

What I knew of my home town was ruins. Eighty-five-perfect of Dusseldorf was destroyed by the war. But through photographs and photographs, I knew there were fantastic cities in America! Big cars, amazing skyscrapers, incredibly beautiful women in bathing suits. The first movies I saw were Westerns, and I was mostly taken by the landscapes. So much horizon! So I slowly adopted a different culture as ‘my own’ that pleased me more. Everything about America seemed better.

There’s a great line in Kings of the Road. One of the characters says, “The Yankees have colonized our subconscious.”

[Laughs] I regret adding that line of dialogue that went in on the spur of the moment. At least now, it seems a bit too much ‘on the money’. But there’s a grain of truth in it. My subconscious was colonized by American culture. When I finally went to America, I was the first of any of my friends or family who got there. At first sight, it seemed as beautiful as I expected, but it wasn’t holding up well…

America didn’t match up to the idea?

The idea was too good to be true. Or better: it had been true once, probably, but wasn’t anymore..

Later on in your career, it seems you depart from these American symbols and codes. Do you feel like American culture doesn’t colonise the subconscious like it did?

I lived in America for fifteen years, and I saw that the American Dream—all these great ideas of liberty and a free world—had started to pervert into propaganda. It wasn’t like that when I grew up. As a boy, I didn’t know all that much about the devastations that had happened in Germany previously, as no one wanted to talk about it—but I was aware there was something wrong. The Americans had fought to liberate my country, I knew that. So, they were the heroes of my youth, because they had done the right thing. That was part of why I so much fell in love with American culture.

Today you could argue the US doesn’t have that moral innocence.

It’s a totally different ballgame today. Their morality has become a hollow language, they can repeat it as much as they want. They perverted their very own ideas, for example with the War in Iraq; they betrayed the ideas that founded the country, and that they really believed in at one time—and certainly I believed in them. Eventually, they disappeared. The America I dreamed of as a boy was gone.

You took many now-published photographs of America, on road trips and while shooting films. Do you see those photographs differently now, because of how your perception of the country has changed?

I felt that my imagery of America, taken in preparation of Paris, Texas or Don’t Come Knocking, for instance, was always “looking for America”. Some of the photographs, like from the book Written in the West, are still of the America I thought was pure and almost innocent. But I also witnessed a lot of decay. In the film Land of Plenty I confronted that loss of innocence explicitly.

Was this around the same time you were travelling with Annie Leibovitz? You could hardly have better company.

That was much later. I hadn’t made a film in America when I was travelling with Annie in ‘73. Sure, I was hoping I could shoot there, which I eventually did. I had just made my first couple of movies in Europe, and at that time I travelled a bit along the West Coast with Annie. Then, I felt, some of that proverbial ‘Land of Plenty’ was still visible. But you could also see it vanish. I’m a photographer of places, and landscapes give great accounts of civilization. The American West is also a graveyard of great ideas, a cemetery of the American Dream.

Whenever I discover a city for the first time, one of my first efforts is to find a cemetery. Nowhere else in a foreign place you can find out so much about its culture. It is the ultimate revelatory step to understand where you are, how people think, what their relationship is to death and to the past. The American West is full of dreams, towns and projects that have disappeared. Freeways, gas stations, motels, once situated on vibrant crossroads—now dead ends.

ON NEW FRONTIERS

You’ve always sought to discover places through the eyes of great artists throughout your work, like Ozu, Pina Bausch, and Buena Vista Social Club. Why do you have that urgency to document them? Why not keep their art to yourself?

I started working as a filmmaker in the late sixties and seventies. I felt there were still discoveries to be made, whether it was the American West or the Australian desert. There were places I could go that few others did. Portugal wasn’t even really part of Europe yet—it was a lost country looking over to the Indies. There were still…

Frontiers.

Yes, frontiers. But later, there seemed to be no more adventure territories left in the world. The only real adventurers were artists, and the frontiers were in their minds—how they saw the world and created new ones that had never existed before them.

When I saw Pina Bausch’s plays for the first time, I felt such a wealth of emotions that I found myself on the edge of my seat, weeping—I’d never wept like that in a movie. It was just pouring out of me. So I wanted to find out how she achieved that, with just a handful of people on stage and such sparse means. Before, you would need ten horses to drag me to see a ballet. And then suddenly, this ‘dance theatre’—as she called her new art form—was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. So, that need to share my discovery with others drove me to make a film about an artist for the first time. You could consider the movie on Ozu [Tokyo-Ga] a predecessor to that.

And Buena Vista Social Club came after.

Yes. I loved Cuban music, but I’d never been there, Havana was unknown territory. At some point before, I was made to listen to a crummy audio cassette by the music’s producer Ry Cooder. It was only a rough mix. But he said it was the most beautiful thing he’d ever made, which made me curious. I didn’t have a tape recorder in my home anymore, so I had to play it in my car and found myself driving through Los Angeles all night, just so I could keep listening. I told Cooder, “Where did you find these kids who make this electrifying music?” He laughed. “Well, they’re not exactly kids.”

The average age is, like, eighty-two.

Exactly. So Ry said: “Next time I go, you come with me!” And that’s what I did. It was an adventure to discover that culture, and the courage of these old men who still believed in their music, even if the world around them thought it was obsolete. Ry Cooder gave them the dignity they needed to make the entire world listen to their music, and I had the fortune to follow them on this journey, from shining shoes in Havana to being heroes on the stage of Carnegie Hall in New York.

You obviously have the travel gene within you. You left for Paris when you were young to be a painter, and you’ve always sought new settings. Where did this come from?

It came from the joyful realisation that the world was very different to my own. My parents had a German encyclopaedia from the thirties, where you could learn about every city and see pictures of faraway places. It wasn’t even contemporary; my father had inherited it from his father, and my favourite pastime was just to look at these pictures. An atlas of the world had also survived the war, and I loved studying those maps of foreign countries. I just stared at all the names, the cities, rivers and mountains. The first precious thing I owned was my globe. I would turn it around forever.

My parents didn’t travel much. They never had much of an urge for it. But the first real urgency of my life was to travel and to get ‘out there’ on my own.

Why was it so important to be alone?

When you are with other people, you see the world in a different way. Alone, you give all of yourself to the places you discover. The entirety of your very self is ‘there’. With someone else, your attention is largely with that person. It can be very nice to share such moments, but as a photographer, for instance, I must be bloody alone! Otherwise, it’ll be a different picture, because I need to abandon myself to a place in order to really be able to listen to it. Then, I can take my picture—as a recording of what the place has to tell.

Going back to the artists you have documented. Was there a shared commonality that you uncovered?

Each of them had their own approach. Anselm Kiefer stayed in Germany, for instance. I left. But he fought to find out the truth about the German past, of the time before he was born. He remained there in order to live the conflict with history and to confront people with the big lie they were living in post-war Germany. I didn’t want to. I preferred to discover something pure that wasn’t burdened with the past. What I love about his work is the fact that he stayed and that his journey was so different, even if our starting conditions were so similar, being born in the same year of 1945. And then, Anselm believes that whatever is out there in the world, from the tiniest atoms to the universe, to history, to poetry, religion or myth, you can turn it into painting. He’s so totally unafraid to confront anything, and make that a part of his painting process. I don’t know any other painter who thinks there is nothing that escapes his ability to paint it.

ON NEW GERMAN CINEMA

You admire him for staying in Germany, but you didn’t. It interests me to see that you are categorised under ‘New German Cinema’, with the likes of Herzog and Fassbinder. And yet what you were seeking was not German.

We started together from scratch and began a film industry in a country that did not want us. And indeed, there wasn’t really an industry left at all. We wanted to start something that didn’t exist yet at the time: an honest new language that allowed us to tell our own stories. We, the filmmakers of ‘New German Cinema’, were never a ‘movement’—we had nothing in common. Each of us has our own heroes and dreams, and that’s why we felt solidarity with one another. If we were anything, we were a movement of solidarity; completely impossible to imagine now, when the film industry is built on competition. We supported each other—even later founding a common production and distribution company, because no one else would distribute our movies in Germany.

[Pause] We really had nothing in common. I remember Fassbinder would call me up in the middle of the night and say: “Wim, I just got the projectionist at the old ‘Museum cinema’ here and he’s willing to stay two hours to show my work print. Come over!” So I would get out of bed to drive to the cinema. I remember that Volker Schlöndorff was already sitting there among other tired people. Rainer Werner had woken them all up, and he showed us the movie—which happened to be The Marriage of Maria Braun (1978). It was extraordinary. None of us would have been able to make it. And that’s why we stayed friends, because I knew I couldn’t make any of these movies Fassbinder was creating. Let alone Werner Herzog…what he was doing also seemed out of reach.

He also travelled a fair bit.

Yeah, but include me out. I don’t want to carry ships over the Andes. [like in Fitzcarraldo].

Again, it comes down to urgency. There was no German film industry. You had to create it.

Absolutely. There was an existential necessity to start a whole different film history in our country.

It had to be you?

Yeah. And why? Because I realised that people of my generation were doing the same thing, in England and America. The Kinks, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, they were all born in the early or mid-forties, like me, and they were revolutionising music. So listening to them, aware they were the same age, I believed I had the right to put the world of cinema upside down.

But not everyone was thinking that. There was clearly something unique about you and your contemporaries. I guess I’m trying to ask you whether you believe there’s an artist, who can make such cultural impacts, in everyone.

I very much believe in that. Every person is unique and has an inner-wealth, but only a few really tap into. If they only could…but a lot of people never discover that side to themselves. I mean Werner Herzog is one of these guys who really opened completely new horizons in the history of cinema. I remember when I was in film school. He was two years older and he showed us his first film, and he told us quite brutally: “You poor suckers! You’re wasting your time at film school. Go out there and start making movies instead! Here, look at my film—all it took was working hard to rent a camera.” His first documentary was tremendous, and he was (and remained) a real maverick. I always loved that non-conformist approach. I mean, obviously I went to film school—I didn’t learn much, but I attended. I really wanted to be a painter, and I learned more from painting about ‘seeing’ and image making than in film school. At the time, some of my favourite American artists, like Michael Snow and Andy Warhol, started to make movies, and I realised that this was maybe another way to approach painting… with cameras and on screen instead of a canvas. That suited me a lot, and I stayed hooked. You see, before, I couldn’t make up my mind: I loved writing, I loved music, I wanted to be an architect and a photographer—all of these things. But filmmaking was all of this rolled into one!

Do you think it is as simple to be a filmmaker now as it was then? Perhaps that sense of urgency has faded.

It’s different: both more simple and more difficult. There was more of a sense of discovery around the artform when I started. There were no film schools in Germany; mine was the first that opened and we were just twenty students. Now there are many, and there are thousands upon thousands of hopeful young filmmakers. Not all of them get to make movies. But then again…everyone can make a film today, using their computer and their smartphone. That’s a huge privilege, but at the same time, the world around them is so full of information and visual noise. That’s their stumbling block. There are too many distractions. They have a hard time even digesting what’s out there today, let alone what was there before them, the entire history of cinema. I was still thriving on that history.

Do you feel like the arts are slightly globalised in a sense? All over the world, we’re over-sharing the same information.

I wouldn’t want to grow up now, because I wouldn’t know what to do with all the information and the visual garbage. When I was eighteen, it was enough to buy one LP a week to be on top of things. In the seventies, I bought one a day, and then eventually, in the eighties, I found myself shopping twenty CDs at a time. I didn’t listen to most of them more than once. I’d be happy to find one that I would play with the same urgency as I did play my one weekly LP. So, I lived through that time in which we all were digesting more and more. Today, there’s simply too much overdosing of everything: books, movies, music, games, news. I would be scared and intimidated by the amount of consumption.

It was a privilege to become a filmmaker in the sixties and seventies. It was a wide open field. And I could make fictional films without a bloody script—I’ll tell you! Kings of the Road was done with a half page of story. Today: no way! I try to do a movie without a script, I won’t get it funded.

© 1994 Road Movies – Argos Films.

That’s surprising considering your reputation.

Neither me nor anyone else. “You better write a script, old man. We wanna find out if we like it before we give you any money.” The rules of the game have changed, and so have the expectations. If you need money to make a movie, then play to the rules and show up with a script. And a storyboard. Basically, the film is done before the first day of shooting. All you need is to execute it. Only if you don’t need much money, can you define your own rules. I’ve made several movies without scripts and they were among my best work. I could still do it. But it’s hard to prove it [laughs].

ON GOD AND LEGACIES

How spiritual are you?

I am a spiritual person. I believe in a bigger intelligence than our own, and a bigger spiritual essence than our own. You can catch glimpses of it through meditation, prayer or other spiritual habits. But organized religion? Well, it can be both an eye-opener and a trap. I respect those religions that make you ‘see’ and ‘respect’, both others as well as other beliefs. I am deeply disturbed by all aspects of religion that prohibit—which has unfortunately increased in the Christian, Jewish and Muslim world. A lot of these militant or ultra-orthodox forces in all religions want to silence other people and want their followers blind, not open-eyed.

It’s curious that you called the Pope an ‘artist’ after your documentary on him.

Yeah, he [Pope Francis] was a visionary. Simply choosing for the first time the name of this rebel and reformer of the church, Saint Francis, was already a visionary act. I believe in God, even if I don’t quite know what to call him, and even if I don’t subscribe to one way to approach him. I firmly believe there is a benevolent God who sees us. He’s certainly a little disturbed right now by how mankind is behaving…

The way the world is going, it would seem like we’re failing him.

We’re totally fucking it up. But what’s he, or she, to do? I guess we were given that freedom. He must be thinking in other terms than our human history. That history repeats itself in malicious ways. The human race seems incapable of learning from it, and that deeply disturbs me—especially as a German. I always took it for granted that people could and would learn from the past. The Germany I grew up in was peaceful, looking to Europe as a bigger entity than their own ‘nation’. The German people in the seventies, eighties, and nineties had learned from history, I believe. But even they’ve forgotten their lessons today. There’s new nationalism, racism…and all these other damn -isms are showing their ugly heads here as much as in America, Russia, or China.

Maybe that’s one of the reasons why I believe in movies so much, because they have the power to remind us of our past. As a filmmaker you can re-establish some simple, obvious truth about the world.

Do you believe in leaving behind a legacy?

No, not in the way that word is used. I don’t care about a ‘personal legacy’. But preserving the work is an obligation; especially because films are their very own entities. You see, I basically produced all my films myself, and I felt like a parent towards them. Then, in the late nineties, I lost them all. A long and sad story. I was miserable, as ‘my children’ were on their own for twelve years. I watched them get distributed and exploited around the world continuously, but nobody really took care of them. So, the films deteriorated.

The digital age came, and these films needed to be preserved. Everything that only existed in the old analogue celluloid world was condemned to die. Eventually, luckily, I was given the chance to buy them all back. It was a huge investment, but I actually didn’t even want to own them myself anymore. Such ownership of work, as I had experienced painfully, sucks. Movies are their own characters and establish their own relationship to the world. They live and exist only because people see them, love them, and are nourished by them. Movies have a right to their own life, I realized. They should be able to take care of themselves! That would ensure their future in the best way. The ideal form for that to happen would be a foundation. That would be so much better than all other ownership. They would own themselves! So we founded the non-profit Wim Wenders Foundation that collected the funds to buy all fifty-five films back. All the money they make goes back into their own preservation. Twenty-one of them have already been restored to glorious 4K, in the best possible way. They are already self-sufficient, the others are following. These films will survive me as well, and that makes me happy. They’ve become these free entities now, and when I see them again, I’m amazed sometimes. They’ve grown up, from me as well.

The archives throughout your career are well-preserved, from photographs to cinema and your books. It seems ripe for a filmmaker to follow your journey in the same way you have with Pina Bausch and Anselm Kiefer. What do you think they would uncover about you?

There was one made a few years ago named Desperado, which centred largely around the beginning of my work up to Paris, Texas. I think what needs to be seen is the work and not the person. I’ve never been interested in biographies, and even if I make a movie about an artist, it isn’t about their lives. That should remain private. Their work matters. In Pina, you don’t learn much about her life, but you understand the enormous emotional importance of her work. In Anselm, you realise the scope and beauty of his art, and the wealth of things he’s investigating. And I think I did this also with Salt of the Earth, my film on Brazilian photographer Sebastiao Salgado. The work is what remains. Not the people. I’m not going to be here forever, but the work will remain for a while. It will be a mirror of the six or seven decades I witnessed with these films. I think it’s worth persisting with, because someone might learn something from my films in another fifty years, just as I did with the history of cinema—from filmmakers who were long dead even when I grew up. I became a richer person through knowing these movies. I truly believe that films are entities of their own, just like books: Huckleberry Finn doesn’t belong to Mark Twain; he belongs to me. Among many others.

I believe everyone—yes, you too—are the co-owners of my cinema.

Harry Dean Stanton and Dean Stockwell.