Director and former documentarian Maura Delpero discusses her second feature film Vermiglio, a contemplative family saga set in a mountainous Italian village.

Vermiglio is a small village located in the Vai di Sole, a valley in the province of Trento in northern Italy. The vertiginous location is the eponymous setting for Vermiglio, Italian director Maura Delpero’s second feature film about a large family, whose father is the schoolmaster, during a fateful year: Winter 1944 to Autumn 1945.

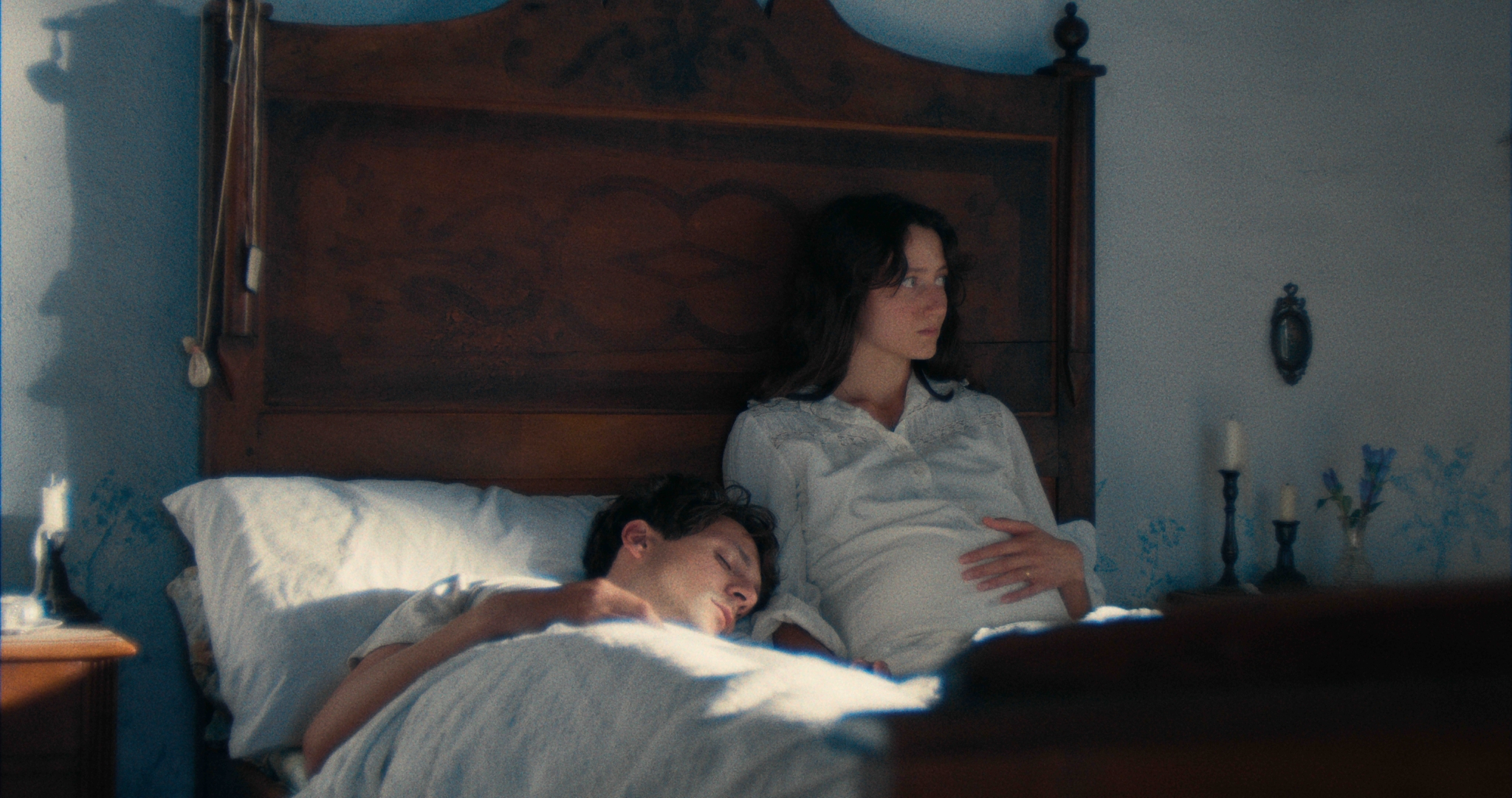

The character we first meet is a collective one—the family sleeps in unison, at school the children do their morning stretches in tandem and pray together, the congregation of the village swarms around after mass. Yet the story soon individuates. A fish out of water, Pietro—his olive skin illuminated in the snow—is a deserter from the war who arrives in the village. Lucia, the eldest daughter, takes a startled shining to him, and they begin a wordless, snatched romance, before Pietro asks her father’s permission to marry her in his literacy class for grown-ups. Whilst this love story serves as a useful logline, Delpero treats each of her characters’ psychodramas with due attention. Ada, is a sexually confused teenager who punishes herself for ‘praying’ behind the wardrobe, Flavia, a clever people-pleaser has hopes of going away for school, and the brawny eldest boy, Dino, struggles to match his father’s high expectations. Even the upstanding patriarch has his own private vices and vexations.

Vermiglio is punctured with moments of bruising beauty—the cabbage leaves desperately wrapped over a sick infant’s head, love letters surreptitiously exchanged, the candlelit feast of Saint Lucia sonically illuminated with carols (actual recordings of Vermiglio’s villagers). Delpero has a background in documentary and Vermiglio—which largely uses non-professional actors—is suffused with a sense of ethnography, of a real place and way of life. However, based on the director’s own family history—the titular village was the home of her grandfather, a profound sense nostalgia and tenderness also seep through, like limbs warming up after coming in from the cold.

At the Charlotte Street Hotel in December, beside a roaring fireplace, A Rabbit’s Foot talked to Delpero about Neorealism, Natalia Ginzburg and the powerful sound of silence.

KG: Vermiglio is a real place, and maps are an important motif in the film. How did you find this place?

MD: It’s nice that you talk about maps—the atlas that is in the house. We really talked about this object a lot, because we are talking about an isolated place in time and space. The idea was that the world outside was so far away—the fruit of imagination. I like that there’s this atlas in the father’s room and everyone is secretly dreaming through it—Flavia is dreaming about culture, and Ada is regretting Virginia going away and Lucia is waiting for her lover. I remember my generation still had this space for imagining and dreaming and not knowing. I used to dream a lot through atlases. I like the fact there is this little house up in the mountains dreaming about the world. Especially during the war they were really isolated. Everything becomes great, like cinema.

For me this village is also a place of my soul, because it’s where my father was born. It’s a place from my childhood, and maybe I kept this dreamy, fantasy atmosphere of childhood where you look at things with big eyes. When I started to write, I realized I had a lot of material–a lot of souvenirs—do you say souvenirs?

KG: Memories. Or a souvenir is a physical object.

MD: A lot of memories from images, from stories, and everything came from this moment where you are a child and you absorb things without filters. So they really stay in you in a sensorial way. I remember the smell of the hot milk in that freezing weather, and the smell of my grandmother’s kitchen. Even if cinema is limited—you can’t have the five senses—I tried to put those five senses in there.

KG: It’s funny you say that, because one of my earliest memories is of milking a cow at nursery school, and obviously that is the opening image of the film. I found it really haptic.

MD: To me it was important to begin like this to set the scene as a world of necessity. That milk is the milk they are feeding their children to go out against the cold. You’re in a difficult world, really, you can die from cold, you can die of hunger, your babies will probably die of illness. So it’s really a necessity. And in the relationship with animals as with all the nature, it’s a really dependent relation. That’s why I didn’t choose a professional actress from Rome. Lucia [Martina Scrinzi] lives in that region, she has animals, she has this relationship with the world.

KG: Can you expand on the casting and the balance of professional and non-professional actors? So Lucia was someone you just found?

MD: She wrote us an email, because a lot of them—we went to find them, because they were people who would never have showed up to a casting. You know, all the faces of the old men, I went to bars looking for them. And the doctor, the priest, all these people. And the children and teenagers, of course. But Martina, she wanted to be an actress, but she had only had dance and theatre and she wrote us an email with a video, and we were like, ah ok, this is something else.

KG: I suppose it makes sense for her character, who clearly wants something more, wants glamour—when she talks about the white dresses of the ladies in Sicily.

MD: I think that sentence about the white dress has to do with our tendency as women to always feel too ugly. This weakness, this sense of ‘I’m not enough,’ I’m not enough for him. I’m so in love with him but I’m not enough for him.

KG: You referenced the necessity and endurance of living. In those early scenes you start also with this communal body, but then you follow these individual stories. How did you find the balance between the individual and the collective?

MD: This is one of the biggest themes of the film. We are in a transitional world. It begins with a full bed and ends with an empty bed. We see the passage from village to city, community to the individual. Lucia, she begins as a country girl and she ends up as a modern woman that says goodbye to her baby to go to work alone. Everyone is more free and more alone.

And in terms of casting, I was not just casting the single character, I was casting the relationship, both physiognomically and in terms of energy and relationship I had to build. When I know this is the challenge I cast a long time before, so when they arrive on set they really know each other. Those beds were their beds. They’d already been fighting, they already loved each other. Dino—the older brother—was already their myth, he had the little one on his shoulders for weeks.

KG: Can you talk about Ada’s character, she probably has the most daunting role.

MD: It was very difficult to find an actress for that role because we were looking for a 14 to 15 year-old girl. And contemporary 14 or 15 year old girls are completely different. And then I had this idea of going to the rural high school where you go when you want to become a farmer. Two people came out from that casting—Ada and Dino. He’s 14 or 15, but if you look at Dino’s hands they’ve already worked. They’ve touched cows. He used to accompany 600 sheep from one part of the valley to the other, you know? He’s not a boy that touches iPhones. When I interviewed for Ada, I asked the same question to everyone. One of the questions was what was your happiest moment in life so far. Everyone was like ‘oh when I went on TikTok and…’ And Raquel—Ada—she told me in a very serious way—when one of my chickens recognized me and ran towards me.

KG: Vermiglio is set in 1944, in the decade when Neorealism was emerging in Italy—was that an influence for you?

MD: Of course. Coming from documentary, I have a strong reality parameter. So when I do fiction inspired by reality, I need to begin from the ground, from reality, from the roots. The preparation is really long, I try to find things that are already there, objects that are there, people that are there, dialect that comes from there, costumes. I pick from the world and then structure it in a fictional way. It’s a difficult decision because you lose a lot of opportunities in terms of commercializing. So when I decide to stay so radical, I also have to do the film with less money, which means less time. It’s a lot of suffering for me. But it’s good not to compromise. I think when you watch it you say, okay, this is something authentic.

KG: Can you talk about the use of sound? It’s a very quiet film in a literal, and metaphorical sense, and it’s interspersed of course by the beautiful Chopin music.

MD: I think we experience it as a silent film because we are used to a lot of sound. The film asks for silence and offers the viewer the possibility to enter another space and time tunnel. You have to do it in a theatre, not in your home watching your phone and going to the fridge. If you enter this bubble, you will hear a lot of sound. Silence has a sound—we use a lot of direct sounds from inside and outside the house. And the music of the dialect itself. There’s a specific way people talk. And the fact they talk very little. In this space [the mountains] people don’t talk a lot. Their tongue will be freezing. Other parts of Italy are more talkative. Here they are very reserved, emotionally reserved. For the music, I didn’t want a soundtrack, so all the music is internal, all diegetic. The Chopin, even if it is anticipated in the scene before, they always come from a source within a film. The songs are sung by people in the town—the same people you see in the bar, with those faces, they are the singers.

KG: You mentioned your father earlier. Were there any personal links to the character you shaped? What did you want to say about him?

MD: He’s based on my grandfather. My father inspired little Pietrino—the one who asks questions. At the time the school teacher was an important person. Like the priest or the mayor. They were the three people who had authority. My grandfather came from the rural tradition but at the same time had studied so he was this kind of intellectual peasant. He was intellectually curious. He didn’t hit on hands like other teachers. But at the same time he was a patriarch. His relationship with the mother is old fashioned, but at the same time you see them in bed at night—when you see the truth, the couple in bed. They are much more equal. He confesses his love, worries about Pietro’s letter. He’s the eleventh child.

We are in a transitional world. It begins with a full bed and ends with an empty bed. We see the passage from village to city, community to the individual. Lucia, she begins as a country girl and she ends up as a modern woman that says goodbye to her baby to go to work alone. Everyone is more free and more alone.

Maura Delpero

KG: On the epistolary form… ‘epistolare’ is a word the children are taught at school and characters are often shown revealing themselves in writing. I was reminded of Natalia Ginzburg while watching this—with the tragicomedy, as well as the wartime setting. And I was wondering if there were any literary influences here?

MD: I come from literature, not cinema, and I think you can feel it. I love Natalia. Because I love the fact that she can tell the little things of day-to-day life that tell you about big life. There weren’t direct influences but there was this sensation from the beginning that it should be like a family novel, where you follow the destiny of different people, but they are also a unity, with a multi-generational script, even if it’s more difficult. It was important not to choose one point of view.

KG: The sense of time passing also adds to the sense of it as a novel.

MD: It was decided to structure it as four seasons, and to have these big elliptical passages that push the story forward and create a sense of a year. At this epoch the season was an important time parameter. The whole time frame is one year, from winter 1944 to autumn 1945. You begin with Winter, then you have this moment in which Spring arrives with pollen, the people arriving. There are bridges–of Summer, and of the Autumn, when just three children go to school instead of the whole family. It’s four seasons. But you hear that, no? Vivaldi’s Four Seasons.

Vermiglio is in UK cinemas from 17th January