The legendary cult filmmaker talks his film Shadow of Fire and the resurgence of interest in body horror.

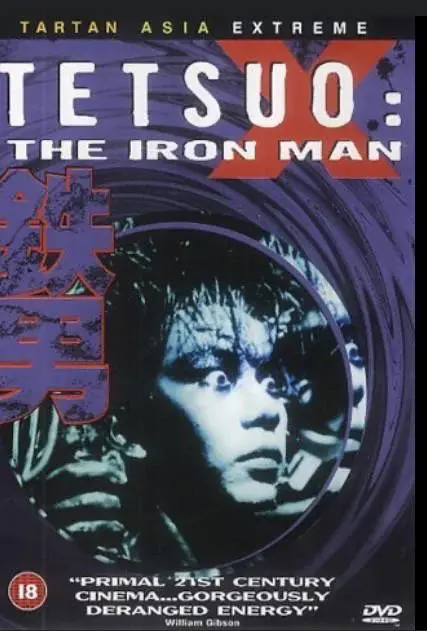

One of Japanese cinema’s most fiercely independent voices, Shinya Tsukamoto is the writer-director behind such electrifying cult films as Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), Tokyo Fist (1995), A Snake of June (2002) and Vital (2004): transgressive tales of psychological repression and transformation of the flesh. Alongside David Cronenberg, he’s considered one of the godfathers of visceral body-horror cinema (plus cyberpunk movies), though he’s also made plenty of more cerebral gems. And as an actor, he’s worked with the likes of Martin Scorsese (Silence, 2016) and Takashi Miike (Ichi the Killer, 2001).

A SNAKE OF JUNE (DIR. SHINYA TSUKAMOTO, 2002)

Tsukamoto’s more recent work has focused on how war transforms and scars people just trying to survive. His latest, Shadow of Fire (2023), concludes what’s been described as Tsukamoto’s anti-war trilogy – preceded by soldier tale Fires on the Plain (2014) and late Edo period drama Killing (2018). Set just after World War II, Shadow of Fire tracks the struggles of ordinary people in an unnamed Japanese town that’s in thrall to the post-war black market; in particular, a young widow (Shuri) who’s become a sex worker, and the orphaned boy (Oga Tsukao) who enters her life.

A RABBIT’S FOOT caught up with Tsukamoto to discuss anti-war cinema, body horror’s recent ‘prestige’ success, the Tartan Asia Extreme era, and Super Furry Animals.

Josh Slater-Williams: How were the first seeds of Shadow of Fire planted?

Shinya Tsukamoto: Shadow of Fire is set in the immediate [aftermath] of World War II. I don’t actually disclose anything specific about the location, but there was a big black market in Ueno around that time that was on my mind. They were illegal markets, but loads of people gathered around these places all over Japan, trying to live their lives. Ten years ago, when I made a film called Fires on the Plain, at that time I was thinking about society in Japan and how it felt like war was looming towards it [again]. I was so worried and thought now is the time to make these kinds of films. There are people who are still alive in Japan who remember World War II and the atrocities of the war. But they are vanishing from the world. While they are still alive, I thought I really needed to make films to convey an anti-war spirit that’s not [prominent] in Japan.

JSW: Can you explain the choice of title?

ST: ‘Hokage’ is what Shadow of Fire is called in Japanese. The direct meaning is ‘flicker of light’. There are flames everywhere, generated by war. I wanted to depict the ordinary people living day to day under the shadow of those flames.

A STILL FROM SHADOW OF FIRE (DIR. SHINYA TSUKAMOTO)

JSW: There are some allusions to this being set just after that war, but how the costuming and locations are presented lends this air that the film could also plausibly be set in many periods.

ST: This is set post-World War II, but I really wanted audiences to feel that war is imminent for everyone, wherever you are. I wanted the feeling that those kinds of war [experiences] are always looming. Nothing is overly explained, including names. I named characters A Man, A Woman, A Kid, that kind of thing. That’s my intention to be abstract, as the message to convey is that it can happen everywhere, anywhere.

A STILL FROM SHADOW OF FIRE (DIR. SHINYA TSUKAMOTO)

A STILL FROM SHADOW OF FIRE (DIR. SHINYA TSUKAMOTO)

JSW: You’re usually part of the cast of your own films. Why did you abstain from an onscreen appearance this time?

ST: Normally, I have got a strong character that I really want to play myself, so that’s why I am [almost] always in my films. Whether or not people want me to be in it, I always want to be in it. But this time, there were no characters that I thought I needed to play. What I did was I just focused on being a director, as well as a cinematographer.

JSW: When British distributor Tartan Films released some of your earlier features on DVD in the 2000s, they were put under the label Tartan Asia Extreme, alongside works by wildly different directors like Takashi Miike, Park Chan-wook and Johnnie To. When I was a teenager then, I found this label’s marketing very exciting as my introduction to live-action East Asian cinema. But as an adult, it seems like grouping those filmmakers in such a superficial way was reductive and not necessarily fair to the artists involved. If this Asia Extremelabel is something you were aware of, what did you make of it?

ST: You said it perfectly. I’m glad you thought that was a silly grouping. Hearing that from you now makes me really happy. I knew they were releasing my work as ‘Asia Extreme’ and I can’t blame them, in a way. I do understand that it’s Asian, it’s extreme, and putting them together is an easier sell. I kind of understand it. But at the same time, I also don’t understand why [the whole imprint] was called Asia Extreme, because those other people are quite different categories of directors. Maybe it was an easier way for English speakers to understand Asian cinema. So in a way, it’s like, c’est la vie.

JSW: In recent years, body horror movies have been garnering uncharacteristic levels of ‘prestige’ in terms of big festival awards and mainstream crossover; most notably, Titane (2021), which won the Palme d’Or and was France’s official submission for the Oscars. And then this year, The Substance (2024) won the Best Screenplay award at Cannes. Why do you think these subjects are having such ‘prestige’ success right now?

ST: The Substance hasn’t been released in Japan yet. Is that actually body horror? I really want to see that now. With regards to Titane, it’s understandable why it got the mainstream attention and awards. It’s because of the content. The way they show body horror was a little bit more cinematic. When you’re talking about science fiction or body horror, it doesn’t have to be splatter. You can delve more into the emotional horror of people, which Titane did really well. I was taken aback when the film won the Palme d’Or in 2021, but as long as it is well made, then why not? The quality of the film is there. I’ve been moving away from body horror for a long time, so maybe I’m distanced enough from the genre to feel like this.

JSW: Are you aware of a Welsh band called Super Furry Animals who referenced Tetsuo II: Body Hammer (1992) in one of their songs?

ST: What’s the title of the song?

JSW: (Drawing) Rings Around the World, from 2001.

ST: I’ve never heard of the song nor the band. In what sense do they use Tetsuo II?

JSW: I believe that the song is about the fusion of technology and human emotion, so the Tetsuo reference seems affectionate. When the singer sings that “Tetsuo II became me and you” in one verse, it’s like he’s saying that we’ll all end up merging with technology and machinery if we’re not careful. And then the next lyric describes potentially dangerous human connection as “body hammer blows”. Elsewhere in the song, other body-horror imagery (“Sooner or later we will melt together”) is reminiscent of the Tetsuo films.

ST: Oh wow! I’m glad that they remembered Tetsuo II for so long as the song was made [a decade] after Tetsuo II was made. I feel honoured that I somehow inspired this UK rock band to use Tetsuo as the reference.